“Our stomachs will make themselves heard”: What Sankara can teach us about food justice today

“Our stomachs will make themselves heard”: What Sankara can teach us about food justice today

Selected posts and additional material from http://www.thebellforum.net/Bell2/www.t ... l?t=150246

***************************

“Our stomachs will make themselves heard”: What Sankara can teach us about food justice today

Amber Murrey

| May 05, 2016

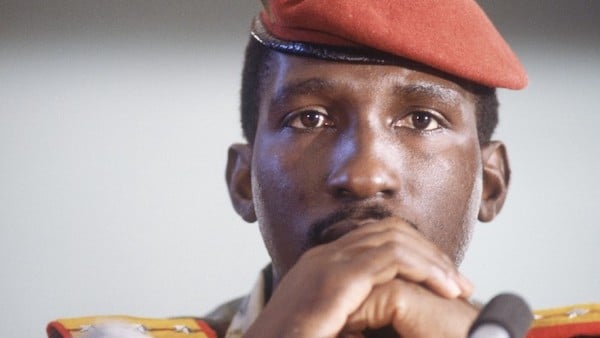

When it comes to food justice, environmentalism and ecological practices, Thomas Sankara was way ahead of his time. Thomas Sankara helped Burkina Faso become self-sufficient before in basic foodstuffs in just a few years before he was assassinated.

In recent weeks, news of food crises in countries across Africa has been intensifying. From the Democratic Republic of Congo all the way down to South Africa – via Malawi, Zimbabwe, Angola and many others – low rainfall has contributed to millions more being left vulnerable.

Earlier this week the international NGO, Save the Children, reported that the food shortage in the drought-affected Tigray and Afar regions of northern Ethiopia has reached critical proportions.[1] Of the 30 million people living in the region, according to UNICEF and the Ethiopian government, one third of them—some 10 million people—are in need of emergency food assistance.[2] The US government is now coordinating food aid and relief efforts, announcing last month that it would supplement $532 million for emergency food assistance, safe drinking water and nutrition.[3]

Yet, direct food aid is often destructive, particularly in the long-term, for those on the receiving end. Historical examinations of famine and the aftermaths of crisis response have shown that direct food aid, rather than reducing hunger, actually suppresses local food production and distribution systems. This market suppression, in turn, contributes to the structural inequalities that sustain uneven food distribution. Uneven food distribution within the global circuits of capitalism is at the heart of modern-day hunger.[4]

The current drought in northern Ethiopia echoes the 2005/06 drought in the Somali and Afar Regions as well as the Borena Zone of the Oromia Region—precisely because endemic, cyclical food shortage is a product of uneven economic development and is further compounded by anthropogenic climate change. [5]

However, hunger is far from inevitable on the continent and there is an alternative African story worth retelling, one of food sovereignty, security and self-sufficiency, and one whose lessons could be revived today. Thomas Sankara’s ecological-political praxis provides an alternative framework for food justice on the continent.

“You don’t need us to go looking for foreign financial backers”

During his short political career—which prematurely ended when he was assassinated in 1987—Sankara argued that some of the most pervasive roots of ecological disaster and hunger were over-indebtedness and over-dependence on foreign aid structures that encourage bare survival. Not only is his political-ecological praxis and his emphasis on national food sovereignty in a context of pervasive food aid still relevant for conversations about food justice today, but the successful implementation of several ecological programs in Burkina Faso provides historical evidence for the significance of national sovereignty and collective ecological practices for cultivating food security in arid and drought-prone landscapes (such as Northern Ethiopia and Burkina Faso).

In the four years that he was the president of the West African country of Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara courageously worked with people on projects of self-determination in the face of enormous international and domestic neo-imperialist pressures. Known for his pro-people restructuring of the Burkinabè state, his staunch anti-imperialisms and his efforts to unite African leaders to repudiate international debt, his ecological practices have been relatively overlooked until recently. [6]

Sankara was an anti-imperial political activist-cum-intellectual revolutionary who actively and charismatically cultivated egalitarian political policies to improve the wellbeing of Burkina Faso’s seven million citizens in the mid-1980s. Sankara insisted that too many of the challenges that Burkinabè[7] people faced on a daily basis—including hunger, thirst, desertification, illiteracy, gender inequality[8] and economic alienation—were rooted in neo-colonial political and economic relationships and structures.

At the same time that the World Bank and the IMF were implementing sweeping austerity policies under the auspices of the Structural Adjustment Programs across the African continent, [9] Sankara was engaging in a transformative and revolutionary political project. This was a collective project to restructure the post-colonial state of Burkina Faso to ensure that state policies and political structures worked for the wellbeing of the people. For Sankara, meaningful anti-colonial political projects were rooted in self-sufficiency that ‘refused to accept a state of [mere] survival’ and ‘open[s] minds to a world of collective responsibility in order to dare to invent the future’. [10]

At the 39th General Assembly of the United Nations in New York, Sankara made clear the relationship between neo-imperialism and hunger in post-colonial Burkina. He said,

‘We must succeed in producing more—producing more, because it is natural that he who feeds you also imposes his will […] We are free. He who does not feed you can demand nothing of you. Here, however, we are being fed every day, every year, and we say, “Down with imperialism!” Well, your stomach knows what’s what.’

[Laughter and applause was heard from the crowd.]

‘Even though as revolutionaries we do not want to express gratitude, or at any rate, we want to do away with all forms of domination, our stomachs will make themselves heard and may well take the road to the right, the road of reaction, and of peaceful coexistence [Applause from the crowd] with all those who oppress us by means of the grain they dump here.’

His anti-imperial language was audacious and ground-breaking but his assertions about the use of food distribution as a mechanism of control and power have since been further substantiated. This ‘dumping’ (to echo Sankara’s language) of food is, precisely, oftentimes profitable for donor countries. Since the inauguration of the US foreign food aid program in 1954,[11] the program has been structured primarily as ‘tied aid’. Frances Moore Lappé and Joseph Collins explain that US food aid typically ‘must be grown, processed, and packaged in the United States and shipped overseas on US-flagged vessels’.[12] An Oxfam Briefing Paper from 2006 similarly asserts that the US,

‘Sometimes uses food aid to dump agricultural surpluses and to attempt to create new markets for its exports. Indeed, food aid has the potential both to reduce domestic production of food, damaging the livelihoods of poor farmers, and to displace exports from other countries into the recipient country’.[13]

More than twenty years before the Oxfam report, Sankara argued that humanitarian aid was counterintuitive to long-term wellbeing that would move Burkinabè society past mere survival in a neo-colonial global system. Sankara combined a formidable anti-imperialism with a conviction in the power of the people and encouraged people’s struggle and mobilisations in the face of thirst and hunger. Sankara urged the people of Burkina,

‘You are going to build in order to prove that you’re capable of transforming your existence and transforming the concrete conditions in which you live. You don’t need us to go looking for foreign financial backers, you only need us to give the people their freedom and their rights. That will be done’.[14]

One village, one grove

Along with his insistence on national food sovereignty (often refusing international aid) and boosting local production, new irrigation canals were constructed. Sankara endeavoured to implement a nation-wide system of agro-ecology. Agro-ecology is an approach that encourages ‘power-dispersing and power creating’ communal food cultivation that enhances ‘the dignity, knowledge and capacities of all involved’ and the regeneration of the environment.[15] Agro-ecological pioneer, Pierre Rabhi, who worked in Burkina in the 1980s, explains that Sankara ‘wanted to make agro-ecology a national policy’.[16]

To end systemic hunger, Sankara worked collaboratively to implement a revised political economy focused on the capacity to provide every Burkinabè two meals a day and clean water. Two meals a day and clean water was a radical project in the context of persistent drought and famine across the Sahel. He insisted that the Burkinabè revolution

‘be measured by something else, it will be measured by the level of production. We must produce, we must produce. That’s why I welcome the slogan, “two million tons of grain.”’

Sankara focused on combating desertification in the Sahel. For Sankara, self-reliance and independence was a constituent of human dignity. These two political commitments are reflected in his linking of self-sufficiency with ecological sustainability and are apparent through the ‘un village, un bosquet’ (one village, one grove) program. The program encouraged every town, beginning with Ouagadougou, to plant trees to mark social occasions. These trees would eventually become a forest on the outer edges of the town. Before the global rise of the discourses of environmentalism, Sankara implemented a tree-planting campaign that transformed the arid landscape of Burkina.

The program re-established a culture of people-led, grassroots tree planting. This mixing of forestlands and farmlands was historically practiced throughout West Africa but the practice had been suffocated by the colonial domination of land use.[17] Sankara re-linked the practice of tree planting to pre-colonial tradition, emphasizing both the usefulness of tree planting as well as valorising it as custom of Burkina.[18]

The programs were enormously successful. In four years, 10 million trees were planted across the Sahel. Meanwhile, Jean Ziegler, the former UN special rapporteur on the right to food, declared that hunger had been eradicated in Burkina.

Lessons for today

Sankara lived a politics that was committed to a holistic revival of health and wellbeing – one that was inclusive of the environment, women and the masses. As Minister of Information under Colonel Saye Zerbo in 1981, Sankara pedalled to work on a bicycle. Later, one of his first acts as president was to create a Ministry of Water—this was ‘the first time the country had a ministry devoted exclusively to that essential resource’.[19]

Meng-Néré Fidèle Kientega, who worked closely with Sankara before his death and the current Secretary of External Relations of the Burkina Faso National Assembly, said of Sankara’s commitment to ecological and food justice,

‘Even if the validity of certain commitments and actions of the Revolution are subject to debate, it is indisputable that, from the environmental point of view as well as the ecological, Burkina today would have presented a different face [had Sankara’s ecological approach survived] than the [current] decrepitude and hazardous sell of pesticides everywhere, the plastic packaging that suffocates our land and restrains our animals, and the GMOs [that proliferate] in spite of outcry and almost universal disapproval’.[20]

Drawing inspiration from Sankara, the organisation, Terres Vivants-Thomas Sankara (Living Earth-Thomas Sankara), is working to reinvigorate some of Sankara’s pioneering commitments to agro-ecology, food sovereignty and ecological regeneration in Burkinabè villa communities.[21] These efforts indicate some of the ways in which Sankara’s ecological-political praxis remains a powerful rubric for food justice today. Rather than ask how ‘we’ let it (i.e., famine) happen ‘again’[22]—(and, in so doing, invoke memories of the highly criticised and patronising US musical response to the 1984 Ethiopian famine, ‘We are the World’)—we might articulate increasingly holistic understandings of ecology, climactic variability, markets, community wellbeing and international food aid in the context of food justice. Burkina’s August Revolution reveals some of the potentials within community-led efforts to re-forest when they are combined with grassroots educational programs and sustained political and economic efforts for food sovereignty.

Sankara emphasised the importance of people-powered national sovereignty for sustainable food justice. And his ground-breaking efforts to work with the people to increase awareness of the environment through incremental everyday activities and to carry out concrete programmes to foster long-term agro-ecological balance for food justice remain a powerful rubric for food justice today.

As international food aid and relief programmes move to intervene in the present famines by “dropping” millions of tons of food to provide short-term relief, we might recall Sankara’s courageous assertions that food aid is too often destructive in the long-term. His emphasis on national food sovereignty in a context of pervasive food aid shows that promoting national production and encouraging collective agro-ecology can be enormously successful in addressing the roots of hunger, even in drought-prone landscapes.

* Amber Murrey recently completed her PhD in Geography and the Environment from the University of Oxford. She teaches Development Studies at Jimma University in Jimma, Ethiopia. Amber is currently collaborating to put together an Edited Volume on Sankara’s political praxis. She can be reached at ambermurrey@gmail.com.

Notes

[1] The drought has been caused by two consecutive failed rainy seasons (aggravated by global climate change) and an ocean warming El Niňo. See Drought leaves 6 million Ethiopian children hungry, Aljazeera.

[2] Country Report for Ethiopia (2016) UNICEF Humanitarian Action for Children.

[3] Nicole Gaouette (2016) US Dispatches Emergency Aid for Ethiopian Drought. CNN Politics.

[4] Tate Munro and Lorenz Wild (2016) As Drought Hits Ethiopia Again, Food Aid Risks Breaking Resilience. The Guardian.

[5] For more systematic examinations of the cyclical production of famines, the uneven global distribution of food and contemporary issues of food justice see the work of Amartya Sen (Poverty and Famines), Tanya Kerssen (Grabbing Power), Eric Holt-Gimenez, Michael Watts (Silent Violence), Raj Patel (Stuffed and Starved), Alex de Waal (Famine Crimes) and Vandana Shiva.

[6] Mike Speir’s (1991) examination of food self-sufficiency under the Conseil National de la Rèvolution (CNR) is a notable exception. See Speir (1991) ‘Agrarian change and the revolution in Burkina Faso’. African Affairs 90(358), pp. 89-110. More recently, ABC Burkina’s Newsletter (2012) was devoted to Sankara’s ecological heritage, edited by Maurice Oudet, Director SEDELAN, see particularly Fidel Kientega’s contribution Sankarisme et l’Environnement.

[7] Here I use the Fulfulde spelling (è) thereof.

[8] Amber Murrey (2012) The Revolution and the Emancipation of Women—Thoughts on Sankara’s Speech, 25 Years Later. Pambazuka News.

[9] African countries had an estimated combined $200 billion in foreign debt in 1985, with many countries spending nearly 40 per cent of annual budgets in debt repayment. Sankara famously said in his July 1987 address at the Summit of the Organization for African Unity (OAU): ‘Africa, collectively, simply refuse to pay’.

[10] Thomas Sankara’s speech at the 39th Assembly of the United Nations General Assembly. New York: 4 Oct. 1984.

[11] Public Law (PL) 480 was signed into law as the Agricultural Trade Development Act by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on 10 July 1954.

[12] Frances Moore Lappé and Joseph Collins (2015) World Hunger: Ten Myths. In Food First Backgrounder 21(2).

[13] Oxfam International (2006) Food Aid or Hidden Dumping? Separating Wheat from Chaff. Oxfam Briefing Paper 71.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Frances Moore Lappé and Joseph Collins (2015) World Hunger: Ten Myths. In Food First Backgrounder 21(2).

[16] See Rabhi’s interview in Part 1 of Sur les traces de Thomas Sankara. Documentary film. 90 min. Burkina Faso and France: Baraka Studios.

[17] Sankara attempted to radically restructure the land regime in Burkina through the RAF or the loi portant réorganisation agraire et foncière (law on the re-organisation of agriculture and soil). The successfulness of this land paradigm, which abolished private land ownership and replaced land title with usage rights, has been questioned and criticised (see Mahmadou Zongo, 2009, ‘Terre d’etat, loi des ancêstres? Les conflits fonciers et leurs procédures de règlement dans l’ouest du Burkina Faso’ Cahiers du Cerleshs Tome XXIV(33), 1191145.

[18] The programme was implemented, as Harsch (2014, pp. 102) notes, after the unsuccessful ‘three struggles’ campaign, which had criminalised behaviours deemed unsustainable (including slash-and-burn practices, the consumption of bush meat and tree-cutting in certain areas).

[19] Harsch, pp.100.

[20] Fidel Kientega (2009) Sankarisme et Environnement. Presentation delivered at La première édition de Sankara Revival, an initiative of Musician Sams’K Le Jah. Originally in French (loose translation by author): ‘Si la justesse de certains engagements et actions de la Révolution peut être sujette à discussion, il est incontestable que du point de vue de l’environnement et de l’écologie, le Burkina aurait présenté aujourd’hui un autre visage que celui de la décrépitude et de l’option hasardeuse pour les pesticides à tout vent, les emballages plastiques qui désolent toutes nos terres et endeuillent tous nos éleveurs, les OGM au grand dam du tollé et de la désapprobation quasi-générale.’

[21] See ABC Burkina’s Newsletter (2012) devoted to Sankara’s ecological heritage, edited by Maurice Oudet, Director of SEDELAN.

[22] James Jeffrey (2016) Ethiopia Drought: How Can We Let This Happen Again? Aljazeera.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR/S AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

-found via FB. http://www.pambazuka.org/food-health...=socialnetwork

***************************

“Our stomachs will make themselves heard”: What Sankara can teach us about food justice today

Amber Murrey

| May 05, 2016

When it comes to food justice, environmentalism and ecological practices, Thomas Sankara was way ahead of his time. Thomas Sankara helped Burkina Faso become self-sufficient before in basic foodstuffs in just a few years before he was assassinated.

In recent weeks, news of food crises in countries across Africa has been intensifying. From the Democratic Republic of Congo all the way down to South Africa – via Malawi, Zimbabwe, Angola and many others – low rainfall has contributed to millions more being left vulnerable.

Earlier this week the international NGO, Save the Children, reported that the food shortage in the drought-affected Tigray and Afar regions of northern Ethiopia has reached critical proportions.[1] Of the 30 million people living in the region, according to UNICEF and the Ethiopian government, one third of them—some 10 million people—are in need of emergency food assistance.[2] The US government is now coordinating food aid and relief efforts, announcing last month that it would supplement $532 million for emergency food assistance, safe drinking water and nutrition.[3]

Yet, direct food aid is often destructive, particularly in the long-term, for those on the receiving end. Historical examinations of famine and the aftermaths of crisis response have shown that direct food aid, rather than reducing hunger, actually suppresses local food production and distribution systems. This market suppression, in turn, contributes to the structural inequalities that sustain uneven food distribution. Uneven food distribution within the global circuits of capitalism is at the heart of modern-day hunger.[4]

The current drought in northern Ethiopia echoes the 2005/06 drought in the Somali and Afar Regions as well as the Borena Zone of the Oromia Region—precisely because endemic, cyclical food shortage is a product of uneven economic development and is further compounded by anthropogenic climate change. [5]

However, hunger is far from inevitable on the continent and there is an alternative African story worth retelling, one of food sovereignty, security and self-sufficiency, and one whose lessons could be revived today. Thomas Sankara’s ecological-political praxis provides an alternative framework for food justice on the continent.

“You don’t need us to go looking for foreign financial backers”

During his short political career—which prematurely ended when he was assassinated in 1987—Sankara argued that some of the most pervasive roots of ecological disaster and hunger were over-indebtedness and over-dependence on foreign aid structures that encourage bare survival. Not only is his political-ecological praxis and his emphasis on national food sovereignty in a context of pervasive food aid still relevant for conversations about food justice today, but the successful implementation of several ecological programs in Burkina Faso provides historical evidence for the significance of national sovereignty and collective ecological practices for cultivating food security in arid and drought-prone landscapes (such as Northern Ethiopia and Burkina Faso).

In the four years that he was the president of the West African country of Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara courageously worked with people on projects of self-determination in the face of enormous international and domestic neo-imperialist pressures. Known for his pro-people restructuring of the Burkinabè state, his staunch anti-imperialisms and his efforts to unite African leaders to repudiate international debt, his ecological practices have been relatively overlooked until recently. [6]

Sankara was an anti-imperial political activist-cum-intellectual revolutionary who actively and charismatically cultivated egalitarian political policies to improve the wellbeing of Burkina Faso’s seven million citizens in the mid-1980s. Sankara insisted that too many of the challenges that Burkinabè[7] people faced on a daily basis—including hunger, thirst, desertification, illiteracy, gender inequality[8] and economic alienation—were rooted in neo-colonial political and economic relationships and structures.

At the same time that the World Bank and the IMF were implementing sweeping austerity policies under the auspices of the Structural Adjustment Programs across the African continent, [9] Sankara was engaging in a transformative and revolutionary political project. This was a collective project to restructure the post-colonial state of Burkina Faso to ensure that state policies and political structures worked for the wellbeing of the people. For Sankara, meaningful anti-colonial political projects were rooted in self-sufficiency that ‘refused to accept a state of [mere] survival’ and ‘open[s] minds to a world of collective responsibility in order to dare to invent the future’. [10]

At the 39th General Assembly of the United Nations in New York, Sankara made clear the relationship between neo-imperialism and hunger in post-colonial Burkina. He said,

‘We must succeed in producing more—producing more, because it is natural that he who feeds you also imposes his will […] We are free. He who does not feed you can demand nothing of you. Here, however, we are being fed every day, every year, and we say, “Down with imperialism!” Well, your stomach knows what’s what.’

[Laughter and applause was heard from the crowd.]

‘Even though as revolutionaries we do not want to express gratitude, or at any rate, we want to do away with all forms of domination, our stomachs will make themselves heard and may well take the road to the right, the road of reaction, and of peaceful coexistence [Applause from the crowd] with all those who oppress us by means of the grain they dump here.’

His anti-imperial language was audacious and ground-breaking but his assertions about the use of food distribution as a mechanism of control and power have since been further substantiated. This ‘dumping’ (to echo Sankara’s language) of food is, precisely, oftentimes profitable for donor countries. Since the inauguration of the US foreign food aid program in 1954,[11] the program has been structured primarily as ‘tied aid’. Frances Moore Lappé and Joseph Collins explain that US food aid typically ‘must be grown, processed, and packaged in the United States and shipped overseas on US-flagged vessels’.[12] An Oxfam Briefing Paper from 2006 similarly asserts that the US,

‘Sometimes uses food aid to dump agricultural surpluses and to attempt to create new markets for its exports. Indeed, food aid has the potential both to reduce domestic production of food, damaging the livelihoods of poor farmers, and to displace exports from other countries into the recipient country’.[13]

More than twenty years before the Oxfam report, Sankara argued that humanitarian aid was counterintuitive to long-term wellbeing that would move Burkinabè society past mere survival in a neo-colonial global system. Sankara combined a formidable anti-imperialism with a conviction in the power of the people and encouraged people’s struggle and mobilisations in the face of thirst and hunger. Sankara urged the people of Burkina,

‘You are going to build in order to prove that you’re capable of transforming your existence and transforming the concrete conditions in which you live. You don’t need us to go looking for foreign financial backers, you only need us to give the people their freedom and their rights. That will be done’.[14]

One village, one grove

Along with his insistence on national food sovereignty (often refusing international aid) and boosting local production, new irrigation canals were constructed. Sankara endeavoured to implement a nation-wide system of agro-ecology. Agro-ecology is an approach that encourages ‘power-dispersing and power creating’ communal food cultivation that enhances ‘the dignity, knowledge and capacities of all involved’ and the regeneration of the environment.[15] Agro-ecological pioneer, Pierre Rabhi, who worked in Burkina in the 1980s, explains that Sankara ‘wanted to make agro-ecology a national policy’.[16]

To end systemic hunger, Sankara worked collaboratively to implement a revised political economy focused on the capacity to provide every Burkinabè two meals a day and clean water. Two meals a day and clean water was a radical project in the context of persistent drought and famine across the Sahel. He insisted that the Burkinabè revolution

‘be measured by something else, it will be measured by the level of production. We must produce, we must produce. That’s why I welcome the slogan, “two million tons of grain.”’

Sankara focused on combating desertification in the Sahel. For Sankara, self-reliance and independence was a constituent of human dignity. These two political commitments are reflected in his linking of self-sufficiency with ecological sustainability and are apparent through the ‘un village, un bosquet’ (one village, one grove) program. The program encouraged every town, beginning with Ouagadougou, to plant trees to mark social occasions. These trees would eventually become a forest on the outer edges of the town. Before the global rise of the discourses of environmentalism, Sankara implemented a tree-planting campaign that transformed the arid landscape of Burkina.

The program re-established a culture of people-led, grassroots tree planting. This mixing of forestlands and farmlands was historically practiced throughout West Africa but the practice had been suffocated by the colonial domination of land use.[17] Sankara re-linked the practice of tree planting to pre-colonial tradition, emphasizing both the usefulness of tree planting as well as valorising it as custom of Burkina.[18]

The programs were enormously successful. In four years, 10 million trees were planted across the Sahel. Meanwhile, Jean Ziegler, the former UN special rapporteur on the right to food, declared that hunger had been eradicated in Burkina.

Lessons for today

Sankara lived a politics that was committed to a holistic revival of health and wellbeing – one that was inclusive of the environment, women and the masses. As Minister of Information under Colonel Saye Zerbo in 1981, Sankara pedalled to work on a bicycle. Later, one of his first acts as president was to create a Ministry of Water—this was ‘the first time the country had a ministry devoted exclusively to that essential resource’.[19]

Meng-Néré Fidèle Kientega, who worked closely with Sankara before his death and the current Secretary of External Relations of the Burkina Faso National Assembly, said of Sankara’s commitment to ecological and food justice,

‘Even if the validity of certain commitments and actions of the Revolution are subject to debate, it is indisputable that, from the environmental point of view as well as the ecological, Burkina today would have presented a different face [had Sankara’s ecological approach survived] than the [current] decrepitude and hazardous sell of pesticides everywhere, the plastic packaging that suffocates our land and restrains our animals, and the GMOs [that proliferate] in spite of outcry and almost universal disapproval’.[20]

Drawing inspiration from Sankara, the organisation, Terres Vivants-Thomas Sankara (Living Earth-Thomas Sankara), is working to reinvigorate some of Sankara’s pioneering commitments to agro-ecology, food sovereignty and ecological regeneration in Burkinabè villa communities.[21] These efforts indicate some of the ways in which Sankara’s ecological-political praxis remains a powerful rubric for food justice today. Rather than ask how ‘we’ let it (i.e., famine) happen ‘again’[22]—(and, in so doing, invoke memories of the highly criticised and patronising US musical response to the 1984 Ethiopian famine, ‘We are the World’)—we might articulate increasingly holistic understandings of ecology, climactic variability, markets, community wellbeing and international food aid in the context of food justice. Burkina’s August Revolution reveals some of the potentials within community-led efforts to re-forest when they are combined with grassroots educational programs and sustained political and economic efforts for food sovereignty.

Sankara emphasised the importance of people-powered national sovereignty for sustainable food justice. And his ground-breaking efforts to work with the people to increase awareness of the environment through incremental everyday activities and to carry out concrete programmes to foster long-term agro-ecological balance for food justice remain a powerful rubric for food justice today.

As international food aid and relief programmes move to intervene in the present famines by “dropping” millions of tons of food to provide short-term relief, we might recall Sankara’s courageous assertions that food aid is too often destructive in the long-term. His emphasis on national food sovereignty in a context of pervasive food aid shows that promoting national production and encouraging collective agro-ecology can be enormously successful in addressing the roots of hunger, even in drought-prone landscapes.

* Amber Murrey recently completed her PhD in Geography and the Environment from the University of Oxford. She teaches Development Studies at Jimma University in Jimma, Ethiopia. Amber is currently collaborating to put together an Edited Volume on Sankara’s political praxis. She can be reached at ambermurrey@gmail.com.

Notes

[1] The drought has been caused by two consecutive failed rainy seasons (aggravated by global climate change) and an ocean warming El Niňo. See Drought leaves 6 million Ethiopian children hungry, Aljazeera.

[2] Country Report for Ethiopia (2016) UNICEF Humanitarian Action for Children.

[3] Nicole Gaouette (2016) US Dispatches Emergency Aid for Ethiopian Drought. CNN Politics.

[4] Tate Munro and Lorenz Wild (2016) As Drought Hits Ethiopia Again, Food Aid Risks Breaking Resilience. The Guardian.

[5] For more systematic examinations of the cyclical production of famines, the uneven global distribution of food and contemporary issues of food justice see the work of Amartya Sen (Poverty and Famines), Tanya Kerssen (Grabbing Power), Eric Holt-Gimenez, Michael Watts (Silent Violence), Raj Patel (Stuffed and Starved), Alex de Waal (Famine Crimes) and Vandana Shiva.

[6] Mike Speir’s (1991) examination of food self-sufficiency under the Conseil National de la Rèvolution (CNR) is a notable exception. See Speir (1991) ‘Agrarian change and the revolution in Burkina Faso’. African Affairs 90(358), pp. 89-110. More recently, ABC Burkina’s Newsletter (2012) was devoted to Sankara’s ecological heritage, edited by Maurice Oudet, Director SEDELAN, see particularly Fidel Kientega’s contribution Sankarisme et l’Environnement.

[7] Here I use the Fulfulde spelling (è) thereof.

[8] Amber Murrey (2012) The Revolution and the Emancipation of Women—Thoughts on Sankara’s Speech, 25 Years Later. Pambazuka News.

[9] African countries had an estimated combined $200 billion in foreign debt in 1985, with many countries spending nearly 40 per cent of annual budgets in debt repayment. Sankara famously said in his July 1987 address at the Summit of the Organization for African Unity (OAU): ‘Africa, collectively, simply refuse to pay’.

[10] Thomas Sankara’s speech at the 39th Assembly of the United Nations General Assembly. New York: 4 Oct. 1984.

[11] Public Law (PL) 480 was signed into law as the Agricultural Trade Development Act by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on 10 July 1954.

[12] Frances Moore Lappé and Joseph Collins (2015) World Hunger: Ten Myths. In Food First Backgrounder 21(2).

[13] Oxfam International (2006) Food Aid or Hidden Dumping? Separating Wheat from Chaff. Oxfam Briefing Paper 71.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Frances Moore Lappé and Joseph Collins (2015) World Hunger: Ten Myths. In Food First Backgrounder 21(2).

[16] See Rabhi’s interview in Part 1 of Sur les traces de Thomas Sankara. Documentary film. 90 min. Burkina Faso and France: Baraka Studios.

[17] Sankara attempted to radically restructure the land regime in Burkina through the RAF or the loi portant réorganisation agraire et foncière (law on the re-organisation of agriculture and soil). The successfulness of this land paradigm, which abolished private land ownership and replaced land title with usage rights, has been questioned and criticised (see Mahmadou Zongo, 2009, ‘Terre d’etat, loi des ancêstres? Les conflits fonciers et leurs procédures de règlement dans l’ouest du Burkina Faso’ Cahiers du Cerleshs Tome XXIV(33), 1191145.

[18] The programme was implemented, as Harsch (2014, pp. 102) notes, after the unsuccessful ‘three struggles’ campaign, which had criminalised behaviours deemed unsustainable (including slash-and-burn practices, the consumption of bush meat and tree-cutting in certain areas).

[19] Harsch, pp.100.

[20] Fidel Kientega (2009) Sankarisme et Environnement. Presentation delivered at La première édition de Sankara Revival, an initiative of Musician Sams’K Le Jah. Originally in French (loose translation by author): ‘Si la justesse de certains engagements et actions de la Révolution peut être sujette à discussion, il est incontestable que du point de vue de l’environnement et de l’écologie, le Burkina aurait présenté aujourd’hui un autre visage que celui de la décrépitude et de l’option hasardeuse pour les pesticides à tout vent, les emballages plastiques qui désolent toutes nos terres et endeuillent tous nos éleveurs, les OGM au grand dam du tollé et de la désapprobation quasi-générale.’

[21] See ABC Burkina’s Newsletter (2012) devoted to Sankara’s ecological heritage, edited by Maurice Oudet, Director of SEDELAN.

[22] James Jeffrey (2016) Ethiopia Drought: How Can We Let This Happen Again? Aljazeera.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR/S AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

-found via FB. http://www.pambazuka.org/food-health...=socialnetwork

"There is great chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent."

Re: “Our stomachs will make themselves heard”: What Sankara can teach us about food justice today

Thomas Sankara

Since last January 15 a vast operation called the People’s Harvest of Forest Nurseries has been under way in Burkina with a view to supplying the 7,000 village nurseries. We sum up all of these activities under the banner of the "three battles."

Ladies and gentlemen:

I say all this not to shower unrestrained and unending praise on the modest, revolutionary experience of my people with regard to the defense of the forest and the trees, but rather to speak as explicitly as possible about the profound changes occurring in relations between man and tree in Burkina Faso. I would like to depict for you as accurately as possible the deep and sincere love that has been born and is developing between the Burkinabè man and the trees in my country.

In doing this, we believe we are applying our theoretical conceptions concretely to the specific ways and means of the Sahel reality, in the search for solutions to present and future dangers attacking trees the world over. Our efforts and those of all who are gathered here, the experience accumulated by yourselves and by us, will surely guarantee us victory after victory in the struggle to save our trees, our environment, in short, our lives.

Excellencies; Ladies and gentlemen:

I come to you in the hope that you are taking up a battle from which we cannot be absent, since we are under daily attack and believe that the miracle of greenery can rise up out of the courage to say what must be said. I have come to join with you in deploring the harshness of nature. But I have also come to denounce the one whose selfishness is the source of his neighbor’s misfortune. Colonialism has pillaged our forests without the least thought of replenishing them for our tomorrows.

The unpunished destruction of the biosphere by savage and murderous forays on the land and in the air continues. Words will never adequately describe to what extent all these fume-belching vehicles spread death. Those who have the technological means to find the culprits have no interest in doing so, and those who have an interest in doing so lack the necessary technological means. They have only their intuition and their firm conviction.

We are not against progress, but we want progress that is not carried out anarchically and with criminal neglect for other people’s rights. We therefore wish to affirm that the battle against the encroachment of the desert is a battle to establish a balance between man, nature, and society. As such, it is a battle that is above all political, one whose outcome is not determined by fate.

The establishment in Burkina of a Ministry of Water, in conjunction with our Ministry of the Environment and Tourism, demonstrates our desire to place our problems clearly on the table so that we can find a way to resolve them. We have to fight to find the financial means to exploit our existing water resources — that is to finance drilling operations, reservoirs, and dams. This is the place to denounce the one-sided contracts and draconian conditions imposed by banks and other financial institutions that preclude our projects in this area. These prohibitive conditions bring on traumatizing indebtedness robbing us of all meaningful freedom of action.

Neither fallacious Malthusian arguments — and I assert that Africa remains an underpopulated continent — nor those vacation resorts pompously and demagogically called "reforestation operations" provide a solution. We are backed up against the wall in our destitution like bald and mangy dogs whose lamentations and cries disturb the quiet peace of the manufacturers and merchants of misery.

This is why Burkina has proposed and continues to propose that at least 1 percent of the colossal sums of money sacrificed to the search for cohabitation with other planets be used by way of compensation to finance the fight to save our trees and life. While we have not abandoned hope that a dialogue with the Martians could result in the reconquest of Eden, we believe that in the meantime, as earthlings, we also have the right to reject an alternative limited to a simple choice between hell or purgatory.

Explained in this way, our struggle to defend the trees and the forest is first and foremost a democratic struggle that must be waged by the people. The sterile and expensive excitement of a handful of engineers and forestry experts will accomplish nothing! Nor can the tender consciences of a multitude of forums and institutions — sincere and praiseworthy though they may be — make the Sahel green again, when we lack the funds to drill wells for drinking water just a hundred meters deep, and money abounds to drill oil wells three thousand meters deep!

As Karl Marx said, those who live in a palace do not think about the same things, nor in the same way, as those who live in a hut. This struggle to defend the trees and the forest is above all a struggle against imperialism. Imperialism is the pyromaniac setting fire to our forests and savannah.

(From the Feb. 5, 1986 speech "Save Our Trees, Our Environment, Our Lives)

http://www.marxmail.org/quotes/thomas_sankara.htm

Since last January 15 a vast operation called the People’s Harvest of Forest Nurseries has been under way in Burkina with a view to supplying the 7,000 village nurseries. We sum up all of these activities under the banner of the "three battles."

Ladies and gentlemen:

I say all this not to shower unrestrained and unending praise on the modest, revolutionary experience of my people with regard to the defense of the forest and the trees, but rather to speak as explicitly as possible about the profound changes occurring in relations between man and tree in Burkina Faso. I would like to depict for you as accurately as possible the deep and sincere love that has been born and is developing between the Burkinabè man and the trees in my country.

In doing this, we believe we are applying our theoretical conceptions concretely to the specific ways and means of the Sahel reality, in the search for solutions to present and future dangers attacking trees the world over. Our efforts and those of all who are gathered here, the experience accumulated by yourselves and by us, will surely guarantee us victory after victory in the struggle to save our trees, our environment, in short, our lives.

Excellencies; Ladies and gentlemen:

I come to you in the hope that you are taking up a battle from which we cannot be absent, since we are under daily attack and believe that the miracle of greenery can rise up out of the courage to say what must be said. I have come to join with you in deploring the harshness of nature. But I have also come to denounce the one whose selfishness is the source of his neighbor’s misfortune. Colonialism has pillaged our forests without the least thought of replenishing them for our tomorrows.

The unpunished destruction of the biosphere by savage and murderous forays on the land and in the air continues. Words will never adequately describe to what extent all these fume-belching vehicles spread death. Those who have the technological means to find the culprits have no interest in doing so, and those who have an interest in doing so lack the necessary technological means. They have only their intuition and their firm conviction.

We are not against progress, but we want progress that is not carried out anarchically and with criminal neglect for other people’s rights. We therefore wish to affirm that the battle against the encroachment of the desert is a battle to establish a balance between man, nature, and society. As such, it is a battle that is above all political, one whose outcome is not determined by fate.

The establishment in Burkina of a Ministry of Water, in conjunction with our Ministry of the Environment and Tourism, demonstrates our desire to place our problems clearly on the table so that we can find a way to resolve them. We have to fight to find the financial means to exploit our existing water resources — that is to finance drilling operations, reservoirs, and dams. This is the place to denounce the one-sided contracts and draconian conditions imposed by banks and other financial institutions that preclude our projects in this area. These prohibitive conditions bring on traumatizing indebtedness robbing us of all meaningful freedom of action.

Neither fallacious Malthusian arguments — and I assert that Africa remains an underpopulated continent — nor those vacation resorts pompously and demagogically called "reforestation operations" provide a solution. We are backed up against the wall in our destitution like bald and mangy dogs whose lamentations and cries disturb the quiet peace of the manufacturers and merchants of misery.

This is why Burkina has proposed and continues to propose that at least 1 percent of the colossal sums of money sacrificed to the search for cohabitation with other planets be used by way of compensation to finance the fight to save our trees and life. While we have not abandoned hope that a dialogue with the Martians could result in the reconquest of Eden, we believe that in the meantime, as earthlings, we also have the right to reject an alternative limited to a simple choice between hell or purgatory.

Explained in this way, our struggle to defend the trees and the forest is first and foremost a democratic struggle that must be waged by the people. The sterile and expensive excitement of a handful of engineers and forestry experts will accomplish nothing! Nor can the tender consciences of a multitude of forums and institutions — sincere and praiseworthy though they may be — make the Sahel green again, when we lack the funds to drill wells for drinking water just a hundred meters deep, and money abounds to drill oil wells three thousand meters deep!

As Karl Marx said, those who live in a palace do not think about the same things, nor in the same way, as those who live in a hut. This struggle to defend the trees and the forest is above all a struggle against imperialism. Imperialism is the pyromaniac setting fire to our forests and savannah.

(From the Feb. 5, 1986 speech "Save Our Trees, Our Environment, Our Lives)

http://www.marxmail.org/quotes/thomas_sankara.htm

"There is great chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent."

Re: “Our stomachs will make themselves heard”: What Sankara can teach us about food justice today

Thomas Sankara: an endogenous approach to development

Oct 23, 2013

It has been thirty years since Thomas Sankara took power, before he was assassinated in 1987. The Sankarist Revolution was one of the greatest attempts at popular democratic emancipation in post-Independence Africa and is considered a novel experience of broad economic, social, cultural and political transformation

The concept of endogenous or self-centred development refers to the process of economic, social, cultural, scientific and political transformation, based on the mobilisation of internal social forces and resources and using the accumulated knowledge and experiences of the people of a country. It also allows citizens to be active agents in the transformation of their society instead of remaining spectators outside of a political system inspired by foreign models.

Endogenous development aims to mainly rely on its own strength, but it does not necessarily constitute autarky. One of the pre-eminent theoreticians of endogenous development, Professor Joseph Ki-Zerbo, states, ‘If we develop ourselves, it is by drawing from the elements of our own development.’ To put it in another manner, ‘We do not develop. We develop ourselves.’

The conception that the Professor illustrates is without a doubt inspired by his young and charismatic compatriot. In fact, the Sankarist Revolution was one of the greatest attempts at popular and democratic emancipation in post-Independence Africa. That is why it is considered a novel experience of deep economic, social, cultural and political transformation as evidenced by mass mobilisations to get people to take responsibility for their own needs, with the construction of infrastructure, (dams, reservoirs, wells, roads and schools) through the use of the principle ‘relying on one’s own strength.’

For Sankara, true endogenous development was based upon a number of principles, among them:

- The necessity of relying on one’s own strength

- Mass participation in politics with the goal of changing one’s condition in life

- The emancipation of women and their inclusion in the processes of development

- The use of the State as an instrument for economic and social transformation

These principles formed the foundation of the policies implemented by Sankara and his comrades between 1983 and 1987.

RELYING ON ONE’S OWN STRENGTH

For Thomas Sankara, relying on one’s own strength meant asking the Burkinabe people to think about their own development: ‘Most important, I think, is to give people confidence in themselves, to understand that ultimately he can sit down and write about his development, he can sit down and write about his happiness, he can say what he wants and, at the same time, understand what price must be paid for this happiness.’

The first Popular Development Plan (PPD), from October 1984 to December 1985 was adopted after a participatory and democratic process including the most remote villages. The financing of the plan was 100 percent Burkinabe. It must be noted that from 1985 to 1988, during Sankara’s presidency, Burkina Faso did not receive any foreign ‘aid’ from the West, including France, nor the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). He had relied entirely on his own strength and the solidarity of friendly countries sharing the same vision and ideals. Popular mobilisation, mainly through the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR), and the spirit of relying on one’s own forces saw 85 percent of the PPD’s objectives realised. In one year, 250 reservoirs were built and 3000 wells drilled. This does not even take into account the other achievements in the fields of health, housing, education, agricultural production, etc.

REFUSAL TO IMITATE FOREIGN MODELS

The concepts of endogenous development and relying on one’s own strength were incompatible with accepting foreign funds. ‘We categorically and definitively reject all sorts of decrees coming from foreigners.’ He also denounced ‘charlatans of all sorts who try to sell development models which have all failed.’

Sankara well understood that of which he spoke. Since independence, African states had experienced a dozen ‘development models,’ all of which had come from foreigners and were characterised by dismal failure, with exorbitant costs for the entire continent. In this regard, the 2011 Report by the Economic Commission for Africa states (p. 91): ‘The basic design and mode of implementation for all these paradigms came from outside Africa, even if each paradigm had real African disciples. It is difficult to think of other major world regions, where outside influence over the basic strategies of development is so common in recent times.’

The failure of these models confirms the old Bambaran proverb, echoed by Professor Ki-Zerbo in a book edited and published by CODESRIA, under the title, ‘Another’s Mat.’ According to the proverb, ‘Sleeping on another’s mat is like sleeping on the ground.’ This proverb explains a historic truth, a profound truth, a knowledge that a development model imposed from outside can never develop a country, much less a continent.

Relying on one’s own strength also means accepting to live within one’s means and make the best use of available resources. This guarantees dignity and freedom. President Sékou Touré of Guinea had the audacity and temerity to state this in front of General de Gaulle in 1958 in his famous phrase: ‘We prefer freedom in poverty to slavery in opulence.’

Thomas Sankara endorsed the creed of the great Guinean orator and rephrased President Touré’s words to a simpler and more straightforward: ‘Accept living as Africans. That is the only way to live with freedom and dignity.’

But ‘to live with freedom and dignity,’ one must be able to feed themselves and not rely on begging throughout the international community. For a country which cannot feed itself inevitably risks losing its independence and dignity. Sankara famously questioned: ‘Where is imperialism? Look at your plates when you eat. The imported rice, maize and millet; that is imperialism.’ To avoid this, Sankara insisted: ‘Let us try to eat what we control ourselves.’

It was to achieve this goal that he mobilised the Burkinabe farmers to attain food self-sufficiency which in turn strengthened the confidence and dignity of the Burkinabe people. Former UN Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Jean Ziegler, said that this result was achieved by a massive redistribution of land to rural inhabitants combined with supplying fertilizers and irrigation.

Today, Sankara’s spirit animates African farmers who are struggling to achieve food sovereignty by transforming their local resources and guarding their food from GMOs that Western multinationals wish to dump in our markets.

But ‘living free’ also involves re-evaluating local resources to meet the needs of the population. This is why Sankara particularly emphasised the need to transform the cotton produced in Burkina Faso into clothing for the people. The famous ‘Faso dan Fani’, the local garment, was an example of this transformation of the cotton for the domestic market. Sankara made an impassioned plea for wearing the ‘Faso dan Fani’ at the OAU Summit; advocacy which was greeted with applause from African Heads of State.

Living free also means to avoid the pitfalls and humiliations of the supposed ‘development aid’ which has contributed to the under-development of Africa and its dependency. As Sankara states: ‘Of course, we encourage everyone to help us eliminate aid. But in general, aid policies leave us disorganised, by undermining our sense of responsibility for our own economic, political and cultural affairs. We have taken the risk of borrowing new ways to realise our own well-being.’

LIBERATING WOMEN AND MAKING THEM CENTRAL ACTORS IN DEVELOPMENT

Another stroke of genius by Sankara was to have understood that real development would be impossible without the liberation of all oppressed groups, starting with women. In this regard, he said: ‘We cannot transform society while maintaining domination and discrimination against women, who comprise more than half our society…Our revolution has worked for three and a half years to progressively eliminate demeaning practices towards women…Also they must be engaged as Burkinabe producers and consumers…Together we must always ensure access of women to work. This emancipatory and liberating work will ensure women’s economic independence, a greater social role and a more just and complete knowledge of the world.’

In effect, development, like economic, social, political and cultural processes, cannot become a reality without the total emancipation of women, the end of all forms of discrimination against them and their active participation in the process of transformation. Once again Sankara was ahead of his African peers and even some Western leaders and international institutions.

Today, at the United Nations, the most conservative states are loudly celebrated for their ‘liberation’ of women, a liberation which is often more illusory than real. The struggle for the liberation of women has become a common one, with the creation of UN Women, parity laws and other measures aimed at women’s economic, social and political emancipation or empowerment. Once again, history demonstrates the prescience and strategic vision of Sankara, who was far ahead of his time.

IDENTIFYING WITH POLULAR MASS ASPIRATIONS

For Sankara, being a revolutionary meant giving priority to the basic needs of the urban and rural masses. He attempted to reach their level in order to fully understand and marry their cause, which was a source of conflict with the fringes of the urban petty bourgeoisie who would not renounce their ‘privileges.’ For him, ‘we do not participate in a revolution to simply replace the old potentates with others. We do not participate in the revolution because of a vindictive motivation.’ ‘Get out of there so I can install myself.’ This kind of movement is alien to the revolutionary ideal of August and those who display it demonstrate their flaws as petty bourgeois opportunists and dangerous counter-revolutionaries.

It was in opposition to these urban petty bourgeois that Thomas Sankara, in line with Amilcar Cabral called on intellectuals to ‘commit suicide’ to be reincarnated as ‘revolutionary workers’ in the service of the people. Cabral said: ‘the revolutionary petty bourgeoisie must be able to commit suicide as a class to be reincarnated as revolutionary workers identifying completely with the deep aspirations of the people to which they belong.’

It is true that Sankara tried to instill a different mentality in the petty intellectual bourgeoisie. Unfortunately, they were quicker to repeat revolutionary slogans than to change their behaviour and lifestyle. In fact, this is one of the major challenges to any economic and socially transformative movement in African countries. Indeed, a number of intellectual ‘revolutionaries,’ once in power, tend to turn their backs on people and almost everywhere, they engage in the pursuit of money and privilege at the expense of the struggle for the decolonisation of the mind and the transformation of economic and social structures inherited from colonialism.

Decolonisation is understood in the sense of Fanon, who stated: ‘Decolonisation, as we know, is a historical process. Decolonisation never takes place unnoticed, for it influences individuals and modifies them fundamentally. It transforms spectators crushed with their inessentiality into privileged actors, with the grandiose glare of history’s floodlights upon them. In decolonisation, there is therefore the need of a complete calling into question of the colonial situation.’

This is the fundamental objective of Thomas Sankara. But he encountered the forces of inertia, such as the Westernised petty bourgeoisie, which constitutes an obstacle to any political rupture aimed at changing society, and the structures inherited from colonialism. It is this inertial force which explains in part the failure of the leftist parties in Africa, notably in ‘francophone’ countries. It is this obstacle which finally undermined the revolution in Burkina Faso and helped to create the conditions which led to the assassination of Thomas Sankara on 15 October, 1987.

THE STATE AS AN INSTRUMENT FOR ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION

Sankara was a communist and had a great admiration for socialist regimes, including Cuba, which filled him with respect and pride. He recognised that the state was central to successful transformations in these countries. He also knew that a state just emerging from the long and terrible colonial darkness could not rebuild without active and committed leadership. So, for him, the state must be central in the process of economic, social and cultural transformation. It was under the leadership of the state and its institutions that the masses were mobilised to participate in the first PPD.

But, after his assassination, when Burkina Faso knelt before the World Bank and the IMF, the state was vilified and stripped of its basic functions for the benefit of foreign capital, with consequences which we well know. The decline of the state led to the deterioration of living standards, as is common in other African countries.

The failures of structural adjustment programs (SAP) and the collapse of market fundamentalism requires the re-emergence of the state. It is in this context that Cea (2011) and UNCTAD (2007) urged African countries to build developmental states in order to become active agents in development, like the Asian ‘Tigers’ or ‘Dragons’ and the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

SOLIDARITY AGAINST THE SERVITUDE AND LOOTING CAUSED BY DEBT

On the eve of the foundation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, which later became the African Union (AU) in 2001, Kwame Nkrumah, first President of Ghana, visionary leader and figurehead of the Pan-African revolution, said: ‘Africa must unite or perish’!

Indeed, faced with powerful and well organised enemies who wish to continue their domination of Africa in order to plunder its riches, only solidarity and unity can help Africa preserve its independence. A fervent Pan-Africanist and admirer of the great Ghanaian leader, Thomas Sankara endorsed this statement of truth by President Nkrumah. That is why Sankara, participating in his last summit in Addis Ababa in July 1987, had shouted at African leaders asking them to form a united front to demand the cancellation of illegitimate African debt. Because, he said, ‘debt in its current form is a cleverly organised re-conquest of Africa, that its’ growth and development conform to standards and levels which are totally foreign. It ensures that each of us becomes a financial slave, meaning a slave for those who had the opportunity, cunning, and deceit to invest their funds in us with the obligation that we repay. The debt can never be repaid since if we refuse to pay it our lenders will not die. Of that we can be certain. Yet if we do pay it is us who will die. Of that we can be equally certain.’

Burkina Faso is part of a group of more than thirty African states called ‘Least Developed Countries’ (LDCs). According to UNCTAD (2010) in the LDCs, 6 out of 10 people live on the equivalent of $1.25 a day and nearly 9 in 10, 88 percent live on the equivalent of $2 a day! This means that these countries need to retain all their resources to put in the service of development. Every penny that comes out of these countries in the form of debt service or the repatriation of profits would be detrimental to the well-being of their people. This is why Sankara was right to say that ‘if we do pay it we will die.’

Always connected to the external debt of the continent, Thomas Sankara was one of the few African leaders, if not the only, to have criticised and rejected the adjustment policies of the World Bank and IMF, which have increased the debt burden and impoverished African countries. His government refused any form of collaboration with these institutions and rejected their ‘help.’ He developed and implemented his own self-adjustment program, which had been supported by the people who understood the merits of his policies and the sacrifices required of all, both citizens and leaders.

THE STRUGGLE FOR ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION

A visionary, Sankara understood before many others, including the so-called developed world, the importance of the environment as an essential fact to the survival of Humanity. Millions of trees were planted in order to stop desertification. Every event, baptism, marriage, was an opportunity to plant trees. This led to a massive mobilisation of people who understood the meaning and scope of such a decision: to build a country with their own hands! This is the key idea behind the vision of Thomas Sankara.

He had understood very early to economic and social costs his country might incur as a result of environmental degradation. That is why one of the main pillars of his development policy was mobilising people to protect their environment.

Sankara understood the link between the mode of capitalist production and consumption to environmental degradation: ‘The struggle for the trees and the forest is the anti-imperialist struggle. Imperialism is the arsonist of our forests and our savannahs.’

The current damage caused by climate change due to greenhouse gas emissions, resulting from capitalist countries production and consumption, have confirmed Sankara’s predictions. However his country and the rest of Africa, which contribute less to the global degradation by emitting low amounts of greenhouse gases, may yet pay a high price.

IN CONCLUSION

- Undoubtedly, Thomas Sankara was a visionary, a charismatic leader and a true revolutionary. This is why he left an indelible mark on the collective consciousness of the African people and his actions have also had a profound resonance beyond Africa.

- He was ahead of his time. Currently, all the issues at the heart of his struggle are central to national and international debates: the liberation of women, debt, food sovereignty, solidarity between African states, South-South solidarity, protection of the environment, etc.

- The African Union and other continental institutions seeking to build a new development paradigm designed and implemented by Africans themselves. This was the central axis of Sankara’s, and some of his illustrious predecessors, struggles.

- Of course, like any human endeavours, Sankara’s were imperfect. It is questionable in many aspects.

- But what is certain is that it has shown the path to a possible Alternative Development, based upon popular mobilisation and self-confidence in the face of imported ideas and models. Undoubtedly, it is a difficult road, but the only way to “live free and dignified”.

- Sankara embraced the ideas and struggles of his illustrious predecessors, while others are in the process of adopting his ideas and struggles, which are more relevant than ever, since, ‘you cannot kill ideas,’ as he said in a speech in memory of Che Guevara, a week before his assassination.

- Thomas Sankara is physically gone, but his ideas and example will continue to inspire other Africans to continue the struggle and ideas for which he gave his life.

- In this sense, Sankara is not dead! He lives in each and every one of us!

https://www.pambazuka.org/pan-africa...ch-development

Oct 23, 2013

It has been thirty years since Thomas Sankara took power, before he was assassinated in 1987. The Sankarist Revolution was one of the greatest attempts at popular democratic emancipation in post-Independence Africa and is considered a novel experience of broad economic, social, cultural and political transformation

The concept of endogenous or self-centred development refers to the process of economic, social, cultural, scientific and political transformation, based on the mobilisation of internal social forces and resources and using the accumulated knowledge and experiences of the people of a country. It also allows citizens to be active agents in the transformation of their society instead of remaining spectators outside of a political system inspired by foreign models.

Endogenous development aims to mainly rely on its own strength, but it does not necessarily constitute autarky. One of the pre-eminent theoreticians of endogenous development, Professor Joseph Ki-Zerbo, states, ‘If we develop ourselves, it is by drawing from the elements of our own development.’ To put it in another manner, ‘We do not develop. We develop ourselves.’

The conception that the Professor illustrates is without a doubt inspired by his young and charismatic compatriot. In fact, the Sankarist Revolution was one of the greatest attempts at popular and democratic emancipation in post-Independence Africa. That is why it is considered a novel experience of deep economic, social, cultural and political transformation as evidenced by mass mobilisations to get people to take responsibility for their own needs, with the construction of infrastructure, (dams, reservoirs, wells, roads and schools) through the use of the principle ‘relying on one’s own strength.’

For Sankara, true endogenous development was based upon a number of principles, among them:

- The necessity of relying on one’s own strength

- Mass participation in politics with the goal of changing one’s condition in life

- The emancipation of women and their inclusion in the processes of development

- The use of the State as an instrument for economic and social transformation

These principles formed the foundation of the policies implemented by Sankara and his comrades between 1983 and 1987.

RELYING ON ONE’S OWN STRENGTH

For Thomas Sankara, relying on one’s own strength meant asking the Burkinabe people to think about their own development: ‘Most important, I think, is to give people confidence in themselves, to understand that ultimately he can sit down and write about his development, he can sit down and write about his happiness, he can say what he wants and, at the same time, understand what price must be paid for this happiness.’

The first Popular Development Plan (PPD), from October 1984 to December 1985 was adopted after a participatory and democratic process including the most remote villages. The financing of the plan was 100 percent Burkinabe. It must be noted that from 1985 to 1988, during Sankara’s presidency, Burkina Faso did not receive any foreign ‘aid’ from the West, including France, nor the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). He had relied entirely on his own strength and the solidarity of friendly countries sharing the same vision and ideals. Popular mobilisation, mainly through the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR), and the spirit of relying on one’s own forces saw 85 percent of the PPD’s objectives realised. In one year, 250 reservoirs were built and 3000 wells drilled. This does not even take into account the other achievements in the fields of health, housing, education, agricultural production, etc.

REFUSAL TO IMITATE FOREIGN MODELS

The concepts of endogenous development and relying on one’s own strength were incompatible with accepting foreign funds. ‘We categorically and definitively reject all sorts of decrees coming from foreigners.’ He also denounced ‘charlatans of all sorts who try to sell development models which have all failed.’

Sankara well understood that of which he spoke. Since independence, African states had experienced a dozen ‘development models,’ all of which had come from foreigners and were characterised by dismal failure, with exorbitant costs for the entire continent. In this regard, the 2011 Report by the Economic Commission for Africa states (p. 91): ‘The basic design and mode of implementation for all these paradigms came from outside Africa, even if each paradigm had real African disciples. It is difficult to think of other major world regions, where outside influence over the basic strategies of development is so common in recent times.’

The failure of these models confirms the old Bambaran proverb, echoed by Professor Ki-Zerbo in a book edited and published by CODESRIA, under the title, ‘Another’s Mat.’ According to the proverb, ‘Sleeping on another’s mat is like sleeping on the ground.’ This proverb explains a historic truth, a profound truth, a knowledge that a development model imposed from outside can never develop a country, much less a continent.

Relying on one’s own strength also means accepting to live within one’s means and make the best use of available resources. This guarantees dignity and freedom. President Sékou Touré of Guinea had the audacity and temerity to state this in front of General de Gaulle in 1958 in his famous phrase: ‘We prefer freedom in poverty to slavery in opulence.’

Thomas Sankara endorsed the creed of the great Guinean orator and rephrased President Touré’s words to a simpler and more straightforward: ‘Accept living as Africans. That is the only way to live with freedom and dignity.’

But ‘to live with freedom and dignity,’ one must be able to feed themselves and not rely on begging throughout the international community. For a country which cannot feed itself inevitably risks losing its independence and dignity. Sankara famously questioned: ‘Where is imperialism? Look at your plates when you eat. The imported rice, maize and millet; that is imperialism.’ To avoid this, Sankara insisted: ‘Let us try to eat what we control ourselves.’

It was to achieve this goal that he mobilised the Burkinabe farmers to attain food self-sufficiency which in turn strengthened the confidence and dignity of the Burkinabe people. Former UN Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Jean Ziegler, said that this result was achieved by a massive redistribution of land to rural inhabitants combined with supplying fertilizers and irrigation.

Today, Sankara’s spirit animates African farmers who are struggling to achieve food sovereignty by transforming their local resources and guarding their food from GMOs that Western multinationals wish to dump in our markets.

But ‘living free’ also involves re-evaluating local resources to meet the needs of the population. This is why Sankara particularly emphasised the need to transform the cotton produced in Burkina Faso into clothing for the people. The famous ‘Faso dan Fani’, the local garment, was an example of this transformation of the cotton for the domestic market. Sankara made an impassioned plea for wearing the ‘Faso dan Fani’ at the OAU Summit; advocacy which was greeted with applause from African Heads of State.

Living free also means to avoid the pitfalls and humiliations of the supposed ‘development aid’ which has contributed to the under-development of Africa and its dependency. As Sankara states: ‘Of course, we encourage everyone to help us eliminate aid. But in general, aid policies leave us disorganised, by undermining our sense of responsibility for our own economic, political and cultural affairs. We have taken the risk of borrowing new ways to realise our own well-being.’

LIBERATING WOMEN AND MAKING THEM CENTRAL ACTORS IN DEVELOPMENT

Another stroke of genius by Sankara was to have understood that real development would be impossible without the liberation of all oppressed groups, starting with women. In this regard, he said: ‘We cannot transform society while maintaining domination and discrimination against women, who comprise more than half our society…Our revolution has worked for three and a half years to progressively eliminate demeaning practices towards women…Also they must be engaged as Burkinabe producers and consumers…Together we must always ensure access of women to work. This emancipatory and liberating work will ensure women’s economic independence, a greater social role and a more just and complete knowledge of the world.’

In effect, development, like economic, social, political and cultural processes, cannot become a reality without the total emancipation of women, the end of all forms of discrimination against them and their active participation in the process of transformation. Once again Sankara was ahead of his African peers and even some Western leaders and international institutions.

Today, at the United Nations, the most conservative states are loudly celebrated for their ‘liberation’ of women, a liberation which is often more illusory than real. The struggle for the liberation of women has become a common one, with the creation of UN Women, parity laws and other measures aimed at women’s economic, social and political emancipation or empowerment. Once again, history demonstrates the prescience and strategic vision of Sankara, who was far ahead of his time.

IDENTIFYING WITH POLULAR MASS ASPIRATIONS

For Sankara, being a revolutionary meant giving priority to the basic needs of the urban and rural masses. He attempted to reach their level in order to fully understand and marry their cause, which was a source of conflict with the fringes of the urban petty bourgeoisie who would not renounce their ‘privileges.’ For him, ‘we do not participate in a revolution to simply replace the old potentates with others. We do not participate in the revolution because of a vindictive motivation.’ ‘Get out of there so I can install myself.’ This kind of movement is alien to the revolutionary ideal of August and those who display it demonstrate their flaws as petty bourgeois opportunists and dangerous counter-revolutionaries.

It was in opposition to these urban petty bourgeois that Thomas Sankara, in line with Amilcar Cabral called on intellectuals to ‘commit suicide’ to be reincarnated as ‘revolutionary workers’ in the service of the people. Cabral said: ‘the revolutionary petty bourgeoisie must be able to commit suicide as a class to be reincarnated as revolutionary workers identifying completely with the deep aspirations of the people to which they belong.’

It is true that Sankara tried to instill a different mentality in the petty intellectual bourgeoisie. Unfortunately, they were quicker to repeat revolutionary slogans than to change their behaviour and lifestyle. In fact, this is one of the major challenges to any economic and socially transformative movement in African countries. Indeed, a number of intellectual ‘revolutionaries,’ once in power, tend to turn their backs on people and almost everywhere, they engage in the pursuit of money and privilege at the expense of the struggle for the decolonisation of the mind and the transformation of economic and social structures inherited from colonialism.

Decolonisation is understood in the sense of Fanon, who stated: ‘Decolonisation, as we know, is a historical process. Decolonisation never takes place unnoticed, for it influences individuals and modifies them fundamentally. It transforms spectators crushed with their inessentiality into privileged actors, with the grandiose glare of history’s floodlights upon them. In decolonisation, there is therefore the need of a complete calling into question of the colonial situation.’