Well, such was the case last week when Cascade Investment purchased 1.4 million shares of Republic Services, Inc. (RSG) for between $36.58 and $36.80.

Allow me to be perfectly honest…

Republic Services isn’t a particularly exciting business.

It’s not sitting on a treasure trove of patents.

It’s not on the verge of curing cancer.

And it’s definitely not unleashing a technology that’ll change the world.

So what’s the storyline here?

The storyline is the suitor. You see, Cascade Investment is actually a “holding company” upon which the richest man in the world likes to place his investment bets.

As it turns out, buying 1.4 million shares of Republic Services wasn’t this demigod’s only move. He also said “Sayonara” to another company, and dumped his entire stake in the firm.

Time to Mirror This Billionaire’s Move?

Bill Gates oversees an $81.7-billion fortune, which is almost $14 billion more than Mexico’s Carlos Slim, the world’s second-richest person.

Very quietly, with little fanfare, Gates has diversified well beyond his Microsoft (MSFT) fortune. In fact, these days, Microsoft only comprises one-fifth of Gates’ holdings.

A large remainder of his wealth is tied up in an investment holding company called Cascade Investment, which is headquartered in Kirkland, Washington, a stone’s throw from Microsoft’s Bellevue headquarters.

EXCLUSIVE CONTENT

Do NOT Deposit Another Dollar in Your Bank Account Until You Read THIS

A CIA insider has launched an urgent mission to expose the government’s secret money lockdown plan…

Once you see what could happen next time you go to an ATM, you’ll understand why he’s sending a FREE copy of his new book to any American who answers right here.

Last week, Gates bet big on the second-largest provider of non-hazardous solid waste management services in the United States, Republic Services. (The prior week, he liquidated his entire stake in British security firm, GS4 plc (GFS.L).)

Republic Services operates in 39 states – through its 199 transfer stations, 190 active solid waste landfills, 64 recycling centers, and 69 landfill gas and renewable energy projects.

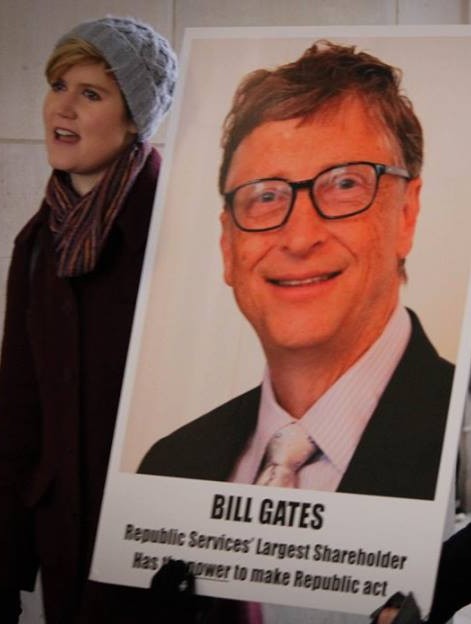

Gates’ $42-million purchase now brings his total holdings in Republic Services to over 91 million shares, making him far and away the company’s largest shareholder.

Other shareholders include fellow billionaires Mario Gabelli and D.E. Shaw.

Why is Gates so bullish?

Well, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, only 54% of total municipal solid waste ends up in landfills. So there’s plenty of room for the industry to grow.

Plus, Republic Services is an attractive backdoor play on the mushrooming recyclables market. As it stands, only $100 million of the company’s $2 billion in sales are derived from this lucrative segment.

When you consider the company’s P/E of 22, versus Waste Management’s (WM) 131, it’s difficult to make a bearish case.

Every segment of Republic Services’ business is showing growth, too.

Most importantly, though, for the first quarter of 2014, earnings grew to $0.37 per diluted share – compared to $0.34 per diluted share for the same period in 2013.

Share price always follows earnings (no exceptions).

So let’s follow Gates’ lead, and buy on any dips.

Onward and Upward,

Robert Williams

https://www.wallstreetdaily.com/2014/06 ... -services/

===========

Fighting the Toxic Nightmare Next Door

A radiation-riddled landfill in St. Louis, Trump’s EPA, and two moms who won’t let it go.

Infrastructure on the Bridgeton Landfill monitors and manages an underground fire. Republic built a plant on-site to process the increased amounts of toxic leachate produced by the high temperatures. PHOTOGRAPHER: JEN DAVIS FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

By Susan Berfield September 28, 2017, 5:00 AM EDT

It was practical considerations that led Dawn and Brian Chapman to Maryland Heights, a modest suburb of St. Louis bound by two interstate highways, several strip malls, an international airport, and the Missouri River. They found a three-bedroom, one-bathroom, 1,000-square-foot home near good public schools and parks, and a reasonable drive to her parents, for $146,000. By 2012, after seven years there, the Chapmans had three kids with special needs, and Dawn had given up teaching preschool to stay home with them.

That was when the stench overcame their neighborhood. It wasn’t the usual methane smell from Bridgeton Landfill, about 2 miles away, that sometimes wafted through. “It was like rotten dead bodies, and there was a kerosene, chemical odor, too,” says Dawn. “People were gagging.”

That fall the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that the odors were coming from a fire that had been burning 80 feet to 120 feet below ground at the landfill for almost two years and was likely to smolder for many more. The heat from the fire was accelerating the decomposition of trash, and the pumps and gas flares that normally remove toxic leachate and limit odors from dumps couldn’t keep up. Republic Services Inc., the company that owns the landfill, told the paper its staff was working to tame the “subsurface smoldering reaction”—an industry term of art for combustion that has no oxygen fueling it or flames rising from it.

When Chapman’s family and neighbors began experiencing headaches, nosebleeds, and breathing problems that winter, she contacted the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, which regulates the state’s landfills. She learned that Bridgeton Landfill was only one part of a 200-acre dumping ground that had been classified as a Superfund site because another part of it, an old landfill known as West Lake, contained radioactive waste from the earliest days of the Atomic Age. One of the two radiation-riddled areas was contiguous with the Bridgeton section. No one knew how the fire had started in the Bridgeton Landfill or when it would end, but it was slowly moving north, toward the contaminated area.

The Environmental Protection Agency, which called the whole sprawling dump the West Lake Landfill complex, had placed it on the National Priorities List in 1990 and announced a remedy in 2008. The plan was to cover the “radiological-impacted material” with several feet of topsoil, clay, and crushed rock and concrete. But the Missouri Coalition for the Environment argued to the agency that it was reckless to leave this particular element—thorium, a byproduct of uranium’s decay chain that becomes more radioactive over centuries—in an unlined landfill that sits in a developed area on a flood plain prone to tornadoes. An EPA review board also challenged the decision. Absent consensus, nothing was done. Officials were overseeing studies of other possible solutions when the landfill fire began.

Many people living near the site didn’t even know it was there, and most who did gave it scant attention. “We had no reason to look into the Superfund site before the smell, since it wasn’t a nuisance,” says Harvey Ferdman, a former volunteer policy adviser to Bridgeton’s state representative who now serves as an official, unpaid liaison between the community and the EPA. When he and Chapman first spoke in early 2013, she’d been poring through records dating to the 1970s collected by a lifelong antinuclear activist named Kay Drey. “Dawn told me about the illegally dumped nuclear waste, that there had been instances where it had gone off-site, which were documented, that when West Lake was unregulated it had received all kinds of toxic chemicals, including paint and jet fuel,” says Ferdman. “I told her, ‘No offense, but I’m going to be fact-based and objective. If 25 percent of what you’ve told me is true, we have a big problem.’ And unfortunately it all turned out to be true.”

In the spring of 2013, Chapman and a neighbor, Karen Nickel, formed Just Moms STL to advocate for the removal of the radioactive waste. Since then, the Moms, as they’re known, have held monthly community meetings, appeared at all of the EPA’s public sessions, kept watch on the Bridgeton Landfill fire, and become regulars at the state Capitol.

At the center of the swirling unease are the unknowable consequences of possible exposure to low-level radiation. With the initial recommendation to cap the waste, “the EPA has already established the fact that there’s a risk to human health if they don’t take action,” says Ed Smith, policy director of the Missouri Coalition for the Environment. His group wants some, if not all, of the waste removed from West Lake. But the EPA says that since no one is being exposed to the dangerous particles, there’s no current health risk. Republic argues that the agency’s recommendation to cover the waste is still the safest, quickest, and easiest remedy. At an estimated cost of $67 million, it’s also the least expensive; removing the contaminated soil could require nearly 10 times that amount.

Now, in a twist few would have anticipated, Scott Pruitt, the head of the EPA, wants West Lake to be a showcase of Trump-style environmentalism: dismissing climate change, deregulating industry, but taking action on toxic sites. Pruitt told a St. Louis radio host in April, “We’re going to get things done at West Lake. The days of talking are over.” A few months later, Pruitt said the agency was drawing up a list of the top 10 Superfund sites. West Lake is expected to be No. 1.

This would be great news in Bridgeton, but Trump’s proposed federal budget includes cuts to the Superfund program, and Pruitt has also promised to seek more cost-efficient remedies for the sites. “A million red lights went off when Pruitt talked about West Lake,” Chapman says. “There is no cost-effective solution for the site, only for Republic.”

As World War II raged, the U.S. sent spies on a top-secret mission to secure some of the world’s purest uranium from the Shinkolobwe mine in the Belgian Congo. It was shipped directly to Mallinckrodt Chemical Works in St. Louis, which developed techniques for purifying large quantities of the metal. Over the years the company chemically processed tens of thousands of tons of uranium, including the fissile material for the bomb the U.S. dropped on Hiroshima.

Mallinckrodt also produced about 2 million cubic yards of contaminated waste, some of which was transported hastily and carelessly in uncovered trucks to the St. Louis countryside in the late 1950s and ’60s, according to documents from the Atomic Energy Commission and its successor, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. From there, selected residue that still had some value was sold by the AEC; Cotter Corp., another uranium processor, eventually acquired about 100,000 tons.

After it stripped out copper, nickel, and cobalt from the waste, Cotter was supposed to dispose of what was left and decontaminate its storage facility in Hazelwood, northwest of St. Louis, by October 1973. As the deadline approached, things went awry. Cotter couldn’t figure out how to get rid of 8,700 tons of leached barium sulfate, which contained 7 tons of unprocessed uranium, and the commission didn’t have any suggestions. A contractor mixed the powdery white substance with 39,000 tons of dirt from the site—later also found to be contaminated with radiation— and, over three months, dumped it at the West Lake Landfill.

In the late 1970s the government began an assessment of the damage caused by the nuclear program, which ultimately led the Department of Energy to put Cotter’s Hazelwood site and Mallinckrodt’s St. Louis processing facilities, as well as two other storage sites, on its list of the country’s most radioactive areas. By 1990 estimates for the cost of cleaning up around St. Louis—which included the removal of tons of soil by the Army Corps of Engineers—had reached $1.5 billion.

When it came to West Lake, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission argued that oversight should fall to the EPA and its Superfund program, since the radioactive material had been dumped without governmental approval and mixed with other industrial waste. The program, which today includes some 1,300 sites, operates on the principle that polluters, if the EPA can find them, should pay to assess contamination and clean it up. At West Lake, the EPA named three so-called potentially responsible parties: the landfills’ owners (now Republic Services’ subsidiaries in Bridgeton); Cotter (whose liability passed on to Exelon Corp.); and the DOE. Identifying who should pay, though, is more a signal to queue up lawyers and consultants than the start of remediation.

“Follow the garbage trucks,” says Russ Knocke, Republic’s vice president for communications and public affairs, by way of directions from my hotel to the Bridgeton Landfill. The facility no longer accepts trash but does have a revenue-generating transfer station, which accounts for the truck traffic. At the entrance there’s a small, faded Republic Services sign, but nothing about a Superfund site. Knocke was press secretary for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security during Hurricane Katrina and joined Republic in mid-2013, as its handling of the fire was being questioned. He works from the company’s headquarters in Phoenix but has come to Bridgeton to meet me. He’s 43, wearing jeans and a button-down shirt; his hard hat is out, his presentation ready. With him are three of Republic’s experts on the landfill. “All the best in their fields, with years of experience,” he says.

When Republic took over the Bridgeton and West Lake landfills in mid-2008, following a $6 billion merger with Allied Waste, the transaction made Republic the second-biggest company in the industry by revenue. In the years since, Bill Gates’s money management firm, Cascade Investment Group Inc., has increased its stake to 32 percent. The Superfund cleanup was considered a footnote to the merger: Under the assumption they’d only have to follow the EPA’s requirement to cap the radioactive material, Republic expected to pay about $15 million, one-third of the estimated cost then. There had been at least one small fire at the landfill in 1992, but monitoring at Bridgeton was supposed to be routine. “Basically, we mow the grass,” says Knocke of the company’s other closed landfills. “A manager can oversee five of them at a time.”

At Bridgeton, Republic instead employs a full-time staff of 15, and twice as many consultants. The company has spent more than $200 million to monitor and contain the fire and estimates the total could reach $400 million. In 2014, Republic agreed to pay almost $6.9 million to settle a class action brought by residents who lived within a mile of the landfill over the odors emanating from it. The former Missouri attorney general also brought a suit against the company for allegedly violating state environmental regulations at the trash dump; a trial date has been set for next March.

The Bridgeton Landfill takes up about a quarter of the 200-acre Superfund site. It was created out of an old limestone pit and consists of the North and South Quarries, connected by a narrow area called the Neck. Just beyond the North Quarry is West Lake Landfill, where radioactive particles lurk below the surface, sometimes near it. We drive past a 6-foot chain-link fence topped with three strands of barbed wire. A yellow sign stamped with the symbol for radiation warns not to enter. The soil is covered in vegetation: green grass, dandelions, a few early summer wildflowers.

Bridgeton, in contrast, looks like a botched science experiment. Republic first reported evidence of a problem in its South Quarry—elevated temperatures and carbon monoxide levels—in late 2010. But the state’s Department of Natural Resources didn’t make the information public, and no one told the fire department until 2012. By then it was hard to hide: A 40-foot section of ground had collapsed as the heat consumed buried trash. “I wanted to give the company the benefit of the doubt,” Matt LaVanchy, the assistant fire chief, told me of his first meeting with Republic to assess the situation. “I brought up the fact that there’s a smoldering event in your landfill and a rad-waste dump that’s also on your property.” When he asked how they would keep the fire from the radioactive waste, “they said it was geologically impossible to reach the rad material because there is a natural barrier.” LaVanchy, though, says the trash spills over the quarry wall.

The fire’s origins are controversial. Republic’s experts say it began spontaneously, while two consultants hired by the state say the company may have inadvertently allowed oxygen to enter the ground through its methane wells or improperly maintained soil cover. Everyone agrees that extinguishing it isn’t possible.

“We’ve been the only adult in the room for a long time. It’s been this spin-up of noise and fear”

Republic tried to cool the hottest spots in 2013, but the heat began moving toward the radioactive material at a faster pace; in June of that year a representative of the Department of Natural Resources said the heat might reach the waste in 400 days. One landfill consultant’s worst-case scenario was a release of radioactive particles similar to a dirty bomb. In a report for the Missouri attorney general’s office, another expert brought up the possibility of superheated steam carrying radionuclides, which happened at the nuclear plant disaster in Fukushima, Japan. As fallout fears spread, the Moms put a countdown clock on their Facebook page and brought a child-size coffin and a petition calling for a state of emergency, signed by 13,000 people, to the governor’s office in Jefferson City. The expert who’d invoked Fukushima later said in a deposition that he hadn’t meant to alarm residents.

“We’ve been the only adult in the room for a long time,” Knocke says. “It’s been this spin-up of noise and fear and anxiety, and we generally feel like we’ve been the only ones that have been trying to say, ‘Guys, here’s the science.’ ”

“You might see the ground dry up a little bit; you might see cracks; you might see radon emitted into the air,” he says. “That’s the what-happens-if. Not St. Louis goes boom.” The Moms, he says, have shown “a complete disregard for science and distrust of institutions” and have scared the community.

Yet in the spring of 2014 the EPA’s Office of Research and Development concluded that, although a fire in the radioactive zone wouldn’t cause an explosion, it could present long-term risks, including the escape of radon gas into the air “at levels of concern.” A few months later the St. Louis County Office of Emergency Management devised a “catastrophic event” plan that instructed those far enough from West Lake to evacuate and those closest to shelter in place. (Republic takes issue with the radon data the EPA used in its calculations.)

Concern intensified in October 2015 when residents noticed a plume of smoke rising from West Lake, prompting panicked calls to LaVanchy. The smoke came from a brushfire about 390 feet from the nearest known location of contaminated soil. The fire department extinguished it within 20 minutes. The EPA later ordered Republic and the other responsible parties to put a noncombustible cover over areas where the radioactivity is close to the surface as a temporary measure.

Below ground, the spread of the heat was slowing and shifting direction away from the Neck. The most intense heat is now deep in the South Quarry, and Republic expects the reaction to wear itself out in seven or so years. “The threat of immediate concern about the fire is lower now,” LaVanchy says. “But I’ll feel a lot better when the temperatures everywhere start dropping and stay there. It’s not a stable situation. The fire is like a hostile animal.”

Erin Fanning, the chipper, 35-year-old division manager at Bridgeton Landfill, says that since the reaction began, Republic has installed 57 probes capable of recording temperatures to a depth of 150 feet, more than 200 gas extraction points, 28 cooling wells, and 51,000 feet of piping. Everything has to be kept working amid shifting ground. The cover—made from thin layers of the polymer resin ethylene vinyl alcohol, designed to keep in noxious fumes—requires constant maintenance. “A single fracture or tear could cause an odor,” Fanning says. A new waste treatment plant continuously processes the hundreds of thousands of gallons of hazardous leachate created every week by the trash as it decomposes rapidly from the heat.

Knocke casts Republic’s investments as evidence that it’s been a good neighbor. “We could have just walked away and said, ‘Catch me if you can.’ Now, without question, the state of the landfill today is as optimal as it’s ever been,” he says.

“When we hear this,” Chapman says, “Karen and I look at each other and we’re like, ‘You spent $200 million because this is a pretty goddamn big deal,’ ” and not something Republic could have run from. “We always say they bought a lemon,” Nickel says.

In the midst of Republic’s firefighting, the EPA made a discovery that further eroded the community’s trust in the company and the agency. Scientists found radioactive material 640 feet beyond where they thought it ended, in ground that had been considered part of the North Quarry of Bridgeton. Republic and the EPA said that even though they hadn’t known it was there they weren’t surprised to find it, and that since the waste wasn’t close to the surface it wasn’t a risk. “They’re confident they have found the extent of the contamination, and we don’t have the same confidence,” says Smith of the Missouri Coalition for the Environment, which wants the rest of the North Quarry tested. The EPA says that’s not necessary. But the agency has opened an investigation of the groundwater below West Lake after earlier tests detected radium.

This spring, Republic opposed a state bill that would have created a $12 million relocation fund for residents of Spanish Village and Terrisan Reste, a mobile home park, both of which are closer to the Superfund site than Nickel’s and Chapman’s houses. The company contended that it was unnecessary and would hurt the local economy. “Actually, Republic was lobbying against the precedent. It would be the first time a legislative body acknowledged there is a problem,” says Mark Matthiesen, the Republican state representative for the area, who shepherded the failed bill. “Every time we have some positive momentum, Republic starts working hard and putting more money to fight against it.”

Matthiesen has watched in frustration as Republic’s lobbyists have attempted to convince lawmakers that rural communities would be jeopardized if the EPA forced the company to remove the radioactive soil and an accident occurred during transportation. But the Army Corps of Engineers confirms that tons of such soil have already been moved through the state, accident-free, as the Corps and DOE clean up other contaminated sites in St. Louis County. Republic’s argument, Matthiesen says, “just isn’t right.”

Republic funds its own citizens’ group, the Coalition to Keep Us Safe, which seeks to assure Bridgeton residents that all is well and the real danger is in removal. The coalition has a Mom, too: Spokeswoman Molly Teichman, who lives several hours’ drive from Bridgeton, calls herself the Mommentator, and once tweeted, “Dear mombots of #westlakelandfill, your reality TV show is over. Go home and hangout with your kids—they miss you.”

The day after I tour the landfill, I visit Chapman and Nickel. They’re sitting at Nickel’s kitchen table in their usual chairs, wearing their usual summer clothes. Nickel is in a T-shirt and jeans; Chapman, a T-shirt and shorts. Nickel, who’s 54 and has three adult children and a teenage daughter, is sick with lupus, psoriatic arthritis, and fibromyalgia. She grew up next to Cold Water Creek, an area about 12 miles from Bridgeton that’s among those the Corps of Engineers is decontaminating. The U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry is now assessing public-health risks from any possible exposure.

Nickel worked as an accounting associate at a pharmacy company until it left town; now she cares for a few neighborhood kids after school. “I’m physically strong, but she’s the emotional anchor,” says Chapman, who’s 37. “I’m an analyzer and a processor,” says Nickel. “Dawn’s more of a jump off the bridge—”

“Jump off the bridge on fire,” Chapman interjects, before Nickel continues: “I’ve got to catch her by her feet and pull her back up and say, ‘Hold on. Let’s think about this.’ But it’s worked.”

They were in the midst of sorting through thousands of EPA documents that the Environmental Archives, a free digital library, had obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. In one email, an EPA representative remarked on a newspaper report that the activist Erin Brockovich was planning to meet with Chapman and Nickel: “SIX MORE MONTHS!!!!!.....AHHHHHHHHHH.” (In a statement, the EPA said the representative had been looking forward to retirement after a long career.) In another, employees discussed not using email.

“The EPA has spent more time handling the people in this community than worrying about what’s at that site and how it could harm the people of this community,” Nickel says. As we talk, she and Chapman receive a text from another activist, Robbin Dailey, who says she’d just missed the EPA officials walking around her Spanish Village neighborhood to placate residents, as they occasionally do. “I was going to lay into the EPA today,” Dailey says when I visit her and her husband later that afternoon. “They’re just mocking us.”

She and her husband, Michael, are retirees in their 60s, and he’s in poor health. They’ve lived up the hill from the Superfund site since 1999, in a home they bought for $110,000. For the past few years they’ve suspected it could be contaminated. About 18 months ago, attorneys at New York City-based Hausfeld, known for their fen-phen litigation, got in touch with them, proposing to investigate possible contamination in their subdivision. “I said, ‘Finally. We’ve got somebody that knows what the hell they’re talking about and agrees with us that we’re not crazy,’ ” Robbin says.

Scientists hired by the firm used a microanalytical method and said they discovered radioactive particles of Thorium-230 at concentrations 200 times higher than background levels. According to these experts, the thorium has the fingerprint of the uranium that was processed at Mallinckrodt. It was found in “archival dust” behind a loose floorboard in the kitchen where Robbin once hid the family’s valuables, as well as along the ledges of their basement windows and in a few spots in their backyard.

Last November, the Daileys, who chose not to accept the early class-action suit most residents signed up for because it would have limited other legal action, filed their own lawsuit against Republic, Cotter, and Mallinckrodt seeking compensation for property damage and the provision of remediation and medical monitoring. They want the companies to admit that radioactive material has already spread beyond West Lake—which the companies deny—and to pay them for their home, which they say they can’t, in good conscience, sell. (Knocke says that all neutral experts have deemed the community safe, and, in filings, all three companies deny the allegations.)

The family’s lawyers say there is evidence of Thorium-230 and other particles from West Lake in multiple houses in Spanish Village. But when scientists for the EPA tested two other homes near the Daileys using a more standard method, they didn’t find anything.

That didn’t necessarily surprise Marco Kaltofen, a civil engineer who devised the microanalytical approach and is principal investigator at consulting firm Boston Chemical Data. He used the same method to conduct a study, funded by Drey, the activist who provided Chapman and Ferdman with archival documents, that was peer-reviewed and published last year. He found radioactive lead, another decay product of the Mallinckrodt waste, in a roughly 75-square-mile area around West Lake and Cold Water Creek. The lead was at levels that were within EPA guidelines but exceeded the more stringent Department of Energy standards.

Tom Mahler, the EPA’s on-scene coordinator, emphasizes that the agency has been testing outside the Superfund site for the past five years and hasn’t found anything of concern. “Is it there?” he asks. “I cannot speak to whether something occurred if I don’t have data for it.”

“When you’re helpless, anything that gives you a little sense of power helps”

Living near West Lake means living with uncertainty. It’s difficult to measure exposure to a chronic, low-level presence of unstable material, and it’s hard, in an uncontrolled environment, to link it definitively with disease that can emerge years later. Lupus, for example, is an autoimmune disease that’s been associated with uranium radiation. Is this what caused Nickel’s illness? Right now, no one can say for sure. Science can help establish baselines for health risks, but those don’t map to every human body, and it takes only one cell mutation to cause cancer.

A 2014 Missouri health survey found higher-than-expected incidences of leukemia, colon, prostate, bladder, kidney, and breast cancer in communities near contaminated areas in north St. Louis County, especially Cold Water Creek, and a significantly higher-than-expected number of children with brain cancer in Maryland Heights. But the study didn’t assess exposure to radiation, noting that obesity, smoking, and diabetes can contribute to some of these cancers. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry concluded in 2015 that given the data from the EPA, other agencies, and the responsible parties, those living near the site aren’t facing any health risks from it.

While Faisal Khan, director of the St. Louis County Department of Public Health, accepts that finding, he also says that “the preponderance of anecdotal evidence supports Dawn’s conclusions of long-term, low-level exposure.” There’s no science to directly connect that to certain diseases, he adds, but no one should dismiss the community’s fears. “Their health concerns are valid,” he says, “and the level of anxiety related to the landfill and the entire toxic legacy is a huge disadvantage to their mental health.” Khan would like West Lake to be fully excavated.

“We expect the EPA to acknowledge that there has been some exposure at the low level,” says Chapman, “so that people can be proactive if they find a lump or feel sick.” When I ask Mary Peterson, head of the Superfund division that oversees West Lake, about this persistent worry, she replies: “I want people to have faith in government. Yet I know sometimes the answers we find in science, no matter how concrete, do not overcome people’s concerns.”

A few days after I leave Bridgeton, Chapman and Nickel travel to Washington with Smith and Matthiesen for the premiere of Atomic Homefront, a documentary about West Lake and Cold Water Creek that HBO will air early next year. Then they meet with Patrick Davis, a former Trump fundraiser who’s a political deputy at the EPA, and Albert Kelly, a former banker from Oklahoma who’s now in charge of streamlining the Superfund program, to press their case for getting at least some of the radioactive waste removed and helping to relocate those in Spanish Village and the mobile home park who want to leave. “They gave us their personal cell phone numbers,” Chapman says afterward. “That’s when I thought: We’re being played. When you’re helpless, anything that gives you a little sense of power helps. But now we see that’s BS. Every lobbyist has their numbers, too.”

Chapman and Nickel worry that Pruitt will side with Republic. “I suppose that’s a possibility,” Kelly says. “The opposite is a possibility as well. I’m sure somebody is going to be unhappy.”

Within months, they may know who. “After all these years, the decision will come down to one man,” Chapman says, sighing. “There’s no appeal.” Republic, Exelon, and the DOE, though, will have options if they don’t like the verdict. Superfund communities can’t legally challenge an EPA decision, but companies can. And if the EPA selects a remedy other than the cap, Knocke says, there would very likely be litigation before anyone lifted a shovel.

https://www.bloomberg.com/businessweek