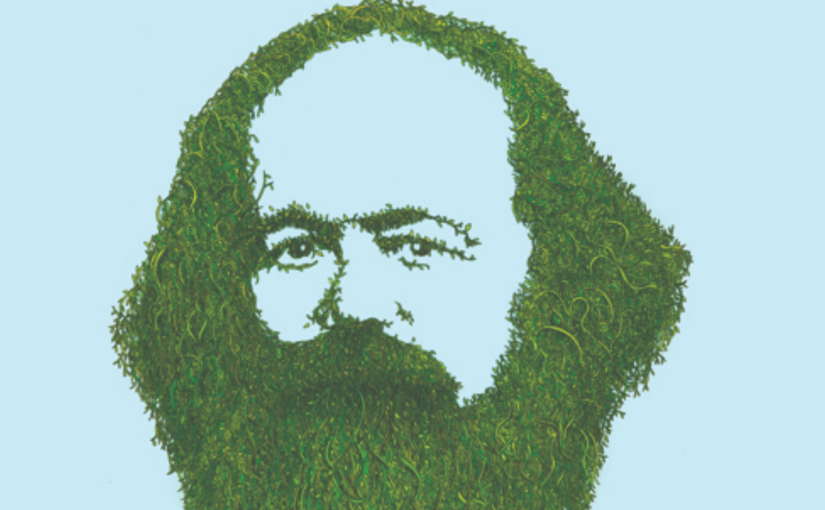

John Bellamy Foster on Ecological Marxism

John Bellamy Foster on Ecological Marxism

In this extensive interview, John Bellamy Foster, the editor of the long-established and prestigious US-based socialist journal Monthly Review and professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Oregon, discusses ecological Marxism, on which topic Bellamy Foster is an acknowledged global expert, with Jia Keqing, a research fellow at the Academy of Marxism of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Bellamy Foster begins by noting that the term ecological Marxism is widely used in China, but elsewhere the term ecosocialism is more widely used. Ecosocialism, he notes, has a complex history, with a number of its proponents in the 1980s and early 90s coming out of the Marxist and New Left traditions but being highly critical of Karl Marx and the classical Marxist tradition as a whole. “This also involved, in some cases, attempts to wed Marx with other figures, such as Thomas Malthus (falsely viewed as an environmental figure) or Karl Polanyi, who provided a more social-democratic political economy… Much of this was coloured by reactions at the time to the demise of the Soviet Union and attempts to distance ecosocialism from core Marxist traditions.”

However, from the late 1990s, such views began to be challenged by other ecosocialists rooted primarily in the unearthing of Marx’s own ecological critique. Marx, Bellamy Foster notes, “was strongly critical of the Cartesian mechanistic separation of human beings and animals and defended Darwinian evolution, emphasising the human coevolutionary relation to the natural world. He also emphasised the close affinity in terms of intelligence of nonhuman animal species and human beings, and he criticised the brutality toward nonhuman animals that arose within capitalist production… He also indicated that we relate to nature not simply through our production but also sensuously, and through our conceptions of beauty, that is, aesthetically… One of the most brilliant insights of Xi Jinping, in line with both traditional Chinese civilisation and Marxism, was to recognise that the concept of ecological civilisation was not quite enough, and that it needed to be supplemented by a notion of ‘beautiful China’. That is, our aesthetic relation to nature, and thus the intrinsic value of nature, was seen as so important that it needed to be emphasised separately.”

Discussing the relationship between ecological issues and the class struggle, Bellamy Foster traces things back to Friedrich Engels’s 1845 work, The Condition of the Working Class in England: “Engels did not start his analysis with the exploitation of factory workers and conditions in the workplace, though that occupies part of the book, but rather with the capitalist city, housing conditions, air and water pollution, the spread of disease and illnesses of all kinds, and the much higher mortality rate of the working class. In this sense, his work was ecological as much or more than it was economic.

“The struggles of the working class in the early nineteenth century were a product of their whole living conditions, not just factory conditions, even if it was their ability to stop production that was the basis of their class power… For Marx and Engels, working-class struggles were not restricted to strikes and battles by workers within their work sites but were also evident in the entire realm of working-class material existence. Historical materialism has too often been reduced to what we might call historical economism, leaving out wider realms of life.”

Bellamy Foster also incorporates the contradiction between the Global North and the Global South, as well as the complex relationship between working people in the Global North and the Global South, into his analysis, stating:

“If there is a shortage of food or water available to the population in the Global South today, is this due primarily to economic or ecological factors? The fact is that such problems are more and more intertwined given the structural crisis of capital and combined economic and ecological crisis and catastrophe…

“The economic proletariat has often been constrained by the logic of trade unions and the struggle for wages and benefits. The environmental proletariat, which is simply a way of referring to the proletariat in terms of the full complexity of its material existence, is concerned with work relations but also the full range of material life conditions. Such a unified standpoint is necessarily more revolutionary and more capable of grappling with the problems of the age…

“In terms of the question of the more revolutionary character of workers in the Global South, there cannot be the slightest doubt. It is the workers in the periphery of the capitalist system who are faced with the sharp edge of imperialism… Not all of these revolutions have succeeded, of course… Nevertheless, it is the proletariat/peasantry in the Global South that has continually led the way, and where one consequently sees the most radical environmental-proletarian struggles today.”

Bellamy Foster is clear that the historic responsibility for the looming threat of climate catastrophe rests with the imperialist countries and not with China or other countries of the Global South and draws on the work of Jason Hickel, who “demonstrated in an important study in Lancet Planetary Health in September 2020, [that] if we subtract the actual emissions of countries from their fair share, we can then determine which countries have, in their historical emissions, generated excess or surplus emissions. What Hickel was able to determine based on 2014 data was that 40 percent of all excess carbon dioxide emissions in the world added to the atmosphere were attributable to the United States, and 92 percent to the rich nations of the Global North. Meanwhile, China and India both had zero excess emissions. The excess emissions of the countries of the Global North represent an enormous ecological debt in the form of a climate debt to the Global South.”

Jia and Bellamy Foster discuss the ideas advanced by James O’Connor, founding editor of Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, regarding capitalist and socialist approaches to development and the ecological crisis. Bellamy Foster notes that: “Socialism arises out of capitalism and thus is inherently infected by many of its contradictions. The world-economy as a whole is capitalist, which means that socialist countries have to navigate their way through all sorts of external contradictions imposed on them, not least of all imperialist pressures. Nevertheless, what differs between countries who are socialist (or postrevolutionary) and capitalist are the social relations of production, which open up all sorts of new opportunities. China, for example, though beset with ecological problems, has been able to develop modes of ecological management and planning that would be unthinkable in the Global North/West.”

Asked what China should emphasise to tackle the ecological crisis and build an ecological civilisation, he responds: “China’s approach to building an ecological civilisation is radically different from anything that exists in the West/Global North. Xi has made it clear that the goal is to alter the whole ‘developmental model and way of life’… This is achieving startling results.”

Tackling the question of the share of coal-fired plants in China’s energy consumption, which has so far dropped from 70% to around 56%, he continues:

“A big factor in China’s continuing reliance on coal has to do with energy security, not simply economics. Coal is the only fossil fuel that China has in abundance. With the United States launching a New Cold War on China during the Donald Trump administration, which has been carried forward and intensified under the Joe Biden administration, energy security has become a bigger issue for China. As Xi put it in a speech in October 2021, China ‘must hold the energy food bowl in its own hands.’ In this respect, Beijing is very conscious of the whole history of imperialism and how Western powers had imposed sanctions on it during the century of Western ‘gunboat’ interventions enforcing unequal treaties, something that only ended with the Chinese Revolution.”

Bellamy Foster does not accept the view that China’s emphasis on ecological civilisation has little to do with ecological Marxism, but is mainly rooted in traditional Chinese culture, “Yet, I also argued that the notion of ecological civilisation was developed in China as part of an ecological Marxism with Chinese characteristics, drawing on China’s own vernacular revolutionary tradition and thus on traditional Chinese culture… My way of thinking about this was very much influenced by the work of the great Marxist scientist and leading Western Sinologist Joseph Needham, the principal author of the massive multivolume Science and Civilisation in China.”

Finally, Bellamy Foster firmly locates his arguments in the context of the New Cold War primarily initiated by the United States against China:

“The United States is currently threatening the People’s Republic of China over Taiwan, which is internationally recognised—by the United States as well—as part of China, but with a different system, in accord with the One China Principle… In the context of declining US economic hegemony, Washington is insisting on a unipolar world, promoting military blocs aimed at China and Russia, and rejecting the actual multipolar development of the world at large, through the development of the BRICS… The US dollar’s role as the international reserve currency is being weaponised to sanction both Russia and China, along with all other nations that have challenged US dominance… The world is therefore on the edge of a Third World War, threatening the very existence of humankind. China’s response has been to launch in 2022 its Global Security Initiative, which constitutes the most comprehensive set of commitments for overall world security, including the security interests of all nations, that has ever been introduced.”

This interview, which is well worth reading in full, was first published in English in the September 2023 edition of Monthly Review. Conducted in English, the interview was also translated into Chinese and published in World Socialism Studies (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) in April 2023.

Jia Keqing: John Bellamy Foster, thank you for taking time for this interview. You are a leading theorist of contemporary ecological Marxism. In recent years, you have published a large number of works on Marxism, especially ecological Marxism. Could you give us an overview of the current state of ecological Marxism research worldwide? For example, what are the representative scholars and representative journals?

John Bellamy Foster: In China, the term ecological Marxism is widely used, but in most discussions outside of Asia the term ecosocialism is more common. I use both terms, along with Marxian ecology. At present ecosocialism is how the actual on-the-ground movement is referred to in the West. Still, the term ecological Marxism is useful at times since not all ecosocialist currents are clearly Marxist. Indeed, some self-styled ecosocialists adopt a more social-democratic approach. Ecosocialism thus has a complex history.

In the 1980s and early ’90s, many of the most prominent ecosocialists, figures like Ted Benton, André Gorz, James O’Connor, and Joel Kovel, came out of the Marxist and New Left traditions but were highly critical of Karl Marx and the classical Marxist tradition as a whole for being what was termed Promethean (standing for an extreme industrialist and extreme productivist position) and for being anti-ecological. The main thrust was thus an eclectic combination of traditional Marxist positions on labor and class with a Green theory that was primarily ethical in nature. This also involved, in some cases, attempts to wed Marx with other figures, such as Thomas Malthus (falsely viewed as an environmental figure) or Karl Polanyi, who provided a more social-democratic political economy, sometimes characterized as more environmental than Marx’s analysis. For Benton, Marx had failed (in contrast to Malthus) to recognize environmental limits. For O’Connor and Joan Martínez-Alier, Marx had rejected ecological economics as presented by the Ukrainian Marxist Sergei Podolinsky—though later research proved this to be incorrect. In the case of Kovel, Marx’s main failure was to deny the intrinsic value of nature. Much of this was colored by reactions at the time to the demise of the Soviet Union and attempts to distance ecosocialism from core Marxist traditions.

Beginning in the late 1990s, these views were challenged by other ecosocialists who developed a tradition of Marxian ecology rooted primarily in the unearthing of Marx’s own ecological critique. At the center of this was Marx’s conceptualization of ecological crisis known as the theory of metabolic rift and the relationship of this to his economic value theory. Paul Burkett and I played a leading role in this reconstruction of classical Marxian ecology in Marx and Frederick Engels—Burkett in his Marx and Nature, me in Marx’s Ecology. Over the last two decades not only has our knowledge of Marx’s ecology expanded enormously, but this has been extended into a critique of contemporary capitalist ecological destruction in the work of such figures as Kohei Saito, Fred Magdoff, Andreas Malm, Brett Clark, Richard York, Ian Angus, Hannah Holleman, Del Weston, Eamonn Slater, Stefano Longo, Rebecca Clausen, Brian Napoletano, Nicolas Graham, Camilla Royle, Mauricio Betancourt, Martin Empson, Jason Hickel, Chris Williams, and a host of others. Ariel Salleh has come up with an analysis of metabolic value that integrates metabolic rift analysis with ecofeminist theory. Jason W. Moore developed a world-ecology approach that grew out of metabolic rift analysis, but eventually gravitated to posthumanism. Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro has written on socialist states and the environment.

Outside the English-speaking world, Michael Löwy has done important work in France, Daniel Tanuro in Belgium, Christian Stache in Germany, Saito and Ryuji Sasaki in Japan, Martínez-Alier and Carles Soriano in Spain, Ricardo Dobrovolski in Brazil, Eduardo Gudynas in Uruguay, and Vishwas Satgar in South Africa. In fact, ecosocialism and ecological Marxism have now spread over the entire world and influenced social movements, such as the Landless Workers’ Movement in Brazil, to the point that it is impossible to track it all. I am also aware of an enormous amount of work being done on ecological Marxism in China and have developed connections with numerous thinkers, although I am not in a position to sum up trends there. The one major work with which I am most directly familiar by a Chinese ecological Marxist is Chen Xueming’s The Ecological Crisis and the Logic of Capital (2017).

Recognition of the importance of Marxian ecology keeps on growing. Three major works in ecosocialism, Malm’s Fossil Capital (2016), Saito’s Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism (2017), and my The Return of Nature (2020), have received the prestigious Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Prize.

In terms of journals, there are very few that are directed primarily at ecosocialism. Capitalism Nature Socialism, which was founded by O’Connor and is now edited by Engel Di-Mauro, occupies a unique place. Other journals that have regularly published important ecosocialist articles include Monthly Review, where I am editor, Historical Materialism, where Malm is on the editorial board, and International Socialism, especially when Royle was editor. But ecosocialist articles appear in most socialist journals as well as academic publications. The most important ecosocialist website is Climate and Capitalism, edited by Angus.

JK: In your opinion, the relationship between human beings and the earth is our most basic material relationship, because the earth constitutes the basis for the survival and development of life. How do you view the relationship between human beings and other species in the earth community? Do you prefer anthropocentrism or ecocentrism? Do nonhuman species have intrinsic value independent of humans, or are they merely instrumental?

JBF: The relationship to the earth is, as you say, our most basic relationship, the ground of human survival and of life in general. This is fundamental to a materialist and critical-realist worldview and has to be our starting point. It is therefore important to reject an anthropocentrism based on human exemptionalism that claims that anthropogenic goals can be pursued independently of the natural-material world in which we exist. Such a view is unscientific, ethically unsound, and unecological. In that sense, we have to be ecocentric, recognizing, as Marx contended, that humanity is “a part” of nature and that we need to have a continuing dialogue with it, as the basis of our own existence. A coevolutionary and sustainable relation to nature, with the earth, is therefore essential. Ecocentrism in this sense means denying the radical separation of humanity and human society from what Marx called the “universal metabolism of nature.”

None of this means that we have to descend into certain irrational views that are sometimes associated with ecocentrism. For example, according to what is called the “new materialism,” really a revival of vitalism that is popular among some branches of the academic left in the United States, Marx is said to be “anthropocentric” in that he did not recognize that everything in existence—a stone, a lump of coal, a cloud, a microbe, a flower, a chocolate bar, a set of plastic dinosaurs—are “nonhuman persons” on the same ontological plane as human beings. This is the actual claim made by figures like Timothy Morton and Jane Bennett. Morton says that by refusing to see the coal used up in a manufacturing process as a “nonhuman person,” Marx demonstrated his alleged anthropocentrism. Obviously, to proceed along these extreme vitalistic (“new materialist”) lines is to descend into absurdity.

Indeed, Marx is sometimes criticized by thinkers like Morton for being “anthropocentric” simply for focusing on the alienation of the human-species being—as if to address human existence and the human alienation from nature in a critique of class society thereby denies the existence of other, nonhuman species beings. Yet, the truth is that Marx was strongly critical of the Cartesian mechanistic separation of human beings and animals and defended Darwinian evolution, emphasizing the human coevolutionary relation to the natural world. He also emphasized the close affinity in terms of intelligence of nonhuman animal species and human beings, and he criticized the brutality toward nonhuman animals that arose within capitalist production. Throughout his work he stressed the ecological necessity of the humanization of nature and the naturalization of humanity, that is, a coming together ecologically that superseded both the alienation of nature and the alienation of labor.

Some ecosocialists, like Kovel, have faulted Marx and Marxism for supposedly failing to incorporate the intrinsic value of nature. Here, though, we run into problems because, while we can recognize other entities/beings and their right to exist, what we call values are a human quality, a distinction that we ourselves make. Definitions of intrinsic value tend to run in circles, when attempts are made to separate it from our own judgments. Marx approached this through his concept of natural-material use values, that is, in terms of a materialist view of humanity and production that included the qualitative aspect—and the necessity—of what nature provides. He also indicated that we relate to nature not simply through our production but also sensuously, and through our conceptions of beauty, that is, aesthetically. I wrote about Marx’s ecological aesthetics and their relation to intrinsic value in the introduction to the book Marx and the Earth, coauthored with Paul Burkett. It is in our aesthetics that we connect most sensuously with nature as a whole. One of the most brilliant insights of Xi Jinping, in line with both traditional Chinese civilization and Marxism, was to recognize that the concept of ecological civilization was not quite enough, and that it needed to be supplemented by a notion of “beautiful China.” That is, our aesthetic relation to nature, and thus the intrinsic value of nature, was seen as so important that it needed to be emphasized separately.

JK: You have restored Marx as an ecologist with plenty of facts, notably by the theory of metabolic rift. Today, Marx’s ecological theory has become the basis for the development of ecological socialism. You said that a materialistic view of history has no meaning unless it is linked to a materialistic view of nature. Can you explain this in a little bit more detail?

JBF: Marx and Engels referred to their contributions to historical and social analysis as the materialist conception of history, which was viewed as a counterpart to the materialist conception of nature. The materialist conception of nature was the fundamental basis of all materialist philosophy, going back in the Western tradition to the ancient Greeks. Marx was of course an expert on ancient materialism, having written his doctoral thesis (including his seven Epicurean notebooks developed in preparation for his thesis) on Epicurus’s ancient materialist philosophy. The materialist conception of nature, as embodied particularly in Epicurus (and Lucretius), was the primary intellectual basis for the seventeenth-century scientific revolution in Europe associated with thinkers such as Francis Bacon, René Descartes, Pierre Gassendi, and Thomas Hobbes. In introducing his materialist conception of history, focusing on human social praxis, Marx therefore developed this in accord with the materialist conception of nature, aside from which historical materialism would be deprived of all real foundations. As a result, natural science concepts appear throughout Capital. The understanding of this dialectical relationship between the materialist conception of nature and the materialist conception of history is crucial to both Marxian ecology and Marxism in general.

JK: You often refer to the concept of “natural capital” in your works. Does it have the same meaning as “ecological capital”? Where does this concept stand in your critical analysis of capitalism?

JBF: I provided a historical treatment of the natural capital concept in two articles that I wrote on the “financialization of nature” for Monthly Review: “Nature as a Mode of Accumulation: Capitalism and the Financialization of the Earth” (March 2022) and “The Defense of Nature: Resisting the Financialization of the Earth” (April 2022). In these articles, I explained how the concept of natural capital was originally used beginning early in the nineteenth century to refer to natural use values by radical opponents of the capitalist economic valorization of nature, including Marx and Engels in The German Ideology. This usage continued to dominate into the 1970s and early ’80s and can be seen in the work of ecological economists E. F. Schumacher and Herman Daly. However, in more recent decades neoclassical environmental economics has transformed the concept into its opposite, changing it from one based on use value to one based on exchange value, and thus fully integrated with the capitalist economy.

From a critical concept opposed to the commodification of nature, the concept of natural capital was inverted into its exact opposite, reducing all of nature to the terms of the capitalist market. Natural capital then became the underlying concept out of which the present category of ecosystem services was developed and through which the financialization of nature is being currently promoted. In this respect, the term ecological capital is just a stand-in for natural capital, viewed in terms of exchange value. To understand the significance of this shift in analysis and why it is necessary to combat these tendencies, I recommend reading the articles mentioned above, and especially the one on “The Defense of Nature.” (It is worth noting that while Marx originally used the term natural capital, he recognized the way in which the concept could be distorted under capitalism and switched in Capital to the distinction between “earth matter” [terre-matiére] and “earth capital” [terre-capital].)

JK: The importance of ecological issues has been more and more widely recognized, and class struggle has always played an important role in classical Marxist theory. Today, do you think that the ecological crisis and the ecological struggle have gone beyond the traditional class crisis and struggle? Perhaps it would be most ideal to combine the ecological crisis and struggle with the traditional class crisis and struggle, but the two aspects do not always seem to coincide.

JBF: My way of looking at these things is somewhat different from the standard view on the left and more closely related to classical historical materialism. What you refer to here as the traditional view sees economic and ecological struggle as widely divergent from each other, with class struggle equated with economic struggle in a narrow sense. This in some ways reflects the alienated reality of contemporary capitalist society, but it certainly was not the way Marx and Engels approached the question of class. In many ways, the work that set up the whole paradigm of historical materialism was Engels’s The Condition of the Working Class in England, published in 1845. This work first introduced the notion of the Industrial Revolution, recognized the class basis of production and the phenomenon of exploitation, and also introduced the concept of the industrial reserve army of the unemployed and underemployed. It was a product in part of Engels’s own critique of political economy in the “Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy,” written in 1843, which influenced Marx in the writing of the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts. But The Condition of the Working Class was also a pioneering epidemiological work that examined the etiology of disease under capitalism, arguing that bourgeois relations of production promoted “social murder.” Therefore, Engels did not start his analysis with the exploitation of factory workers and conditions in the workplace, though that occupies part of the book, but rather with the capitalist city, housing conditions, air and water pollution, the spread of disease and illnesses of all kinds, and the much higher mortality rate of the working class. In this sense, his work was ecological as much or more than it was economic.

The struggles of the working class in the early nineteenth century were a product of their whole living conditions, not just factory conditions, even if it was their ability to stop production that was the basis of their class power. Engels wrote his book just after the so-called Plug-Plot Riots had taken place in the north of England, in the vicinity of Manchester where he was living. For Marx and Engels, working-class struggles were not restricted to strikes and battles by workers within their work sites but were also evident in the entire realm of working-class material existence. Historical materialism has too often been reduced to what we might call historical economism, leaving out wider realms of life, not only the larger environment but also the conditions of social reproduction in the household. I would also argue that it is only when class struggle extends to the entire material basis of its existence, including the workplace, the environment (both built and natural), and the conditions of social reproduction, that it is truly revolutionary. This can be applied to peasant struggles too (as Marx and Engels also recognized), though in a different way, reflecting the different class relations. Here it is clear that land or nature is always an issue, along with the control of work itself. The character of the class struggle of our times, I believe, is one of bringing together these material struggles again on a higher level so that the battles over work and the environment will increasingly become one material struggle.

JK: You believe that the major force of today’s ecological revolution is the environmental proletariat. How is this class different from the traditional proletariat? You also believe that the struggle of the working class in developed countries is not as strong as that of the working class in less developed countries because the former are the indirect beneficiaries of the global imperialist system. But the Southern proletariat may also benefit from the employment, income, and other opportunities that this system brings. In reality, have they shown themselves to be more revolutionary compared with the Northern proletariat?

JBF: The notion of the environmental proletariat is really an attempt to get back to both the classical historical-materialist notion of the proletariat in Marx and Engels’s thought, and also to develop a notion of the planetary proletariat appropriate to our times. The basic idea is that human beings are dependent on the material conditions of their existence and their struggles to develop their human capacities in that context. But these material conditions are not narrowly economic but also ecological/environmental, and thus more all-encompassing. What is involved in class struggle today is not simply struggles in the workplace, though, as always, this is the center of working-class power, but also struggles over the whole environment. It is becoming more and more difficult to separate the economic and environmental conditions of material existence. If there is a shortage of food or water available to the population in the Global South today, is this due primarily to economic or ecological factors? The fact is that such problems are more and more intertwined given the structural crisis of capital and combined economic and ecological crisis and catastrophe.

The economic proletariat has often been constrained by the logic of trade unions and the struggle for wages and benefits. The environmental proletariat, which is simply a way of referring to the proletariat in terms of the full complexity of its material existence, is concerned with work relations but also the full range of material life conditions. Such a unified standpoint is necessarily more revolutionary and more capable of grappling with the problems of the age. The true revolutionary struggle, as István Mészáros argued, required the transformation of the entire system of social metabolic reproduction, currently dominated in an alienated way by capital. To speak of an environmental proletariat is thus to speak of a broader proletariat, the coming together of environmental and economic concerns, of proletarians, peasants, and the Indigenous. It means dealing with issues of social reproduction under capitalism that have led to extreme gender-based oppression of women. We can already see a broader environmental proletarian consciousness emerging in places throughout the world, especially in the Global South, where conditions are more serious—especially wherever socialism is developing. Development of an environmental proletarian consciousness will determine the ability of populations to respond to the age of planetary crisis with which we are already confronted. This struggle is inevitable and is already coming into being.

In terms of the question of the more revolutionary character of workers in the Global South, there cannot be the slightest doubt. It is the workers in the periphery of the capitalist system who are faced with the sharp edge of imperialism. We have the entire twentieth century and the first two decades of the twenty-first century testifying to the revolutionary struggles on every continent of the Global South. Revolutions have been a continuous feature in the monopoly capitalist era, even if largely absent from the core of the capitalist society in the Global North/West. Not all of these revolutions have succeeded, of course. They have been confronted in every case by the forces of counterrevolution—in the post-Second World War era represented chiefly by the United States backed by the other imperial powers. Nevertheless, it is the proletariat/peasantry in the Global South that has continually led the way, and where one consequently sees the most radical environmental-proletarian struggles today. In terms of the understanding of this whole development, one of my favorite books, even though now out of date, is L. S. Stavrianos’s The Global Rift: A History of the Third World.

JK: Capitalism, because of its logic of profit, can only be doomed in the end. You even say that imagining the end of capitalism has become easier than imagining the end of the world. But isn’t that too optimistic? Although, as you said, the world has fallen into the era of catastrophe capitalism, which is manifested by global ecological crisis, global epidemic crisis, and endless world economic crisis, the power of capitalism seems to be still strong today.

JBF: I previously said (see the discussion of this in “The Planetary Rift” in the November 2021 issue of Monthly Review) that we were now moving away from the hegemony of “capitalist realism,” that is, the notion, critically articulated by Fredric Jameson twenty years ago, that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.” I first indicated in March 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic was beginning, that this was now being reversed. In this respect, I inverted Jameson’s famous statement, saying: “It has suddenly become easier to imagine the end of capitalism than the end of the world.” What I meant is that in the face of the crises and catastrophes emerging in our time—such as economic stagnation and financialization (including the 2008 financial crisis), COVID-19, climate change, the resurrection of fascist movements around the world, and the beginnings of a New Cold War—populations everywhere are increasingly becoming aware that capitalism has failed. The general collapse of what had seemed a stable social order is more and more seen in terms of the structural crisis of capitalism, and not simply in terms of the advent of a dystopian or apocalyptic future.

Once again, consciousness of what Marx called the “tragic flaw,” represented by the alienated society of capitalism, is coming to the fore in the consciousness of people everywhere, leading to growing demands to overcome the existing social relations and the mode of production. This is not overly optimistic since it is happening all around us, even if the final outcome of the struggle over capitalism is far from certain. Bernie Sanders’s new book is called It’s OK to Be Angry about Capitalism. This represents a big shift from what Jameson was referring to twenty years ago.

JK: According to your research, has the global ecological movement in recent years held back the ecological imperialism of Western developed countries? Has the Global North’s ecological debt to the Global South been diminished? What are the impediments?

JBF: The global environmental movement, which is today growing very rapidly, has made an enormous difference in resisting and slowing down the capitalist juggernaut. But the ecological debt owed to the Global South can hardly be said to have diminished, as ecological imperialism is being extended even in the context of the planetary ecological emergency.

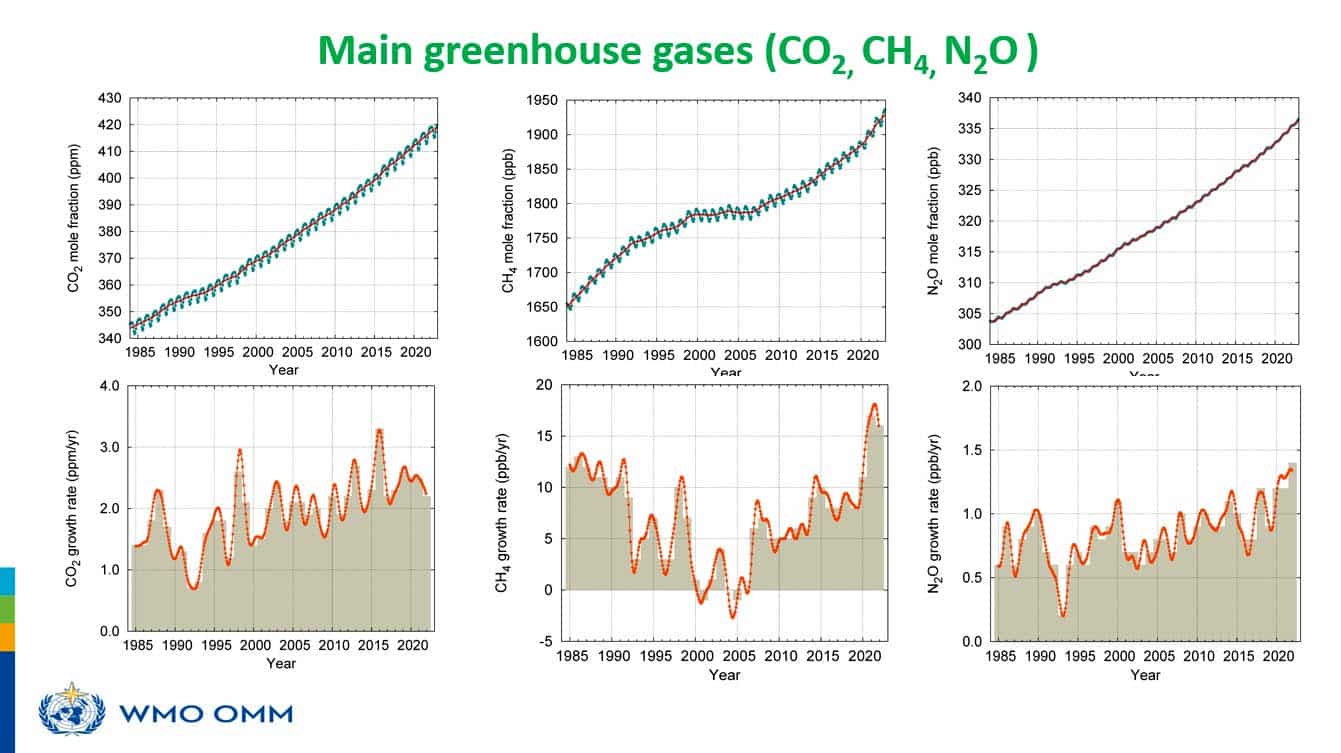

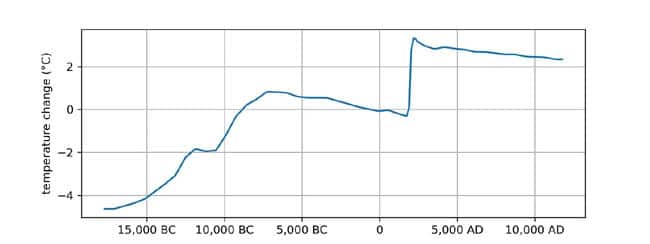

To get a sense of the scale of the problem, we can look at what is owed to the Global South in terms of the global carbon budget. Science has established a global carbon budget based on a target of 350 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Once the carbon budget was established it was possible to determine what the fair share of carbon emissions on a per capita basis would be for each country. As Jason Hickel demonstrated in an important study in Lancet Planetary Health in September 2020, if we subtract the actual emissions of countries from their fair share, we can then determine which countries have, in their historical emissions, generated excess or surplus emissions. What Hickel was able to determine based on 2014 data was that 40 percent of all excess carbon dioxide emissions in the world added to the atmosphere were attributable to the United States, and 92 percent to the rich nations of the Global North. Meanwhile, China and India both had zero excess emissions. The excess emissions of the countries of the Global North represent an enormous ecological debt in the form of a climate debt to the Global South.

This of course does not account for all the other ways in which the Global North over the last five centuries or more has generated an ecological debt to the Global South. And yet, the rich countries, rather than aiding the poor countries, are extending their overall ecological imperialism, something that Hannah Holleman, Brett Clark, and I addressed in an article entitled “Imperialism in the Anthropocene” in Monthly Review in July–August 2019.

JK: Some scholars believe that the socialist development model is also subject to economic rationality and cannot avoid ecological destruction. James O’Connor says, for example, that the same systematic force is as effective in the East as it is in the West. What do you think about this? What are the advantages of socialism to overcome the ecological crisis?

JBF: I am not aware of any place where O’Connor said that the same systematic forces applied in both the East and West, though he may have said this somewhere. For him, the East would have no doubt have referred primarily to the Soviet Union/Russia. O’Connor saw the conditions that prevailed in Soviet-type societies as quite different from that of Western capitalism, although there was a lot of overlap in terms of technology, emphasis on industrialization, etc. His analysis in this respect was very sophisticated and is worth reading today, particularly his introduction to part 3 on “Socialism and Nature” in his book Natural Causes. Socialism arises out of capitalism and thus is inherently infected by many of its contradictions. The world-economy as a whole is capitalist, which means that socialist countries have to navigate their way through all sorts of external contradictions imposed on them, not least of all imperialist pressures. Nevertheless, what differs between countries who are socialist (or postrevolutionary) and capitalist are the social relations of production, which open up all sorts of new opportunities. China, for example, though beset with ecological problems, has been able to develop modes of ecological management and planning that would be unthinkable in the Global North/West.

JK: Although China has the largest annual carbon emissions in the world today, much of it is used to produce commodities for Western consumption, and China’s historical carbon emission and per capita emission are far lower than those of developed countries in Europe and the United States. Nevertheless, China has made it clear that it wants to follow a path of ecological civilization and has laid out a road map for carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. You also believe that China’s efforts to build an ecological civilization are revolutionary. In your opinion, what should China emphasize to tackle the ecological crisis and build an ecological civilization?

JBF: China’s approach to building an ecological civilization is radically different from anything that exists in the West/Global North. Xi has made it clear that the goal is to alter the whole “developmental model and way of life. [This means] establishing a sound economic structure that facilitates green, low-carbon and circular development…promoting a thorough transition towards eco-friendly economic and social development” as “fundamental solutions to China’s eco-environmental problems.” (See his speech, “Achieve Modernization Based on Harmony Between Man and Nature,” April 30, 2021.) This is achieving startling results. For example, China’s newly added vegetative ground cover between 2000 and 2017, according to the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), was one-quarter of the planetary total. The Fourteenth Five-Year Plan (2021–25) makes a reduction in carbon dioxide emissions a priority, with China planning to peak its carbon emissions before 2030 during its Fifteenth Five-Year Plan (2026–30) and to reach net zero emissions by 2060. China has become the world leader in green technology and production.

The big issue remains coal. Although the share of coal-fired plants in China’s energy consumption has dropped from 70 percent to around 56 percent, China in the last two years has increased its coal mining and has been building new coal-fired plants. It has reached new records of overall coal consumption, even though such consumption had been relatively flat over the last decade. Some have interpreted this as China’s retreat from its goals of peaking carbon emissions and reaching carbon neutrality. However, the reality is much more complex than that, as Beijing is seeking to balance energy stability and energy security with lower levels of pollution and carbon emissions. Power shortages in some regions and new concerns with respect to energy security led the government to develop a new role for coal—consistent, in its view, with the long-term phasing down of coal consumption and the eventual elimination of unabated coal capacity (lacking carbon capture and sequestration). Coal power generation is seen as essential to support the power grid throughout the country, even as a rapid shift is made toward alternative energy. Coal-fired plants, once built, can be designed to run at lower capacity in normal circumstances, while capacity utilization can be increased when needed to stabilize energy production. There is thus a focus on using coal as a reserve capacity. In this way, an increase in the number of coal-fired plants in China could actually support a shift away from coal. New plants are also designed to replace former coal plants that are less efficient (primarily affecting pollution reduction). Since China plans to reach peak carbon emissions during the next five-year plan, from 2026 to 2030, it will be necessary for it to take strenuous measures to level off and reduce its coal emissions this decade.

A big factor in China’s continuing reliance on coal has to do with energy security, not simply economics. Coal is the only fossil fuel that China has in abundance. With the United States launching a New Cold War on China during the Donald Trump administration, which has been carried forward and intensified under the Joe Biden administration, energy security has become a bigger issue for China. As Xi put it in a speech in October 2021, China “must hold the energy food bowl in its own hands.” In this respect, Beijing is very conscious of the whole history of imperialism and how Western powers had imposed sanctions on it during the century of Western “gunboat” interventions enforcing unequal treaties, something that only ended with the Chinese Revolution.

It is important to remember that, although China is the leading emitter of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere today, its national responsibility for the overall problem is much less than that of countries in the Global North, who are the main carbon debtors in per capita terms. As Hickel showed, and is mentioned above, China, as of 2014 data, had zero excess historical emissions (in per capita terms), while the United States accounted for 40 percent of the world total.

JK: Some scholars argue that China’s emphasis on ecological civilization has little to do with ecological Marxism, but is mainly rooted in traditional Chinese culture, which could be traced back to the idea of “unity of nature and man” thousands of years ago. You do not seem to agree with that. What is the role of ecological Marxism in the construction of ecological civilization in China in your opinion?

JBF: I dealt with this in my article “Ecological Civilization, Ecological Revolution,” originally a talk to a group of Chinese scholars, that appeared in the October 2022 issue of Monthly Review. In that talk I was countering Jeremy Lent, who argued that ecological civilization grew entirely out of traditional Chinese values and had nothing to do with ecological Marxism. In response, I pointed out that the concept of ecological civilization had its origin within Marxism itself in the Soviet Union in its final decades and had been adopted at the time by Chinese ecological Marxists, only to be developed further over the last three decades in China. Attempts to dissociate it from Marxism were thus historically incorrect.

Yet, I also argued that the notion of ecological civilization was developed in China as part of an ecological Marxism with Chinese characteristics, drawing on China’s own vernacular revolutionary tradition and thus on traditional Chinese culture. Rather than looking at ecological Marxism and the traditions of Chinese culture as simply separate, even antagonistic, this view reflects their close relationship in many respects where ecological considerations apply.

My way of thinking about this was very much influenced by the work of the great Marxist scientist and leading Western Sinologist Joseph Needham, the principal author of the massive multivolume Science and Civilization in China. I wrote about Needham in my book The Return of Nature. There is an interesting popular biography of him by Simon Winchester entitled The Man Who Loved China. In contrast to Lent, who designates Western culture and science as geared from the first to the outright domination and expropriation of nature, Needham emphasized how scientific humanism and organic naturalism in the West emerged out of ancient Epicurean materialism, which had a profound influence on Marx’s thought. Epicureanism and Daoism had a certain resemblance. “Lucretius,” he wrote, “spoke the same language [in this respect] as the Taoists.” The Daoist concept of wu wei or nonaction was not about passivity, but about avoiding actions that were “contrary to nature.” Central to Daoism is the conception of “production without possession, action without self-assertion, development without domination.” All of this had a natural affinity with dialectical materialism. “Organic naturalism,” Needham observed in Within the Four Seas, “was the philosophia perrenis of China.” Chinese thinkers might therefore see Marxist dialectical materialism as the return of their “own philosophia perennis integrated with modern science, and [which had] at last come home.”

My own thinking has been heavily influenced by P. J. Laska’s The Original Wisdom of the Dao De Jing: A New Translation and Commentary. There we read:

The ruling houses deduct too much, the

granaries are empty and the fields are

overgrown with weeds. At court they wear

richly designed silk clothing, carry weapons,

gorge themselves with food and drink, and

have an excess of wealth and possessions.

This is called “robbers boasting.”

It is certainly not the Way!

Here it is worth mentioning that Marx was not unaware of Eastern philosophy and had a considerable interest in Buddhism. The great Indian Marxist scholar Pradip Baksi has explored Marx’s interest in the Buddhist concept of nothingness.

JK: The developed capitalist countries are also engaged in a practical struggle for the sustainable development of humankind. You have mentioned that Cooperation Jackson in Mississippi is engaged in a revolutionary project as part of building ecosocialism. Would you please tell us something about the activities of this organization or other similar organizations?

JBF: In our special issue of Monthly Review on “Socialism and Ecological Survival” in July–August 2022, we were concerned with issues of how communities can organize on an ecosocialist basis for survival, given the fact that environmental devastation is now accelerating due to climate change. One such community organization that Brett Clark and I looked at in our introduction to the issue was Cooperation Jackson. Rather than being a way in which the state or capital are engaged in struggles for sustainable development in a developed capitalist society, Cooperation Jackson is a revolutionary ecosocialist federation of cooperatives led by and largely geared to the needs of African-American and Latinx communities that is arising out of the most racially oppressed populations in the country and within the working class. They emphasize sustainability, social justice, and a just transition with respect to the environment as well as collective needs and were initially inspired by the Mondragon experiment in Spain. We regard Cooperation Jackson as one of numerous organizations within the pores of capitalist society arising from working-class and oppressed frontline communities that represent a way forward for the environmental proletariat within the belly of the beast. Although small at present, such movements constitute islands of revolutionary hope and action that prefigure an alternative future.

JK: In a series of works, you have described the terrifying scenario of a nuclear winter. If thermonuclear war did occur, global temperatures could drop dramatically, with devastating consequences for life on Earth. Since the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war, the world has turned its attention to the possibility of war between nuclear powers, which means a shift from carbon extinction to nuclear extinction. How do you see the possibility of nuclear war?

JBF: It is not a problem so much of “a shift from carbon extinction to nuclear extinction,” but rather a problem of two possible extinctions of humanity facing us that are closely related. Accelerated climate change or global warming is a result of emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere inducing rising average global temperatures. A global thermonuclear exchange, by pouring smoke and soot into the atmosphere, thereby generating nuclear winter, operates in the opposite direction, but virtually overnight. Both processes came to be understood almost simultaneously by climate scientists in the Soviet Union and the United States. Today we are thus facing the threat of two exterminisms. The destabilization of the world environment by climate change has in some ways, ironically, accelerated the competition over energy resources globally, intensifying the conflict between the nuclear superpowers and thus the possibility of nuclear winter.

When the Ukraine War heated up in 2022, it became clear to me that the most important issue for humanity as a whole in this conflict was that the most dangerous proxy war ever to take place was putting the nuclear superpowers on the verge of a global thermonuclear exchange. Nevertheless, the very real dangers of this were not clearly understood even on the left, since most people had stopped paying attention to nuclear war planning after 1991 and the dissolution of the USSR, and had long since put their faith in mutual assured destruction (MAD) as a kind of absolute deterrence.

Taking a cue from E. P. Thompson, the great English Marxist historian and leader of the European Nuclear Disarmament movement in the 1980s, who had written an essay on “Notes on Exterminism” dealing with the dangers of nuclear war (and environmental destruction), I wrote an article in the May 2022 issue of Monthly Review on “‘Notes on Exterminism’ for the Twenty-First Century Ecology and Peace Movements.” That article was organized around two themes. One, climate science research this century had further confirmed the nuclear winter analysis developed in the 1980s, indicating that massive fires engendered in a hundred cities due to a thermonuclear exchange would result in so much smoke and soot being added to the atmosphere that solar radiation would be blocked and global average temperatures would fall to the extent that it would kill almost all of humanity on the planet in a few years. Two, the debate on nuclear weapon development in the United States following the demise of the USSR had led to a victory of the maximalists over the minimalists, resulting in the concerted pursuit of counterforce weapons designed to provide the United States with “nuclear primacy” or first-strike capability—through the decapitation of the nuclear weapons on the other side before they could be launched, and the picking off of what remained with anti-ballistic missile systems—even in relation to major nuclear powers such as Russia and China.

In 2007, the U.S. foreign and military establishment announced that U.S. global “nuclear primacy” was on the brink of being achieved. This meant that the U.S. strategic nuclear posture was no longer restricted by the notion of MAD, but rather was seen in terms of nuclear primacy or first-strike capability—a dangerous illusion, but one that increasingly drove Washington’s policy, leading to a new military aggressiveness in recent years, particularly in the face of declining U.S. hegemony. For example, the United States believes that China’s nuclear submarine fleet is non-survivable in a U.S. first strike, since China has not yet been able to reduce the noise level of its submarines sufficiently to avoid detection (though its achievements in this respect in recent years have been remarkable). Russian and Chinese missile silos are increasingly vulnerable to more accurate missile targeting, even by non-nuclear missiles. All of this has encouraged heightened U.S. belligerence, which was long constrained by MAD. Washington is pushing the world dangerously toward nuclear war in its effort to decrease its declining hegemony, particularly due to the rise of China—and so as to achieve its (impossible) goal of a U.S.-dominated unipolar world. Needless to say, Russia and China have been taking actions in response, such as the development of hypersonic missiles. As a consequence of all of this, the revival of the world peace movement is an urgent task.

JK: We note that you recently collaborated with other scholars on a new book, Washington’s New Cold War: A Socialist Perspective. Would you please tell us something about it?

JBF: That book, published by Monthly Review Press together with the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research, consists of three essays: the essay on “‘Notes on Exterminism’ for the Twenty-First Century Ecology and Peace Movements” by me, mentioned above, and two essays, written on the New Cold War, both of which we first published in Guancha in China and then on MR Online: John Ross’s “What Is Propelling the United States Into Increasing Military Aggression?” and Deborah Veneziale’s “Who Is Leading the United States to War?” Vijay Prashad wrote an introduction to the book.

The essays in the book depict the U.S. role in engendering a New Cold War. Since the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991, the United States, according to the Congressional Records Office, has carried out more military interventions/wars in other countries than in its entire previous history. It has enlarged NATO so that it now encompasses the territory of nearly all the former Warsaw Pact nations and regions of the former Soviet Union. This expansion has led to the present Ukraine War. At the same time, Washington has declared that China is its number one security threat, due to the challenge that China’s growth presents to the “international rules-based order,” or the institutions of U.S.-based global power (and that of the triad of the United States/Canada, Europe, and Japan).

The United States is currently threatening the People’s Republic of China over Taiwan, which is internationally recognized—by the United States as well—as part of China, but with a different system, in accord with the One China Principle. Beijing’s long-term goal of the reunification of the populations on the two sides of the Taiwan strait, in accordance with the One China policy, has been distorted by Washington into a case of imminent aggression by Beijing and a potential causus belli. Beijing’s own position is that this is an internal matter within China itself. Under the Biden administration, U.S. military forces stationed in Taiwan are being quadrupled. The United States currently has four hundred military bases surrounding China in what is often referred to as a giant noose.

In the context of declining U.S. economic hegemony, Washington is insisting on a unipolar world, promoting military blocs aimed at China and Russia, and rejecting the actual multipolar development of the world at large, through the development of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). The U.S. dollar’s role as the international reserve currency is being weaponized to sanction both Russia and China, along with all other nations that have challenged U.S. dominance, while the triad continues to seek to wield its imperial dominance over all three continents of the Global South. The world is therefore on the edge of a Third World War, threatening the very existence of humankind. China’s response has been to launch in 2022 its Global Security Initiative, which constitutes the most comprehensive set of commitments for overall world security, including the security interests of all nations, that has ever been introduced, arising out of a long tradition that in the West goes back to Immanuel Kant’s essay on “Perpetual Peace.”

This is the era of the Great Choice. The world will either move in the direction of socialism and world peace or toward an even more barbaric capitalism (that is, fascism) and exterminism. It is Mészáros who most deserves credit for emphasizing this in 2001 in his Socialism or Barbarism: From the “American Century” to the Crossroads. There he wrote: “If I had to modify Rosa Luxemburg’s dramatic words, in relation to the dangers we now face, I would add to ‘socialism or barbarism’ this qualification: ‘barbarism if we are lucky.’ For the extermination of humanity is the ultimate concomitant of capital’s dangerous course of development,” which now confronts us in “the potentially most dangerous phase of imperialism.”

https://socialistchina.org/2023/10/18/j ... l-marxism/