The Long Ecological Revolution

Re: The Long Ecological Revolution

Sustainable Consumption: A view from the Global South

Posted Jun 09, 2021 by Eds.

Agriculture , Capitalism , Ecology , Environment Global Newswire Consumption , Sustainability

Originally published: Social and Political Research Foundation by Nikhil Varghese Mathew (June 5, 2021) |

The global discourse on sustainability has revolved around the need to transition towards “Sustainable Consumption” ever since it was introduced during the 1992 Earth Summit chaired by Maurice Strong, a Canadian businessman who made his wealth from the oil and gas industry. A couple of years later, the 1994 Oslo Symposium on “Sustainable Consumption” sought to resolve the ambiguities around the term’s definition and decided to define it as: “the use of goods and services that respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life, while minimising the use of natural resources, toxic materials and emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle, so as not to jeopardise the needs of future generations.” (United Nations Sustainable Development Goals n.d.).

However, mainstream developmental approaches have espoused, both in theory and practice, an ideological foundation for sustainable consumption that is ignorant of the societal conditions enmeshed with production relations.1 Instead, the effort is merely towards perpetuating ‘business as usual’. In seeking to posit individual consumption practices as being fundamentally at odds with sustainability, and in seeking to obfusticate the ontological interconnectedness between nature and society by supposing a dichotomous relationship between human development and the environment, “sustainability” (as is conceptualised by mainstream narratives) both decontextualises and ahistoricises socio-ecological interdependencies and extant material power relations (Dolan 2002).

This is evidenced by the following extract from the ‘Agenda 21’ report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. The section on ‘Recognizing and Strengthening the Role of Indigenous People and their Communities’ notes:

International development agencies and Governments should commit financial and other resources to education and training for indigenous people and their communities to develop their capacities to achieve their sustainable self-development, and to contribute to and participate in sustainable and equitable development at the national level. (United Nations 1993).

Encouraging modes of development centered around the Global North and consequently free market arrangements, implies credence to the argument made that prevalent policy narratives around broader rubrics of developmental financing and sustainability are designed to allow capital and its advocates thereof to advocate for and lend legitimacy to the paradigm of “nature as capital” (Liodakis 2010; Foster 2014).

Impediments to capital accumulation are overcome through incentivising investments for previously nonexistent natural resource frontiers2 (Sweezy 1967). Thinkers from the Global South thought have gone on to critique the role of multilateral agreements in commodifying nature, with scholars such as Archana Prasad stating in light of the REDD-Plus regime3 and the perpetuation of ‘green capitalism’4 that “REDD-Plus became a vehicle for promoting green capitalism in the wake of a severe capitalist crisis and the need to address concerns regarding dipping profits of corporations” (Prasad 2020).

The global economy has become the field of activity for giant corporations that control over 80% of world trade, where the production chain of commodities is fragmented into multiple links spread across the globe (Wiedmann et al., 2015). The fundamental restructuring of global production and trade networks that has accompanied efforts to entrench green capitalism has resulted in immiseration and expropriation of communities instead of achieving the stated aim of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Through construing nature as “one vast gasoline station” (Harvey 2015) green capitalism and market environmentalism allows for practices such as corporate greenwashing that undermine efforts towards transcendental change, whilst concomitantly working “to shift the focus from the firm, create confusion, undermine credibility, criticize valuable alternatives, and deceptively promote the firm’s objectives” (Budinsky and Bryant 2013). Green capitalism necessitates reinforcing the conception of the non-human as an externality, placing the onus on the individual as an entity removed and disembodied from the larger matrix of societal phenomenon that produces consumption and production practices. Therefore, under the logic of contemporary production relations, precedence is accorded to micro-level behavioural changes as opposed to larger, structural issues that stitch together all aspects of modern living.

The centralisation of capital, as alluded to in this paper, and the expansion of the “world market,” is built around the need for multinational corporations to access larger markets, inexpensive labour and cheap sources of raw material (Suwandi et al., 2019). The process of the global expansion of capital, headquartered in the Global North, was restrained during the post-second world war period. This restraint has now disappeared with the reintroduction of the spontaneity of the system, resulting in the strengthening of the centralisation of capital on a global scale (Patnaik 2018). Thus, it is argued that the cornerstone of interactions between nation states, at the present stage of industrial development, is the inescapable reality that “a few major corporations from a small number of countries dominate the world market,” wherein through the significant movement of capital from the Global North to the Global South, we see a decentering of production across sectors (Suwandi 2019).

Decentering of production allows, through the restrictions placed on the mobility of labour and a contrasting free mobility accorded to capital, the drain of economic surplus from the global South by holding down wages (Patnaik and Patnaik 2015). In 2012 alone, the net flow of resources to the global North from developing economies was estimated to amount to USD $2 trillion (Suwandi et al., 2019). This exemplifies how multinational corporations are “sucking out the surplus of an economy without any quid pro quo” (ibid.) by higher rates of exploiting labour in the Global South, establishing globalisation of production upon the basis of wide wage differentials between central and periphery economies. Differentials that far exceed their differences in productivity.

The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference is set to take place in Glasgow from the 1st November 2021. In light of this, it is important to reiterate that any genuine and effective exercise in sustainability must be predicated upon broad-ranging equity and social justice, while acknowledging and transcending problems presented by models of mainstream economic growth and development. The much-touted European Commission (2019) strategy document ‘Going Climate-Neutral by 2050’ outlines four axes of policy actions said to be necessary for ensuring carbon neutrality. Points two and three refer to the need to “scale up private investments” and to “provide the right signals to markets”. The strategy demonstrates the developed world’s preoccupation with pursuing ‘business as usual’, which can no longer be allowed to preempt all genuine efforts to arrest climate change.

Edited by: Riya Singh Rathore and Priyamvada Chaudhary

Notes:

↩ Production relations here refers to the relationship between people structured by their ownership of either capital or labour power. Within a system of generalised commodity production, these relations of production are mediated by caste, patriarchy, and racism among other social cleavages. While these can be said to be pre-capitalist forms of exploitation, the logic of contemporary production relations results in their accomodation within the market economy, effectively resulting in a situation wherein the broad underclass of the socio-economically deprived subsidises costs of production.

↩ As seen in the neoliberalistion/ commodification of nature. For instance the commodification of the atmosphere in itself as a form of capital in the creation of carbon credits.

↩ Refer here for additional reading on the issue.

↩ Green Capitalism is the systematic belief that nature’s inherent value is in the monetary profit it makes. This approach is contradictory in nature since although it speaks of the “green” agenda, which implies putting a stop to depletion of Earth’s resources brought about by the “madness of economic reason”, it also advocates for capitalism, a system of accumulation which accounts for nature as a mere input to the accumulation of capital. Refer here for additional reading on the topic.

References

Budinsky, Jennifer and Susan Bryant. (2013). ““It’s Not Easy Being Green”: The Greenwashing of Environmental Discourses in Advertising.” Canadian Journal of Communication 38: 207-226.

Dolan, Paddy. (2002). “The Sustainability of “Sustainable Consumption.” Journal of Macromarketing 22 (2): 170-81.

European Commission. (2019). Going Climate-neutral By 2050: A Strategic Long-term Vision for a Prosperous, Modern, Competitive and Climate-Neutral EU Economy. Luxembourg: Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Foster, John Bellamy. (2014). “Paul Burkett’s Marx and Nature Fifteen Years After.” Monthly Review 66 (7). Accessed 28 May 2021, monthlyreview.org.

Harvey, David. (2015). Seventeen Contradictions And The End Of Capitalism. London, United Kingdom: Profile Books.

Liodakis, George. (2010). “Political Economy, Capitalism and Sustainable Development.” Sustainability 2(8): 2601-2616.

Patnaik, Utsa and Prabhat Patnaik. (2015). “Imperialism in the Era of Globalization.” Monthly Review 67(3). Accessed 29 May 2021, monthlyreview.org.

Patnaik, Prabhat. (2018). “Globalization and the Peasantry in the South.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 7(2): 234-248.

Prasad, Archana. (2020). “Ecological Crisis, Global Capital And The Reinvention Of Nature: A Perspective From The Global South.” In Rethinking The Social Sciences With Sam Moyo edited by Praveen Jha, Paris Yeros, and Walter Chambati. New York, United States of America: Columbia University Press.

Suwandi, Intan. (2019). “Labor-Value Commodity Chains: The Hidden Abode of Global Production.” Monthly Review 71 (3). Accessed 27 May 2021, monthlyreview.org

Suwandi, Intan, R. Jamil Jonna, and John Bellamy Foster. (2019). “Global Commodity Chains And The New Imperialism.” Monthly Review 70 (10). Accessed 28 May 2021, monthlyreview.org

Sweezy, Paul. M. (1967). “Rosa Luxemburg’s ‘The Accumulation of Capital’.” Science & Society 31 (4): 474-485.

United Nations. (1993). Report Of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. New York, United States of America: United Nations.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. (n.d.). “Sustainable consumption and production.” Accessed 1 June 2021, sustainabledevelopment.un.org.

Wiedmann, Thomas, Heinz Schandl, Manfred Lenzen, Daniel Moran, Sangwon Suh, James West, and Keiichiro Kanemoto. (2015). “The Material Footprint Of Nations.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (20): 6271-6276.

https://mronline.org/2021/06/09/sustain ... bal-south/

"Globalization" is a business model and does not represent the totality of political reality. The nation state ain't going nowhere, at least not 'the players' though the less robust will be recolonized by financial arrangements. Because when the going get rough and the talk seems to run out there must be a resort to force. Serious standing military force is very expensive, a cost no corporation wishes to bear. And so these costs are outsourced with the corps paying little or any and profiting mightily. Why would they give up that?

A resumption of imperialist competition, on hiatus since the end of WWII, will be the inevitable result of the decline of US hegemony. Globalization has been an economic manifestation of that hegemony, it could not happen unless the US based corporation profited thereby. The US is not interested in sharing those profits with China or anyone else. As that hegemony declines the cracks will show.

Posted Jun 09, 2021 by Eds.

Agriculture , Capitalism , Ecology , Environment Global Newswire Consumption , Sustainability

Originally published: Social and Political Research Foundation by Nikhil Varghese Mathew (June 5, 2021) |

The global discourse on sustainability has revolved around the need to transition towards “Sustainable Consumption” ever since it was introduced during the 1992 Earth Summit chaired by Maurice Strong, a Canadian businessman who made his wealth from the oil and gas industry. A couple of years later, the 1994 Oslo Symposium on “Sustainable Consumption” sought to resolve the ambiguities around the term’s definition and decided to define it as: “the use of goods and services that respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life, while minimising the use of natural resources, toxic materials and emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle, so as not to jeopardise the needs of future generations.” (United Nations Sustainable Development Goals n.d.).

However, mainstream developmental approaches have espoused, both in theory and practice, an ideological foundation for sustainable consumption that is ignorant of the societal conditions enmeshed with production relations.1 Instead, the effort is merely towards perpetuating ‘business as usual’. In seeking to posit individual consumption practices as being fundamentally at odds with sustainability, and in seeking to obfusticate the ontological interconnectedness between nature and society by supposing a dichotomous relationship between human development and the environment, “sustainability” (as is conceptualised by mainstream narratives) both decontextualises and ahistoricises socio-ecological interdependencies and extant material power relations (Dolan 2002).

This is evidenced by the following extract from the ‘Agenda 21’ report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. The section on ‘Recognizing and Strengthening the Role of Indigenous People and their Communities’ notes:

International development agencies and Governments should commit financial and other resources to education and training for indigenous people and their communities to develop their capacities to achieve their sustainable self-development, and to contribute to and participate in sustainable and equitable development at the national level. (United Nations 1993).

Encouraging modes of development centered around the Global North and consequently free market arrangements, implies credence to the argument made that prevalent policy narratives around broader rubrics of developmental financing and sustainability are designed to allow capital and its advocates thereof to advocate for and lend legitimacy to the paradigm of “nature as capital” (Liodakis 2010; Foster 2014).

Impediments to capital accumulation are overcome through incentivising investments for previously nonexistent natural resource frontiers2 (Sweezy 1967). Thinkers from the Global South thought have gone on to critique the role of multilateral agreements in commodifying nature, with scholars such as Archana Prasad stating in light of the REDD-Plus regime3 and the perpetuation of ‘green capitalism’4 that “REDD-Plus became a vehicle for promoting green capitalism in the wake of a severe capitalist crisis and the need to address concerns regarding dipping profits of corporations” (Prasad 2020).

The global economy has become the field of activity for giant corporations that control over 80% of world trade, where the production chain of commodities is fragmented into multiple links spread across the globe (Wiedmann et al., 2015). The fundamental restructuring of global production and trade networks that has accompanied efforts to entrench green capitalism has resulted in immiseration and expropriation of communities instead of achieving the stated aim of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Through construing nature as “one vast gasoline station” (Harvey 2015) green capitalism and market environmentalism allows for practices such as corporate greenwashing that undermine efforts towards transcendental change, whilst concomitantly working “to shift the focus from the firm, create confusion, undermine credibility, criticize valuable alternatives, and deceptively promote the firm’s objectives” (Budinsky and Bryant 2013). Green capitalism necessitates reinforcing the conception of the non-human as an externality, placing the onus on the individual as an entity removed and disembodied from the larger matrix of societal phenomenon that produces consumption and production practices. Therefore, under the logic of contemporary production relations, precedence is accorded to micro-level behavioural changes as opposed to larger, structural issues that stitch together all aspects of modern living.

The centralisation of capital, as alluded to in this paper, and the expansion of the “world market,” is built around the need for multinational corporations to access larger markets, inexpensive labour and cheap sources of raw material (Suwandi et al., 2019). The process of the global expansion of capital, headquartered in the Global North, was restrained during the post-second world war period. This restraint has now disappeared with the reintroduction of the spontaneity of the system, resulting in the strengthening of the centralisation of capital on a global scale (Patnaik 2018). Thus, it is argued that the cornerstone of interactions between nation states, at the present stage of industrial development, is the inescapable reality that “a few major corporations from a small number of countries dominate the world market,” wherein through the significant movement of capital from the Global North to the Global South, we see a decentering of production across sectors (Suwandi 2019).

Decentering of production allows, through the restrictions placed on the mobility of labour and a contrasting free mobility accorded to capital, the drain of economic surplus from the global South by holding down wages (Patnaik and Patnaik 2015). In 2012 alone, the net flow of resources to the global North from developing economies was estimated to amount to USD $2 trillion (Suwandi et al., 2019). This exemplifies how multinational corporations are “sucking out the surplus of an economy without any quid pro quo” (ibid.) by higher rates of exploiting labour in the Global South, establishing globalisation of production upon the basis of wide wage differentials between central and periphery economies. Differentials that far exceed their differences in productivity.

The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference is set to take place in Glasgow from the 1st November 2021. In light of this, it is important to reiterate that any genuine and effective exercise in sustainability must be predicated upon broad-ranging equity and social justice, while acknowledging and transcending problems presented by models of mainstream economic growth and development. The much-touted European Commission (2019) strategy document ‘Going Climate-Neutral by 2050’ outlines four axes of policy actions said to be necessary for ensuring carbon neutrality. Points two and three refer to the need to “scale up private investments” and to “provide the right signals to markets”. The strategy demonstrates the developed world’s preoccupation with pursuing ‘business as usual’, which can no longer be allowed to preempt all genuine efforts to arrest climate change.

Edited by: Riya Singh Rathore and Priyamvada Chaudhary

Notes:

↩ Production relations here refers to the relationship between people structured by their ownership of either capital or labour power. Within a system of generalised commodity production, these relations of production are mediated by caste, patriarchy, and racism among other social cleavages. While these can be said to be pre-capitalist forms of exploitation, the logic of contemporary production relations results in their accomodation within the market economy, effectively resulting in a situation wherein the broad underclass of the socio-economically deprived subsidises costs of production.

↩ As seen in the neoliberalistion/ commodification of nature. For instance the commodification of the atmosphere in itself as a form of capital in the creation of carbon credits.

↩ Refer here for additional reading on the issue.

↩ Green Capitalism is the systematic belief that nature’s inherent value is in the monetary profit it makes. This approach is contradictory in nature since although it speaks of the “green” agenda, which implies putting a stop to depletion of Earth’s resources brought about by the “madness of economic reason”, it also advocates for capitalism, a system of accumulation which accounts for nature as a mere input to the accumulation of capital. Refer here for additional reading on the topic.

References

Budinsky, Jennifer and Susan Bryant. (2013). ““It’s Not Easy Being Green”: The Greenwashing of Environmental Discourses in Advertising.” Canadian Journal of Communication 38: 207-226.

Dolan, Paddy. (2002). “The Sustainability of “Sustainable Consumption.” Journal of Macromarketing 22 (2): 170-81.

European Commission. (2019). Going Climate-neutral By 2050: A Strategic Long-term Vision for a Prosperous, Modern, Competitive and Climate-Neutral EU Economy. Luxembourg: Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Foster, John Bellamy. (2014). “Paul Burkett’s Marx and Nature Fifteen Years After.” Monthly Review 66 (7). Accessed 28 May 2021, monthlyreview.org.

Harvey, David. (2015). Seventeen Contradictions And The End Of Capitalism. London, United Kingdom: Profile Books.

Liodakis, George. (2010). “Political Economy, Capitalism and Sustainable Development.” Sustainability 2(8): 2601-2616.

Patnaik, Utsa and Prabhat Patnaik. (2015). “Imperialism in the Era of Globalization.” Monthly Review 67(3). Accessed 29 May 2021, monthlyreview.org.

Patnaik, Prabhat. (2018). “Globalization and the Peasantry in the South.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 7(2): 234-248.

Prasad, Archana. (2020). “Ecological Crisis, Global Capital And The Reinvention Of Nature: A Perspective From The Global South.” In Rethinking The Social Sciences With Sam Moyo edited by Praveen Jha, Paris Yeros, and Walter Chambati. New York, United States of America: Columbia University Press.

Suwandi, Intan. (2019). “Labor-Value Commodity Chains: The Hidden Abode of Global Production.” Monthly Review 71 (3). Accessed 27 May 2021, monthlyreview.org

Suwandi, Intan, R. Jamil Jonna, and John Bellamy Foster. (2019). “Global Commodity Chains And The New Imperialism.” Monthly Review 70 (10). Accessed 28 May 2021, monthlyreview.org

Sweezy, Paul. M. (1967). “Rosa Luxemburg’s ‘The Accumulation of Capital’.” Science & Society 31 (4): 474-485.

United Nations. (1993). Report Of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. New York, United States of America: United Nations.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. (n.d.). “Sustainable consumption and production.” Accessed 1 June 2021, sustainabledevelopment.un.org.

Wiedmann, Thomas, Heinz Schandl, Manfred Lenzen, Daniel Moran, Sangwon Suh, James West, and Keiichiro Kanemoto. (2015). “The Material Footprint Of Nations.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (20): 6271-6276.

https://mronline.org/2021/06/09/sustain ... bal-south/

"Globalization" is a business model and does not represent the totality of political reality. The nation state ain't going nowhere, at least not 'the players' though the less robust will be recolonized by financial arrangements. Because when the going get rough and the talk seems to run out there must be a resort to force. Serious standing military force is very expensive, a cost no corporation wishes to bear. And so these costs are outsourced with the corps paying little or any and profiting mightily. Why would they give up that?

A resumption of imperialist competition, on hiatus since the end of WWII, will be the inevitable result of the decline of US hegemony. Globalization has been an economic manifestation of that hegemony, it could not happen unless the US based corporation profited thereby. The US is not interested in sharing those profits with China or anyone else. As that hegemony declines the cracks will show.

"There is great chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent."

Re: The Long Ecological Revolution

‘Net zero’ emissions is a dangerous hoax

June 10, 2021

Corporate ‘climate pledges’ mask inaction and support business as usual

by Brett Wilkins

A new report published Wednesday by a trio of progressive advocacy groups lifts the veil on so-called “net zero” climate pledges, which are often touted by corporations and governments as solutions to the climate emergency, but which the paper’s authors argue are merely a dangerous form of greenwashing that should be eschewed in favor of Real Zero policies based on meaningful, near-term commitments to reducing global greenhouse gas emissions.

The Big Con: How Big Polluters Are Advancing a ‘Net Zero’ Climate Agenda to Delay, Deceive, and Deny was published by Corporate Accountability, the Global Forest Coalition, and Friends of the Earth International, and is endorsed by over 60 environmental organizations. The paper comes ahead of this November’s United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland and amid proliferating pledges from polluting corporations and governments to achieve what they claim is carbon neutrality—increasingly via dubious offsets—by some distant date, often the year 2050.

However, the report asserts that

“Instead of offering meaningful real solutions to justly address the crisis they knowingly created and owning up to their responsibility to act beginning with drastically reducing emissions at source, polluting corporations and governments are advancing ‘net zero’ plans that require little or nothing in the way of real solutions or real effective emissions cuts. …. They see the potential for a ‘net zero’ global pathway to provide new business opportunities for them, rather than curtailing production and consumption of their polluting products.”

“After decades of inaction, corporations are suddenly racing to pledge to achieve “net zero” emissions. These include fossil fuel giants like BP, Shell, and Total; tech giants like Microsoft and Apple; retailers like Amazon and Walmart; financers like HSBC, Bank of America, and BlackRock; airlines like United and Delta; and food, livestock, and meat-producing and agriculture corporations like JBS, Nestlé, and Cargill. Polluting corporations are in a race to be the loudest and proudest to pledge ‘net zero’ emissions by 2050 or some other date in the distant future. Over recent years, more than 1,500 corporations have made ‘net zero’ commitments, an accomplishment applauded by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the U.N. Secretary-General.”

“Increasingly, the concept of ‘net zero’ is being misconstrued in political spaces as well as by individual actors to evade action and avoid responsibility,” the report states. “The idea behind big polluters’ use of ‘net zero’ is that an entity can continue to pollute as usual—or even increase its emissions—and seek to compensate for those emissions in a number of ways. Emissions are nothing more than a math equation in these plans; they can be added one place and subtracted from another place.”

“This equation is simple in theory but deeply flawed in reality,” the paper asserts. “These schemes are being used to mask inaction, foist the burden of emissions cuts and pollution avoidance on historically exploited communities, and bet our collective future through ensuring long-term, destructive impact on land and forests, oceans, and through advancing geoengineering technologies. These technologies are hugely risky, do not exist at the scale supposedly needed, and are likely to cause enormous, and likely irreversible, damage.”

Among the key findings of the report:

Big polluters, including the fossil fuel and aviation industries, lobbied heavily to ensure passage of Q45, a tax credit subsidizing carbon capture and storage. A 2020 report (pdf) from the U.S. Treasury Department’s inspector general found that fossil fuel companies improperly claimed nearly $1 billion in Q45 credits.

The International Emissions Trading Association—described by the report’s authors as “perhaps the largest global lobbyist on market and offsets, both pillars of polluters ‘net zero’ climate plans”—has leveraged its considerable power to push its greenwashing agenda at international climate talks.

Major polluters have contributed generously to universities including the Massachusetts Institute for Technology, Princeton University, Stanford University, and Imperial College London in an effort to influence “net zero”-related research. At Stanford’s Global Climate and Energy Project, ExxonMobil retained the right to formally review research before completion and was allowed to place corporate staff members on development teams.

“The best, most proven approach to justly addressing the climate crisis is to significantly reduce emissions now in an equitable manner, bringing them close to Real Zero by 2030 at the latest,” the report states, referring to a situation in which no carbon emissions are produced by a good or service without the use of offsets. “The cross-sectoral solutions we need already exist, are proven, and are scalable now… All that is missing is the political will to advance them, in spite of industry obstruction and deflection.”

“People around the globe have already made their demands clear,” the report says. “Meaningful solutions that can be implemented now are already detailed in platforms like the People’s Demands for Climate Justice, the Liability Roadmap, the Energy Manifesto, and many other resources that encompass the wisdom of those on the frontlines of the climate crisis.”

Sara Shaw, climate justice and energy program co-coordinator at Friends of the Earth International and one of the paper’s authors, said “this report shows that ‘net zero’ plans from big polluters are nothing more than a big con. The reality is that corporations like Shell have no interest in genuinely acting to solve the climate crisis by reducing their emissions from fossil fuels. They instead plan to continue business as usual while greenwashing their image with tree planting and offsetting schemes that can never ever make up for digging up and burning fossil fuels. We must wake up fast to the fact that we are falling for a trick. ‘Net zero’ risks obscuring a lack of action until it is too late.”

Lidy Nacpil, coordinator of the Asian Peoples Movement on Debt and Development—which endorsed the report—warned that “proclamations of ‘net zero’ targets are dangerous deceptions. ‘Net zero’ sounds ambitious and visionary but it actually allows big polluters and rich governments to continue emitting [greenhouse gases] which they claim will be erased through unproven and dangerous technologies, carbon trading, and offsets that shift the burden of climate action to the Global South. Big polluters and rich governments should not only reduce emissions to Real Zero, they must pay reparations for the huge climate debt owed to the Global South.”

In conclusion, the reports says world leaders must “listen to the people and once and for all prioritize people’s lives and the planet over engines of profit and destruction.”

“To avoid social and planetary collapse,” it states, “they must heed the calls of millions of people around the globe and pursue policies that justly, equitably transition our economies off of fossil fuels, and advance real solutions that prioritize life—now.”

Adapted from Common Dreams, June 9, 2021, under a Creative Commons 3.0 license.

https://climateandcapitalism.com/2021/0 ... rous-hoax/

Hate even getting near Common Dreams but this is spot on. 'Carbon Trading' is a scam. Imploring 'world leaders' to 'do something'' pathetically overestimates the power and will of those store clerks. Only the working class can act in it's own interest to turn things around, anything else is petty bourgeois fantasy and we no longer got time for that.

June 10, 2021

Corporate ‘climate pledges’ mask inaction and support business as usual

by Brett Wilkins

A new report published Wednesday by a trio of progressive advocacy groups lifts the veil on so-called “net zero” climate pledges, which are often touted by corporations and governments as solutions to the climate emergency, but which the paper’s authors argue are merely a dangerous form of greenwashing that should be eschewed in favor of Real Zero policies based on meaningful, near-term commitments to reducing global greenhouse gas emissions.

The Big Con: How Big Polluters Are Advancing a ‘Net Zero’ Climate Agenda to Delay, Deceive, and Deny was published by Corporate Accountability, the Global Forest Coalition, and Friends of the Earth International, and is endorsed by over 60 environmental organizations. The paper comes ahead of this November’s United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland and amid proliferating pledges from polluting corporations and governments to achieve what they claim is carbon neutrality—increasingly via dubious offsets—by some distant date, often the year 2050.

However, the report asserts that

“Instead of offering meaningful real solutions to justly address the crisis they knowingly created and owning up to their responsibility to act beginning with drastically reducing emissions at source, polluting corporations and governments are advancing ‘net zero’ plans that require little or nothing in the way of real solutions or real effective emissions cuts. …. They see the potential for a ‘net zero’ global pathway to provide new business opportunities for them, rather than curtailing production and consumption of their polluting products.”

“After decades of inaction, corporations are suddenly racing to pledge to achieve “net zero” emissions. These include fossil fuel giants like BP, Shell, and Total; tech giants like Microsoft and Apple; retailers like Amazon and Walmart; financers like HSBC, Bank of America, and BlackRock; airlines like United and Delta; and food, livestock, and meat-producing and agriculture corporations like JBS, Nestlé, and Cargill. Polluting corporations are in a race to be the loudest and proudest to pledge ‘net zero’ emissions by 2050 or some other date in the distant future. Over recent years, more than 1,500 corporations have made ‘net zero’ commitments, an accomplishment applauded by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the U.N. Secretary-General.”

“Increasingly, the concept of ‘net zero’ is being misconstrued in political spaces as well as by individual actors to evade action and avoid responsibility,” the report states. “The idea behind big polluters’ use of ‘net zero’ is that an entity can continue to pollute as usual—or even increase its emissions—and seek to compensate for those emissions in a number of ways. Emissions are nothing more than a math equation in these plans; they can be added one place and subtracted from another place.”

“This equation is simple in theory but deeply flawed in reality,” the paper asserts. “These schemes are being used to mask inaction, foist the burden of emissions cuts and pollution avoidance on historically exploited communities, and bet our collective future through ensuring long-term, destructive impact on land and forests, oceans, and through advancing geoengineering technologies. These technologies are hugely risky, do not exist at the scale supposedly needed, and are likely to cause enormous, and likely irreversible, damage.”

Among the key findings of the report:

Big polluters, including the fossil fuel and aviation industries, lobbied heavily to ensure passage of Q45, a tax credit subsidizing carbon capture and storage. A 2020 report (pdf) from the U.S. Treasury Department’s inspector general found that fossil fuel companies improperly claimed nearly $1 billion in Q45 credits.

The International Emissions Trading Association—described by the report’s authors as “perhaps the largest global lobbyist on market and offsets, both pillars of polluters ‘net zero’ climate plans”—has leveraged its considerable power to push its greenwashing agenda at international climate talks.

Major polluters have contributed generously to universities including the Massachusetts Institute for Technology, Princeton University, Stanford University, and Imperial College London in an effort to influence “net zero”-related research. At Stanford’s Global Climate and Energy Project, ExxonMobil retained the right to formally review research before completion and was allowed to place corporate staff members on development teams.

“The best, most proven approach to justly addressing the climate crisis is to significantly reduce emissions now in an equitable manner, bringing them close to Real Zero by 2030 at the latest,” the report states, referring to a situation in which no carbon emissions are produced by a good or service without the use of offsets. “The cross-sectoral solutions we need already exist, are proven, and are scalable now… All that is missing is the political will to advance them, in spite of industry obstruction and deflection.”

“People around the globe have already made their demands clear,” the report says. “Meaningful solutions that can be implemented now are already detailed in platforms like the People’s Demands for Climate Justice, the Liability Roadmap, the Energy Manifesto, and many other resources that encompass the wisdom of those on the frontlines of the climate crisis.”

Sara Shaw, climate justice and energy program co-coordinator at Friends of the Earth International and one of the paper’s authors, said “this report shows that ‘net zero’ plans from big polluters are nothing more than a big con. The reality is that corporations like Shell have no interest in genuinely acting to solve the climate crisis by reducing their emissions from fossil fuels. They instead plan to continue business as usual while greenwashing their image with tree planting and offsetting schemes that can never ever make up for digging up and burning fossil fuels. We must wake up fast to the fact that we are falling for a trick. ‘Net zero’ risks obscuring a lack of action until it is too late.”

Lidy Nacpil, coordinator of the Asian Peoples Movement on Debt and Development—which endorsed the report—warned that “proclamations of ‘net zero’ targets are dangerous deceptions. ‘Net zero’ sounds ambitious and visionary but it actually allows big polluters and rich governments to continue emitting [greenhouse gases] which they claim will be erased through unproven and dangerous technologies, carbon trading, and offsets that shift the burden of climate action to the Global South. Big polluters and rich governments should not only reduce emissions to Real Zero, they must pay reparations for the huge climate debt owed to the Global South.”

In conclusion, the reports says world leaders must “listen to the people and once and for all prioritize people’s lives and the planet over engines of profit and destruction.”

“To avoid social and planetary collapse,” it states, “they must heed the calls of millions of people around the globe and pursue policies that justly, equitably transition our economies off of fossil fuels, and advance real solutions that prioritize life—now.”

Adapted from Common Dreams, June 9, 2021, under a Creative Commons 3.0 license.

https://climateandcapitalism.com/2021/0 ... rous-hoax/

Hate even getting near Common Dreams but this is spot on. 'Carbon Trading' is a scam. Imploring 'world leaders' to 'do something'' pathetically overestimates the power and will of those store clerks. Only the working class can act in it's own interest to turn things around, anything else is petty bourgeois fantasy and we no longer got time for that.

"There is great chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent."

Re: The Long Ecological Revolution

CAPITAL VS NATURE AND HUMANITY

The Double Deformation

June 17, 2021

Economic exploitation is only one aspect of capitalism. The crisis of humanity and the crisis of the earth system are inseparable

Michael A. Lebowitz is professor emeritus of economics at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada. His books include The Socialist Imperative, The Contradictions of Real Socialism, and Between Capitalism and Community, all published by Monthly Review Press. This article is excerpted, with permission, from “Know Your Enemy: How to Defeat Capitalism,” published this month in LINKS: International Journal of Socialist Renewal.

by Michael A. Lebowitz

The exploitation of workers is at the core of capitalism. It explains capital’s drive to divide workers in order to grow. Exploitation is the source of the inequality characteristic of capitalism. To fight inequality, we must fight capitalist exploitation. However, inequality is only one aspect of capitalism. In and by itself, exploitation is inadequate to grasp the effects of capital’s drive and thus the products of capitalism. Focus upon exploitation is one-sided because you do not know the enemy unless you understand the double deformation inherent in capitalism.

Recall that human beings and Nature are the ultimate inputs into production. In capitalist production, they serve specifically as means for the purpose of the growth of capital. The result is deformation — capitalistically-transformed Nature and capitalistically-transformed human beings. Capitalist production, Marx stressed, “only develops the technique and the degree of combination of the social process of production by simultaneously undermining the original sources of all wealth — the soil and the worker.”

But why?

The Deformation of Nature

By itself, Nature is characterized by a metabolic process through which it converts various inputs and transforms these into the basis for its reproduction. In his discussion of the production of wheat, for example, Marx identified a “vegetative or physiological process” involving the seeds and “various chemical ingredients supplied by the manure, salts contained in the soil, water, air, light.”

Through this process, inorganic components are “assimilated by the organic components and transformed into organic material.” Their form is changed in this metabolic process, from inorganic to organic through what Marx called “the expenditure of nature.” Also part of the “universal metabolism of nature” is the further transformation of organic components, their deterioration and dying through their “consumption by elemental forces.”

In this way, the conditions for rebirth (for example, the “vitality of the soil”) are themselves products of this metabolic process. “The seed becomes the unfolded plant, the blossom fades, and so forth.” Birth, death, renewal are moments characteristic of the “metabolism prescribed by the natural laws of life itself.”

This universal metabolism of Nature, however, must be distinguished from the relation in which a human being “mediates, regulates and controls the metabolism between himself and nature.” That labor process involves the “appropriation of what exists in nature for the requirements of man. It is the universal condition for the metabolic interaction between man and nature.” This “ever-lasting nature-imposed condition of human existence,” Marx pointed out, is “common to all forms of society in which human beings live.”

As we have indicated, however, under capitalist relations of production, the preconceived goal of production is the growth of capital. The particular metabolic process that occurs in this case is one in which human labor and Nature are converted into surplus value, the basis for that growth.

Accordingly, rather than a process that begins with “man and his labour on one side, nature and its materials on the other,” in capitalist relations the starting point is capital, and “the labour process is a process between things the capitalist has purchased, things which belong to him.” It is “appropriation of what exists in nature for the requirements” not of man but of capital.

There is, as noted, “exploration of the earth in all directions” for a single purpose— to find new sources of raw materials to ensure the generation of profits. Nature, “the universal material for labour,” the “original larder” for human existence, is here a means not for human existence but for capital’s existence.

As we have seen, while capital’s tendency to grow by leaps and bounds comes up against a barrier insofar as plant and animal products are “subject to certain organic laws involving naturally determined periods of time”, capital constantly drives beyond each barrier it faces.

However, there is a barrier it does not escape. Marx noted, for example, that “the entire spirit of capitalist production, which is oriented towards the most immediate monetary profit — stands in contradiction to agriculture, which has to concern itself with the whole gamut of permanent conditions of life required by the chain of human generations.” Indeed, the very nature of production under capitalist relations violates “the metabolic interaction between man and the earth,” it produces “an irreparable rift in the interdependent process of social metabolism, a metabolism prescribed by the natural laws of life itself.”

That “irreparable” metabolic rift that Marx described is neither a short-term disturbance nor unique to agriculture. The “squandering of the vitality of the soil” is a paradigm for the way in which the “metabolism prescribed by the natural laws of life itself” is violated under capitalist relations of production.

In fact, there is nothing inherent in agricultural production that leads to that “squandering of the vitality of the soil.” On the contrary, Marx pointed out that a society can bequeath the earth “in an improved state to succeeding generations.” But this requires an understanding that “agriculture forms a mode of production sui generis, because the organic process is involved, in addition to the mechanical and chemical process, and the natural reproduction process is merely controlled and guided.” The same is true, too, in the case of fishing, hunting, and forestry. Maintenance and improvement of the vitality of the soil and of other sectors dependent upon organic conditions requires the recognition of the necessity for “systematic restoration as a regulative law of social production.”

With every increase in capitalist production, there are growing demands upon the natural environment, and the tendency to exhaust Nature’s larder and to generate unabsorbed and unutilizable waste is not at all limited to the metabolic rift that Marx described with respect to capitalist agriculture.

Thus, Marx indicated that “extractive industry (mining is the most important) is likewise an industry sui generis, because no reproduction process whatever takes place in it, at least not one under our control or known to us,” and, he noted as well “the exhaustion of forests, coal and iron mines, and so on.” Given its preoccupation with its need to grow, capital has no interest in the contradiction between its logic and the “natural laws of life itself.” The contradiction between its drive for infinite growth and a finite, limited earth is not a concern because for capital there is always another source of growth to be found.

Like a vampire, it seeks the last possible drop of blood and does not worry about keeping its host alive.

Accordingly, since capital does not worry about “simultaneously undermining the original sources of all wealth — the soil and the worker,” sooner or later it destroys both. Marx’s comment with respect to capital’s drive to drain every ounce of energy from the worker describes capital’s relation to the natural world precisely:

“Après moi le deluge! is the watchword of every capitalist and every capitalist nation. Capital therefore takes no account of the health and the length of life of the worker, unless society forces it to do so.”

We are seeing the signs of that approaching deluge. Devastating wildfires, droughts, powerful hurricanes, warming oceans, floods, rising sea levels, pollution, pandemics, disappearing species, etc., are becoming commonplace — but there is nothing in capital’s metabolic process that would check that. If, for example, certain materials become scarce and costly, capital will not scale back and accept less or no growth; rather, it will scour the earth to search for new sources and substitutes.

Can society prevent the crisis of the earth system, the deluge? Not currently. The ultimate deformation of Nature is the prospect because the second deformation makes it easier to envision the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

The Deformation of Human Beings

Human beings are not static and fixed. Rather, they are a work in process because they develop as the result of their activity. They change themselves as they act in and upon the world. In this respect there are always two products of human activity — the change in circumstances and the change in the human being. In the very act of producing, Marx commented, “the producers change, too, in that they bring out new qualities in themselves, develop themselves in production, transform themselves, develop new powers and new ideas, new modes of intercourse, new needs and new language.”

In the process of producing, the worker “acts upon external nature and changes it, and in this way he simultaneously changes his own nature.”

In this “self-creation of man as a process,” the character of that human product flows from the nature of that productive activity. Under particular circumstances, that process can be one in which people are able to develop their capacities in an all-rounded way.

As Marx put it, “when the worker co-operates in a planned way with others, he strips off the fetters of his individuality, and develops the capabilities of his species”. In such a situation, associated producers may expend “their many different forms of labour-power in full self-awareness as one single social labour force”, and the means of production are “there to satisfy the worker’s own need for development.”

For example, if workers democratically decide upon a plan, work together to achieve its realization, solve problems which emerge and shift in this process from activity to activity, they engage in a constant succession of acts which expand their capacities. For workers in this situation, there is the “absolute working-out of his creative potentialities,” the “complete working out of the human content,” the “development of all human powers as such the end in itself.”

Collective activity under these relations produces “free individuality, based on the universal development of individuals and on their subordination of their communal, social productivity as their social wealth.” In the society of the future, Marx concluded, the productive forces of people will have “increased with the all-round development of the individual, and all the springs of co-operative wealth flow more abundantly”.

But that’s not the character of activity under capitalist relations of production, where “it is not the worker who employs the conditions of his work, but rather the reverse, the conditions of work employ the worker.” While we know how central exploitation is from the perspective of capital, consider the effects upon workers of what capital does to ensure that exploitation. We’ve seen how capital constantly attempts to separate workers and, indeed, fosters antagonism among them (the “secret” of its success); how capital introduces changes in production that divides them further, intensifies the production process and expands the reserve army that fosters competition.

What’s the effect? Marx pointed out that “all means for the development of production” under capitalism “distort the worker into ah fragment of a man,” degrade him and “alienate him from the intellectual potentialities of the labour process”. In Capital, he described the mutilation, the impoverishment, the “crippling of body and mind” of the worker “bound hand and foot for life to a single specialized operation” that occurs in the division of labor characteristic of the capitalist process of manufacturing.

But did the subsequent development of machinery end that crippling of workers? Marx’s response was that under capitalist relations such developments complete the “separation of the intellectual faculties of the production process from manual labour.” Thinking and doing become separate and hostile, and “every atom of freedom, both in bodily and in intellectual activity” is lost.

In short, a particular type of person is produced in capitalism. Producing within capitalist relations is what Marx called a process of a “complete emptying-out,” “total alienation,” the “sacrifice of the human end-in-itself to an entirely external end”. Indeed, the worker is so alienated that, though working with others, he “actually treats the social character of his work, its combination with the work of others for a common goal, as a power that is alien to him.”

In this situation, in order to fill the vacuum of our lives, we need things — we are driven to consume. In addition to producing commodities and capital itself, thus, capitalism produces a fragmented, crippled human being, whose enjoyment consists in possessing and consuming things. More and more things. Capital constantly generates new needs for workers, and it is upon this, Marx noted, that “the contemporary power of capital rests.”

In short, every new need for capitalist commodities is a new link in the golden chain that links workers to capital.

Accordingly, rather than producing a working class that wants to put an end to capitalism, capital tends to produce the working class it needs, workers who treat capitalism as common sense. As Marx concluded:

“The advance of capitalist production develops a working class which by education, tradition and habit looks upon the requirements of that mode of production as self-evident natural laws. The organization of the capitalist process of production, once it is fully developed, breaks down all resistance.”

To this, he added that capital’s generation of a reserve army of the unemployed “sets the seal on the domination of the capitalist over the worker.” That constant generation of a relative surplus population of workers means, Marx argued, that wages are “confined within limits satisfactory to capitalist exploitation, and lastly, the social dependence of the worker on the capitalist, which is indispensable, is secured.”

Accordingly, Marx concluded that the capitalist can rely upon the worker’s “dependence on capital, which springs from the conditions of production themselves, and is guaranteed in perpetuity by them.”

However, while it is possible that workers may remain socially dependent upon capital in perpetuity, that doesn’t mean that capital’s incessant growth can continue in perpetuity. In fact, given that workers deformed by capital accept capital’s requirement to grow “as self-evident natural laws,” their deformation supports the deformation of Nature.

In turn, the increase in flooding, drought and other extreme climate changes and resulting mass migrations which are the product of the deformation of Nature intensify divisions and antagonism among workers. The crisis of the earth system and the crisis of humanity are one.

https://climateandcapitalism.com/2021/0 ... formation/

"There is great chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent."

Re: The Long Ecological Revolution

Interacting climate tipping points may fall like dominoes

June 26, 2021

Cascading changes could move Earth into a dangerous state for the future of humanity and nature

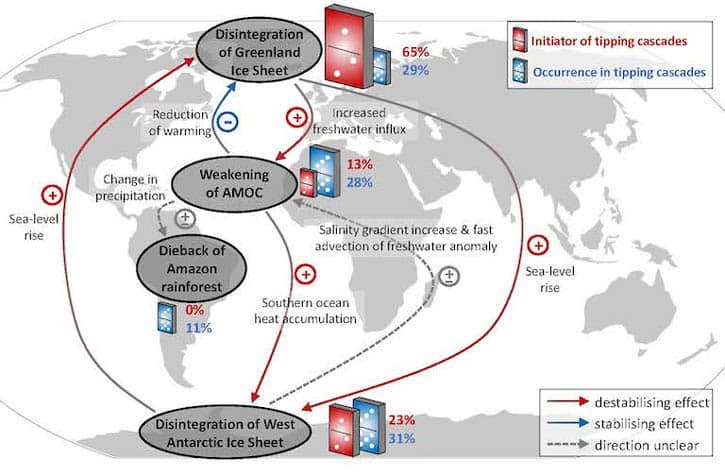

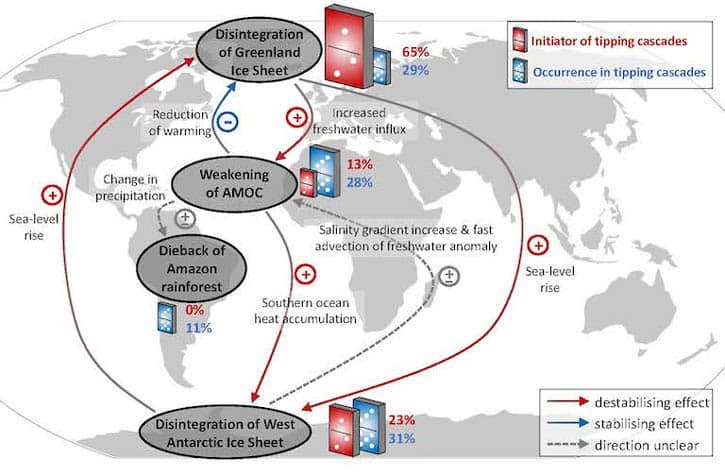

Interactions between climate tipping elements and their roles in tipping cascades.

by Elizabeth Claire Alberts

Mongobay, June 23, 2021

A new risk analysis has found that the tipping points of five of Earth’s subsystems — the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, the Greenland Ice Sheet, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Amazon rainforest — could interact with each other in a destabilizing manner.

It suggests that these changes could occur even before temperatures reach 2°C (3.6°F) above pre-industrial levels, which is the upper limit of the Paris Agreement.

The interactions between the different tipping elements could also lower critical temperature thresholds, essentially allowing tipping cascades to occur earlier than expected, according to the research.

Experts not involved in the study say the findings are a significant contribution to the field, but do not adequately address the timescales over which these changes could occur.

When the first tile in a line of dominoes tips forward, it affects everything in front of it. One after another, lined-up dominoes knock into each other and topple. This is essentially what could happen to ice sheets, ocean currents and even the Amazon biome if critical tipping points are crossed, according to a new risk analysis. The destabilization of one element could impact the others, creating a domino effect of drastic changes that could move the Earth into an unfamiliar state — one potentially dangerous to the future of humanity and nature as we know it.

The study, published this month in Earth System Dynamics, examines the interactions between five subsystems that are known to have vital thresholds, or tipping points, that could trigger irreversible changes. They include the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, the Greenland Ice Sheet, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Amazon Rainforest.

Scientists believe the AMOC could reach its critical threshold when warming temperatures weaken the current enough to substantially slow it, halt it, or redirect it, which could plunge parts of the northern hemisphere into a period of record cold, even as global warming continues elsewhere. Likewise, the Antarctic ice sheet may reach its irreversible threshold when warming temperatures trigger a state of constant ice loss, which could ultimately result in a 4-meter (13-foot) rise in global sea levels over the coming centuries. In fact, it’s suggested that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet may have already passed its critical threshold, and that ice loss is unstoppable now.

These individual tipping points are largely being driven by human-caused climate change, which is considered to be one of nine planetary boundaries — scientifically identified limits on change to vital Earth systems that currently regulate and sustain life. Overshooting those boundaries could lead to new natural paradigms catastrophic for humanity. Climate change has its own threshold of 350 parts per million (ppm) of CO2, which is the amount that scientists say the atmosphere can safely hold, but this threshold was already passed in 1988. In 2021, CO2 exceeded 417 ppm, which is 50% higher than pre-industrial levels.

To conduct this new study, the research team used a conceptual modeling process to analyze the interactions between these five Earth subsystems. What they found was that more than a third of these elements showed “tipping cascades” even before temperatures reached 2° Celsius (3.6° Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, which is the upper limit of the 2015 Paris climate agreement. At present, almost no nation on Earth is on target to meet its Paris carbon reduction goals.

Significantly, the study also found that the interactions between the tipping elements could lower critical temperature thresholds, essentially allowing tipping cascades to occur earlier than anticipated. Additionally, the researchers found that the Greenland Ice Sheet would function as an initiator of tipping cascades, while the AMOC would act as a transmitter that would push further changes, including dieback of the Amazon. Most of these tipping elements have been projected to have a destabilizing effect on each other, with the exception of the weakening of the AMOC, which could actually make the North Atlantic region colder and help stabilize the Greenland Ice Sheet.

“We found that the overall interactions tend to make [things] worse, so to say, and tend to be destabilizing,” lead author Nico Wunderling, a scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, told Mongabay.

He said that the findings suggest that we already face significant risk, but that the study does not necessarily provide a forecast. “We have made a risk analysis,” Wunderling said. “This is not a prediction, but it’s more like, ‘OK, if we have this warming, then we might face an increasing risk of tipping cascades.’”

Tim Lenton, a professor of climate change and Earth system science at the University of Exeter, U.K., and co-author of a similar study on tipping points, says the new paper is a “useful addition to the assessment of climate tipping point interactions.”

“The important takeaway message from this study is that the cascading causal interactions between four different climate tipping elements lower the ‘safe’ temperature level at which the risk of triggering tipping points is minimized,” Lenton told Mongabay in an email. “In fact the study suggests that below 2°C of global warming (above pre-industrial) — i.e. in the Paris agreement target range — there could still be a significant risk of triggering cascading climate tipping points.”

However, Lenton says the study does not unpack the timescale in which these tipping cascades would occur, focusing more on their consequences. “In the case of ice sheet collapse this can take many centuries,” he said. “Hence the results should be viewed as ‘commitments’ to potentially irreversible changes and cascades that we may be making soon, but will leave as a grim legacy to future generations to feel their full impact.”

Juan Rocha, an ecologist at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, says the findings of the study affirm previous hypotheses about how “the tipping of one system can affect the likelihood of others in a self-amplifying way,” although he also notes its oversight of evaluating timescales.

“The Amazon is likely to tip way earlier than AMOC or Greenland,” Rocha told Mongabay. “Future work needs to take into account the diversity and uncertainty of the feedbacks at play for each tipping element to really understand how likely [it] is that one system can tip the other.”

Rocha says he’s pleased the authors undertook this study and hopes others continue to build on this research.

“I would like to extend an invitation to the authors and the scientific community to keep working on these important questions,” he said. “There is a lot of work to do, a lot that we do not know, and our models can only get us so far. Understanding how different systems of the Earth … are connected is fundamental to avoid the risk of domino effects, but also to empower people to act on time, identify leverage points and understand the extent of action or lack of it.”

Italics added. The problem with this and other studies is that too many, for reasons of predilection or ideology, will conflate studies of this nature as prediction, thereby succumbing to and encouraging despair, which is the last damn thing we need. Like it or not we are living in the Anthropocene, a sorry state of affairs to be sure, which can only be addressed by serious intent and human action. Yes, it could be 'too late'(however you measure that, opinions vary...) but we won't really know until it hammers us into the ground, and maybe not even then. But in the meantime instead of chucking it all or engaging in primitivist fantasies we got work to do . Without doubt the first and most important step is to rid ourselves of the destructive and wasteful capitalist mode of production.

June 26, 2021

Cascading changes could move Earth into a dangerous state for the future of humanity and nature

Interactions between climate tipping elements and their roles in tipping cascades.

by Elizabeth Claire Alberts

Mongobay, June 23, 2021

A new risk analysis has found that the tipping points of five of Earth’s subsystems — the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, the Greenland Ice Sheet, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Amazon rainforest — could interact with each other in a destabilizing manner.

It suggests that these changes could occur even before temperatures reach 2°C (3.6°F) above pre-industrial levels, which is the upper limit of the Paris Agreement.

The interactions between the different tipping elements could also lower critical temperature thresholds, essentially allowing tipping cascades to occur earlier than expected, according to the research.

Experts not involved in the study say the findings are a significant contribution to the field, but do not adequately address the timescales over which these changes could occur.

When the first tile in a line of dominoes tips forward, it affects everything in front of it. One after another, lined-up dominoes knock into each other and topple. This is essentially what could happen to ice sheets, ocean currents and even the Amazon biome if critical tipping points are crossed, according to a new risk analysis. The destabilization of one element could impact the others, creating a domino effect of drastic changes that could move the Earth into an unfamiliar state — one potentially dangerous to the future of humanity and nature as we know it.

The study, published this month in Earth System Dynamics, examines the interactions between five subsystems that are known to have vital thresholds, or tipping points, that could trigger irreversible changes. They include the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, the Greenland Ice Sheet, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Amazon Rainforest.

Scientists believe the AMOC could reach its critical threshold when warming temperatures weaken the current enough to substantially slow it, halt it, or redirect it, which could plunge parts of the northern hemisphere into a period of record cold, even as global warming continues elsewhere. Likewise, the Antarctic ice sheet may reach its irreversible threshold when warming temperatures trigger a state of constant ice loss, which could ultimately result in a 4-meter (13-foot) rise in global sea levels over the coming centuries. In fact, it’s suggested that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet may have already passed its critical threshold, and that ice loss is unstoppable now.

These individual tipping points are largely being driven by human-caused climate change, which is considered to be one of nine planetary boundaries — scientifically identified limits on change to vital Earth systems that currently regulate and sustain life. Overshooting those boundaries could lead to new natural paradigms catastrophic for humanity. Climate change has its own threshold of 350 parts per million (ppm) of CO2, which is the amount that scientists say the atmosphere can safely hold, but this threshold was already passed in 1988. In 2021, CO2 exceeded 417 ppm, which is 50% higher than pre-industrial levels.

To conduct this new study, the research team used a conceptual modeling process to analyze the interactions between these five Earth subsystems. What they found was that more than a third of these elements showed “tipping cascades” even before temperatures reached 2° Celsius (3.6° Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, which is the upper limit of the 2015 Paris climate agreement. At present, almost no nation on Earth is on target to meet its Paris carbon reduction goals.

Significantly, the study also found that the interactions between the tipping elements could lower critical temperature thresholds, essentially allowing tipping cascades to occur earlier than anticipated. Additionally, the researchers found that the Greenland Ice Sheet would function as an initiator of tipping cascades, while the AMOC would act as a transmitter that would push further changes, including dieback of the Amazon. Most of these tipping elements have been projected to have a destabilizing effect on each other, with the exception of the weakening of the AMOC, which could actually make the North Atlantic region colder and help stabilize the Greenland Ice Sheet.

“We found that the overall interactions tend to make [things] worse, so to say, and tend to be destabilizing,” lead author Nico Wunderling, a scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, told Mongabay.

He said that the findings suggest that we already face significant risk, but that the study does not necessarily provide a forecast. “We have made a risk analysis,” Wunderling said. “This is not a prediction, but it’s more like, ‘OK, if we have this warming, then we might face an increasing risk of tipping cascades.’”

Tim Lenton, a professor of climate change and Earth system science at the University of Exeter, U.K., and co-author of a similar study on tipping points, says the new paper is a “useful addition to the assessment of climate tipping point interactions.”

“The important takeaway message from this study is that the cascading causal interactions between four different climate tipping elements lower the ‘safe’ temperature level at which the risk of triggering tipping points is minimized,” Lenton told Mongabay in an email. “In fact the study suggests that below 2°C of global warming (above pre-industrial) — i.e. in the Paris agreement target range — there could still be a significant risk of triggering cascading climate tipping points.”

However, Lenton says the study does not unpack the timescale in which these tipping cascades would occur, focusing more on their consequences. “In the case of ice sheet collapse this can take many centuries,” he said. “Hence the results should be viewed as ‘commitments’ to potentially irreversible changes and cascades that we may be making soon, but will leave as a grim legacy to future generations to feel their full impact.”

Juan Rocha, an ecologist at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, says the findings of the study affirm previous hypotheses about how “the tipping of one system can affect the likelihood of others in a self-amplifying way,” although he also notes its oversight of evaluating timescales.

“The Amazon is likely to tip way earlier than AMOC or Greenland,” Rocha told Mongabay. “Future work needs to take into account the diversity and uncertainty of the feedbacks at play for each tipping element to really understand how likely [it] is that one system can tip the other.”

Rocha says he’s pleased the authors undertook this study and hopes others continue to build on this research.

“I would like to extend an invitation to the authors and the scientific community to keep working on these important questions,” he said. “There is a lot of work to do, a lot that we do not know, and our models can only get us so far. Understanding how different systems of the Earth … are connected is fundamental to avoid the risk of domino effects, but also to empower people to act on time, identify leverage points and understand the extent of action or lack of it.”

https://climateandcapitalism.com/2021/0 ... -dominoes/ABSTRACT

Interacting tipping elements increase risk of climate domino effects under global warming.

With progressing global warming, there is an increased risk that one or several tipping elements in the climate system might cross a critical threshold, resulting in severe consequences for the global climate, ecosystems and human societies. While the underlying processes are fairly well-understood, it is unclear how their interactions might impact the overall stability of the Earth’s climate system.

As of yet, this cannot be fully analyzed with state-of-the-art Earth system models due to computational constraints as well as some missing and uncertain process representations of certain tipping elements. Here, we explicitly study the effects of known physical interactions among the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) and the Amazon rainforest using a conceptual network approach.

We analyze the risk of domino effects being triggered by each of the individual tipping elements under global warming in equilibrium experiments. In these experiments, we propagate the uncertainties in critical temperature thresholds, interaction strengths and interaction structure via large ensembles of simulations in a Monte Carlo approach.

Overall, we find that the interactions tend to destabilize the network of tipping elements. Furthermore, our analysis reveals the qualitative role of each of the four tipping elements within the network, showing that the polar ice sheets on Greenland and West Antarctica are oftentimes the initiators of tipping cascades, while the AMOC acts as a mediator transmitting cascades.

This indicates that the ice sheets, which are already at risk of transgressing their temperature thresholds within the Paris range of 1.5 to 2 ∘C, are of particular importance for the stability of the climate system as a whole.

Wunderling, N., Donges, J. F., Kurths, J., and Winkelmann, R., “Interacting tipping elements increase risk of climate domino effects under global warming,” Earth System Dynamics 12, 601–619.

Italics added. The problem with this and other studies is that too many, for reasons of predilection or ideology, will conflate studies of this nature as prediction, thereby succumbing to and encouraging despair, which is the last damn thing we need. Like it or not we are living in the Anthropocene, a sorry state of affairs to be sure, which can only be addressed by serious intent and human action. Yes, it could be 'too late'(however you measure that, opinions vary...) but we won't really know until it hammers us into the ground, and maybe not even then. But in the meantime instead of chucking it all or engaging in primitivist fantasies we got work to do . Without doubt the first and most important step is to rid ourselves of the destructive and wasteful capitalist mode of production.

"There is great chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent."

Re: The Long Ecological Revolution

A People’s Green New Deal: An interview with Max Ajl

Les Mées, 2016, by Andreas Gursky

Climate crisis is a disaster which impacts us all, but the culpability is not evenly distributed. The rich nations of North America, Europe, Japan and Australia have contributed 60% of global cumulative CO2 emissions, compared to 13% for the two largest developing economies, China and India, taken together. And yet the overwhelming cost of global warming is being borne by the oppressed world, where ecosystem collapse is causing mass population displacements, while those countries most responsible move further towards fortress nationalisms. It is inevitable that this situation would engender a geographic rift in the environmental movement itself, an issue which is foregrounded in Max Ajl’s new book, A People’s Green New Deal, published by Pluto Press.

In this interview for Ebb Magazine, Ajl offers his perspective on the issues of ecologically unequal exchange, the Palestinian national liberation struggle, China’s model of agrarian revolution, Andreas Malm’s ‘ecological Leninism’, and the prospects for North-South convergence around environmental justice.

Alfie Hancox: The last few years have seen no shortage of left-wing commentary on Green New Deal policies and green manifestos. However, in A People’s Green New Deal, you take a different approach, drawing on Marxist dependency theorists like Samir Amin to foreground capitalist uneven development and what you call ‘ecologically unequal exchange’. Why is this perspective important for progressive environmentalism, and what does it tell us about the limits of social democratic Green New Deals?

Max Ajl: Ecologically uneven exchange (EUE), or essentially the North using a disproportionate share of world resources and space for waste, including more recently atmospheric space for carbon dioxide, has been a structural feature of historical capitalism. EUE is essentially an elaboration of earlier insights from Third World dependency theory, like the work of Samir Amin or Ruy Mauro Marini. It teaches us that southern labouring people are not only more oppressed and exploited, but they also encounter more social and ecological ravages than people in the North. Furthermore, these theories help us interpret modern political and economic history. By showing us how uneven exchange and primitive accumulation happen, they can show us what mechanisms are necessary to challenge them: Third World sovereignty, commodity cartels, national states untrammelled by US/Israeli warfare and subversion, collective self-reliance and bargaining at the United Nations, agrarian reform and sovereign industrialisation, appropriate technologies and eyes askance at unasked-for ‘technology transfer,’ internal and external price engineering. Indeed, many of these ideas were the planks of historical manifestos like the call for a New International Economic Order. We are also learning to see how inter-national oppression and ecological destruction register unevenly within peripheral countries.