The World in Economic Depression: A Marxist Analysis of Crisis

OCTOBER 10, 2023

Notebook no. 4 was researched and written by E. Ahmet Tonak (an economist at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research) and Sungur Savran (an instructor at Istanbul Okan University and editor of Devrimci Marksizm and Revolutionary Marxism).

The production team for this notebook, from editing to translation and design to our website upload, includes: Vijay Prashad, Celina della Croce, Mikaela Nhondo Erskog, Deby Veneziale, Pilar Troya Fernández, Maisa Bascuas, Emiliano López, Dafne Melo, Luiz Felipe Albuquerque, Cristiane Ganaka, Tings Chak, Ingrid Neves, Daniela Ruggeri, Amílcar Guerra and Ariana Hereñú.

INTRODUCTION

We are going through a period of profound uncertainty, morosity, and destitution. This is true even in imperialist countries, where the number of people in need of food banks is constantly increasing. In Britain, packs distributed by food banks more than doubled from 1.1 million parcels in 2015/16 to 2.5 million in 2020/21, with close to a million packs going to children in need.1The Trussell Trust, ‘End of Year Stats’, April 2021–March 2022,

https://www.trusselltrust.org/news-and- ... ear-stats/.

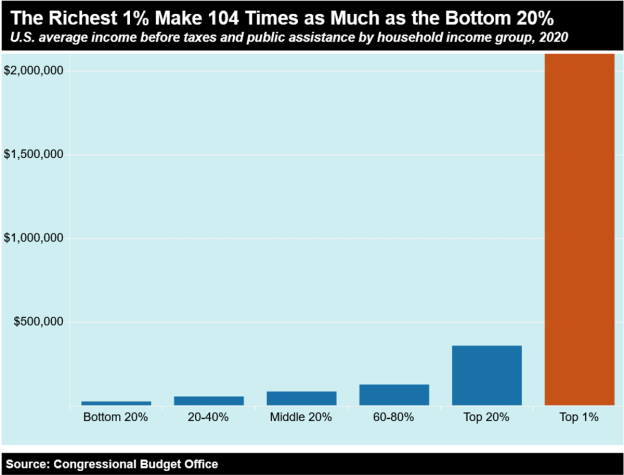

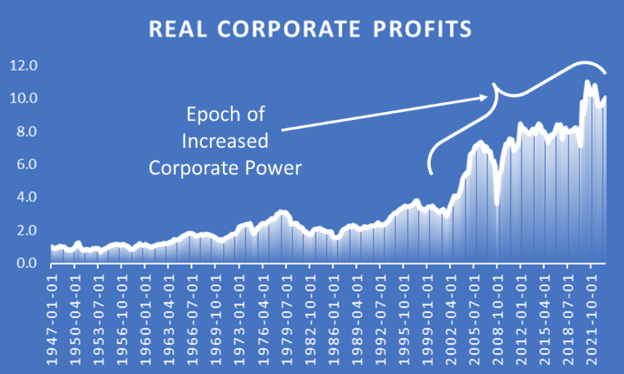

This does not mean, of course, that everyone is suffering. The net worth of billionaires around the world grew by more than $3.6 trillion in 2020, boosting their share of global household wealth to 3.5% even as the pandemic pushed approximately 100 million people into extreme poverty.2Tami Luhby, ‘As Millions Fell into Poverty during the Pandemic, Billionaires’ Wealth Soared’, CNN Business, 7 December 2021,

https://edition.cnn.com/2021/12/07/busi ... index.html.

The inequality that capitalism inevitably produces has created a world in which the richest 2,153 billionaires have more wealth than the poorest 4.6 billion people who make up 60% of the population on the planet.3Oxfam International, ‘World’s Billionaires Have More Wealth than 4.6 Billion People’, 20 January 2020,

https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases ... ion-people.

These twin trends are not peculiar to the impact of the pandemic: they have been going on for years, indeed for decades, woven together by the laws of capitalism in crisis.

In this notebook, we seek to shed light on the profound crisis of the world economy that has been unfolding for more than a decade. Explaining the crisis is not a meaningless exercise for the benefit of displaying the technical dexterity of professional economists. Rather, it is necessary to go beyond superficial manifestations to discover the essence of the entire process. In this way, we can shed light on the path forward for the working classes of all countries and the oppressed nations of the world in their struggles to turn back the tide of destitution and misery. In an effort to provide tangible and concrete results for the proletariat and the wretched of the earth, it is important to explain the inherent contradictions of capitalism that give rise to these crises. Incorrect explanations can only mislead the masses and harm their struggles.

It is common knowledge that the capitalist world economy experienced a severe financial convulsion in 2008, which has come to be known as the global financial crisis. The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, one of the big Wall Street investment banks, sent shock waves across the world, bringing the international financial system to a total collapse. Christine Lagarde, France’s finance minister at the time (later to take on the posts of managing director of the International Monetary Fund and then president of the European Central Bank), warned US Secretary of the Treasury Hank Paulson that they must not allow the sprawling insurance company American International Group (AIG) to fail immediately after Lehman Brothers.

The crisis was triggered by the bloated housing market, especially in the Global North (not only in the US, but also in Britain, Spain, Ireland, and other countries), a result of pushing mortgages even to consumers who would patently not be able to pay them back. Not only did the so-called sub-standard mortgage market, which had reached entirely unrealistic values, collapse, but, because these mortgages had been packaged into derivative products in financial markets in forms such as collateralised debt obligations and collateralised loan obligations, this collapse brought, in its wake, the collapse of other financial markets and left many banks and other types of financial institutions facing the precipice.

The name ‘global financial crisis’ was, at first, used exclusively to depict the profound crisis that the collapse of Lehman Brothers triggered in the world economy. However, it rapidly became a misnomer, as it became clear that the crisis was not peculiar to the sphere of finance but extended to the so-called real economy – in other words, the sphere of production. Steep, and to a certain extent unprecedented, decline was soon observed in such key variables as growth and investment as well as in a catastrophic rise in unemployment in many countries (at its worst, two European Union members, Spain and Greece, experienced youth unemployment that skyrocketed to more than 50% for years on end). Hence the ruling circles of the capitalist economy and governments began to use the neologism ‘the Great Recession’, coined by the Frenchman Dominique Strauss-Kahn (DSK, as he was known in financial and government circles), then the managing director of the IMF.

We refrain from using the term ‘great recession’ simply because, in our opinion, this was a smokescreen meant to hide the true nature of the crisis. A ‘great recession’ is something of an oxymoron. Recessions are conventionally defined as rather brief periods lasting longer than two quarters (or six months) that are fixed on a single economic variable, the rate of growth, when the latter enters the negative zone – in other words, when the economy shrinks. It is true that the world economy, as well as single national economies, did shrink immediately after the ‘global financial crisis’. However, many other factors were in play that are not encapsulated in the narrow technical concept of ‘recession’. ‘Great recession’ is an oxymoron simply because one cannot make the strictly narrow concept ‘recession’ do more work than the technical job for which it was invented. The appellation great recession was, in fact, invented by DSK to prevent state dignitaries, financial pundits, and the economics profession from using the ‘d-word’, i.e., depression.

The fact that the term ‘great recession’ was a smokescreen is also evident when one remembers what the alternative designation would have been. Alan Greenspan, who served as the chairman of the US Federal Reserve Bank for almost two decades, was among the most orthodox defenders of the rationality of markets and of capitalism. He made a lucky escape by retreating out of his role as the chairman of the US Federal Reserve Bank in 2006, thereby saving himself from being seen as the official directly responsible for the ‘Great Recession’. He was among many to say that this was a ‘once-in-a-century financial crisis’, a clear reference and comparison to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Thus, the ‘Great Recession’ concedes the ‘greatness’ of the crisis to conceal the fact that it was a depression.

Historically, capitalism has experienced different types of crises of varying intensity and duration. The most common among them generally occur roughly once in a decade and have conventionally been studied and referred to in professional literature as business cycles (the specialist writing on business cycles is outside the central core of mainstream economics for reasons we will be explaining in a moment). The culmination of a business cycle is, as a rule, a recession, a brief period during which the economy shrinks. This type of crisis is usually overcome through the adjustment of market forces, which has also been assisted to a certain extent by government policy since the post-war period in the second half of the twentieth century.

A depression is a different type of crisis in the history of capitalism. It lasts much longer, sometimes for a decade, sometimes for several decades. It cannot be managed and overcome through the conventional adjustment of market variables and requires radical convulsions not merely in the economic sphere, but also in the political, ideological, and even military domains. When a depression unfolds at the level of world capitalism, the convention, until now, has been to call it a great depression. The first such crisis – referred to as the ‘long depression’ at the time – took place at the end of the nineteenth century, approximately between 1873 and 1896. The second is the familiar Great Depression that began with the crash of Wall Street in 1929 and spread far and wide all throughout the 1930s, lasting, for many countries, especially those in Europe, until the end of the Second World War in 1945. In the opinion of many Marxist economists, including the authors of this notebook, the prolonged and profound crisis that we are experiencing today is also a great depression.

THE DIMENSIONS OF THE CURRENT CRISIS

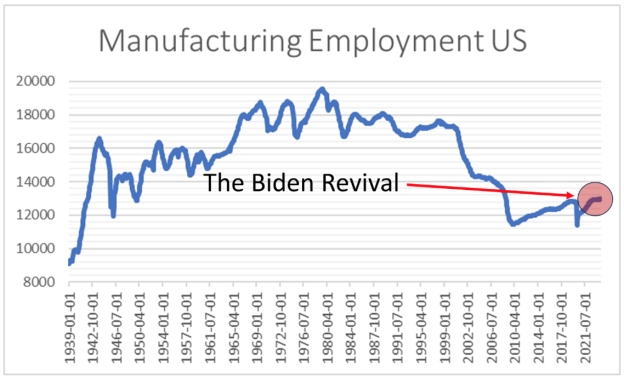

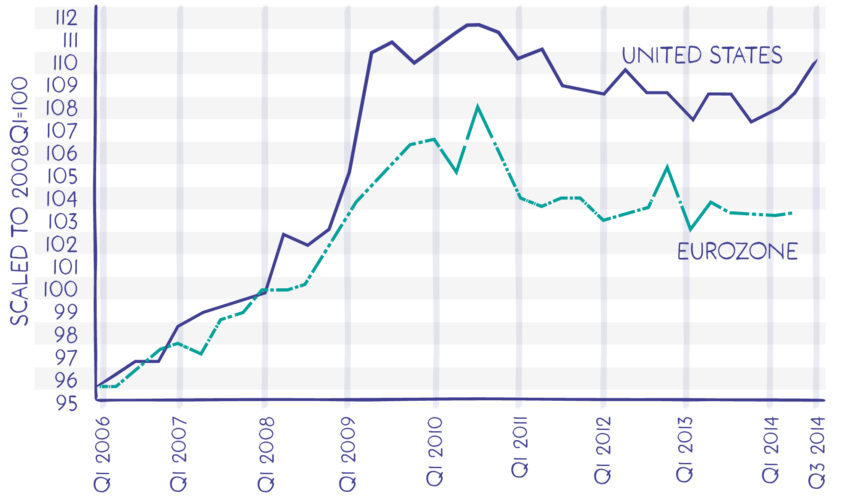

While the entire world has been experiencing economic malaise for a decade and a half, the trajectory and depth of the current crisis differ across countries and regions with diverse socioeconomic structures and varying positions in the world economy. The imperialist countries, for good reason as we shall see, were the origin of the crisis, and their populations suffered greatly throughout this entire period in terms of economic growth, investment, unemployment, and labour productivity. The United States displayed a trajectory of its own, recovering to a certain extent after 2013 and sustaining an edge over other imperialist countries, in particular Eurozone countries and Japan, until 2019, when it began to experience a slowdown. This would soon be coupled with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which began to spread with force in early 2020 as successive shutdowns took their toll on the country’s economic performance.

The so-called emerging countries (those that have been industrialising at a rapid pace over several decades or come from the background of a centrally planned economy), such as Argentina, Brazil, India, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, and Turkey, underwent a completely opposite trajectory from that of the United States. Having been shaken to some extent by the initial shock of the financial turbulence set on by the 2008 crisis, these countries soon recovered under the perverse mechanisms of capitalist finance to attain, at least in some instances, an economic performance beyond anything they had so far experienced. To take one example, the Turkish economy, after having shrunk during the first year of the crisis, recovered quickly to achieve, for the next two years, the highest growth rates the country had ever attained. The reason for the leap in economic performance in these countries did not necessarily have to do with their own policies. The most effective instrument that imperialist countries had to cope with the crisis was a policy of cheap and abundant money pursued by central banks, which made credit plentiful in these countries. However, since they drastically reduced interest rates for the same reason, finance instead flowed to countries where much more could be earned, namely the emerging countries. Thus, the bane of a world in crisis proved to be a boon for a certain group of countries whose economies were propelled by the inflow of all types of foreign liquidity. However, as the US economy began to recover in 2013, the Federal Reserve Bank changed its cheap money policy. This new policy orientation by the US Federal Reserve Bank initiated a period of hard times for emerging countries.

Though the less, and the least, developed countries faced differing scenarios, overall, they suffered seriously from the fall in international trade, which meant a reduced demand for their staple export products and an even higher decline in foreign direct investment. The price of primary commodities also took a beating. However, this had a differential impact on countries depending upon, for instance, whether the country was an importer or exporter of energy. In most of these countries, the overall impact was the accumulation of a mountain of foreign debt.

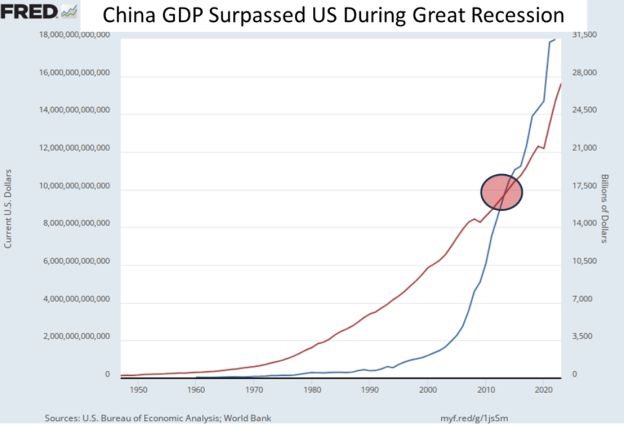

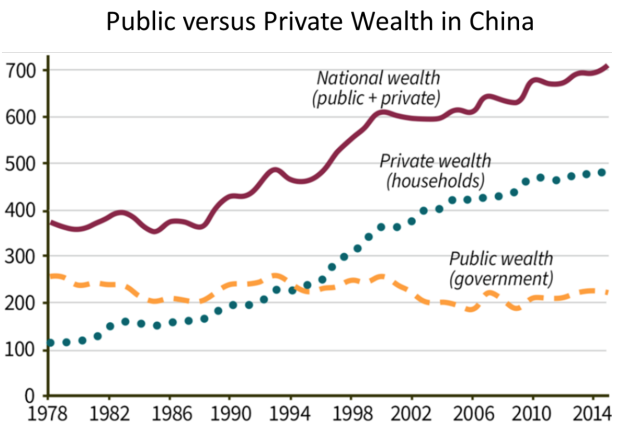

One country, however, was a category of its own: China. Although it considers itself to be a developing country, China has not suffered the same fate as the rest of the Global South, having maintained extremely high growth rates for decades based on its internal dynamics as well as its interaction with the rest of the world economy. Even since 2013, China has persisted as the single case that seems to demonstrate what many experts call the ‘decoupling’ of emerging countries from the imperialist ones.4For more on the concept of ‘decoupling’ or ‘delinking’, read Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research’s interview with Samir Amin, Globalisation and Its Alternative, notebook no. 1, 29 October 2018,

https://thetricontinental.org/globalisa ... ternative/.

Whatever the variety of experiences of different groups of countries, certain trends have inevitably had an impact on all groups in the long run.

Since 2008, there has been an overall slowing down of the economy both internationally and at the level of the richest imperialist capitalist economies (see figure 1).

Data from Michael Roberts, The Long Depression: Marxism and the Global Crisis of Capitalism (Chicago: Haymarket, 2016), 115.

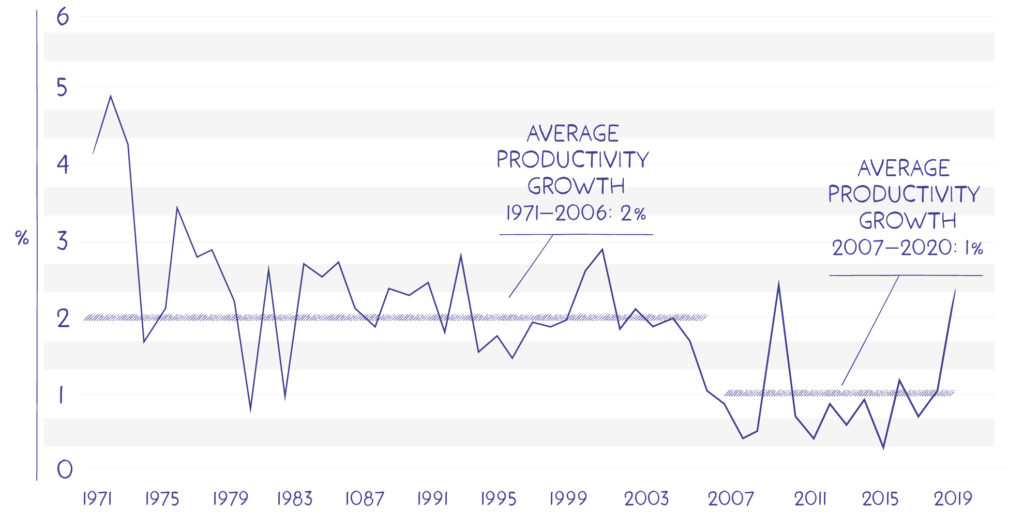

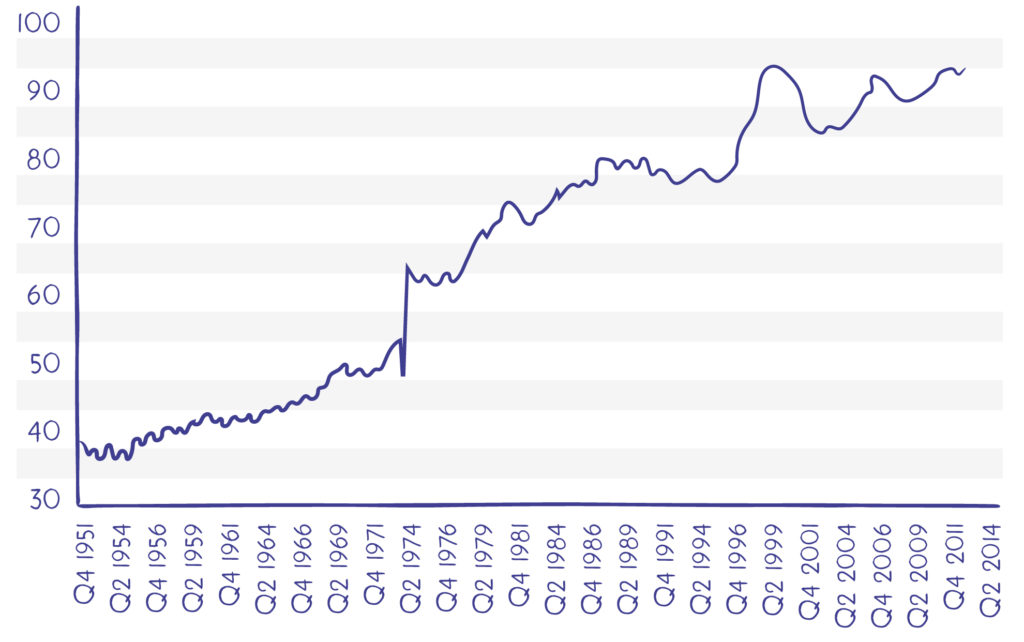

Investment, which had already been on the decline for a long time, took a nosedive in the period after 2008. Moreover, during the post-2007 period the average annual labour productivity growth rate in the G7 countries has hovered around 1%, a dismal performance compared to the 2% average rate from 1971–2006 (see figure 2).

Our calculations are based on data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation Development.

Given this reality, whatever dynamism existed derived from the policies of governments and central banks in imperialist countries that aimed to achieve a quick recovery of the world economy. This took two forms: monetary and fiscal.

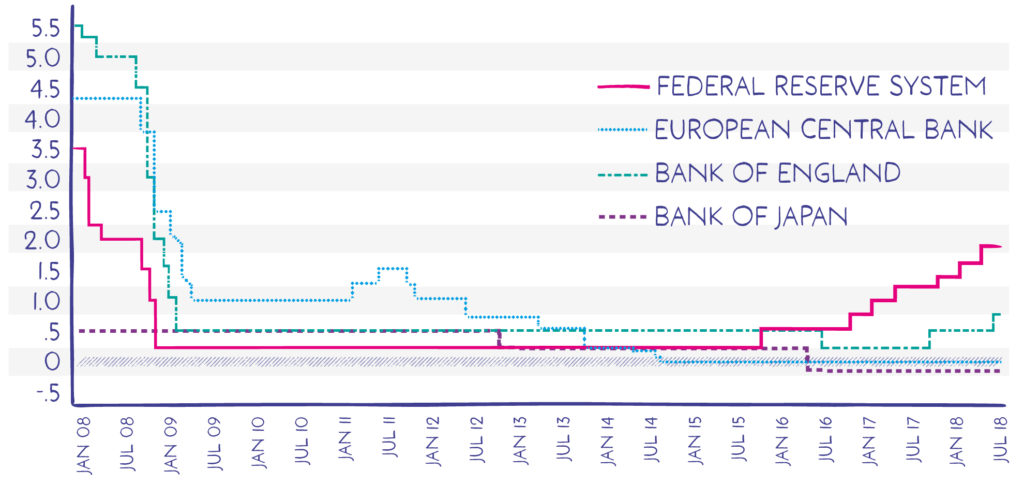

In the sphere of monetary policy, the central banks of imperialist countries followed in the footsteps of the US Federal Reserve Bank in aggressively pursuing a policy of cheap and abundant money. They did this in two different ways. The first was by reducing the reference interest rate all the way down to zero in many cases and even into the negative zone in others (see figure 3).

Data from Olga Kuznetsova, Sergey Merzlyakov, and Sergey Pekarski, ‘Confidence in Future Monetary Policy as a Way to Overcome the Liquidity Trap’, Russian Journal of Economics 5, no. 2 (July 2019): 117–135,

https://doi.org/doi:10.32609/j.ruje.5.38703.

The second was that the central banks pursued a policy dubbed quantitative easing, which involved the purchase of government bonds in the open market – i.e., going to the printing press. Quantitative easing was nothing but a hypocritical euphemism for printing money that was not backed by corresponding developments in the real economy. This manifested itself in skyrocketing growth rates in the central banks’ balance sheets.

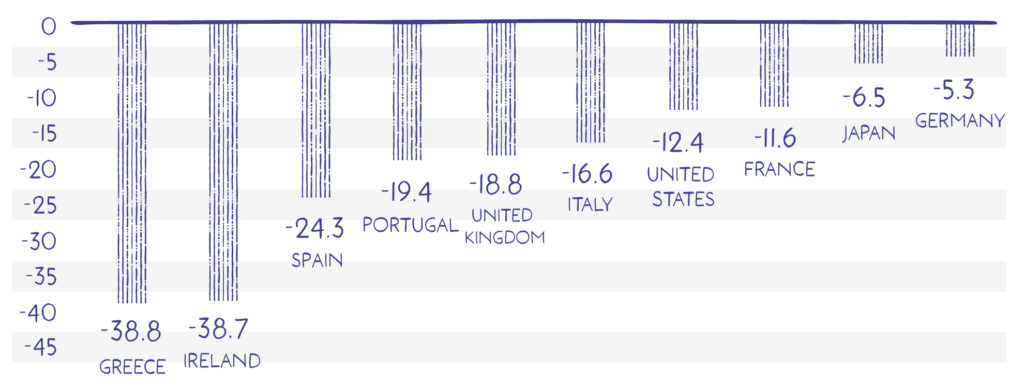

On the fiscal policy front, the United States and Eurozone poured vast amounts of money into government expenditure programmes that sought to recover the economy (see figure 4).

Data from Adam Tooze, Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World (New York: Viking, 2018), 355.

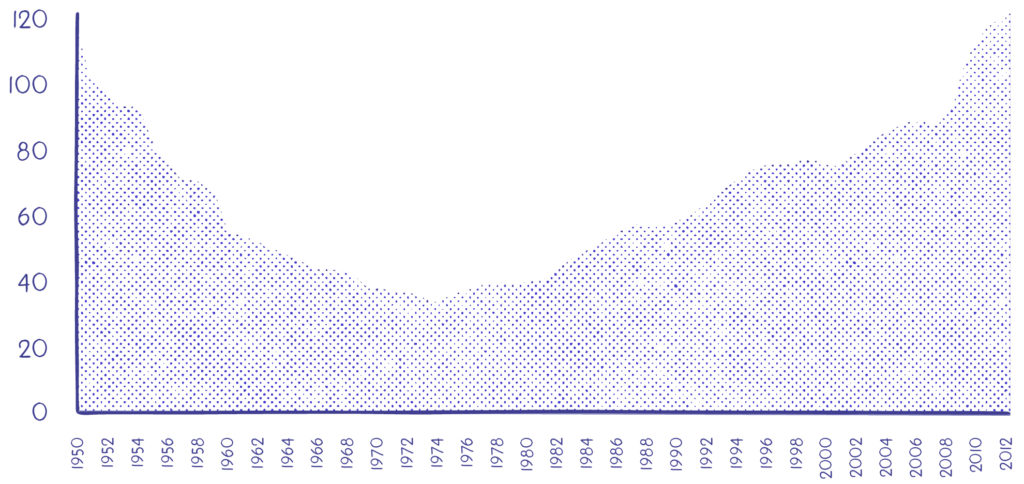

Naturally, deficit spending and a policy of cheap money create liabilities in the long run, as expressed in the snowballing debt of the major imperialist economies (see figure 5). Extraordinarily high levels of debt, which surpassed the 120% mark in 2012, signalled the highest public indebtedness in the entire history of the capitalist mode of production, breaking the record of wartime indebtment (see figure 5).5Murray E. G. Smith, Jonah Butovsky, and Josh J. Watterton, Twilight Capitalism: Karl Marx and the Decay of the Profit System (Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2021), 61.

By April 2023, US national debt had reached the staggering amount of US$ 31 trillion, which represented 124% of GDP.

Roberts, Long Depression, 68.

At around the same time, the 18 Eurozone countries had a debt-to-GDP ratio of 97.7%, although this varied wildly between the Mediterranean countries (Greece and Italy, for instance) and the countries of northern Europe.6Eurostat, ‘General Government Gross Debt – Annual Data’, accessed 22 April 2022,

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrows ... le?lang=en.

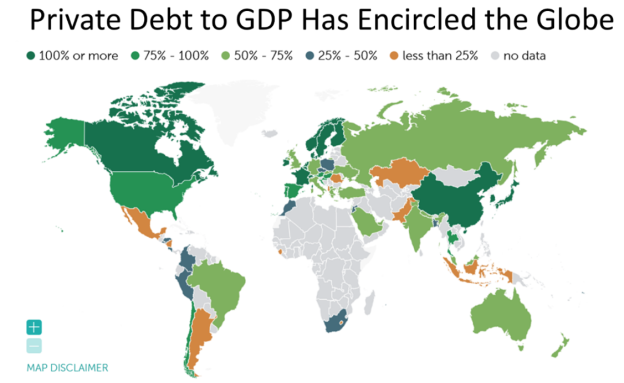

It is important to note that public debt is not the only burden facing the economies of imperialist countries: private corporate debt also rose immensely both before and after the global financial crisis (see figure 6).

Guglielmo Carchedi and Michael Roberts, eds., World in Crisis: A Global Analysis of Marx’s Law of Profitability (Chicago: Haymarket, 2018), 321.

As a result of this extreme policy of what is called pump-priming (i.e., stimulating an economy in recession), new bubbles are building up in stock exchanges and various markets such as housing, which have all grown at paces that are wildly incommensurate with the development of the real economy. Certain reliable experts on stock markets, such as the Nobel laureate Robert J. Shiller, have warned against being too sanguine about the ‘roaring 20s’ of the twenty-first century, since the previous roaring 20s of the twentieth century ended in the Black Tuesday of 1929, ushering in the Great Depression of the 1930s.7Robert J. Shiller, ‘Looking Back at the First Roaring Twenties’, The New York Times, 16 April 2021,

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/16/busi ... tocks.html.

Unforeseen events can also take a toll on economic cycles. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic has certainly impacted the economic cycle and made predicting future patterns more difficult. Another example of unpredictability is the war in Ukraine, which is also taking its toll on the world economy. In addition to the direct impact of the war, including convulsions in the markets of energy, metals, and foodstuffs, in which Russia and Ukraine are key players, the extraordinary level of sanctions imposed by Western countries on Russia and the boycotting of the Russian domestic market by Western companies have amplified the disruption of the world economy. It is no exaggeration to say that a decade and a half after the 2008 Lehman Brothers moment, the world economy is still in a sorry state.

EXPLAINING CRISES: MAINSTREAM ECONOMICS

Let us inquire into what mainstream economics has to say about crises under the capitalist mode of production. As soon as we turn to mainstream bourgeois economics for its characterisation of crises, we immediately come face to face with the utterly ideological and apologetic character of this discipline. An overwhelming part of mainstream economics is built on the assumption that economic crises are ruled out because of the fundamental laws governing the capitalist economy. There are, of course, dissenting voices, and we will come back to them. But it is noteworthy that, for two full centuries, since Say’s Law was advanced in the early nineteenth century, the bourgeois economics profession has overwhelmingly denied the possibility of systemic crises under capitalism. Though the rationale for this denial in technical terms has changed over time, the denial itself has remained consistent throughout. Let us then call this the denialist school.

THE DENIALIST SCHOOL

Say’s Law, the brainchild of the French economist Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832), is quite simple. It advances the idea that since all production under the capitalist division of labour is geared towards an exchange between the goods that each agent produces, it follows that all production creates a demand of equal magnitude of value for other goods, and hence all production creates its own outlet (Say called this the ‘law of outlets’). According to this law, total supply is thus necessarily equal to total demand, and so it is impossible for the economic cycle to be interrupted.

It is notable that David Ricardo (1772–1823), the greatest figure in the classical school of political economy alongside Adam Smith (1723–1790), adopted Say’s Law, which is, in fact, a vacuous tautology that does not stand up to even the slightest scrutiny. We shall come back to that shortly, but let it be said that, for half a century, Ricardo provided this supposed law its pedigree. Ricardo himself was not very optimistic about the historical prospects of capitalism. His theory of land rent shows that as capitalism progresses, land that is less and less fertile or more and more distant from metropolitan areas will have to be brought into cultivation. This process will necessarily raise the prices of foodstuffs, thus causing an inevitable fall in the rate of profit and, therefore, stagnation. However, this theory does not address capitalism’s periodic crises.

Neoclassical theory, which is currently the orthodoxy in mainstream economics, has faithfully subscribed to the denialist school of thought. From its rudimentary beginnings in the 1870s, when it was known as marginalist economics, until the general equilibrium theory developed in the wake of the Second World War and the rational expectations theory of the late twentieth century, the denial of economic crises was the hallmark of neoclassical economics.

Today, mainstream economists no longer present Say’s Law as the rationale to explain crises. What has taken its place is an argument alleging the smooth functioning of markets. This argument is based on the mechanism of market clearing prices (the assumption that demand and supply find an equilibrium price point). However, this assumption of the market clearing prices leaves no space for excess or insufficient demand. The recent concept of the efficient market hypothesis reproduces these earlier arguments with little elaboration. Stripped of technical jargon, all this implies is that capitalist markets are so rational and efficient in their functioning that they leave no space for gluts, deficits, or crises.

The reader may well be wondering how the economics profession came to terms with the fact that, throughout the entire history of capitalism, this denial has coexisted with the very real experience of capitalist crises. As we hinted at earlier, this was done through the development of a specialised literature on business cycles, which studies the seesaw-like alternation of growth and contraction within the capitalist economy at regular intervals. However, it must be emphasised that this quite sophisticated literature, which has recourse to a set of complicated technical tools, has never pierced through the thick ideological skin of the mainstream, the result of which would have been to question the efficient market hypothesis.

The economics profession’s alternative justification for the concrete occurrence of crises in the real world has either been to deny that there is a crisis worth naming (reducing the turbulence to a ‘correction’, a term borrowed from the professional jargon of stock exchange analysts), to attribute the crisis to an ‘external shock’ (war, revolution, an unexpected jump in commodity prices, extraordinary meteorological circumstances, etc.), or, most commonly, to mistakes in economic policy. As Karl Marx (1818–1883) wrote, ‘the apologists content themselves with denying the catastrophe itself and insisting, in the face of their regular and periodic recurrence, that if production were carried on according to the textbooks, crises would never occur’.8Karl Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, part 2 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1968), 500.

FOOTNOTE

There is an interesting anecdote that sheds light on this divorce between theory and reality in mainstream bourgeois economics. After the 2008 global financial crisis, Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom visited the illustrious London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). Like a naïve child asking the most untoward question in polite company, she asked the eminent economists gathered for the occasion – among them professors at the most prestigious universities, government advisers, and pundits for highly regarded organs of the financial press such as The Economist and Financial Times – the following question: ‘Why did no one see it coming?’.9Ann Pettifor, ‘I Blame the Queen for This Crisis’, The Guardian, 26 February 2009,

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfr ... capitalism.

There was no satisfactory reply. The duty of these eminent economists, up until the 15 September 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers, had been to defend the impeccably rational functioning of markets in the face of criticism from their hapless less orthodox colleagues, choosing not to reply to Marxist criticism so as not to lend it legitimacy.

KEYNES AND THE REALIST SCHOOL

The denialist school has never been the only current in mainstream economics. From the beginning, some economists held a more sceptical attitude towards Say’s Law, an outlook led by two very different figures: Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi (1773–1842), a social critic in Say’s own country, France, and Thomas Malthus (1766–1834), an extremely conservative parson in Britain and a friend of the liberal David Ricardo. Despite their uninterrupted correspondence on economic matters, Malthus was not able to convince Ricardo of the vacuity of Say’s Law. Ignoring exceptional figures such as William Stanley Jevons (1835–1882), a prominent representative of the marginalist school, and the towering figure of John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), a British public intellectual and economist who has to this day remained the major representative of what we will call the realist school, the Ricardo position on the question of crisis lingered all the way to the Great Depression years of the 1930s.

In his justifiably famous General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936), Keynes attacked Say’s Law head on and advanced the idea that the economy could in fact reach an overall equilibrium in a variety of different situations, such as when faced with underemployment or inflationary overheating on the one hand and a state of full employment on the other (which orthodox theory assumes to be the inevitable point of equilibrium).10John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (London: MacMillan, 1936).

This diversity of possible outcomes was, in his mind, what made his theory a ‘general theory’.

A crisis, according to the scheme developed by Keynes, is a state in which aggregate effective demand (i.e. demand at the societal level that is backed by money) is insufficient to create full employment. It is hence a state of underemployment and underutilised productive capacity. At first sight, this description suggests to the public that Keynes was talking about a lack of consumption power in society because of the poverty and destitution of the working masses. In fact, a broad school of thinking ranging from mainstream Keynesians all the way to a powerful tendency among Marxist economists draws the conclusion that a crisis can be overcome by raising wages and benefits. This is what is conventionally called underconsumptionism. We will come back to it shortly when discussing the diverse Marxist schools of thought. But, for the moment, let us remain within the boundaries of mainstream economics.

It is true that earlier critics of Say’s Law were underconsumptionists. Malthus even went so far as to claim that economic crises are caused by a structural lack of sufficient demand and that, to fill this gap, there needs to be a class of people who do not produce but only consume the revenue that accrues to them not for work but for other ‘services’ to society. However, to think that Keynes was a follower of Malthus would be a most unfortunate misunderstanding in the history of economic thought. Keynes was not an underconsumptionist. His entire corpus of thinking was centred around the decision process of the capitalist class, focused not on consumption but on investment. Keynes is a false friend that underconsumptionists cling to, and not always innocently, since Keynes can be a very powerful ally in pushing for certain policies. He himself was very clear that investment, not consumption, was the prime mover in the functioning of the capitalist economy.

Among mainstream economists, Keynes stands out for admitting that, because there are times when a drop in investment creates an underutilisation of the productive capacity and labour force of a country (or of the world economy as a whole), crises are part of the overall functioning of the economy. He then moves into the domain of the economic policies that governments can pursue in order to overcome such crises. Keynes is most famous for advocating not only for the type of monetary policy that many governments have pursued during the present-day crisis, but also, and very unconventionally for his day, a policy of government expenditure in the sphere of fiscal policy that seeks to stimulate economic activity.

Later, during the long post-war boom that lasted for roughly three decades (1945–1975), Keynesian fine-tuning policies accompanied a rise in state expenditure in advanced capitalism primarily in the spheres of education, health, housing, transportation, and other social services, also referred to as the social wage or the net social wage (i.e., the net taxes paid by the working population). This created the illusion that Keynesianism was some sort of social democracy promoted for the benefit of the working class. However, this is far from the truth: Keynes was a liberal bourgeois thinker who even advocated for a certain level of inflation in order to bring down real wages, which he alleged would make the recruitment of additional labour more attractive for capitalists, thereby reducing unemployment. Thus, the widespread thinking that Keynesianism is the perfect method to fight against crises in the name of labour is an illusion. It is certainly true that a rise in state expenditure under crisis conditions is a way forward so long as it is in the correct areas, such as education and health, for instance, rather than the military, but this fight need not be waged under the banner of Keynesianism.

The problem with Keynes’s explanation of crises is, in a nutshell, that his explanation for fluctuations in the volume of investment over time leaves much to be desired. Because his analysis of monetary theory is revolutionary in nature, the evolution of money and finance was a decisive factor for Keynes. Keynes brought into the picture different facets of capitalists’ calculations about the future, in particular their comparison between the expected returns from their capital investments (i.e., marginal rate of efficiency of capital) and the rate of interest, which is the cost of their capital outlay. Ultimately, he found that the determining factor for policy is in ‘expectations’ since both factors, ‘expected returns’ and ‘the rate of interest’, must be taken up in terms of their future development. This obviously begs the question of what determines expectations themselves, to which Keynes’ heroic reply was ‘animal spirits’.11Keynes, General Theory, 161.

Marx criticised Ricardo, the greatest bourgeois economist of the nineteenth century, for escaping into the field of agronomy in his theory of land rent because he had no overarching economic law of motion based on the particularities of the capitalist mode of production. Similarly, Keynes, the greatest bourgeois economist of the twentieth century, remained in the sphere of circulation and disregarded the relations of production under capitalism (and, in particular, its specific class structure). Without a theory of production, Keynes failed to determine the rate of profit and thus the pace of accumulation independently of the expected rate of interest. Instead, he took refuge in the field of psychology (‘animal spirits’) in order to explain the laws of motion of capitalism.

SCHUMPETER AND CREATIVE DESTRUCTION

There are always mavericks. Joseph Alois Schumpeter (1883–1950), an Austrian by birth, was decidedly a nonconformist among the economists of the twentieth century. For one thing, although he was a staunch defender of the capitalist system, he was deeply influenced by Marx’s thinking. For another, unlike most mainstream economists, even more so than Keynes, he was not a narrow-sighted specialist who shut himself within the technicalities of the economics profession. Schumpeter tried his hand in international relations (generating an original, if utterly failed, theory of imperialism), political philosophy (looking at capitalism, socialism, and democracy), sociology (investigating the role of the family in the formation of social classes), and other fields. He was the perfect example of the well-rounded intellectual of turn-of-the-century Vienna, where he lived as a young man.

Schumpeter’s theory of crisis (in the form of a theory of business cycles) has remained influential to this day, especially due to his original idea of ‘creative destruction’, and has become one of the most popular and widely discussed (if not sufficiently digested) explanations of the current crisis. To understand Schumpeter’s originality on crises, it is best to turn to the opening section of his book on business cycles:

Analysing business cycles means neither more nor less than analysing the economic process of the capitalist era. … Cycles are not, like tonsils, separable things that might be treated by themselves, but are, like the beat of the heart, of the essence of the organism that displays them.12Joseph A. Schumpeter, Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical, and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process (New York: McGraw Hill, 1939), v.

The title of his 1939 book from which this quote is drawn, Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical, and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process, makes it clear that studying business cycles is, in effect, studying the capitalist process itself. This sets Schumpeter apart from all the great mainstream economists – even from Keynes, who did not treat crises as integral to the essential workings of the capitalist system. For Schumpeter, on the other hand, the category ‘business cycle’, or ‘crisis’, is the kernel that makes for the beauty of this particular social formation, propelling the productive forces to continuously develop.

Innovation, for Schumpeter, whether technical, socioeconomic, educational, or otherwise, is the driving force of all human progress. Capitalism is distinguished from all previous formations because it makes innovation an indispensable element of its functioning, which it achieves through the very mechanism of crisis. Crises periodically cause the destruction of the previously accumulated productive forces, which then create both the need and possibility to fill this evacuated space with new productive forces that are of a superior quality and productivity because they embody the fruits of new scientific research, technological application, and innovation. This is the famous process of creative destruction, which makes capitalism an endlessly advancing force in history, always reaching out towards new horizons.

In many ways, Schumpeter’s vision of capitalism is quite similar to and was likely very much influenced by Marx, which is why he has been called a ‘bourgeois Marxist’.13George Catephores, ‘The Imperious Austrian: Schumpeter as Bourgeois Marxist’, New Left Review, no. 205 (May–June 1994): 3–30.

Both in The Communist Manifesto (1848), co-authored with Engels, and in volume one of Capital (1867), Marx had already emphatically and almost panegyrically stated that capitalism cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the means of production. This influenced Schumpeter’s thinking. What we do not know is whether Schumpeter was also aware that Marx envisioned crisis as the moment when capitalism, through the destruction of the established means of production, makes way for the new and more productive means of production, since Marx’s remarks on crisis are scattered across so many different writings, most of them not yet published when Schumpeter was writing Business Cycles in 1939.

According to Marx, the constant revolutionising of productive forces under capitalism prepares the ground for socialism. Schumpeter, however, saw the constant revolutionising of productive forces as an everlasting benefit that capitalism provides to humanity. His ideological defence of capitalism has two aspects. On the one hand, by making crisis a category that serves the progress of humanity, Schumpeter provided a justification for the devastation and misery caused by capitalism. On the other hand, his theory led to a one-sided understanding of crises: he limited the destructive force of capitalist crises to the means of production, whereas it is perfectly possible that these profound crises may well move society towards the destruction of the social relations of production. To put it differently, the spasms of crises may also prove to be the birth pangs of a new, classless society. The idea of creative destruction is thus formulated so as to preclude the more radical destruction that can be caused by crises – that of revolution, capable of creating not only new means of production, but a new society. Hence, Marx’s theory of crisis contains but also supersedes Schumpeter’s insight into the functioning of the capitalist mode of production.

EXPLAINING CRISES: MARX AND THE MARXISTS

The Marxist theory of the capitalist economy recognises the central place of crises in the historical motion of this mode of production, which is one of the most salient reasons why the Marxist analysis of capitalism is superior to mainstream economic theory. As we shall see, not only did Marx give due recognition to crises, which are a most common phenomenon of capitalist development, rather than denying their systemic nature, but he also went further and analysed them as the pivot on which the fate of the capitalist economy and society hinges.

MARX’S THEORY OF CRISIS: AN INTRODUCTION

To start with, Marx refused to grant even the slightest validity to Say’s Law. This was in stark contrast with the theories of Ricardo, post-Ricardian economists, the theoreticians of the ‘marginalist revolution’ of the 1870s (Stanley Jevons, Karl Menger, and, most importantly, Léon Walras), and the entire neoclassical school of economics that gradually formed in the footsteps of the marginalist school. Despite this, Keynes did not give Marx the credit he deserves, though he praised Malthus at length for his insight into how a possible lack of effective demand can lead to a crisis. Keynes’s bourgeois prejudices are likely the only reason that he underestimated Marx. In his General Theory (chapter 23, section VI), Keynes took up Silvio Gesell (1862–1930), an idiosyncratic figure in the history of monetary theory and the finance minister of the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919. It is in the context of a comparison with Gesell that Keynes put forth his only assessment of Marx, writing, in reference to Gesell’s main work, The Natural Economic Order (1916):

The purpose of the book as a whole may be described as the establishment of an anti-Marxian socialism, a reaction against laissez-faire built on theoretical foundations totally unlike those of Marx in being based on a repudiation instead of on an acceptance of the classical hypotheses, and on an unfettering of competition instead of its abolition. I believe that the future will learn more from the spirit of Gesell than from that of Marx.14Keynes, General Theory, 355.

FOOTNOTE

Has anyone heard of Gesell in the twenty-first century?

Marx attacked Say’s Law for disregarding the possibility that sellers of commodities can delay their purchase of other commodities. Say based his reasoning on the fact that all commodity producers engage in production activities with the purpose of selling the commodities that they have produced in order to purchase other commodities. Hence, whoever sells buys. In the aggregate, this means that demand is created by supply. Marx pointed out the simple mistake here: although it is true that supply creates the capacity to purchase goods and services, the act of purchase is a separate transaction from the act of sale, since the two are mediated through the conversion of the value in question from the commodity-form to the money-form and back. Sellers may very well decide to withhold the money they have thus acquired. If a sufficiently large number of sellers were to decide that it is to their benefit to keep their money and spend it sometime in the future (i.e., hoard their money), there would be a shortcoming in the demand for the goods produced, triggering the possibility of a crisis. In other words, Say reduced the unity between sale and purchase that is mediated by money into an unmediated or direct relationship between supply and demand.

As we mentioned earlier, Marx regarded crisis both as a problem for capital accumulation but also as a solution. What we mean by this is the following: all crises of a sizeable magnitude reveal the contradictions within the process of capital accumulation, which are concealed during times of heady profit-making. As soon as accumulation slows down, all kinds of shortcomings and inadequacies of varying severity come to the surface. Among these, of course, is the fact that the means of production are undergoing moral depreciation and cannot continue to serve the capitalists who use them as the basis for their competitive effort in the market, whether domestic and/or international. Here, Marx and Schumpeter were in agreement.

Another aspect where Marx and Schumpeter agreed is that the destructive aspect of crisis contains within it a solution to the crisis at hand. According to Marx, any major crisis requires a solution to two problems. The first is that measures must be taken to raise the general rate of profit. The second is that the means of production that are subject to moral depreciation, that are no longer competitive, and that lag behind new and more productive capacity must be eliminated in order to give way to a new set of machinery and equipment and new methods of production. The modality of elimination of old productive capacity takes the form of what Marx called devalorisation (Entwertung in the German original). To explain the term briefly, Marx used the term valorisation (Verwertung) to refer to the process whereby production adds new, additional value to the object of labour through the expenditure of living labour. Since valorisation refers to the process of augmenting value, devalorisation refers to a loss in value, which can even reach the loss of the entire value. Through this process, the capital embodied in a plant, machinery, or equipment loses or sheds its quality of value to become worthless and can thus no longer serve as productive equipment. This is Schumpeter’s analysis of the destructive process of crises. The elimination of old, obsolete, or insufficiently productive machinery and equipment as a result of crises is also of fundamental importance in Marx’s analysis.

Marx, and the Marxists who follow his analysis, make a fundamental distinction between the triggering factors that cause a disturbance in the economy, which may then set off a chain reaction that transforms a minor disturbance into a major crisis, and the crisis itself, which is always different from the triggering element. A perfect example of this is when a rise in the price of oil provoked a major crisis in 1973–1974, which led to the onset of a long, depressive period of slow accumulation. However, the real cause behind that crisis of accumulation was the fall in the rate of profit over an extended period of time due to the progressive replacement of living labour by machinery and automation. Another more recent example is the subprime mortgage crisis that began in the US in 2007 and spread to the rest of the world in 2008–2009. The subprime mortgage aspect of the crisis was simply the detonator of a devastating collapse in the financial system, which had expanded well beyond the productive base of the real global economy. We will return to this mechanism in more detail below. For now, let it be noted that the tendency of bourgeois economics to attribute the root cause of crises to their triggering factor has resulted in great confusion among the public about the nature of crises.

There are many aspects to this dialectic between the real processes that cause crises within capital accumulation and the outward manifestation of these crises. One such aspect is the question of overproduction. Whether Keynesian or Marxist, all theories of crisis that identify capital formation (or investment) as the key element in the coming about of major crises acknowledge that crises start in the form of a glut of unsold commodities. However, certain observers of this fact deduce from the existence of these masses of unsold goods that crises are, in their essence, crises of overproduction. Such confusion between the essential processes that lead to crises and the outward appearances of the source of a crisis may lead to serious misunderstanding about crises.

https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-n ... ic-crisis/

https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-n ... ic-crisis/

(Much more, this is just the half of it.)