From Harvard to Karl-Marx-Allee: The Experiences and Reflections of an American Communist in East Germany

From Harvard to Karl-Marx-Allee: The Experiences and Reflections of an American Communist in East Germany

By Zhao Dingqi, Victor Grossman (Posted Apr 23, 2024)

Zhao Dingqi: What things did you experience in your early years that have converted you to a Communist? What did you do in America after you became a Communist?

Victor Grossman: Born in 1928 in New York, a left-leaning city in a left-leaning era, I grew up during the bitter, hungry years of the Great Depression of the 1930s, a time when Communist unions and leftist organizations were hitting back hard, leading in creating a powerful labor movement, winning jobless insurance, pensions, a limited work week and the right to join unions, and greatly affecting all of society and culture. Communists also led in early battles to end racist oppression and work for Black-white unity. All such actions—and my leftist parents—made me into what was called a “red-diaper baby.”

I joined the Young Communist League at high school during the Second World War and, at 17 years old, at Harvard College, the Communist Party. I was just a few months too young to get drafted into the army in 1945, when the war ended and, with it, the U.S.-USSR alliance. Our little group (thirty members at its peak) was more or less secret but very active. We picketed to end racial discrimination against Black people in a student pub and against “whites only” hiring at a Boston department store. We opposed U.S. support for Francisco Franco’s fascist government in Spain and demonstrated against the Harry S. Truman government’s Cold War use of its early atomic bomb monopoly to control the world while breaking the militancy of the union movement. We joined in a campaign for a peace-based new Progressive Party backing former Vice President Henry Wallace in the election of 1948. The right-wing forces proved far too strong, however, and won many years of full control of U.S. policy at home and abroad. But our little group, including some of the most brilliant students at Harvard, kept up our actions, debating questions of Marxism and strategy, organizing concerts with left-wing singers like Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, but also joking, flirting and singing a lot ourselves—including even “Chee Lai” (in English, with one verse in Chinese), not yet an anthem, which we learned from the great Black singer and actor Paul Robeson. We moved pins on a big map of China, rejoicing at every Liberation Army advance.

When about ten of us got our diplomas in 1949, our Communist Party secretary in Boston asked if any of us, despite prestigious Harvard diplomas, would consider becoming workers in factories, in an attempt to rescue the labor movement from the corrupt right-wingers then taking over. Three of us agreed, and I became a low-paid, unskilled metal-worker in a factory in Buffalo, a completely new world for me.

Most of my fellow workers were pious, racist, and often conservative. But I also found that most of them were forced by circumstances to be very class-conscious; not intellectually, like my fellow Communists at Harvard, but very clearly so in their daily battle against being exploited by the company, a fight for worktime minutes and piecework dollars and cents, with the company doing everything it could to set one group against the other: late shift against early shift, piece workers against hourly workers, old against young workers, with women and the few Black workers at the bottom of the pile.

For three “probation” months, during which the company could fire me arbitrarily, I refrained from any political activity. After that I became active, and discovered the wonderful home of the African-American Lumpkin family. After moving north from dangerously racist Florida, one of the family’s ten children discovered the Communist movement, in which Black and white joined hands in equality and friendship. Before long, she had recruited her parents and most of her nine siblings, some with spouses, and their rickety wooden house became the center of leftists in Buffalo—and soon became my “home away from home.” I started selling our party newspaper door-to-door, I joined in collecting signatures for the Stockholm Peace Appeal, which stated:

“We demand the outlawing of atomic weapons as instruments of intimidation and mass murder of peoples.… We believe that any government which first uses atomic weapons against any other country whatsoever will be committing a crime against humanity and should be dealt with as a war criminal.”

It was signed by well over 200 million people worldwide—a large proportion in the USSR and China—but was attacked by the U.S. media and government. This meant that I only dared to gather signatures and sell our newspaper in Black neighborhoods, where dangerously prevalent anti-Communist feelings were rare. In one of our actions, opposing the “whites only” sale of tickets to a boat cruise on Lake Erie, I witnessed the brutal beating, arrest, and near shooting of one of our group, one of the Lumpkin family. In general, in my time in Buffalo, while I could accomplish very little in those increasingly brutal and oppressive years, I learned very much about the thinking and feelings of my white fellow workers, and about the perils of life in the Black ghettos—joblessness, miserable housing, the spread of drugs, police brutality. I also learned—much, much later—that the Federal Bureau of Investigation was closely monitoring whatever I did and said, in Buffalo and even before that at Harvard.

ZD: During McCarthyism, why did you choose to leave the U.S. military to live in East Germany?

VG: In June 1950, the Korean War began, and with it, an intense increase in anti-Communist hysteria and hatred. After a five-year break, young American men would again be drafted, put in uniform and sent overseas. I would no longer be learning how to push a cartload of copper rolls or unload steel plate from a crane, but rather how to salute, march, load, aim, and fire a rifle. I was ordered to show up in January 1951. I quit my job and returned to New York City, where I had not been active since high school days, and hoped I was politically unknown. I was faced by two major problems: How could I ever shoot at North Korean or Chinese soldiers? How would I be able to avoid doing so?

But a far more immediate question was: Should I sign the required statement that “I was not and had never been a member” of any Communist or Communist-related organization? I was or had been in a dozen, including the Spanish Refugee Relief Fund, the Southern Negro Youth Congress (I had joined with a $1 solidarity contribution), the Sam Adams School on Marxism, the youth organizations previously mentioned, and the Communist Party itself. According to the McCarran Law of 1950, I should have reported such membership to the police as a “foreign agent.” For non-compliance, one could be imprisoned for up to five years for every single day of non-compliance (plus a $10,000 fine). Neither I nor anyone else ever complied with this insanity and in 1965, it was ruled unconstitutional. But this was 1951! Should I admit my memberships? Out of pure fear I signed the paper, concealing the awful truth in hopes that no one would check up during my two years of service.

After I had signed, received a uniform, a hard hat, and first rules, and after the Black draftees were separated out and sent to the Deep South, we white draftees landed in a camp in Virginia, also in the segregated South. (In Richmond, on our first free day there a few months later, I saw for the first time the separation in buses which still prevailed in 1951: white people in the front and Black people in the back, even when seats were free only in the front.)

After our training was complete we were divided into two groups; one was sent to fight in Korea. Mine—very, very luckily—was sent to be Occupation soldiers in West German Bavaria. I risked taking a three-month course as a radio operator, which meant learning the Morse Code and enabled me to travel on weekends to many interesting cities: Munich, Hamburg, Nuremberg. I went on a ten-day furlough to Italy and, not in uniform there, joined in the joint, then still allied Communist-Socialist parade and celebration, marching and singing along in the most wonderful May Day celebration in my entire life.

However, shortly afterwards, with only five months left in my service time, my world was turned upside down. I received a registered letter from the legal offices of the U.S. Army in Washington, naming seven organizations I had belonged to but not reported when I signed that statement. I was ordered to report six days later to a U.S. military judge in Nuremberg. I knew the punishment for concealing such memberships—in other words, perjury—could be up to five years in a military prison: in those days of hysteria that might even be physically dangerous. I certainly did not want to abandon, perhaps forever, my home country and the fight to make it better and peaceful while outlawing exploitation, racism, and poverty. But I definitely did not want to land behind steely GI prison bars; therefore, I made the decision to desert or, as I saw it: I chose freedom! The place I decided upon for this choice was unusual; in 1952, the dividing line between the U.S. and Soviet zones of Austria, in the city of Linz, was formed by the Danube River. That is where, after throwing my shoes, jacket, and new camera into the rushing water, I swam across from one world to the other.

After spending several hours vainly searching for Red Army bunkers, tanks, or other defenses of the “Iron Curtain,” I was picked up by Austrian policemen and brought, as I demanded, to the local Soviet command post. The next day I was lodged for two weeks in a cell in their Austrian headquarters—enough time to wonder at length about what my fate would be. But then I was given a complete new set of clothes, from hat to shoes (“with a red tie!”) and taken north across Czechoslovakia to the (East) German Democratic Republic (GDR), where I assumed a new name, Victor Grossman, which I agreed upon in order to save my family from difficulties on my account. On Election Day 1952, the day Dwight Eisenhower was elected U.S. president, I began my own completely new life in a middle-sized town in Saxony, for the first weeks in a hotel, then in a furnished room with a friendly family.

ZD: Could you talk about your life in East Germany? How was it different from West Germany and the United States? How did the East German people generally think of their life? Did they live happily in East Germany?

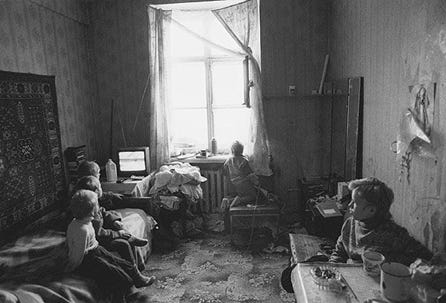

VG: I knew that little East Germany, badly wrecked and lacking in almost all natural resources except low-grade lignite coal, was still almost single-handedly paying postwar reparations to Poland and the USSR, which German armies had devastated, causing the death of six million Poles and twenty-seven million Soviet citizens. But when I arrived, only seven years after a war which had also hit this town of Bautzen, East Germany, I saw none of the hungry, ragged people I might have expected from reading Western media; the shops and restaurants offered quite enough staple foodstuffs and basic goods. However, there were always gaps and the assortment was still Spartan. Bus service had not yet begun; among the few vehicles on the streets, I saw delivery trucks with two wheels in back and one in front and some cars mounted with woodburning motors. Many evenings, always unexpectedly, there would be a sudden power cut; it was necessary to always have matches and candles near at hand. In most apartments built before the war, there was no central heating and often no flush toilet. But I did not grumble; I supported the basic goals now being announced and in general, despite all problems, daily life seemed quite normal.

For five months, I worked at a large factory, in a small team carrying long planks of oak and beech to be sawed up for use in making railroad cars. This fairly hard work gave me a chance to compare it with my work in Buffalo. Most notable for me was that every day there was a substantial warm lunch in the canteen, run by the union at a very low price. Since lunch is the main meal of the day in Germany, with only light breakfasts and suppers, I was saved from most shopping and all cooking. In Buffalo, nothing had been offered but a cigarette machine. Another difference: in Buffalo, I was given one week of vacation; after three years this would increase to two weeks, but only if I stayed with the same company. In the GDR there was an annual vacation for everyone, for at least three weeks even if one changed jobs. And here if needed I could visit the factory doctor during work time; even shopping was possible in the factory cooperative shop. If imported items were available, such as lemons or raisins (still very rare in the town shops) or fresh cherries, strawberries, or tomatoes, at least one team member would hop over for all the others, on company time. Sometimes the whole team would join the line. In general, there was a more relaxed atmosphere, with no conflict between workers and foremen, partly because no one feared being fired and job openings were everywhere. (Moreover, evictions from homes were forbidden by law.) A minor advantage: wages were paid in cash in those days, not like in the United States, where they were paid by check (which often meant a loss when cashing them).

I left that job and became an apprentice, learning (to my own amazement as a technical imbecile) how to operate a lathe. Later, I was able to go to college again, four years at the Journalism School of the Karl Marx University in Leipzig, a city of half a million inhabitants—so very welcome to me, as a New Yorker. The school was different in many ways from Harvard; new students were divided into groups of about twenty-five who stayed together, not only for the same lectures and seminars during the first two years but also for visits to the movies or theater, self-made evenings devoted to some writer or artist, sports (volleyball and table tennis), and also “political life”—many meetings, a few parades, and now and again semivolunteer work, like helping new cooperative farms with sugar-beet weeding or potato harvesting, clearing the last remaining wartime rubble, building a big new soccer stadium or once, for a week, helping to stabilize tracks in a giant open pit coal mine. Despite muscle pains, I enjoyed these chances to meet farm people, construction workers, and miners.

As I sensed then—and found confirmed later—that the curriculum was under the influence of two different forces. The Agit-Prop Department of the Socialist Unity Party (also known as SED), the dominant force among the five political parties in the GDR, stressed the training of political journalists to convince and win more of the population to support party policies, the GDR, and socialism. The Education Ministry, without contesting this aim, wanted more stress on training journalists who could write well and had a broad literary and cultural background. We had professors and lecturers from both sides. The stress on agitation and propaganda in the GDR media had far too often had exactly the opposite effect than the one intended. Often dull and repetitive, it commonly turned people off. As for me, I learned relatively little about good journalism methods (that came later, while working with an expert journalist). But I was lucky to have a very good professor on German history and an even better one on the wealth of German literature—till then both largely unknown to me.

Of course, there was one major difference between the GDR and the United States: tuition charges at Harvard, plus meals, dormitory, medical, and other charges were still very low when I attended; under $1,000 a year. Despite a $500 scholarship (if I kept at least a B average), this was still tough for me. Today, yearly tuition has soared to nearly $60,000. In the GDR, all colleges (for me and both sons) charged nothing, offered both food and lodging at very low cost, plus enough monthly assistance to cover all living costs, making jobbing unnecessary and student debt unknown.

My four years of study and my very lucky, happy marriage (and the birth of our first son) completed my integration into GDR daily life and thinking. The Soviet Occupation authorities and the largely Communist or left-wing Social Democrats who became leaders in founding and shaping this new state found a population whose fanatic devotion to Adolf Hitler had been largely replaced (though not 100 percent) by a cynical rejection of all ideology, with not all too many recalling and reviving long suppressed or abandoned left-wing dreams and hopes. Gradually, over the years, it became possible to win over, or at least push toward neutrality, a sector of the population for a policy opposed to a capitalist society ruled by the same giant companies which built up Hitler and swallowed giant wartime profits from the extreme exploitation of forced laborers from occupied Europe, prisoners of war and concentration camp slaves. At first, many were bitter about violence committed by some Soviet troops during the first few weeks, including many cases of rape. But after learning of the mass horrors committed by the Nazi armies in the Soviet Union and Poland, more and more people overcame hatred and resentment, and became aware of Soviet attempts to care for the hungry, especially the children; to re-open schools and communication; and to revive theater, cinema, and other arts. Among the results were some magnificent antifascist plays, books, and films.

It was a society full of changing, complicated crosscurrents. Among the citizens were a growing number who favored and became endeared to the construction of a society not based on greed and profit and were loyal to the GDR. There were others who still craved a return to the regions in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and elsewhere that they were forced to leave by decision of the four victorious powers. Some were motivated by an innate hatred of everything Russian, Communist or socialist. There were also hypocrites and careerists with no other ideology than gaining higher positions for themselves. There were also some at various levels of leadership who sincerely believed in a socialist goal but were so dogmatic that they considered any other views than their official ones, even the most constructive criticism, as “hostile western propaganda.”

However, there was indeed plenty of genuinely hostile Western propaganda, big gobs of it from the very start. Those giant companies wanted their factories back again! From the start, there was a constant barrage of extremely clever U.S., British, and West German propaganda via radio and in publications available until 1961 in West Berlin, located in the middle of the GDR, and later through “West TV,” visible almost everywhere in the GDR and always trying to divide and win over its population. The main method was to demonstrate how far ahead the capitalist West was, with its fashionable clothing; modern appliances; swift, racy cars; and exciting tours in all the world. Also, of course, how much freedom there was in “the West” (except for the Communists, whose party was repressed and then forbidden in 1956). For young people, there were the latest music waves, and sly jokes were a regular part of the weapon assortment.

One crafty joke involved China: During an official state visit, GDR premier Otto Grotewohl asked Mao Zedong “Say, Mao, you have achieved so amazingly much here. But certainly, there are some who still oppose party policies. How many, do you estimate?” ”Well, Otto,” was the answer, “Just between us, we think there are still about 16–17 million.” To which Grotewohl replied: “Really? Not much different than with us!” (GDR population at the time was 17 million).

This joke, though greatly exaggerated, did contain a little too much truth. In March 1952, Joseph Stalin had proposed the formation of a united, democratically elected German state, free of occupation troops but, like Austria and Finland, with no ties to any military pacts. Such unity was quickly rejected by both West Germany and the United States, thus forcing the little GDR to build its own new industrial base, one now openly aiming at socialism. In taking on this very difficult task, it made many errors and alienated too many people. In June 1953, thousands of mostly working people, beginning with East Berlin construction crews at the big Stalin Allee site, revolted against many tough measures, especially at increased work quotas aiming at higher productivity. Joining the protests were also tough, young right-wingers who came over from West Berlin and helped set kiosks and one department house building on fire. The CIA-sponsored radio station in West Berlin egged on the protests and spread calls for a general strike. Most people did not join in and the protests were contained within a few days with the help of Soviet troops and tanks, but this critical event ushered in many important changes: reparation payments to the USSR ended, repressive measures were reversed, tougher work quotas reduced, electricity shutdowns for homes barred, and major attempts initiated to improve living standards in every way. More and more people could now buy refrigerators, washing machines, TV sets, and more attractive clothing—and to improve the garden or weekend bungalows that so many GDR citizens maintained in the countryside.

There were more ups and downs in the GDR, often determined by events in the outside world, in West Germany and especially in the USSR, where Stalin had been followed by Nikolai Khrushchev, who was replaced by Leonid Brezhnev. Each one embraced different policies regarding relations with the GDR, where it still maintained large numbers of troops. Most famous of all, at a time of extreme Cold War tension, was the building of the “Berlin Wall” in August 1961, thus ending the uncontrolled exchange of people and publications between East and West in the divided city and thus, in all of Germany—an extremely unhappy act but one which President John F. Kennedy described as “not a very nice solution, but a Wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.”

Perhaps surprisingly, however, after the wall fell, the large-scale West German brain-drain of the economy of the GDR began to improve much more vigorously than ever before. The standard of living kept rising, many new factories were built, and, despite an ever more heated propaganda campaign from the West, with every form of pressure on relatives, experts, and professionals in the GDR, its government, led by the Socialist Unity Party, achieved the highest degree of popularity in its entire existence—estimated at about 70 percent, no small achievement after Germany’s bitter past.

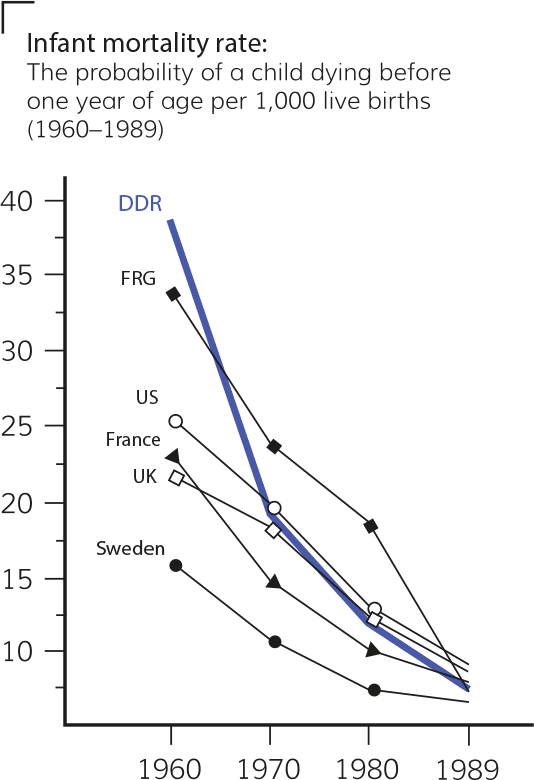

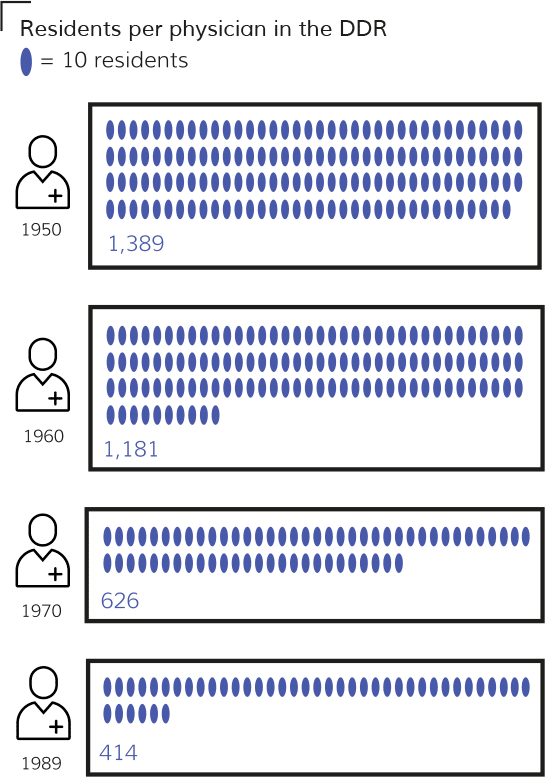

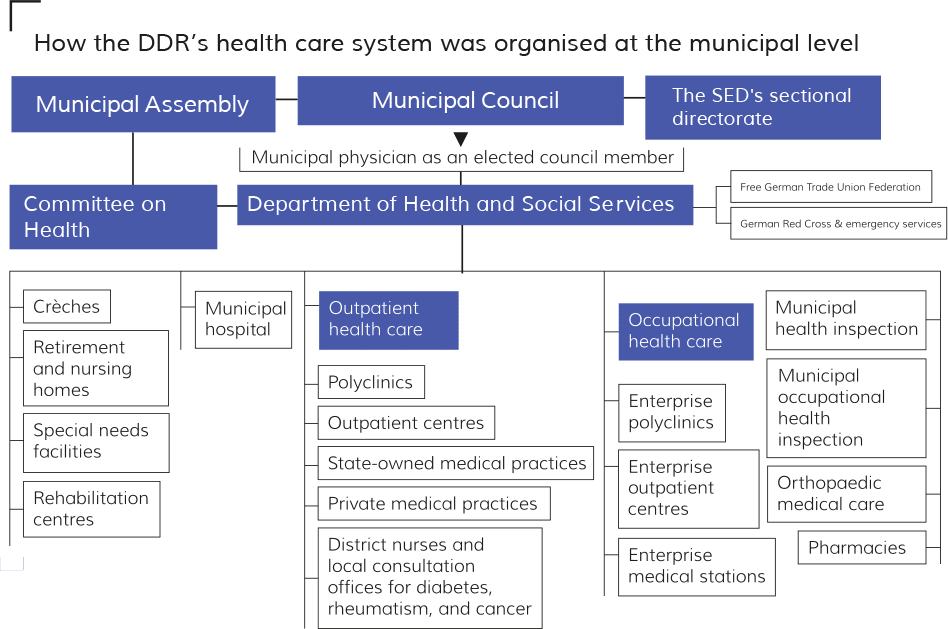

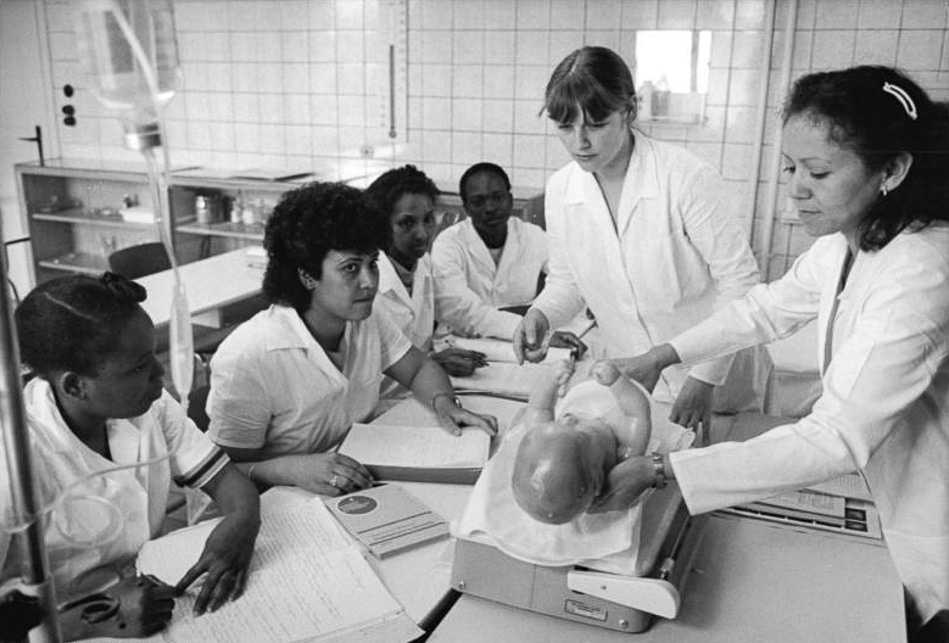

For me, after growing up in the United States, much of what I found was highly impressive, if not wondrous. The monthly social security tax did not disturb me, but I certainly appreciated the fact that my nine weeks in the hospital with hepatitis, with all of the examinations and treatment, plus two four-week rehabilitation cures—one in a wonderful estate formerly belonging to the Siemens millionaires, the other a year later in Karlsbad, Czechoslovakia—were not only free of any expenses, but I also continued to receive 90 percent of my salary. My wife’s three rheumatism cures, including one in the healthy mountains of Poland, were equally free and salaried. Dental care, new teeth, eyeglasses, hearing aids, and prescription drugs were obtained without opening my wallet. So were all costs connected with the delivery of my two sons (including rides to the hospital, one in an ambulance, the other, more hastily, in a taxi cab). My wife received a six-month maternity leave with full pay (plus six more months if she wanted them—unpaid, but with her job secured), plus a handsome financial subsidy paid out in five installments aimed at improving health: the first two when she showed up for a doctor’s prenatal checkup, the main installment when she had the baby, and two more afterward, when she got postnatal checkups for herself and the baby. Also, from then on, everything remained freeL nursery, kindergarten, school, apprenticeship or college, and even post-graduate studies. If she had had no plans for having a child, or already had all she desired, after 1972 abortions and contraception assistance were free. Working women and single fathers got one paid day off every month, the so-called Household Day. Such things are all just dreams in my home country.

ZD: What were the differences between East Germany and West Germany in terms of eliminating the influence of fascism?

VG: Three ghosts played leading roles in West Germany after 1945. One was that of old Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Much of the social network that impressed me so greatly in the GDR also existed in West Germany; way back in the 1880s, Bismarck introduced accident and disability insurance and old age pensions, basically to pacify the workers and undermine their militancy. Similarly, the main reason the eight-hour day was introduced in 1918 by the Weimar Republic was to undermine the revolutionary spirit that arose in Germany after its defeat in the First World War.

A second ghost, this time benefiting West German workers, was the rivalry with the GDR after 1945. For many reasons I mentioned earlier, they had higher living standards from the start. But in many ways, the GDR had more favorable working conditions, full job security for young and old, a general lack of pressures and stress in its workplaces, and far more equality for women—and this presented a threat for the wealthy and powerful in the West. Might some West German workers begin to look eastward and like some of what they saw, and some Eastern workers look westward, and better appreciate some good features where they were? Any such possibilities must be counteracted. This meant that Western unions, when negotiating with the bosses, had the GDR as an invisible ghost sitting on their side of the table, resulting in greater employer flexibility and improved chances for winning concessions, often without strike battles and their resulting (and troubling) militancy.

The third ghost, affecting not only working people, was the ghost of Hitlerian fascism. When the Federal Republic was founded in 1949, its leaders quickly discovered two crucial doors into the desirable club of “western democracies.” One was loud denunciation of Hitler’s misnamed National Socialism, praising democracy and setting up federal and state parliaments with elected delegates from a variety of parties, now very self-righteously anti-Hitler (but also very desirably anti-Communist and anti-USSR).

The other door was loud condemnation of Hitler’s major crime and major sin, the Holocaust against Jews. Proving this newly adopted disavowal required reparation payments to those Jewish survivors or their families living in the Western world—and befriending, supporting, and subsidizing Israel. Any departures from these positions endangered Germany’s acceptance and were to be publicly exposed and condemned.

But, away from politicians’ speeches and the quotable German media, under the loud, conspicuous surface, lesser known former Nazis retained or seized power and ruled the roost—nearly every roost! The great majority of school teachers, though sometimes dropped in the first year or so, were reinstated, along with school principals. Pro-Nazi professors, at first rather reclusive, were soon lecturing students again. Judges and prosecutors who had sent hungry slave-laborers, doubters, protectors of Jews and foreigners, and, above all, members of resistance groups to their guillotine deaths were back at the court bar, up to the top levels, even sentencing troublesome left-wing activists, some who had suffered in Nazi prisons and camps. Policy meetings of police chiefs were like old-pal reunions of Nazi cops and Gestapo officials. The media swarmed with tried-and-true Nazi journalists, often in top posts.

This also extended to government circles. My first real job in East Berlin was with an English journalist and his bulletin, correcting distortions about GDR life, but also exposing leading Nazis in the Federal Republic, sent to English-speakers, especially in Britain, including all Labour MPs. In one issue, we published a world map, with every country where the West German ambassador had been a Nazi Party member marked by a swastika. The map was swamped, with hardly any exceptions from Chile to New Zealand, from Washington to London and Pretoria. A few, with the most vicious pasts, had to be withdrawn. Our bulletin was hated or feared by many a so-called diplomat.

Old Nazis also felt at home In the Federal Cabinet. One became chancellor, another president. Ten of the twenty-one ministers in the cabinet of Ludwig Erhard (1963–66) had been in the Nazi Party, eleven had been Wehrmacht officers. The foreign minister had joined the Storm Troopers. Minister Theodor Oberländer, as a top officer, had joined the Ukrainian nationalist Stepan Bandera (today a hero in Ukraine) in killing thousands of Jews, Poles, and Russians in Lvov in 1941. Thirteen of twenty deputy ministers had good jobs in Hitler’s times, such as Ludger Westrick, who had headed Germany’s biggest aluminum company, which had made Nazi war planes. Karl Friedrick Vialon was in charge of registering the clothes and other possessions of 120,000 murdered Jews from the ghettos of Riga and Belarus.

A key figure was Dr. Hans Globke (1898–1973), who, in 1938, had led in placing a “J” in the passports of Jews to prevent them from fleeing Germany, then forcing Jewish men to take the middle name “Israel” and Jewish women “Sara,” making identification easier, first for repression, then for deportation to the death camps. Fifteen to twenty-five years later, from 1953 to 1963, as head of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer’s office in charge of government appointments, Globke was considered (West) Germany’s “second most important man.”

It was Globke who arranged for Nazi Lieutenant General Reinhard Gehlen, chief of Hitler’s military intelligence service on the eastern front and, after war’s end, a key expert in shaping the new CIA in Washington, to move to Munich in 1955 and create the similar Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), or Federal Intelligence Service, staffed with dozens of old SS and Gestapo killers.

Two other groups were especially disturbing. Regarding the Bundeswehr, the armed forces, Defense Minister Franz-Josef Strauss said: “There must be a continuity of tradition between the German soldiers of World War Two and the German soldiers of the future. The duties the future soldier will face will be the same as those faced by the older generation of soldiers.” In 1957, General Adolf Heusinger became the first head of the Bundeswehr. Back in 1923 he called Hitler “the man sent by God to lead the Germans.” During the war, he helped plan strategy for every one of Hitler’s campaigns, including the mass killings of villagers in Yugoslavia, Greece, Russia, and Ukraine. In 1961, he moved upward to become chairman of NATO’s Permanent Military Committee in Washington.

His successor as top officer in Germany was General Friedrich Foertsch, convicted in the Soviet Union for purposely destroying the ancient cities of Pskov, Pushkin, and Novgorod, then freed at the personal request of Chancellor Adenauer. He was succeeded in 1964 by General Heinrich Trettner, once captain of the Nazi aviation squad that destroyed the non-military town of Guernica in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War, as shown in the famous painting by Pablo Picasso. Then, after Trettner, they ran out of old Nazi generals.

Even more fearsome, perhaps, despite their polished appearance, have been the giant war criminal companies. They were described on July 10, 1945, in the report of a U.S. Senate Subcommittee headed by outspoken Senator Harley Kilgore of West Virginia:

Hitler and the Nazis were latecomers.… It was the cartels and monopoly powers—the leaders of the coal, iron and steel, chemicals and armament combines—who at first secretly and then openly supported Hitler in order to accelerate their ruthless plans for world conquest.… Your Subcommittee finds that the German economy was developed as a war economy, and that its vast industrial potential remains largely undamaged by the war…that the leading German industrialists are not only as responsible for war crimes as the German General Staff and the Nazi Party, but that they were among the earliest and most active supporters of the Nazis, whom they used to accelerate their plans for world conquest, and that these industrialists remain the principal custodians of Germany’s plans for renewed aggression.

The companies of these warmakers—Bayer, BASF, Krupp-Thyssen, Siemens, Rheinmetall, Heckler and Koch, Mercedes-Benz—famous for over a century, remain today as famous and powerful as ever.

How did this compare with the East German GDR? It was the exact reverse. In conformity with the Potsdam Agreement of the three main powers in July 1945, Nazi teachers were removed from the schoolrooms, Nazi judges and prosecutors were barred from the courtrooms, Nazi policemen lost their badges, GDR diplomats and political leaders were now people who had been forced by the Nazi government into exile; who fought the fascists in Spain, the Résistance, and antifascist armies; or who had survived Nazi camps and penitentiaries.

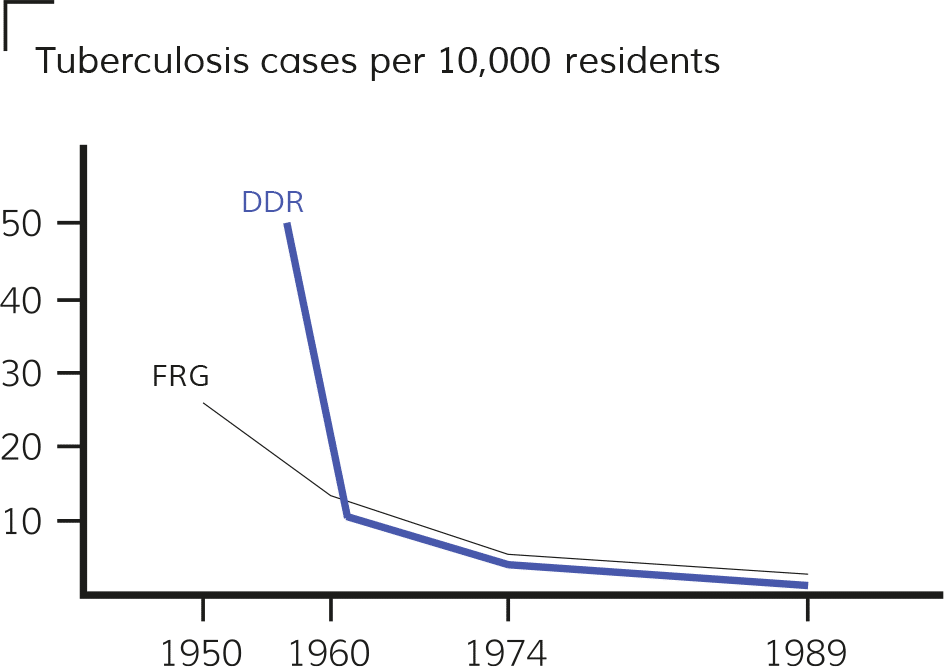

Few convinced Nazis slipped through—very few. Some were doctors who, regardless of their pasts, were desperately needed in the first hungry, cold years of typhus, diphtheria, and tuberculosis. There were also some military men. West Germany, in rebuilding their army within NATO, saw no problem in giving some four hundred former Wehrmacht generals shiny new uniform stars and renewed control. The GDR had almost no such resources to face the West German Bundeswehr, except a small number who fought in Spain, mostly in the ranks. This led it to turn to those few Wehrmacht officers who had turned against Hitler—not after 1945, when his defeat left hardly any alternative, but earlier, while the war was still on. This included some, often after being betrayed and abandoned by Hitler in the Stalingrad battle, who dared defy fellow captured officers and become convinced antifascists. Some of these, who rejected their former views and supported the GDR, were willing to help build up new armed forces, including nine generals (as opposed to about the four hundred former generals building up the Bundeswehr). Even these nine, though accepted as antifascists, were pensioned off as quickly as possible by 1957–58. Unlike the Bundeswehr, the only military traditions honored were those of popular rebels and antifascist heroes.

What about those cartels and monopoly powers that Senator Kilgore’s Subcommittee had warned about? On June 30, 1946, in a referendum in the GDR’s main industrial state of Saxony, 77.56 percent of voters approved the confiscation of those powers’ property, intact or war-damaged, because of their enormous war crimes, such as the exploitation of captive labor, at a horrific cost in misery and death. This property then became “publicly-owned enterprises,” with all earnings going either to employees as fairly paid wages and salaries or to social benefits for the people. None were set up for private profit. Legislatures in the other GDR states passed laws with the same content.

ZD: What caused the collapse of East Germany and the fall of the Berlin Wall? What problems existed in East Germany at that time, and why did many East Germans want to cross the Berlin Wall to live in West Germany?

VG: I think the basic reason for the collapse was simply that the other side was stronger and wealthier. But many factors involved are still debated among those of us who saw the GDR as a troubled yet brave attempt to create a decent, antifascist, and indeed, a socialist Germany.

It was an amazing achievement from the start that after May 1945, a small number of devoted leftists, mostly Communists, facing a demoralized, cynical, and mostly hostile population in this poor little rump of a country, despite losing most of its skilled (but pro-Nazi) engineering, management, and academic experts, and despite being denigrated and ostracized by much of the world, could lead in building up a state with high living standards and culture, almost totally free of poverty.

Certainly, a major reason why more of its citizenry did not appreciate this and try in every way to preserve it was rooted in that human failing: consumerism. “West-TV,” alongside cleverly honed disparagement of everything in the GDR, offered in soap operas and in commercials a constant display of handsomely packaged commodities, with the effect, if not the intention of winning over Easterners. Secure jobs? Free child care, medical care, and college? Dirt-cheap rents, vacations, books, records, and theater? These were increasingly taken for granted by each new generation, who grumbled instead at the long waits for a private telephone or a little Trabant car. Alas, it was very hard to get those early computers. There was not a chance at a Mercedes—or even a Harley-Davidson—or Marlboros, or even a test try of “weed.” No, not even bananas! Indeed, many called the events of 1989–90 the “banana revolution.”

Why couldn’t the GDR catch up? I have mentioned its basic geographic and historical disadvantages. There was also a simple lack of experience in a new form of economy, as opposed to the century-old, well-oiled model in the West, with its profit-motivated “carrot and stick” society. The carrot: those enduring U.S.-style hopes to “make a pile,” to move upward, to get richer—maybe just open up a new bar, maybe develop some surefire idea for a new app or cellphone novelty, or some new fashion. So many have scraped together all possible investment sources for some great new “better mousetrap” venture. Often enough it fails or goes bankrupt, with all the heartache for the entrepreneur and those he has hired. But a few succeed, go big, perhaps get bought by an older or larger firm. The market gets filled with ever new fashions and commodities, and many customers are happy. Such motivating carrots were extremely rare in the GDR, since no one could make millions in profits.

The stick was also lacking. No one feared going bankrupt or losing a job. Did that mean that people did not “knock themselves out” when at work, thus helping to explain the GDR’s lower productivity? As for having the workers themselves run the factories they were said to own, it was found easier to inspire a working force with enthusiasm shortly after a revolution—also a curious revolution from above, like that in the young GDR—than to maintain a high level of interest over years and generations when most people at the end of a work day are more interested in going home for supper, family, TV, or, on weekends, movies, watching soccer, enjoying their bungalows and gardens, rather than not sitting in smoky meetings to discuss improvements in the factory.

Instead of sticks, ideally there should be an emphasis on good organization, morale, and a feeling of “belongingness” between the worker and the workshop. Much was done to established closer working relationships, such pleasant breakfast rooms, the lunchroom with its trained cooks (and usually a dietician), the kindergarten for workers’ toddlers, often a library, or maybe a bookshop. There was also someone to allot vacations, instructors for the apprentices, perhaps a staff member to encourage women to move up the management ladder, and, of course, safety inspectors. Aside from the regular managers, there was at least one union organizer and one Party organizer. Many such offices also had secretaries. Large combines had whole “cultural palaces” with groups for making music, dancing, and hobbies like photography and filming—with paid instructors. There were also trainers for various sports teams, their number decided by the size of the plant.

The large number of such people, despite many of their efforts, may not have greatly lifted the graph lines on productivity charts, though they did have some success in creating a different work atmosphere than in the West, where the system’s “stick” meant exerting extreme pressure on fewer and fewer employees to assemble or concoct ever more tasty, brightly packaged, enticing but unnecessary (or even harmful) clothes, accessories, fast foods, over-sweetened drinks, opioids, poisonous pesticides, SUVs, and equipment to cheat testers and wear out after the guarantee period. The GDR also failed to achieve next-day delivery of Internet-ordered purchases In an ideal society, such pressures on warehouse workers with timers on their wrists, hustling bicycle delivery routers, truck drivers without rest stop time, all symbols of current development, will be forgotten. But as long as the rivalry between East and West Germany lasted, top speed and top productivity were factors that could not be ignored—and the West was always ahead!

In the 1980s, three big hindrances to its steady improvement faced the GDR. First, in view of the huge modern military build-up in West Germany, in collaboration with Rheinmetall, Raytheon, Lockheed, and so on, it was felt necessary to build up the GDR’s armed forces. While it could never match the West, it feared falling too far behind. That cost billions.

Second, while world trade became easier for the GDR after 1973–74, when it finally won diplomatic recognition by most countries, it had to keep up with latest developments in its exports so as to pay for imported raw materials and consumer goods. A main export product, top-quality machine tools, now also required modern electronics. But from where? The USSR needed such equipment itself. Companies like IBM and Sony were not allowed to sell their products to East Germany. The little GDR had to develop its own semiconductors, chips, and whatever else was needed. That cost billions more.

Third, in 1971, Erich Honecker was able to push out the aging Walter Ulbricht and win top control, evidently with the support of Brezhnev in Moscow, who disliked Ulbricht’s ideas on economic decentralization and attention to market principles (which perhaps approached the direction later taken by China and Vietnam). Honecker felt it wise to win the population by stressing higher wages, more support for mothers and the elderly, and, above all, better housing. A giant construction program was started up, promising to provide everyone with a modern home by 1990, and to do it without raising extremely low rent and grocery prices.

It was an admirable idea; before the end, almost two million new or renovated homes were made available. But this, too, cost billions, and Honecker refused to face the harsh impossibility of keeping such programs going while also helping weak industrial sectors, lessening debts, and balancing the budget. The resulting disproportions led to near-collapse in 1989. An ailing, politically isolated Honecker was removed on October 18 of that year—sadly, for it was too late.

There were other reasons for the downfall, within a few years. of all Warsaw Pact members, not least due to the CIA or its successors and its German sibling. GDR leaders were no match for them. Honecker, like Ulbricht before him, had controlled the SED party’s small Politburo circle that made all basic decisions. Many of its members had in their younger years been totally engaged—and toughened—in the fight against fascists: Ulbricht actively in exile; Honecker in a Nazi penitentiary for ten years; and others in the Spanish Civil War, the underground, or secretly within concentration camps. These men (almost all male) remained fully devoted to building and defending their lifetime goal, a socialist world benefitting all its people. But in a small state with its existence dangerously threatened, they saw a need for a strong central authority and pulling together without any differences and divisions that might enable hostile opponents to drive in a wedge and gain a footing. Actually, I think that every government that feels threatened tends to become more authoritarian, like the United States during its major wars.

However, when this leads large numbers of citizens to feel they have little share in decision-making, or are even excluded from doing so, then dangers may well increase, not lessen. With one of Honecker’s cronies exercising tight control over economic development while his mistakes and failure could not be criticized, disaster was hard to avoid. This held more than true for state security, the Stasi. With the media, also closely watched over by a Honecker pal, covering up the dangers descending on the GDR, boasting in a stiff, stilted language its self-righteous, self-congratulatory reports of economic successes (which were clearly exaggerated or false), a majority laughed at them with an unfriendly laugh, which for some, finally became anger.

The official GDR justification for such squelching of varied opinions, or of any discussion of alternatives, was that any criticism would immediately be misused by those across the border to weaken, split, and finally destroy the socialist experiment. There was truth enough to this: the fate of socialism in Chile or with Gorbachev’s Glasnost in the USSR are often cited as clear proofs. Even the slightest mistake or blunder, the smallest weakness or misdeed—and what country in the world is 100 percent free of corruption?—is seized upon and distorted by an often cleverly controlled “free press.” Any disagreements at lower levels or, better still, near the top, are magnified and used to encourage public disapproval. Such arguments against a freer press in the GDR received support from self-serving toadies who were quick to label genuine constructive criticism as “red meat for outside foes,” but really feared that their own inadequate or selfish work might be exposed. Which criticism was correct and justified, and which was primarily food for “damaging western propaganda”? The safest answer for some leaders was to take no chances.

A main result of this, of course, was that large sectors of the population looked regularly at the “news from the other side,” which, though exaggerated, distorted, and often false, was cleverly and interestingly presented, with its key messages framed attractively, like sliced salami, between vacuous descriptions of royal or celebrity love lives, detailed calamity and crime reports, excited sports reporting, or a veneer of broadminded discussion, minus left-wing views.

I still think that the main reasons for the GDR’s demise (aside from its vulnerability when its allies reversed) was the cleverness, flexibility, and, above all, the material strength of the victors in terms of commodities, as well as the lack of rapport between worn, often overaged leaders who considered themselves infallible and a population which could see and feel that they were not. They also explain why so few fought to save the GDR, despite decades of genuine success in winning a surprisingly large number away from fascist, cynical, or superficial ways of thinking to a general support of socialist ideas—an amazing achievement which faded more and more in the final two or three years.

ZD: After the fall of the Berlin Wall, what happened to the lives of the people in the former East Germany? Your books and articles talk about the negative effects of the fall of the Berlin Wall, such as deindustrialization, unemployment, loss of life security, and so on. How did this unfold?

VG: On November 4, 1989, a long, happy parade ended with a huge meeting at Alexanderplatz, East Berlin’s central square, where some twenty speakers called for a reform of the GDR—but not its abolition. Yet, the ruling Socialist Unity Party, the SED, had clearly lost control, and its opening of the Berlin Wall five days later marked the beginning of the end. On December 8–9 the party threw out its old leaders, chose new ones, formally rejected its claim to dominance, condemned “Stalinist methods” of the past, and soon added the words “Party of Socialist Democracy” to its title. But within the next three months, the die was cast, the Rubicon crossed. The election on March 18, 1990, sealed the GDR’s fate with the victory of an alliance of right-wing parties linked to the Christian Democrats of West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who had enthused attendees of well-organized rallies by promising that unification would soon bring “blossoming landscapes” with “no one worse off than before and many better off.” The Social Democrats, in second place, took basically a similar position, while the one and only pro-GDR party, in third place but with only 16 percent, was forced into a losing rearguard struggle.

Probably the concrete impulse for Kohl’s victory, more than blossoms, was his promise of that magic “West-Mark”—for a majority, that meant an end to the Eastern inferiority complex and a happy new life with all those fast cars, fashionable clothes, and fascinating travels—and, of course, the symbolic bananas and lots and lots of other goodies.

A chillier breeze, just eleven days after the decisive votes were counted, was the announcement by the West German government bank that one East-Mark would fetch only half a West-Mark, in other words a one-to-two ratio. After angry protests, exceptions were made; the desired one-to-one ratio would be granted to adults for 4,000 East-Marks, for 6,000 East-Marks to those aged 60 or older, and for 2000 East-Marks to each child under 14 years of age.

Anger at these very limited presents was largely swallowed when on Sunday, July 1, at the stroke of midnight, the very first West-Marks were given out. An eager crowd pushed so hard to be among the first that allegedly one man’s rib was broken. Soon, cars raced through the avenues, loudly hooping, with happy Easterners waving West German flags and handfuls of the magic new paper currency.

On Monday the shops opened, amazingly altered. Over the weekend, GDR products had been replaced by Western ones; from handsomely packaged sausage and fruit-flavored yogurt to armchairs, carpets, and refrigerators, all shiny and new, with those famous company logos Easterners had been eying for years on West-TV. In the weeks that followed, the streets were full of used, still useful but discarded GDR furniture, replaced in newly westernized bedrooms, living rooms, and bathrooms. Many a little Trabant was left deserted, while Opels, Fiats, and Volkswagens began to jam city streets. The bookshops were filled with travel guides, how-to books, gaudy paperbacks with sparsely-clad beauties languishing on the covers, and previously-banned political works by George Orwell, Aruther Koestler and especially Leon Trotsky. Totally disappeared were millions and millions of GDR books—not just those by Karl Marx or V. I. Lenin, but handsome art books, classics, and translations of American best-sellers were all literally dumped on garbage heaps or otherwise destroyed (including one of mine).

Before long, however, people began to realize that even crispy new West-Marks did not grow on trees, and must somehow also be earned. But where? On that same July 1, all 8,500 of the GDR’s publicly owned enterprises were taken over by a new West German government body called the Treuhand-Anstalt (“Trust agency”); not only factories, power plants, and mines, but big restaurants and hotels, most large-scale public housing, the DEFA Film Studios, the state pharmacy network, and even circuses, plus about 2.4 million hectares of agricultural land and forests. With over four million employees, the agency had become the world’s largest industrial enterprise. Its task was to tear itself apart, to privatize them all into the “free market”—that is, sell them off, split them up, or shut them down.

Many factories were indeed old-fashioned or in poor shape, with underinvestment due to the overriding prior need for modern steel, machine, and agricultural equipment projects. But some were recently built, reconstructed, and state-of-the-art. Their chances of survival, even if privatized, worsened by the month, since their major foreign customers, the Eastern Bloc countries, would now have to pay not with the former “transfer rubles,” but with hard-to-get Western valuta. Why still buy a former GDR product, whatever its quality, when, for a similar price, they could get a flashy, famous product from Japan, the United States, or West Germany? West German consumers, who had mail-ordered GDR products since they were good but cheap would now have to pay “normal prices.” Even the local market dried up, since East German customers rushed to get name-brand products they had yearned for, which were now in easy reach on supermarket shelves, with eastern products, if carried at all, only at stooping level.

If a factory was lucky, it was bought up by its former West German competitor, often some ruling giant, and used to make parts, taking advantage of the lower wages, longer hours, and intimidating pressures of threatening joblessness. However, many were bought up for a song, emptied of sellable machinery and then abandoned. A train trip through industrial areas showed empty brick factories marked by graffiti, broken windows, and widespread neglect. Clever hustlers made millions, while millions of employees lost their jobs. By 1994, billions in the GDR’s economic value had mysteriously been transformed into debt. This was blamed on GDR’s inefficiency.

Large numbers of administrative offices were also closed or sharply reduced, costing another two million jobs, with management taken over by second- or third-string “experts” from the West, who got special “bush bonuses” for the sacrifice entailed by working in the “backward East.” Some who commuted were called “Dimidos,” working Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays (Dienstag-Mittwoch-Donnerstag) as an Eastern manager, but spending lengthier weekends back home in western Hamburg or Essen.

I used to teach Improved English courses to scientists from the GDR Academy of Sciences. When this was shut down in 1991, a few of the best-known professors found positions in other countries or church hospitals. But most of my pupils, with or without doctors’ titles, lost their jobs and often their scientific profession. In the universities, almost the entire teaching staff in social sciences was thrown out: History, Law, Languages, Sociology, Philosophy. Natural science professors were judged by a committee of western rivals; if they had had any contact with the Stasi”, as most scientists did if they traveled to the west or needed western equipment, or had held even a minor function in a Socialist Unity Party group, they were ousted, even more allegedly than Jewish academicians ousted in the early years of Hitler.

Nearly all radio and TV journalists were fired, and all programs scrapped—except only a good night story for kids, the “Sandman.” Also dropped were countless journalists from the newspapers, now divided up among western publishers, all of them with sharp anti-GDR viewpoints. A friend of mine, a fine journalist, kept his job with an illustrated magazine, but as a subordinate to a new young Westerner with no knowledge of East German affairs, habits or wishes but with a higher salary, until this popular magazine went down the drain like most of its East German siblings.

Many towns had centered around one or two factories, offering jobs for generations to the employees or those who serviced them. When they shut down, so did the towns. Younger couples left, as well as many young women, searching for jobs in West Germany or abroad, while many lads, less able to manage without mother, hung around with no new orientation and little hope, until fascist types from the West—or emerging from Eastern woodwork—started organizing them. But it was largely the old folks who remained. In the cities, sacked men and women in their thirties tried to make ends meet by selling insurance policies or other such commodities. Sad-looking people in their fifties or sixties strolled idly through the streets and parks.

After the first welcoming euphoria, many “Wessies” tended to look down on their poorer Eastern “brothers and sisters.” They were overwhelmingly hated by the “Ossies,” the people of the Osten.

ZD: Many Eastern Europeans now miss their life under communism. This phenomenon also exists in Germany where it is called Ostalgie. How does this phenomenon occur?

VG: Ost means East in German. The word Ostalgie was invented by the media to describe nostalgic recollections and emotions of East Germans regarding their sunken ship, the GDR. It is most apparent in occasional “East markets” offering foods and other products once sold in every GDR grocery shop but then scorned, or at best banished, in now-privatized supermarkets to shelves too high or too low to be easily reached. But after a while people began to recall how good many of them were: the detergent Spee, mustard from Bautzen, Rotkäppchen (Little Red Ridinghood) champagne with its red cap, some favorite beers, sausage varieties, fruit jams, and, most famously, the delicious dill pickles from the Spreewald area south of Berlin. Though no longer produced by publicly owned enterprises, but those that are profit-based, these products revived the same good ingredients, recipes, names, and packaging. “East markets,” open often for just a few days, are always jammed.

What about attitudes on more basic aspects of that system, GDR socialism (never called “communism” officially, which was viewed as a future goal, achievable only with total abundance)? They are still varied, as they were back then, when some loved the GDR, its accomplishments and dreams for the future, some hated it and favored capitalism and wealth (for those who had it or those who hoped to have it if luck came their way) while the majority wavered and altered its views, often affected by personal successes or failures—a better home, a new car, a promotion, or a kid’s diploma—or a disappointment, often a delay or failure in those same items.

But the world has moved on; few East Germans (a recent poll estimated 10 percent) wish a return of the GDR, at best an unrealistic dream. Even faithful supporters recall the many weaknesses that furthered its downfall. Among them were the over-centralization of planning with too little reaction to market demands and far too little input into government from the entire population, with top-heavy leadership by a very few, whose main motivation no doubt was a better life for everyone but permitted privileges and perks for some leaders (though sparse compared with capitalist societies). We can add in the stuffiness and regulation in the media and the arts; the clumsy attempts in the schools to win over young people, too often achieving the opposite; and the pervasiveness of the Stasi. Ever since unification, a stress on such ills have been hammered into people’s heads, no longer only in channels from the “other side,” but in all channels, all media, all lecture halls, and nearly all classrooms. Even slight departures from this official denigration often required genuine personal courage.

(Much more at link.)

https://mronline.org/2024/04/23/from-ha ... t-germany/