Temperature rise ‘unprecedented in the instrumental record’

June 5, 2024

1.3°C jump in 2023; emissions budget shrinking fast

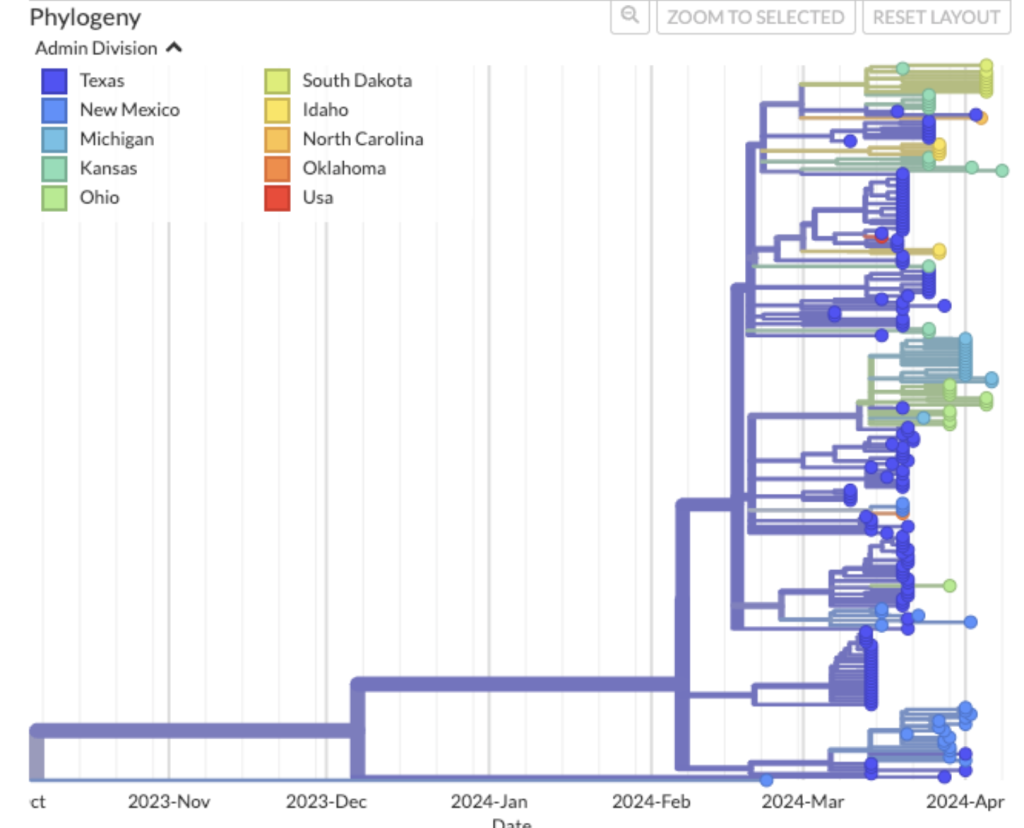

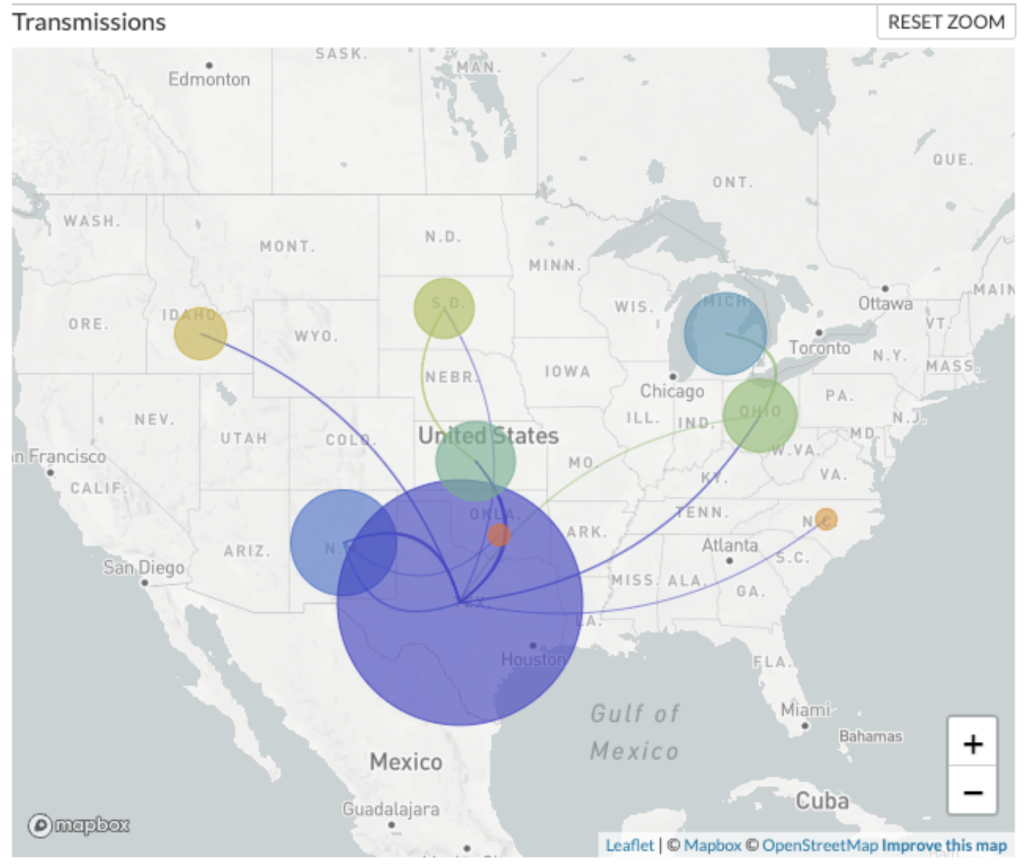

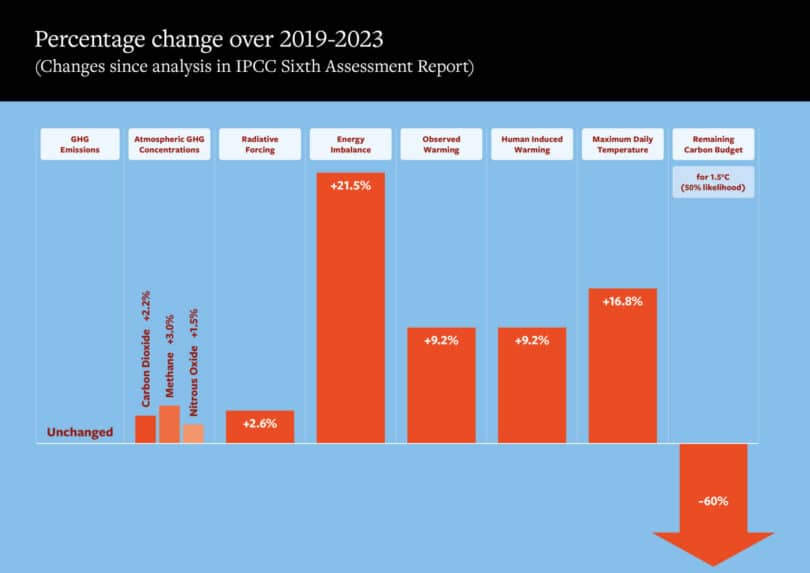

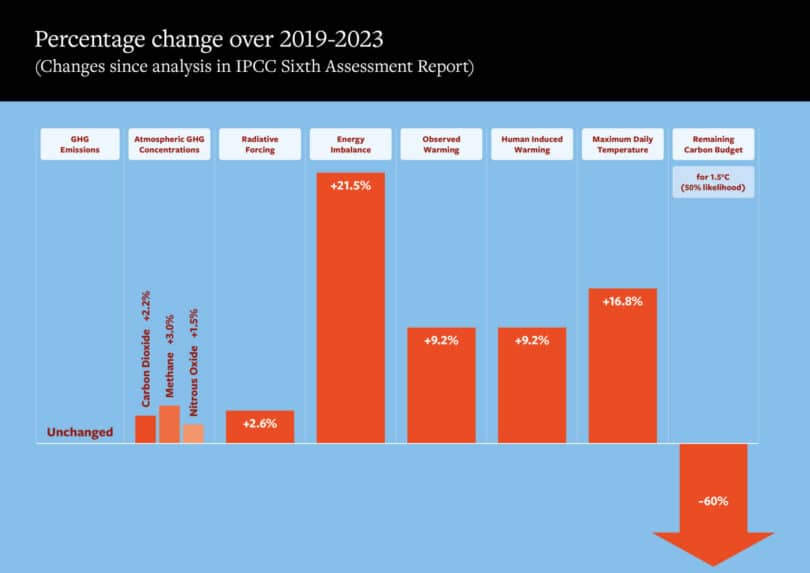

The second annual Indicators of Global Climate Change report, which is led by the University of Leeds, reveals that human-induced warming has risen to 1.19 °C over the past decade (2014-2023) — an increase from the 1.14 °C seen in 2013-2022 (set out in last year’s report).

Looking at 2023 in isolation, warming caused by human activity reached 1.3 °C. This is lower than the total amount of warming we experienced in 2023 (1.43 °C), indicating that natural climate variability, in particular El Niño, also played a role in 2023’s record temperatures.

The analysis also shows that the remaining carbon budget — how much carbon dioxide can be emitted before committing us to 1.5 °C of global warming — is only around 200 gigatons (billion tons), around five years’ worth of current emissions.

In 2020, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) calculated that the remaining carbon budget for 1.5 °C was in the 300–900 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide range, with a central estimate of 500. Since then, CO2 emissions and global warming have continued. At the start of 2024, the remaining carbon budget for 1.5 °C stood at 100 to 450 gigatons, with a central estimate of 200.

Project coordinator Piers Forster of the Priestley Centre for Climate Futures said:

“Our analysis shows that the level of global warming caused by human action has continued to increase over the past year, even though climate action has slowed the rise in greenhouse gas emissions. Global temperatures are still heading in the wrong direction and faster than ever before. Our analysis is designed to track the long-term trends caused by human activities. Observed temperatures are a product of this long-term trend modulated by shorter-term natural variations. Last year, when observed temperature records were broken, these natural factors were temporarily adding around 10% to the long-term warming.”

The authoritative source of scientific information on the state of the climate is the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), but as its next major assessment will not happen until around 2027, this creates an “information gap,” particularly when climate indicators are changing rapidly. The new report is accompanied by an open data, open science platform — the Climate Change Tracker’s Indicators of Global Climate Change dashboard, which provides easy access to updated information on the key climate indicators.

Other key findings

Human-induced warming has risen to 1.19 °C over the past decade (2014-2023) — an increase from the 1.14 °C seen in 2013-2022 (set out in last year’s report).

Human-induced warming has been increasing at a rate that is unprecedented in the instrumental record, reaching roughly 0.26 °C per decade over 2014-2023.

This high rate of warming is caused by a combination of greenhouse gas emissions being consistently high, equivalent to 53 billion tons of CO2 per year, as well as ongoing improvements in air quality, which are reducing the strength of human-caused cooling from particles in the atmosphere.

Graph from Carbon Brief summarizes percentage changes in global climate change indicators between 2019 and 2023. Data from Indicators of Global Climate Change.

https://climateandcapitalism.com/2024/0 ... al-record/

******

When It Comes to the Environment, There Really Is No Such Thing as a “Good” Car

Posted on June 7, 2024 by Yves Smith

Yves here. We’re doubling up on environment-related posts today to make up for having neglected this area a bit of late. This offering crystalizes an issue I have not articulated myself, and I realize also contributes to my annoyance with electric cars as climate change hopium. We need far more radical reductions in energy and materials use to have any hope of escaping worst outcome that pretty much all Green New Deal schemes contemplate. The Green New Deal is at its core, “Let’s use techno-fixes, better shopping, and some mild activity dis-incentives to allow us to preserve the way we do business now.”

Aside from the near-necessity of cars for dispersed single family homes, another climate-costly addiction, the auto industry is a massive source of economic activity, both directly and through procurement and sales networks (and in the US, financing!). As proof, look at how the US is fighting tooth and nail to prevent the entry of cheap Chinese EVs, which would eat considerably into the sale of US EVs and conventional cars. It’s too late now, but if we had more lead time, imagine the economic displacement caused by a serious and well funded effort to improve public transportation (even with that more forceful measure not being adequate either). Horrors!

Opening comment by Bill Haskell at Angry Bear. Original text by Emily Atkin and published at Heated

Contrasting EVs to gas powered vehicles. And will EVs be as bad or worst that gasoline powered vehicles. And some promoters of EVs go in the opposite direction over promoting EVs or what the article calls green washing EVS.

~~~~~~~~

Financially motivated EV misinformation comes from both sides of the aisle (the lane?). Industries that see EVs as a threat exaggerate their harms in a bid to get you to hate EVs. And industries profiting from EVs greenwash their benefits in a bid to get you to love EVs.

Most often, you can recognize EV misinformation by its attempts to promote black and white thinking. It’ll either be “Electric cars are bad and gas cars are good” or “Electric cars are good and gas cars are bad.”

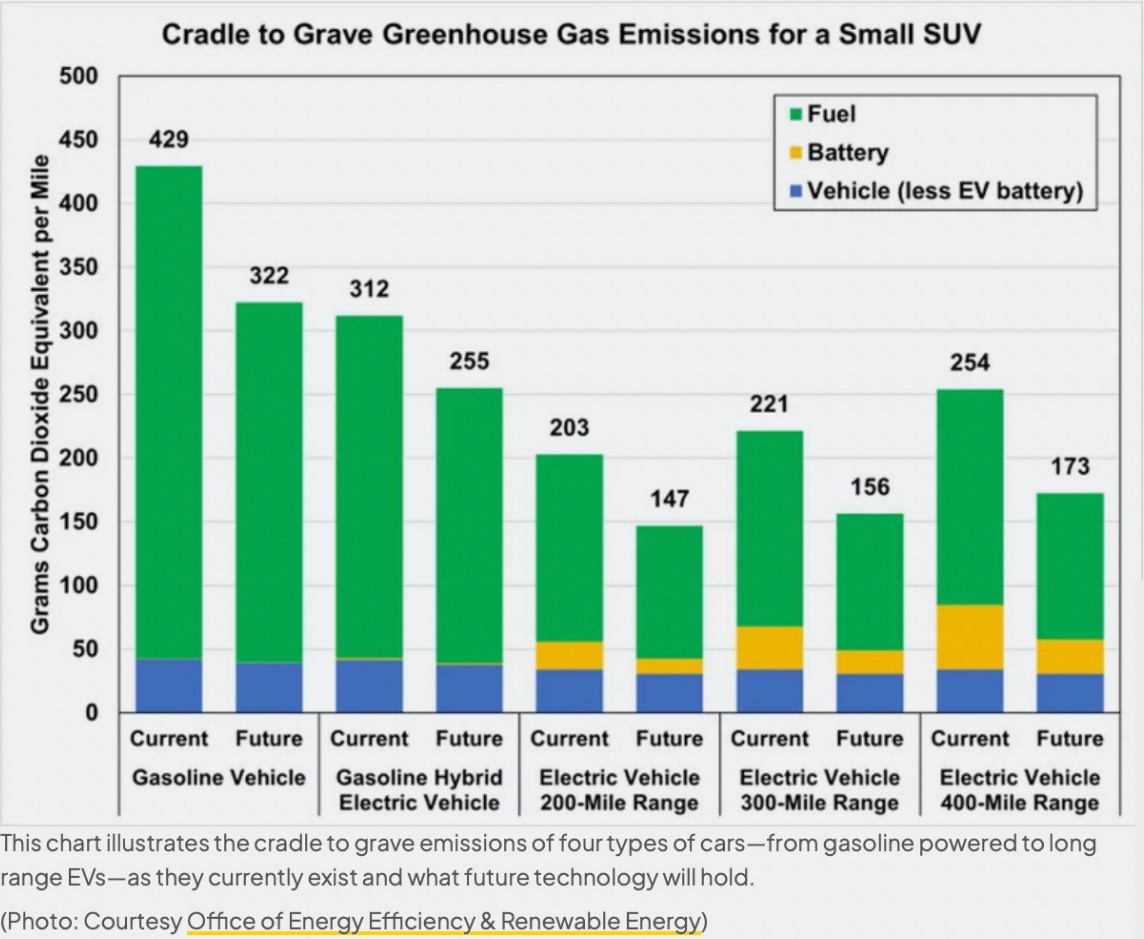

But the truth is, when it comes to the environment, there really is no such thing as a “good” car. The real question is: how bad are these cars in relation to one another? This is where most EV misinformation lies.

Misleading: It’s more environmentally harmful to make an EV than a gas car.

This statement, by itself, is technically true. ”To run, EVs require six times the mineral input, by weight, of conventional vehicles, excluding steel and aluminum,” the Washington Post reported in 2023.

That’s because each EV has a 900-pound battery block containing roughly 353 pounds of crucial materials or metals including cobalt, nickel, lithium, manganese, aluminum and copper. Gas cars don’t have that, so it’s less emissions-intensive to create a gas car than an electric car.

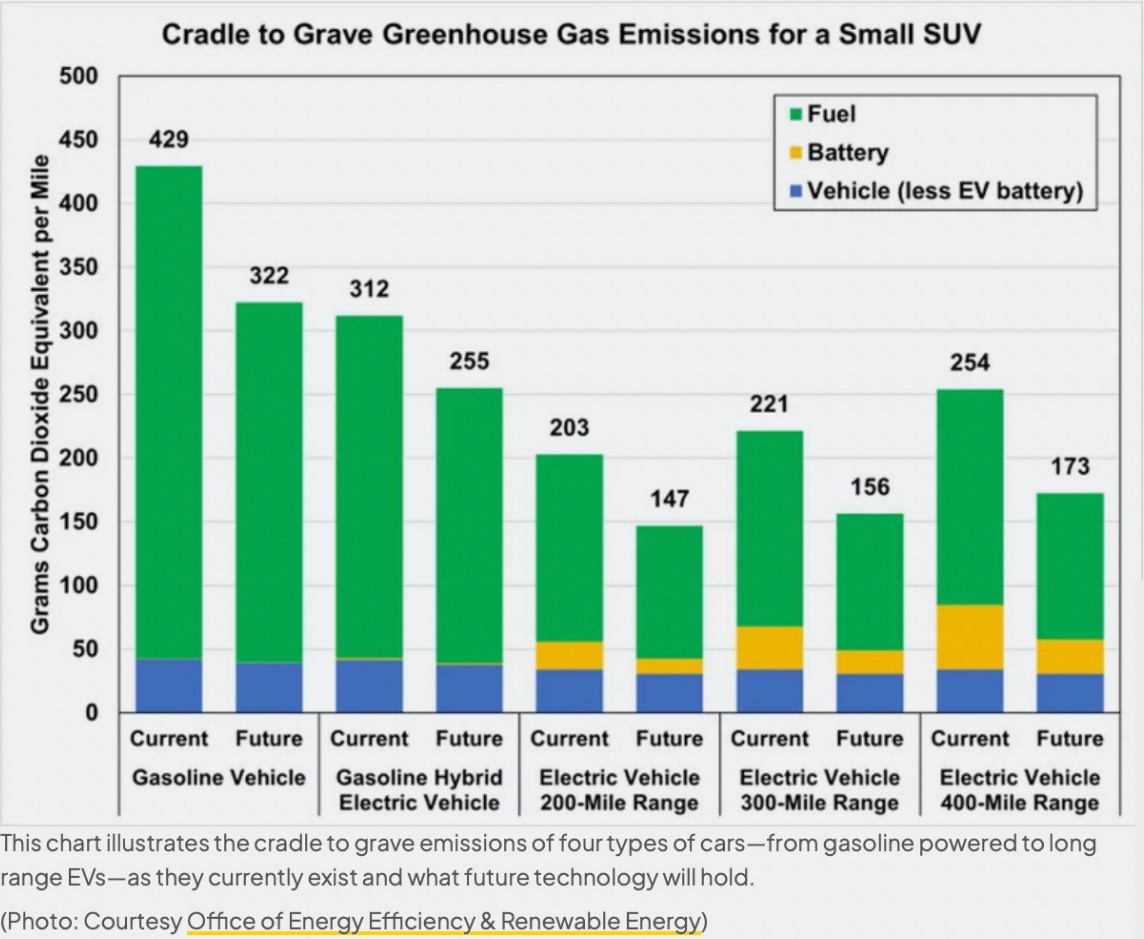

What’s misleading about the statement is not the statement itself, but the context in which gas car proponents say it. Usually, they’re saying it to convince you that electric cars are way worse than gas cars for the environment. And that’s just frankly illogical, because the vast majority of pollution that comes from cars does not come from making the car. It comes from driving the car.

If you’re only buying a car to simply look at it and never drive it, then absolutely, it would be way more environmentally-friendly to buy a gas-powered car.

But if you do, in fact, intend to actually drive the car you buy, then an EV is going to be the less environmentally harmful choice—even if coal is part of your local electricity mix.

That’s not according to me, either. That’s according to a peer-reviewed study funded by the Ford Motor Company, a company that makes most of its profits from gas-powered vehicles.

That study, conducted by the University of Michigan, found that EVs become less emissions-intensive than gas cars after “1.4 to 1.5 years for sedans, 1.6 to 1.9 years for S.U.V.s and about 1.6 years for pickup trucks, based on the average number of vehicle miles traveled in the United States.”

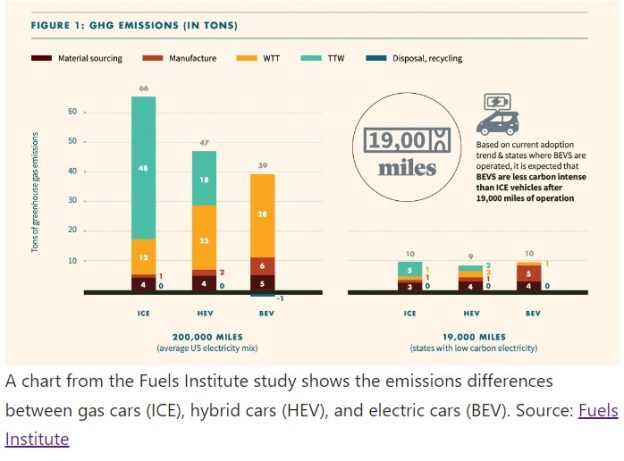

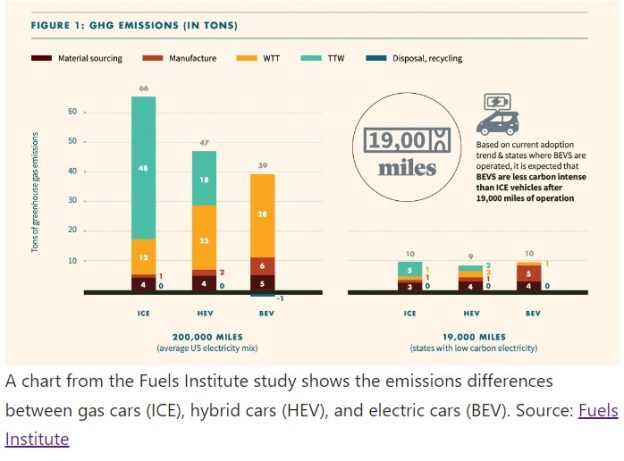

Another study, conducted by Ricardo PLC for the nonprofit Fuels Institute, similarly found that driving a gas car is far worse for the planet than EVs, even when coal is part of the electricity mix.

Over 200,000 miles of driving, it found, a gas car emits 66 tons of greenhouse gas emissions, while an EV using the current average U.S. electricity mix emits 39 tons. In states that already have low-carbon electricity, an EV becomes less emissions-intensive than a gas car within 19,000 miles.

As time goes on, experts expect that it will take less and less driving time for EVs to become cleaner than gas cars. That’s not only because the electricity mix is expected to become cleaner; but also because the majority of battery materials used to make the cars are likely to be recycled.

Recycling and reusing the minerals used to make EV batteries “will drastically cut down the amount of wasted material compared with fossil fuels which disappear invisibly but harmfully to heat the planet,” the Guardian noted in December. The story cited data that suggests that “after recycling, battery material waste over an electric car’s life will be about the size of a football, or 30kg, by 2030.”

Of course, we all know how trustworthy corporations have been about recycling. But the point stands: anyone who says the creation of EVs makes them environmentally worse than gas-powered vehicles is either misinformed or trying to mislead you.

Myth: Because gas-powered cars are worse for the environment, we don’t need to worry about the harms of EVs.

Gas-powered cars are worse for the environment than EVs. But this does not mean EVs are good for the environment. Anyone telling you that is either misinformed or trying to mislead you.

In a recent investigation of this same debate, the Guardian found that gas vehicles were worse for the planet than electric vehicles. But it also ended on this important note: “the green credentials of electric cars [do not] absolve the buyers of battery minerals of responsibility for abuses in the supply chain.”

As Washington Post climate advice columnist Michael J. Coren wrote last year:

Mining minerals is never a clean affair. Cobalt from Congo, lithium and graphite from China, nickel from Indonesia and Russia, and battery supply chains that run through Xinjiang, in the Uyghur region where forced labor has been rampant: All of these have immediate problems, which The Washington Post explored in our “Clean Cars, Hidden Toll” series. Guinea, home to the world’s largest bauxite reserves for aluminum, yields misery for local communities. Nickel refiners in Indonesia are adopting a risky technology. Mineworkers in South Africa, the world’s largest producer of manganese, face neurological ills.

“The transition to low-carbon fuels is not a magic bullet with no negative outcome,” Sergey Paltsev, a senior research scientist at MIT, told Cohen. “There is no free lunch. But it’s much less harmful than if we stay with fossil fuels. That’s the conclusion.”

Misleading: The U.S. electric grid can’t handle widespread EV adoption.

HEATED reader Oscar asked us to research the widespread claim that a large increase in electric vehicle adoption would place massive stress on the U.S. electric grid.

Oscar also wanted to know how much current U.S. infrastructure would need to be updated to accommodate a massive increase in EV adoption.

For a really detailed answer to both questions, I recommend reading this 2022 article in Scientific American, “Why Electric Vehicles Won’t Break the Grid.” But if you don’t have time, here’s the gist in one quote:

“We can’t just sit back and say, ‘OK, the grid can handle it; it’ll take care of itself,’” Baldwin added. “It will take attention, and it will take some adjustments to how things have been done in the past, but all in all, I’m optimistic that this is something that we can do.”

A big conclusion I took from the article is how much gas car proponents are exaggerating the strain on the grid from EVs:

In California—the national leader in electric cars with more than 1 million plug-in vehicles—EV charging currently accounts for less than 1 percent of the grid’s total load during peak hours. In 2030, when the number of EVs in California is expected to surpass 5 million, charging is projected to account for less than 5 percent of that load, said Buckley, who described it as a “small amount” of added demand.

But as people continue to buy EVs—and they are, across the world—it’s true that utilities will need to make adjustments to accommodate increases in demand. But experts say it’s not the huge deal gas car proponents are making it out to be.

“We’re talking about a pretty gradual transition over the course of the next few decades,” said Ryan Gallentine, transportation policy director at Advanced Energy Economy. “It’s well within the utilities’ ability to add that kind of capacity.” …

That success will hinge on utilities being proactive in planning for millions of additional EVs on the roads in the coming decades. It will also take some adjustments, experts said. EV owners and utilities must take advantage of up-and-coming charging technologies that will save the grid from unnecessary stress.

More EV Claims, Untangled

The Guardian’s “EV mythbusters” series, written by financial journalist Jasper Jolly, has been incredibly helpful in furthering my own understanding of EV misinformation.

Here are some of the questions Jolly tackles, and key quotes from his findings if you don’t feel like reading the whole thing:

Do electric cars pose a greater fire risk than petrol or diesel vehicles?

Key quote: “‘All the data shows that EVs are just much, much less likely to set on fire than their petrol equivalent,’ said Colin Walker, the head of transport at the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit thinktank.” However: “There is a definite puzzle for firefighters, as battery fires require more water to put out, can burn almost three times hotter, and are more likely to reignite, according to EV FireSafe.”

Is it right to be worried about getting stranded in an electric car? Key quote: “Banishing range anxiety is tricky because it relies on electric vehicles’ use patterns as well as the charging network. It is not yet possible to say that every journey is well served … Most authorities are clear, however, that range anxiety should not be a problem for most people.”

Are electric cars too heavy for roads, bridges and car parks?

Key quote: “Some car park owners may be affected, and if electric trucks are heavier when they become widespread that could add to road maintenance costs.But almost all of the direct costs will be borne by infrastructure maintenance budgets. The ECIU’s Walker said concerns about extra weight for EVs were simply “massively overstated”. However, he added that carmakers do have a responsibility to produce smaller electric cars, after years of focusing on the most profitable SUVs.”

Do electric cars have an air pollution problem?

Key quote: “It is certainly the case that ever heavier cars almost certainly produce more [tire] particulates. Electric cars are – for now – heavier still than equivalents. But even so, [tire] pollution appears roughly comparable between petrol, diesel and electric cars.”

Are electric cars too expensive to tempt motorists away from petrol and diesel vehicles?

Key quote: “For mostly urban drivers in cities such as Los Angeles, it “makes a lot of sense” financially but it is another calculation for Texas highway drivers, Shivers said. “It’s going to be very person-specific because everybody’s case is different,” he added.

Will hydrogen overtake batteries in the race for zero-emission cars? Key quote: “The answer is no,” said Liebreich, without a moment’s hesitation. Carmakers betting on a large share for hydrogen are “just wrong”, and heading for an expensive disappointment, he added.

EV mythbusters, The Guardian, Jasper Jolly

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2024/06 ... d-car.html

Research on Earth’s Raging Heat of 2023-24 Is Picking Up

Posted on June 7, 2024 by Yves Smith

Yves here. The generally scary heat levels of this year are set to abate a bit. But a break in trends should not be mistaken for much of a change in trajectory.

By Bob Henson, a meteorologist and journalist based in Boulder, Colorado. He has written on weather and climate for the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Weather Underground, and many freelance venues. Bob is the author of “The Thinking Person’s Guide to Climate Change” and of “The Rough Guide to Climate Change,” a forerunner to it, and of “Weather on the Air: A History of Broadcast Meteorology”, and coauthor of the introductory textbook “Meteorology Today”. For five years and until the summer of 2020 he co-produced the Category 6 news site for Weather Underground. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

Fyou’ve got a chronic health concern and you suddenly get acutely sick, you and your doctors face two big issues: what’s behind your short-term crisis, and what are the implications for your longer-term health?

Our world’s “planet doctors” have been at a similar stress point for close to a year now. They’ve been scrambling to figure out why Earth’s surface – including both atmosphere and oceans – got hit with an unprecedented spike of heat that’s run from mid-2023 well into 2024. They’ve also been addressing what, if anything, the spike tells us about the next few years and beyond.

Several fresh papers are out on two unique and much-publicized factors that may have influenced the astounding global heat of 2023-24. There’s much more coming down the research pike: for example, five journals within the Nature umbrella are joining forces for a special cross-journal issue that will focus on the spike. As the submission invitationput it, “It is not yet clear what caused the various climatic anomalies in 2023, but the answers will shape our understanding of what is to come – whether 2023 was a singular outlier year, or if it is a new baseline from which warming will continue to new levels.”

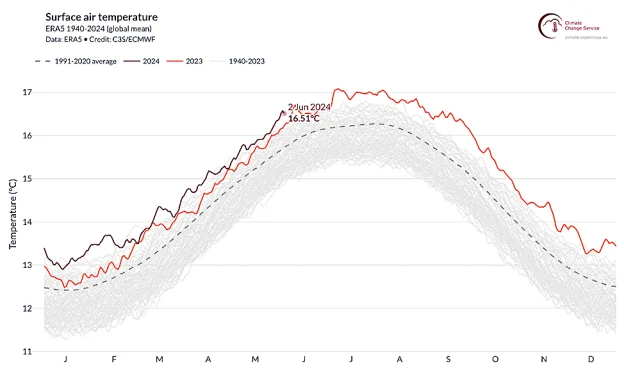

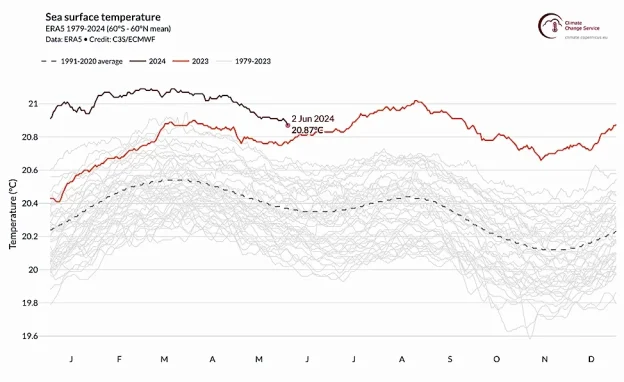

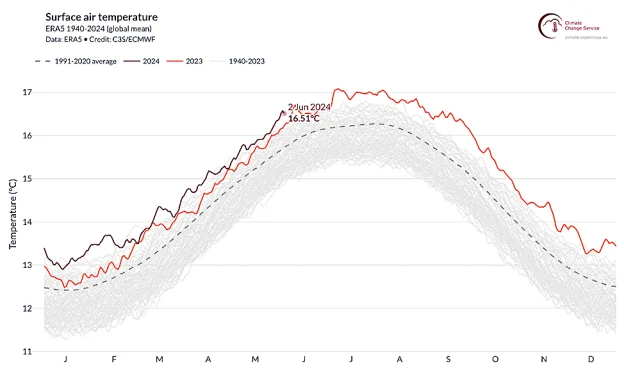

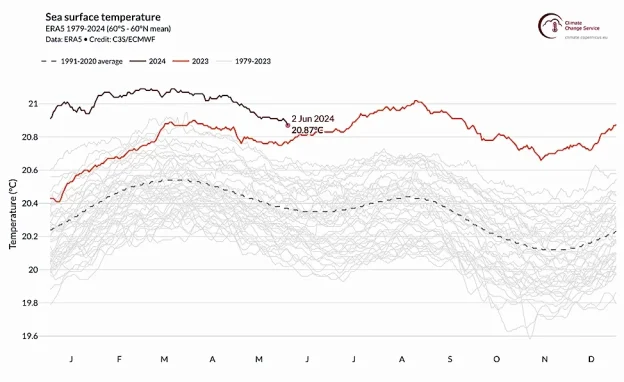

The planet’s immediate fever hasn’t yet broken. Looking at the global-scale averages calculated daily by the Copernicus Climate Change Service, surface air temperatures have set records on dozens of dates since mid-2023, and sea surface temperatures have set records each day for more than a solid year (see Figures 1 and 2 below).

Figure 1. Globally averaged daily surface air temperature from 1940 through June 2, 2024. Record global highs were set on nearly every date in the second half of 2023 and on many days in the first half of 2024. (Image credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service).

Figure 2. Globally averaged sea surface temperature (SST) from 1940 through June 2, 2024. Every date since May 4, 2023, has set a new global record for that date, and on March 20 and 21, 2024, the global SST average set the current all-time record high of 21.09°C. (Image credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service).

As catalogued here in monthly posts by Jeff Masters, every month since June 2023 has been the warmest globally in observations and analyses going back to 1850. This month NOAA and NASA will likely concur with the Copernicus Climate Change Service that May 2024 set yet another global monthly heat record.

In a special address on Wednesday (World Environment Day) titled “A Moment of Truth”, UN Secretary General António Guterres referred to the latest Copernicus data as well as a new report from the World Meteorological Organization. The WMO gave a 47% chance that the period 2024-2028 will average at least 1.5°C above preindustrial levels, and an 86% chance that at least one year in that period will set a new yearly global record, beating out 2023.

May 2024 was the hottest May in history, marking 12 straight months of hottest months ever.

Our planet is telling us something, but we don’t seem to be listening.

It’s time to mobilise, act & deliver.

It’s #ClimateAction crunch time. pic.twitter.com/7IIy5mJaxg

— António Guterres (@antonioguterres) June 5, 2024

In April alone, 34 locations set all-time monthly highs for their respective nations and territories. And in May and early June, many populous tropical and subtropical locations from India to southeast Asia to Mexico have endured miserable, dangerous heat at or or near all-time records.

Even satellite-based lower-atmosphere temperature data – long used as ammunition by those who would dismiss or deny long-term warming – haven’t escaped the intense spike.

Global warming has stopped! The pause has begun!

NO WARMING SINCE APRIL 2024! pic.twitter.com/q1FQCGyckJ

— Andrew Dessler (@AndrewDessler) June 4, 2024

The handwriting does appear to be on the wall for the demise of the 2023-24 heat spike, mainly because the Pacific is rapidly transitioning toward La Niña. The upwelling caused by La Niña typically brings immense volumes of deeper, cooler water to the surface of the eastern tropical Pacific, spanning an area that can sprawl larger than the United States. We can expect that cool infusion to bring down globally averaged air and ocean temperatures by a few tenths of a degree Fahrenheit for at least a few months. That should be enough to end the current string of daily global records and near-records, perhaps as soon as July.

It may take a lot longer to fully understand what’s happened in the last year, and what it may portend for our future.

El Niño peaked in December 2023 as one of the five strongest on record.

Because of the extra heat and moisture in our atmosphere, our weather will continue to be more extreme.

#EarlyWarningsForAll initiative remains WMO’s top priority.

https://t.co/13qHHwNYDW pic.twitter.com/tmjAiwJ3Dy

— World Meteorological Organization (@WMO) June 4, 2024

Ships, Smokestacks, and Sunlight

It should go without saying that the 2023-24 heat spike arose on top of relentless long-term warming, caused by the greenhouse gases pumped out as fossil fuels get burned. Global temperatures simply couldn’t have hit such a peak without a century-plus of global heating bolstering the spike.

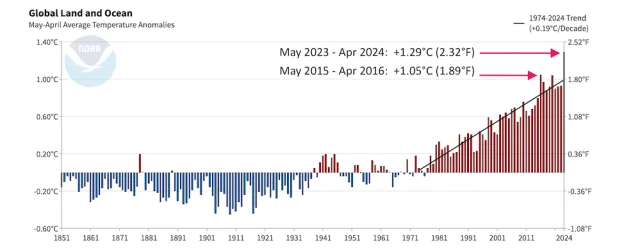

The next biggest factor was the El Niño event of 2023-24, the strongest since 2015-16 and one of the two strongest of the 21st century thus far. In contrast to La Niña, the oceanic warmth slathered across the eastern tropical Pacific by El Niño typically raises global surface air temperature by several tenths of a degree Fahrenheit.

In fact, Michael Mann (University of Pennsylvania) and others have argued that much like the El Niño heat peak of 2015-16, the 2023-24 values fall within the margin of natural variability around the longer-term warming trend.

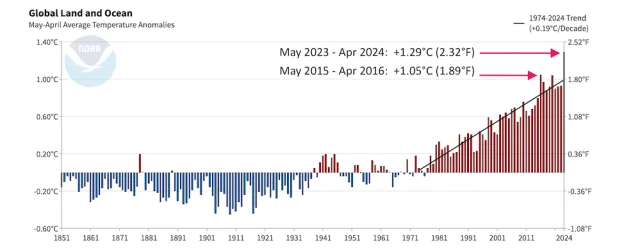

Still, there was a hefty difference of around 0.24 degree Celsius or 0.43 degrees Fahrenheit between the 2015-16 and 2023-24 peaks (based on May-to-April data from NOAA, as shown in Fig. 3 below). And questions remain: exactly how did natural variability, and/or something more, manage to produce such a jump from one strong El Niño event to the next? And why was September 2023 in particular such a record-destroyer?

It’s when you drill down past long-term warming and El Niño that the science saga gets more intriguing and more contentious.

Figure 3. Global surface temperatures (land and ocean), averaged for 12-month periods from May through April. The 2023-24 period was 0.24°C (0.43°F) warmer than 2015-16, compared to a long-term warming trend (1974-2024) of 0.15°C (0.27°F) when carried across the same eight-year period. (Image credit: Annotated from original via NOAA/NCEI)

One of the often-cited secondary factors at work is a sharp drop in the sulfate aerosol emissions spewed out from global shipping. That decline was triggered by regulations put into effect by the International Maritime Organization in 2020. They reduced sulfate emissions from shipping by some 70% and global sulfate emissions by roughly 10%.

The direct effect – fewer sun-blocking aerosols and thus more sunlight reaching Earth’s surface – is fairly straightforward. Changes in sulfates also have indirect effects: the presence of aerosols can shift the numbers and size distribution of cloud droplets, which in turn affects how much sunlight reaches Earth’s surface.

Taking both processes into account, a 2023 analysis by Carbon Brief estimated that global temperatures will be about 0.05 degrees Celsius warmer than otherwise expected by 2050 as a result of the 2020 sulfate emission cuts – in effect, speeding up global warming by about two years.

That may seem like a mere drop in the climate-change bucket. But the influx of energy has been greatest along oceanic shipping lanes – including, importantly, those across the North Atlantic, the spawning ground for U.S. Gulf and Atlantic hurricanes. Sea surface temperatures across the North Atlantic have been smashing records over most of the past year. They’re now at unprecedented heights for the start of hurricane season, as discussed here by Michael Lowry in a May 22 post.

The sea surface temperature averaged over the North Atlantic has now been record-warm for 15 consecutive months. One does start to wonder how or when it stops breaking its own records every month and year… this is not normal. pic.twitter.com/BbLPS7U43Y

— Brian McNoldy (@BMcNoldy) June 4, 2024

A new paper in Communications Earth and Environment led by Tianle Yuan (GESTAR-II/University of Maryland) estimates that the increased solar input from the drop in sulfates – which the paper calls an “inadvertent geoengineering termination shock” – could lead to a doubled rate of global warming in the 2020s compared to the last half-century. The new energy balance estimates from the Yuan paper are roughly consistent with earlier studies, but there’s been some pushback on technical grounds in the paper’s extrapolation from energy balance to global temperature trends.

“This is a timely study, but it makes very bold statements about temperature changes and geoengineering which seem difficult to justify on the basis of the evidence,” said Dr. Laura Wilcox, associate professor at the UK’s National Centre for Atmospheric Science in the University of Reading, in a roundup of reactions at Science Media Centre.

Update (June 5): Another new paper – still in preprint form at EGUSphere, and not yet peer-reviewed – describes CESM ensemble simulations that incorporate a 90% drop in sulfate emissions from shipping in 2020, and produce a delayed global-warming spike in 2023 not unlike the one actually observed.

Three new papers just added to the ongoing research surrounding the role of 2020 reduction in shipping sulfates on the recent spike in global temperatures – two suggest minor contributions while @danvisioni and colleagues find a more substantial warming. Science in action!

https://t.co/Tx1LdwfDia

— Michael Lowry (@MichaelRLowry) June 5, 2024

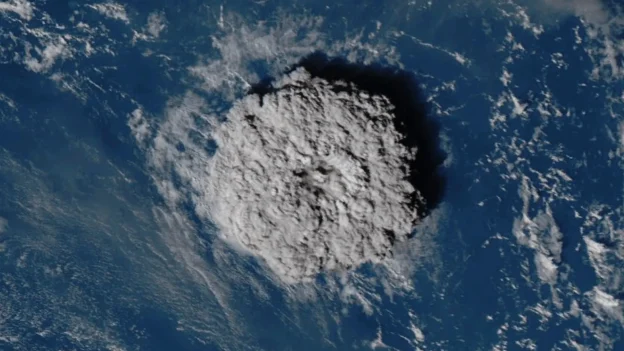

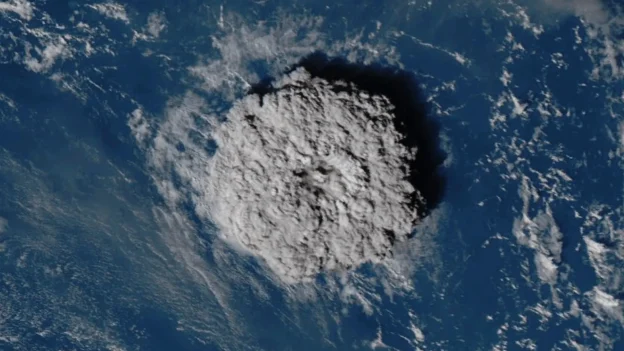

Figure 4. A view from the Himawari-8 satellite of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai volcanic eruption as it pushed above the Southwest Pacific at 0450 UTC on January 15, 2022. (Image credit: Japan Meteorological Agency, via Digital Typhoon and Wikimedia Commons)

What About That Undersea Volcano?

The eruption of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai volcano in the Southwest Pacific on January 15, 2022, grabbed the attention of vulcanologists and climate scientists worldwide. The eruption was the most powerful since that of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991.

The immense blast from Pinatubo spewed enough sulfates into the stratosphere to bring down global temperatures by as much as 0.6 Celsius (1 degree Fahrenheit) over the next year-plus. The new wrinkle with the latest eruption: Hunga Tonga is located beneath the Southwest Pacific, rather than atop an island. The eruption ended up pushing less sulfur dioxide than Pinatubo into the atmosphere, but it added a massive infusion of water vapor, enough to boost the total amount of stratospheric moisture by as much as 10 percent. The added water vapor has since worked its way to higher latitudes within the stratosphere.

As with other greenhouse gases at high altitudes, the radiative effects of the water vapor added by Hunga Tonga have been to cool the stratosphere while slightly warming Earth’s surface. A couple of early estimates were that the eruption’s sulfates led to around 0.004°C of global cooling in 2022, and that the water vapor would lead to as much as 0.035°C of global warming over five years, perhaps accounting for a minor slice of the recent global heat spike.

A paper in review at ESS Open Archive led by Mark Schoeberl (Science and Technology Corporation) estimates that the net effect from both water vapor and sulfate aerosols from Hunga Tonga has actually been a tiny cooling of Earth’s surface, and that the combined radiative effects were nearly gone by the end of 2023. The study does not evaluate conditions above 35 km in the stratosphere, where water vapor remains roughly 10 to 20 percent more prevalent than before the eruption, as the effects on climate from water vapor at such high altitudes have been considered negligible.

The transition to higher altitude is particularly pronounced.

It’s plausible, e.g. Solomon et al. 2010, that this greatly reduces the climate impact of this water vapor, but I also wonder how well we really understand these changes, which have essentially never been seen before. pic.twitter.com/EVAZA3u3Z7

— Dr. Robert Rohde (@RARohde) May 7, 2024

Another recent paper, this one just published in the Journal of Climate, asserts that we could see a complex web of regional weather and climate effects for years to come as a result of Hunga Tonga’s water vapor. Led by Martin Jucker (University of New South Wales), the paper uses the WACCM global climate model, which incorporates stratospheric chemistry, to simulate a Hunga Tonga-like eruption and its impacts up to a decade out.

The study’s estimate of global warming from the added water vapor was a mere 0.015 degrees Celsius. What’s much more striking is a projected reshuffling of weather patterns over the latter half of the 2020s, apparently caused by interacting circulation changes and cloud feedbacks. If this new study’s projections end up on target, winter warming across the northern high latitudes (including the Arctic) and springtime warming across much of Eurasia could intensify, while Australian winters could be cooler and wetter than average, all else being equal. There are also hints of El Niño conditions being favored in the tropical Pacific.

Discussing these and other “surprising, lasting impacts” in an essay for The Conversation, Jucker added: “…we hope that our study will stir scientific interest to try and understand what such a large amount of water vapor in the stratosphere might mean for our climate.”

Yet another (but very minor) factor is the timing of the ongoing peak in the 11-year solar cycle. Variations in solar heat energy across the cycle are minimal (less than 1%) compared to the forcing from greenhouse gases, and the ups and downs of the cycle don’t affect our long-term warming trajectory. Still, the sun is now approaching the peak of Solar Cycle 25, spitting out active regions (and triggering a spectacular auroral display in May), so there may be a tiny, temporary dollop of extra solar energy in the mix right now. This cycle has been more active than predicted, even if it’s still among the weakest of the last 200 years.

The Main Headline Hasn’t Changed

For all the cool science it’s generating, the 2023-24 heat spike is first and foremost a danger sign. Even assuming that globally averaged air and sea temperatures manage to drop a bit below record levels for the next one to several years – something that’s quite possible, perhaps even likely – the spike has given us a preview of what might become “normal” as soon as the 2030s, as greenhouse gases from human activity continue to accumulate in the atmosphere. That accumulation will continue even when global emissions level out and begin to drop, as may happen over the next several years. Only when emissions drop to near zero will the accumulation cease.

Given how strange the spike has been, it’s wise not to assume too much about its demise just yet. One of the most ominous recent takes is from eminent NASA climate scientist James Hansen, who asserted with coauthors in a 2023 Oxford Open Climate Change paper, Global Warming in the Pipeline, that declining global aerosol emissions (including the cuts triggered by the new shipping regulations) will accelerate the planetary warming rate well beyond standard projections.

Zeke Hausfather offered a counterpoint in a Carbon Brief post on April 4, stressing that some acceleration in warming has long been projected by models and that the 2023-24 spike may not signal anything unusual: “There is a risk of conflating shorter-term climate variability with longer-term changes – a pitfall that the climate science community has encountered before.”

An ongoing thread launched with a RealClimate post on May 30 is highlighting new research and data points related to the 2023 extremes. Post author Gavin Schmidt, who succeeded Hansen as director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, also penned a commentary in Nature on March 19 entitled Climate models can’t explain 2023’s huge heat anomaly — we could be in uncharted territory. In that writeup, Schmidt stressed:

…the 2023 temperature anomaly has come out of the blue, revealing an unprecedented knowledge gap perhaps for the first time since about 40 years ago, when satellite data began offering modelers an unparalleled, real-time view of Earth’s climate system. If the anomaly does not stabilize by August — a reasonable expectation based on previous El Niño events — then the world will be in uncharted territory.”

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2024/06 ... ng-up.html

In Virginia, Data Centers Collide with Zero-Carbon Goals

Posted on June 6, 2024 by Yves Smith

Yves here. This post on data centers and their energy costs is another “micro illuminating the macro” piece, along with our post today on Mount Sinai. We and other sites have been pointing out the well-anticipated development, that AI and crypto are producing even more computer use, to the degree that it is resulting in more data center energy hogging. And that conflicts greatly with the need to preserve some semblance of civilization as we know it by cutting energy use.

Interestingly, Virginia is not capitulating (at least not immediately) to tech industry demands. By contrast, the Biden Administration is trying to have it both ways, as OilPrice reports in Biden Wants Big Tech To Invest in Power Generation for AI Boom. Having said that, yes it is true that zero-carbon is not an ambitious enough goal, so it’s disheartening to see even this line as hard to hold.

By Sarah Vogelsong, a freelance journalist based in Richmond, Virginia. Originally published at Inside Climate News

While short-lived, the denial came as a surprise.

This March, Loudoun County, a suburb of Washington, D.C. in Northern Virginia that is home to the greatest concentration of data centers in the world, made an unexpected move: It rejected a proposal to let a company build a bigger data center than existing zoning automatically allowed.

“At some point we have to say stop,” said Loudoun Supervisor Michael Turner during the meeting, as reported by news site LoudounNow. “We do not have enough power to power the data centers we have.”

County supervisors would later reverse the decision, approving a smaller version of the project. But the initial denial sent ripples throughout Virginia, where concern over the rapid growth of data centers and what that means for the state’s ambitious decarbonization goals is growing.

“It is really a salient issue for climate right now,” said Tim Cywinski, a spokesperson for the Virginia chapter of the Sierra Club, which has been vocal about its desire to slow down data center development in the state. “The data center industry is about 2 percent of global carbon emissions,” he said, adding “In about two years, I think it will surpass the airline industry.”

Dominion Energy, Virginia’s largest electric utility, has forecast that data centers will be the most significant driver of rising energy demand in the state over the next 15 years. And while the utility has pledged it will decarbonize its Virginia grid by 2045, in line with the Virginia Clean Economy Act passed by the state legislature in 2020, it has also indicated in its most recent long-range plan for utility regulators that new natural gas plants will be needed to meet demand.

“We are 100 percent committed to achieving the goals of the VCEA. We are not taking our foot off the accelerator with renewables,” said Aaron Ruby, a spokesperson for Dominion. But, he added, “the clean energy transition is more challenging than it was a few years ago. The inescapable reality is we are experiencing unprecedented growth in electric demand.”

While some environmentalists say the skyrocketing data center growth threatens Virginia’s ability to go zero-carbon, others say it can be done — but it will require new ways of managing the grid.

“To me it’s not a question of data centers or clean energy,” said Nate Benforado, an attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center. “I think there is a path forward if we make some improvements.”

Data centers and Virginia have been hand in glove for almost three decades, since companies like MAE-East, Equinix and AOL built some of the earliest modern facilities in the Washington suburbs. With close proximity to the federal government and the defense firms ringing it, Northern Virginia — and especially Ashburn in Loudoun County, known as “Data Center Alley” — quickly became the beating heart of the U.S. data center industry.

“There are data centers located in other areas of Virginia, but roughly 80% of the industry is located in Loudoun County,” Dominion wrote in a recent long-term plan submitted to state regulators. “To put this in perspective, the aggregate of the next six largest data center markets in the U.S. is not as big as Loudoun County’s market.”

Lawmakers have embraced the business. Beginning in 2010, Virginia exempted data centers from sales and use tax for many of the key components of their business as long as they met certain criteria: They had to invest at least $150 million in their facility, create 50 new jobs in the locality where it was sited, and pay at least 150 percent of the prevailing annual average wage. The exemption remains Virginia’s largest economic development incentive.

The gambit worked. A 2019 report by Virginia’s legislative watchdog, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, found the exemption “has a sizable influence” in attracting data centers to the state. It also has a “moderate economic benefit” for the state, generating about $27 million in Virginia gross domestic product for every $1 million in foregone tax revenue, JLARC concluded.

But as data centers have continued to flock to Virginia, concerns have increased. In Loudoun and neighboring Prince William County, residents complain the facilities’ 24/7 operations produce a constant humming that never stops. Conservationists fear the centers’ expanding footprint is consuming too much land, while their heavy water use could strain local supplies.

How to deal with the facilities’ power use is also an increasingly urgent question. Data centers are highly electricity-intensive, requiring a steady stream of power to operate around the clock. As the industry expands, more electricity is needed to meet their demand, triggering the construction of not only new sources of power but transmission lines to carry that power from where it’s generated to where it’s used.

Data center representatives have pointed out many companies in the space have been active drivers of renewables development across the nation. In a statement, Data Center Coalition President Josh Levi noted two-thirds of the renewable power bought by U.S. corporations has been wind and solar contracted to data centers and their customers. Companies have also set their own goals: Google aims to operate its data centers on carbon-free energy by 2030, while Amazon is pushing for net-zero carbon emissions by 2040.

“Data centers are highly efficient facilities that enable energy savings and efficiencies for homes, businesses, utilities and other end users,” said Levi. Many, he added, are “on pace to achieve voluntary clean energy targets that predate and outpace many state mandates and targets.”

Even with those commitments, the sheer magnitude of the facilities’ growth in Virginia poses a challenge for utilities, and particularly Dominion. While data centers’ peak energy usage in 2022 was almost 2.8 gigawatts — roughly one and a half times the power produced at Dominion’s largest Virginia plant, the North Anna nuclear facility in Louisa County — the company forecasts they will require roughly 13.3 gigawatts by 2038. Much of that may be due to Amazon Web Services, which Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin last year announced intends to invest $35 billion in data center campuses in the state by 2040, although Dominion does not disclose information about specific customers.

“The amount of data center load growth we’re dealing with is absolutely phenomenal,” said Devi Glick, a principal at consultancy Synapse Energy Economics, who testified for the Sierra Club at hearings in Richmond this September on the utility’s Integrated Resource Plan, a non-binding roadmap for how it intends to meet customer demand over the next 15 years. “Everything we’re dealing with is massive and kind of, like, novel.”

Some environmental groups have challenged the accuracy of Dominion’s forecasts, arguing the utility is overestimating future growth as a way to justify keeping existing natural gas plants running and build new ones, including a proposed peaker plant in Chesterfield County.

Others, including nonprofit Appalachian Voices, say the forecast is shakier than it appears because so much of the expected demand comes from a very small number of companies. According to figures from Dominion, two firms account for 62 percent of the demand the utility expects to see from data centers in 2030. Five account for 80 percent.

“If even one of those five companies changes its growth plans, or if one or more counties in northern Virginia takes an aggressively hostile turn against data center expansion, the actual growth in Virginia could be radically different from what Dominion estimates now,” wrote Rachel James, an attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center representing Appalachian Voices, this October.

Despite those disagreements, there’s little debate that in the near term, data centers’ electricity demand is skyrocketing. Dominion Vice President of Strategic Partnerships Alan Bradshaw told regulators this September that data centers have signed electric service agreements with Dominion that call for the utility to provide over 5.8 gigawatts to various new facilities by 2032. Bradshaw said he wasn’t aware of any data center customer in Dominion territory abandoning a project after such an agreement had been signed. Over 10 additional gigawatts are in earlier stages of development by companies working with Dominion to obtain power for future projects.

“This week we’ve had an executive meeting with a new entrant on the market, and they want to add two campuses that have 1.2 gigawatts of load,” Bradshaw said at the Sept. 21 hearing. “Literally on the way to the courthouse today, we had another customer call us about a half-gigawatt campus they want to meet with us on. So they just continue to come.”

But while economic development boosters see the uptick in investment as a boon for state and local coffers, environmental groups say if left unchecked, the growth threatens Virginia’s ability to decarbonize its electric grid by 2050.

“We have to make the hard choice about what data centers look like in Virginia now and if it’s worth the cost,” said Cywinski of the Sierra Club. “And right now, we think it’s not.”

All of the long-range plans Dominion presented to regulators last year included new natural gas capacity, ranging anywhere from 970 to 2,900 megawatts of the fuel, an approach the company has defended as necessary to ensure reliability.

“There is no realistic way that we can serve all this growth, keep our customers’ power on around the clock, and only do it with renewables,” said Ruby, the Dominion spokesman. “That is just not realistically possible.”

Ruby said the utility’s calculus isn’t just based on available megawatts. It’s also a matter, he said, of how quickly units can be brought online to meet demand in a crisis. Solar and wind can’t produce electricity around the clock, and while nuclear will remain a mainstay of Virginia power supply — it currently accounts for about a third of Dominion’s Virginia capacity — both the North Anna and Surry plants require hours to ramp up.

In contrast, he said, with a natural gas plant like the new Chesterfield facility the utility has proposed, “we can ramp that up and dispatch 1,000 megawatts to the grid in 10 to 20 minutes.”

Environmental groups, however, say Dominion shouldn’t be planning to expand its carbon resources in the long term given state law requiring the utility to stop emitting carbon by the middle of the century.

“The transition to clean energy, that is the commonwealth’s policy. It is in the law. That is what we are working towards,” said Benforado, who along with James represented Appalachian Voices in the September case.

How data centers’ rising power demands may impact Virginia’s ability to transition from fossil fuels to renewables is one of the issues the state’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission is tasked with assessing this year. And although lawmakers put forward more than a dozen proposals related to data centers during the last legislative session, the General Assembly delayed consideration of most until the next session, after the state study’s release. Among the bills put forward were proposals to require data centers to meet certain energy efficiency targets to qualify for state tax incentives and have local governments study the regional grid impacts of potential facilities.

“The JLARC study really sucked the wind out of a lot of these,” said Benforado.

In regulatory proceedings, Appalachian Voices and the Sierra Club have argued that rather than building new gas plants, Dominion should explore other ways to meet data centers’ power needs. Proposals include demand response programs that let energy consumers shift or reduce their power usage during times of high demand, such as extremely cold or hot weather. The environmental groups also argued for long-duration battery storage, an emerging but limited technology, and transmission upgrades.

“I think we need much more sophisticated planning that looks at lots of options, lots of tools,” said Benforado. “I do not accept this idea that we have to build gas. … To me, that’s not backed up by analysis.”

With as many as 11 gigawatts of power needed over the next 15 years to supply data centers, he said, “I think this is the time we need to refocus our efforts.”

“Clean energy aside, if you don’t have smart planning, optimized solutions, it’s going to be really expensive to supply 11 gigawatts,” he said.

Levi of the Data Center Coalition noted that “grid planning and management is ultimately the role of utilities and grid operators.” However, he said the industry “is committed to leaning in as an engaged partner.”

Rising tensions could complicate the search for solutions. Local conflicts over the industry have led to the ousting of at least one official in Prince William County, and in December 2023, 25 nonprofits and other groups, including the Virginia chapter of the Sierra Club, announced they were forming the Virginia Data Center Reform Coalition to seek more regulation of data centers.

Still, Benforado said he believed “win-win solutions” could be found in partnership with the industry.

“I think they’re motivated,” he said. “I hope they’re motivated.”

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2024/06 ... goals.html