Reflections on the crisis of the political subject in a warming planet

Originally published: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung on March 27, 2024 by Camila Barragán (more by Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung) | (Posted Mar 30, 2024)

Summer 2023 saw record-breaking temperatures, affirming the alarming trend of global warming, which even sophisticated climate models underestimated. At the same time, Latin American communities mobilized against extractivism and for environmental protection, exemplified by the #SíalYasuní campaign in Ecuador, successfully advocating to keep oil in the ground to combat climate change and protect Indigenous groups and biodiversity. Similarly, in Argentina’s Jujuy province, an uprising opposed a constitutional reform threatening Indigenous communities’ rights due to lithium extraction. These events underscore different aspects of the contemporary socio-ecological crisis. The author aims to contribute to discussions on radical socio-ecological change, by presenting a reflection on analytical tools from the tradition of Frankfurt School critical theory, including some contemporary formulations.

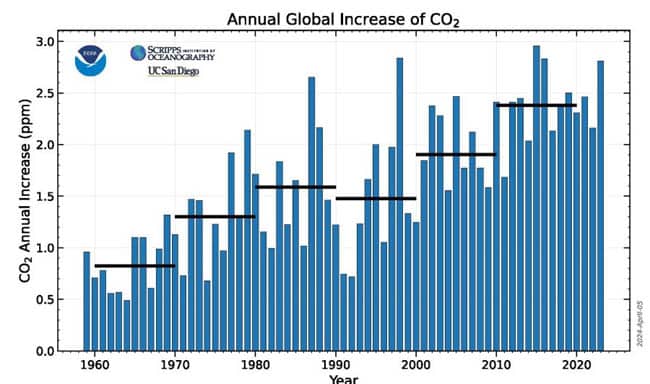

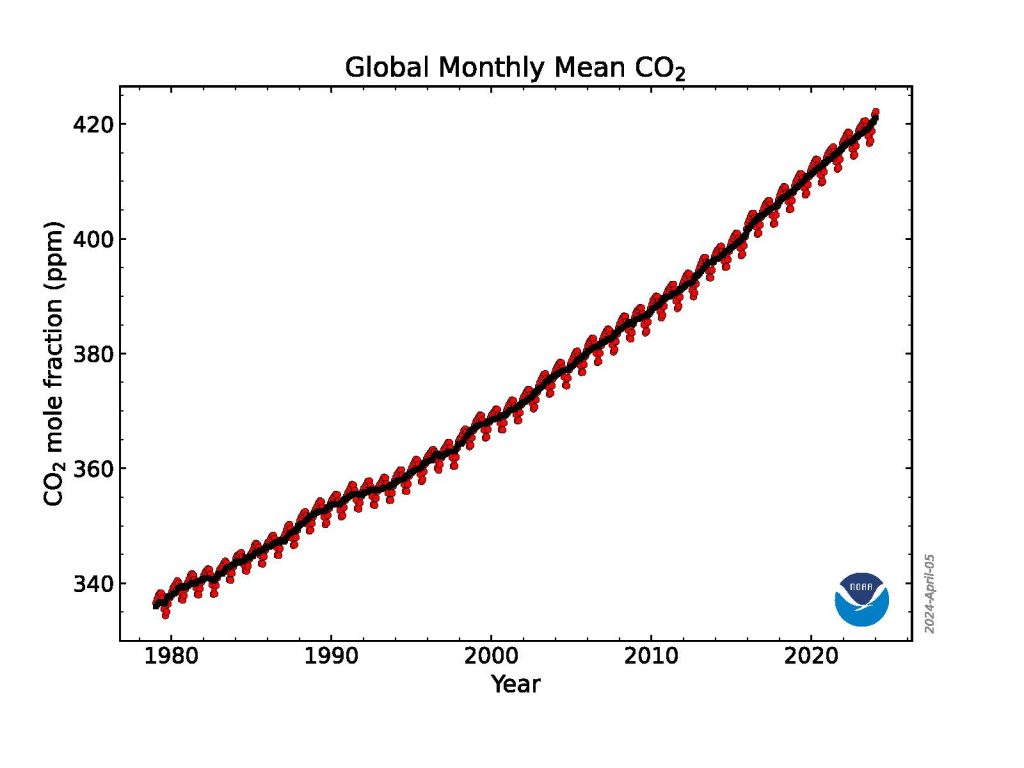

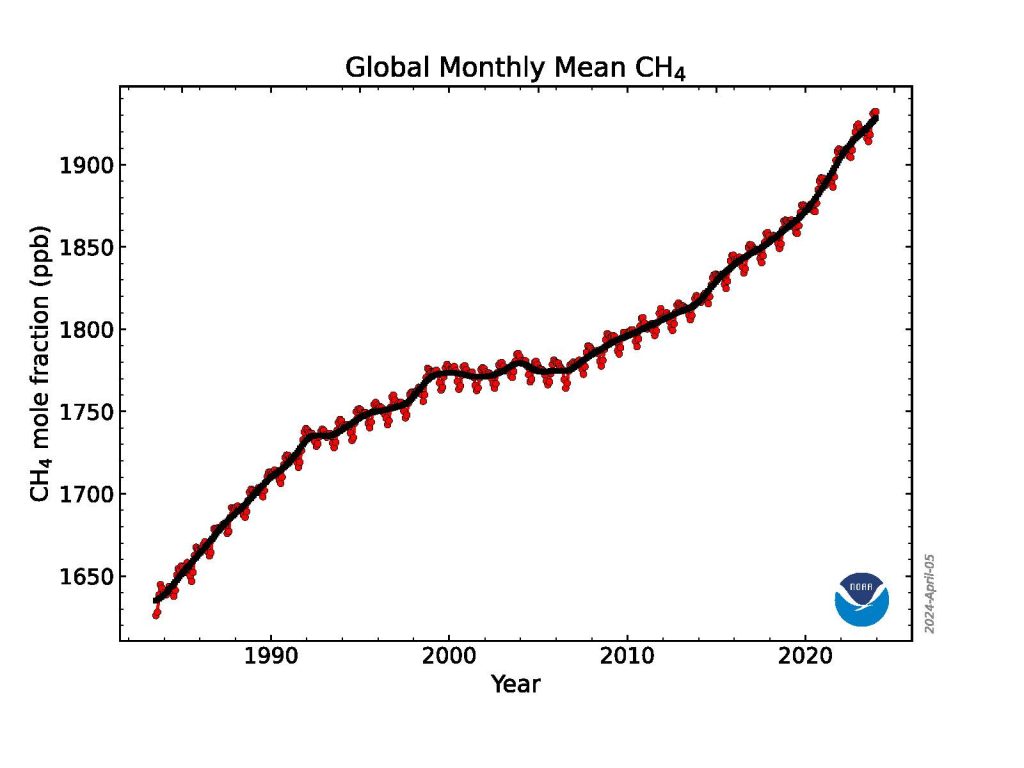

It’s official: summer 2023 (in the Northern Hemisphere) was by far the warmest summer ever recorded (Planelles and Silva 2023). This is not a coincidence, but the confirmation of a global warming trend whose pace seems to have been underestimated even by the sophisticated climate models from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Just as unprecedented peak temperatures were being recorded in several cities around the world, organized communities in Latin America were mobilizing against extractivism, as well as in favour of environmental protection and the right to protest in its defence. One of these was the #SíalYasuní (Yes to Yasuní) campaign in Ecuador, part of a struggle to stop oil exploration and drilling in the Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (ITT) oil block located within the Yasuní National Park (Rosero 2023a; YASunidos n.d.). As stated by the campaigners, avoiding oil drilling is the only sensible solution to stop climate change, to protect the Indigenous groups living in the region, and to preserve biodiversity. The campaign concluded with a referendum held on 20 August 2023, in which the majority of Ecuador’s population voted in favour of keeping the oil in the ground, forcing the dismantling of oil operations in the region within a year (Rosero 2023b). A great success, the result of this referendum must be placed in a longer-term context: ten years have gone by since the environmental organizations behind the campaign started mobilizing for the definitive halt of oil exploitation in Yasuní. Around the same time, almost 3,000 km southeast of Yasuní, in the province of Jujuy, Argentina, a popular uprising was taking place involving Indigenous communities, trade unions, and social organizations (Svampa 2023). The core of the uprising was the opposition to a provincial constitutional reform. The amendments would entail a violation of the right to protest for the communities of Jujuy, who already face the threat of dispossession of their lands. The main threat comes from lithium extraction, a key mineral for an “energy transition” whose urgent and massive implementation is presented as the only possible alternative to the fossil fuel system. This reform further undermines the communities’ capacity to resist the extractivist attack on their lands.

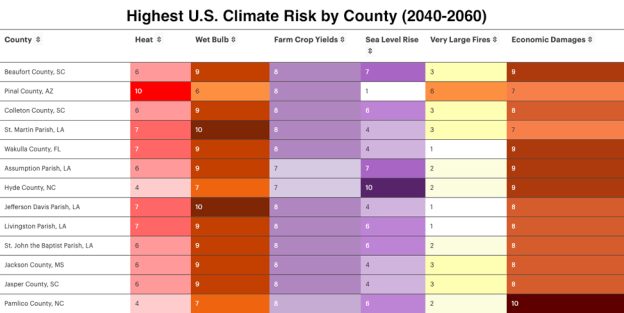

These episodes reveal different dimensions of the contemporary socio-ecological crisis. On the one hand, global warming has already begun to significantly disrupt both ecosystems and the ocean currents that regulate the climate on the different continents (Criado 2023). If we are to avoid the suffering, destruction, and death of human and non-human lives on unimaginable scales, stopping the extraction of fossil fuels cannot be postponed any longer. What we can take away from the organized struggle to protect the Yasuní is that this is possible, but also that we must rein in our optimism: these struggles are quantitatively very limited on a global scale, and they might take time that we no longer have. What we see in Jujuy, on the other hand, is that which is hidden by the uncritical discourse of the “energy transition”: under the apparent innocuousness of renewable energies, we recognize the unmistakable “whatever it takes” capitalist logic. This logic is sustained by authoritarian practices and deployed through the dispossession of lands for a “green” capitalism that is, unsurprisingly, fundamentally incompatible with the overcoming of the socio-ecological crisis. It feels, at times, as if the walls are closing in on us: impending crisis or impending doom, few possible pathways seem to exist, most of them have hidden traps, and none appear sufficient to escape it. How to make sense of this scenario?

In this text, I aim to contribute to the discussion regarding the contemporary subjective conditions for radical socio-ecological change. For this, I first briefly introduce the link between the contemporary socio-ecological crisis and the capitalist mode of organization. Then I focus on what will be the centre of my argument, by presenting a discussion on analytical tools from the tradition of Frankfurt School critical theory, including some contemporary formulations. I argue that the lines of inquiry charted by this tradition are relevant for current discussions regarding the political subject during the climate crisis.

CAPITALISM AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF NATURE

The socio-ecological crisis is rooted in a fundamentally contradictory mode of organizing social relations, and one which is necessarily sustained by relations of exploitation and domination: capitalism. The historical development of these capitalist social relations as an alienated social metabolism, which moves according to the logic of “an ever-accelerating process of production for the sake of production” (Postone 1993, 184), necessarily requires an ever-greater mobilization of matter and energy (mostly generated through the burning of fossil fuels). As the metabolism with nature is deeply and continuously transformed, socio-ecological cycles are destabilized, producing what John Bellamy Foster (1999, 2013)–following Marx–calls metabolic fractures. Depending on the severity and depth of these fractures, they can cause anything from the waning or disappearance of species to the collapse of particular ecosystems. Climate change is but a paradigmatic example of the capacity of the capitalist social metabolism to transform nature, only this time on a planetary scale. It demonstrates that the mode of organizing capitalist social relations has become a sort of geological force, capable of altering even the planetary metabolism and transforming climatic conditions that had remained relatively stable over the last 10,000 years.

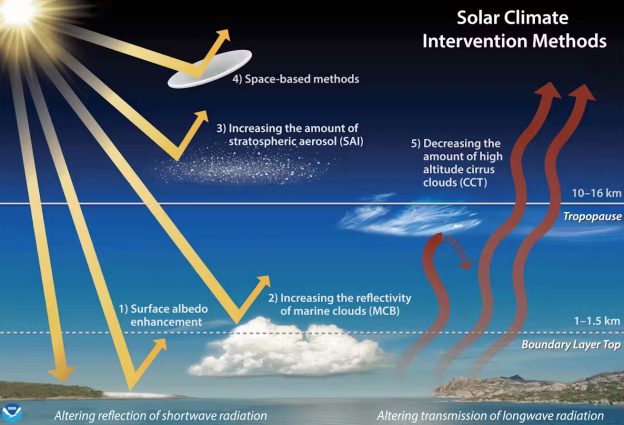

Capital has previously demonstrated the capacity to react to metabolic fractures through, for example, the development of new technologies. However, these “fixes” have not resolved the fractures, but rather have deferred them in time or displaced them to other geographies and dimensions of the global ecosystem. In a similar manner, there are attempts to mitigate the metabolic fractures associated with climate change through massive investment in “renewable” energies (wind, solar) and the electrification of transportation. These will, however, drive a spectacular increase (six times more than at present) in the extraction of minerals such as copper, lithium, nickel, manganese, cobalt, and many others, with the associated environmental degradation of lands and bodies of water. Therefore, unless the socio-ecological transformations we seek move us away from the capitalist way of organizing social relations, the mere displacement of the metabolic fractures is inevitable. We require a theory and praxis that radically breaks with what is at the heart of the capitalist mode of organization: the self-valorization of value and the resulting dynamics of production for production’s sake.

There is a rich and diverse anti-capitalist and ecological tradition of both thought and political organization, all of which attempts to enact different versions of this: to criticize and transform existing society with the intention of building world(s) governed both by the satisfaction of social needs and the sustainment of ecological balance (Löwy 2020; Foster 2023; Svampa 2022; Rátiva Gaona et al. 2023). Still, there is no consensus on the kind of politics that must be acted on in the present in order to build the desired socio-ecological mode of organization. What should collective energy and organization be directed towards? Revolution, social protest, and concrete demands for public policies (e.g. the Green New Deal), the sabotage of fossil fuel infrastructure, organized resistance to extractivist projects, prefigurative politics?

Faced with the question of what to do, the discussion tends to be articulated in the tension between two central themes: that which is possible and that which is necessary. In a context of climate urgency, whatever can be done must be done as soon as possible. This leads to the establishment of “pre-revolutionary” strategies that aim to mitigate the disastrous consequences of living in a capitalist society on a warming planet. This may imply, for instance, resisting particular extractive projects or promoting the transformation of national economies into “green” economies. However, these types of action fall short of the severity of the situation. We are forced to reckon with the necessity of a radically alternative political and socio-ecological project (Svampa 2020), one which, as described above, represents a radical break with capitalism: anything short of that will inevitably lead to a collapse. Such a project, however, faces a “deficit of obvious candidates” (Seaton 2022). There seems to be a kind of consensus around the current lack of collective political subjects with sufficient social power and mobilization to both halt fossil fuel extraction and resist green capitalism, not to mention to dismantle the totality of the social relations that constitute capital…

And now our argument has brought us back, apparently none the wiser, still unable to make sense of the difficulty in transcending the capitalist society that has brought us to this socio-ecological crisis. Can we still aim to do more than carry out localized resistance? Why does it sometimes seem that the possibility of an emancipatory transcendence is foreclosed?

CAPITALISM AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF (INTERNAL) NATURE

We find ourselves in an enigmatic position: aware of being, as a society, on the verge of extinction, while unable to glimpse at even a remote possibility for massive global uprisings capable of stopping the machinery that is inexorably leading us to catastrophe. Possible explanations for this abound: it has been argued that this has to do with insufficient knowledge of climate change, its severity and temporality, its structural causes, or the transformations needed to stop it. Other perspectives focus on the power relations: the tremendously concentrated economic and political power of transnational and state-owned fossil fuel companies, versus the relative weakness of the affected communities that could confront them. Although important, these arguments are not enough to make sense of the “enigma of docility” (Zamora 2007) in the face of a foreseeable collapse.

It is not the first time that an enigma of this nature has intrigued those concerned with radical social transformation. In the decades following the Russian Revolution of 1917, thinkers of the European Marxist tradition tried to make sense of the “failure of the revolution in the West” (Zamora 2007, 27). How to explain that, contrary to what was expected by dominant theory–according to which the sharpening of economic contradictions would generate the conditions for revolution–revolutionary attempts in Western European countries were practically non-existent? The social conformity of dominated subjects could no longer be convincingly explained solely by the capitalist use of coercive violence or ideology (ibid.). Therefore, this demanded that Marxist theory incorporate developments from other theoretical approaches capable of elucidating the psychological and unconscious dimensions of human action. The tradition of Frankfurt School critical theory–through the work of intellectuals such as Max Horkheimer or Theodor W. Adorno–drew from Freud’s psychoanalytic theory to explore the way that social domination was extended to the psychic life of individuals.

The Marxist concept of commodity fetishism was fundamental in this endeavour. It enabled dealing with the inverted appearance of the objective social relations within capitalist society, in which relations between people–commodity producers–appear to be relations between things–the products of their objectified labour (Marx 2022 [1873]). In such a distorted world, that which is social and the product of historical development appears to be natural and object-like (Adorno 2000 [1968]). More than subjective appearances, these are objectively necessary illusions which hide–by naturalizing it–the fundamentally antagonistic character of capitalist society. The culture industry was fundamental for the internalization of commodity fetishism. When Horkheimer and Adorno coined the concept of “the culture industry” (Horkheimer and Adorno 2002 [1944]), they used it to critically refer to the mass production and consumption of cultural products (movies, radio programmes, cars, and advertisements, etc.), which constituted a totalizing framework of socialization in the Fordist United States of the 1940s and 50s (Maiso 2010). Through their consumption of cultural-industrial products, individuals were increasingly socialized to passively internalize the systematic standardization, repetition, and sameness of industrial commodity production (Prusik 2020), profoundly impoverishing their capacity for genuine life experiences. This also ultimately functioned as a compensatory mechanism, a distraction from the suffering of capitalist social life (ibid.).

Simultaneously, other transformations in objective social relations were taking place. The emergence of a deeply technified, “potentially all-embracing” mass society meant capitalist socialization could penetrate deeper into the intimate realm of social life (Maiso 2010, 46). Previous modes of the socialization of individuals, traditionally mediated through institutions such as the family, gave way to a mode of socialization in which coercion and social imperatives come to impose themselves “directly, without mediation” (Maiso 2019, 76). Individuals were directly confronted with a strong system that increasingly monopolized the means of existence. In such a context, conformity with the existing order turned out to be the safest and most adequate option to make such a power imbalance psychologically bearable (ibid., 50). This led Horkheimer and Adorno (2002 [1944]) to posit that society could no longer be thought of in terms of the autonomous, liberal individual, but increasingly as the sum of atomized, impotent, and vulnerable “pseudo-individuals”, to whom the rest of men exist “only in estranged forms, as enemies or allies, but always as instruments, things” (Horkheimer and Adorno 2002 [1944], 49).

Adorno and Horkheimer noted that society’s unmediated violence against the individual was not without a cost: it was paid at the price of profound internal suffering. Adapting to the social machinery required self-repression of libidinal drives (Horkheimer and Adorno 2002 [1944]). In some cases, the powerlessness felt by the weak ego in its direct confrontation with–and ultimate submission to–social coercion could be compensated by the pleasure that came with identification with a powerful entity (be it an authoritarian government or other forms of collective super-ego) (Robles 2020, 2021). This psychological mechanism of identification with authority gives an (often misplaced) sense of security (ibid.) Perceived threats to this precarious security easily turn into acts of aggression towards an external, usually weaker scapegoat (Jews, women, migrants, etc.), as it is difficult for the weak ego to direct its accumulated repressed aggressive drives against those who actually exercise power and authority over it (Zamora 2013). It is through these socio-psychological mechanisms that authoritarianism, anti-Semitism, fascism, racism, nationalism, or misogyny were already prefigured as latent phenomena in capitalist society.

NEOLIBERAL CONDITIONS OF CAPITALIST SOCIALIZATION

We are living in a different historical moment than that experienced by Horkheimer and Adorno. Profound transformations of work and culture, among other things, herald profound transformations in subjectivation. Socialization is increasingly mediated through impersonal digital networks, which represent an intensified conditioning by commodity fetishism. Individuals are no longer passive recipients of mass produced industrial-cultural products. Consumption under neoliberalism, mediated by the digital world, requires active, flexible, and adaptative participation (through the use of smartphones, video games and virtual reality devices, content creation on social media, etc.) thereby deepening the transformation of the very structure of experience (Prusik 2020). Horkheimer and Adorno (2002 [1944]) already postulated the demise of the autonomous, liberal individual in the form of atomized “pseudo-individuals”. It could be argued that individuality is today further liquidated, ironically, under a veil of individualism: the “compulsory need to stand out” and broadcast one’s singularity in the virtual space may be only a sign of the heightened grip that the social totality holds on the production of the self (Prusik 2020, 155).

Subjective transformations are intensified by post-Fordist changes in the patterns of socialization in the work sphere. Being “willing” to sell one’s labour power is no longer sufficient. The mobilization of the cognitive, creative, communicative, and affective skills of the individuals becomes a capitalist imperative in the new organization of work (Zamora 2013). The whole of the person becomes a potential reservoir for heightened productivity, encouraging individuals to relate to their own selves according to the market competitiveness of their particular subjective qualities (Demirovic 2013). This requires the worker to showcase levels of individuality and authenticity which they increasingly are incapable of providing, as they fade into insignificance when faced with the very objective social relations that demand them. Furthermore, in the context of a precarious job market with diminishing employment opportunities, the entrepreneurial relation to oneself is likely to end in recurring failures to successfully sell one’s subjective abilities in such a way that it guarantees a decent living (ibid.). Heightened demands for adaptation collide with the impossibility of its realization, giving way to increasingly generalized burnout syndromes, extenuation, and depression (Zamora 2013). As the imbalance of power between the precarious individual and the social totality intensifies, the wider process of reification further extends social domination by commodity fetishism to the psychic life of individuals. What could be the implications for our collective capacity to act and transform?

CLOSING REMARKS

Socialization of individuals today is no longer that of an all-embracing mass society held together by the promise of social security and integration (which could only truly materialize in the core countries of the global capitalist system), as originally described by the Frankfurt School tradition. Our contemporary reality is instead “radically insecure” (Gandesha 2018): extreme precarity of living conditions coincides with the possibility of planetary collapse. The unfolding of capitalist social relations has resulted, on the one hand, in the intensification of the transformation of external nature at a planetary scale, but also the transformation of what we could call the “internal nature” of people or the constitution of their subjectivity. This has implications for the ways in which the socio-ecological crisis can be experienced, “processed” and acted upon by contemporary subjects, at a time when a radical socio-ecological transformation is indispensable.

While the subjective conditions for revolution are not immediately apprehensible, organized resistance in the face of social and environmental devastation–as manifested in the #SíalYasuní and the popular uprising in Jujuy–exists, and sometimes even wins. Yet, the danger is still latent that the climate crisis will, nevertheless, strengthen the subjective conditions for authoritarianism or other reactionary forms of politicization. The subject socialized under neoliberal conditions is weaker, atomized, and more exhausted than ever. Can we, under these conditions, still build on localized struggles in such a way that it translates into a sufficiently large and powerful social mobilization able to build the indispensable radical socio-ecological transformation? In this text, I have attempted to argue that the rich tradition of Frankfurt School critical theory (including its contemporary formulations)–although it cannot give a direct, practical, and unequivocal answer to such a necessary question–can help us navigate the enigmas of subjectivity in contemporary capitalism and enrich the reflection on the urgent and necessary socio-ecological transformation from the perspective of its subjective conditions of possibility.

References:

Adorno, Theodor W. (2000 [1968]), Introduction to Sociology, edited by Christoph Godde, translated by Edmund Jephcott, Stanford University Press.

Criado, Miguel Ángel (2023), “La principal corriente oceánica que regula el clima muestra señales de colapso”, El País, 25 July, available at https://elpais.com/ciencia/2023-07-25/l ... lapso.html. Last accessed on 1 March 2024.

Demirovic, Alex (2013), “Crisis del Sujeto—Perspectivas de la Capacidad de Acción. Preguntas a la Teoría Crítica del Sujeto”, Constelaciones, vol. 5.

Foster, John Bellamy (1999), “Marx’s Theory of Metabolic Rift: Classical Foundations for Environmental Sociology”, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 105, no. 2, pp. 366—405.

——— (2013), “Marx and the Rift in the Universal Metabolism of Nature”, Monthly Review, available at https://monthlyreview.org/2013/12/01/ma ... ture/#fn13. Last accessed on 9 March 2023.

——— (2023), “Planned Degrowth: Ecosocialism and Sustainable Human Development”, Monthly Review, available at https://monthlyreview.org/2023/07/01/planned-degrowth/. Last accessed on 20 August 2023.

Gandesha, Samir (2018), “‘Identifying with the aggressor’: From the authoritarian to neoliberal personality”, Constellations, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 1—18.

Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno (2002 [1944]), Dialectic of Enlightenment, edited by Gunzelin Schmid Noerr, translated by Edmund Jephcott, Stanford University Press.

Löwy, Michael (2020), “Ecosocialism and/or Degrowth?”, Climate & Capitalism, available at https://climateandcapitalism.com/2020/1 ... -degrowth/. Last accessed on 20 August 2023.

Maiso, Jordi (2010), “Elementos para la reapropiación de la Teoría Crítica de Theodor W. Adorno ”, doctoral thesis, Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca.

——— (2019), “Socialización capitalista y mutaciones antropológicas. Adorno, el nuevo tipo humano y nosotros”, Con-Ciencia Social, no. 2, pp. 65—80.

Marx, Karl. (2022 [1873]), El Capital. Vol. 1, Siglo XXI Editores.

Planelles, Manuel, and Rodrigo Silva (2023), “La crisis climática lleva al planeta al verano más caluroso jamás registrado”, El País, 2 September, available at https://elpais.com/clima-y-medio-ambien ... trado.html#. Last accessed on 29 February 2024.

Postone, Moishe (1993), Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory, Cambridge University Press.

Prusik, Charles (2020), Adorno and Neoliberalism: The Critique of Exchange Society, Bloomsbury Academic Publishing.

Rátiva Gaona, Sandra, Daniela Del Bene, Melisa Argento, Sofía Ávila, Ana María Veintimilla, Daniel Jeziorny, and Felipe Milanez (2023), “Transición energética. Consenso hegemónico y disputas desde el Sur”, Ecología Política, no. 65.

Robles, Gustavo (2020), “El fin de algunas ilusiones: Subjetividad y democracia en tiempos de regresión autoritaria”, Resistances: Journal of the Philosophy of History, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 14—27.

——— (2021), “Crisis de la experiencia y (pos)fascismos. Lecturas desde la Teoría Crítica”, Constelaciones, Revista de Teoría Crítica, no. 13, pp. 312—39.

Rosero, Santiago (2023a), “La larga lucha por salvar al Yasuní de la explotación petrolera”, El País, 27 May, available at https://elpais.com/america-futura/2023- ... olera.html. Last accessed on 29 February 2024.

——— (2023b), “Una consulta popular le dice sí a proteger el Yasuní”, El País, 21 August, available at https://elpais.com/america-futura/2023- ... asuni.html. Last accessed on 29 February 2024.

Seaton, Lola (2022), “Afterword”, Who Will Build the Ark? Debates on Climate Strategy from New Left Review, edited by B. Kunkel and L. Seaton, London: Verso Books.

Svampa, Maristella (2020), “¿Hacia dónde van los movimientos por la justicia climática?”, Nueva Sociedad, no. 286, available at https://www.nuso.org/articulo/hacia-don ... climatica/. Last accessed on 29 February 2024.

——— (2022), “Dilemas de la transición ecosocial desde América Latina”, Oxfam Intermón working paper.

——— (2023), “Jujuy, postal de la Argentina frágil y en peligro”, Revista Anfibia, 17 July, available at https://www.revistaanfibia.com/jujuy-po ... la-svampa/. Last accessed on 1 March 2024.

YASunidos (undated), “Preguntas Frecuentes”, available at https://www.yasunidos.org/preguntas-frecuentes/. Last accessed on 1 March 2024.

Zamora, José (2007), “El enigma de la docilidad Teoría de la sociedad y psicoanálisis en Th. W. Adorno”, El pensamiento de Th. W. Adorno: balance y perspectivas, edited by M. Cabot Ramis, pp. 27—42.

——— (2013), “Subjetivación del Trabajo: Dominación Capitalista y Sufrimiento”, Constelaciones, no. 5.

https://mronline.org/2024/03/30/reflect ... ng-planet/

******

Yellen Plans To Confront China For ‘Unfair’ Clean Energy Subsidies

Posted on March 29, 2024 by Yves Smith

Yves here. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen is going to China next month and plans to press China on its green energy industrial policy. There is an interesting question as to where to draw the line between subsidies that are anti-competitive versus ones considered to be kosher.

The US has a lot to answer for here, in terms of how badly we have neglected our industrial base and allowed financiers to engage in short-termism that has vitiated R&D programs intended to give a leg up. I have referred from time to time to a case study in Marianna Mazzucato’s The Entrepreneurial State, in which the Federal government sponsored LED flat panel research, with the intent of giving a head start to US manufacturing. Venture capitalists refused to back any LED companies, pooh-poohing the potential returns.

The flip side is expert like Michael Pettis have pointed out the simply massive proportion of GDP that China had been devoting to real estate development. Now that prices are seriously in reverse, to the point of being deflationary, China turned to promoting investment in green energy. This has purportedly occurred on such a scale as to blunt the impact of the housing bubble unwind. As Dima of Military Summary would say, “That’s a lot!”

I am frustrated at the lack of much in the way of data (to its credit, the post below does provide some). The loan increase below does not prove the scope of government support. Nevertheless, such a big rise does not look entirely organic:

Of course, there is also a philosophical issue. Many experts concede that getting enough consumer uptake of green energy sources and products will in fact require a lot of government support, and that includes potentially hefty subsidies. So if the US and EU are not willing to provide enough backing to get these products used on a widespread basis, should we be kvetching that China is filling the gap? This is yet another case where some movement in the direction of trying to save the planet gets tangled up in commercial interests and the desire to preserve employment.

Hopefully we will soon see some informed commentary as to whether Yellen’s charges are in line with WTO rules, or are mainly politically-driven noise-making.

By Alex Kimani, a veteran finance writer, investor, engineer and researcher for Safehaven.com. Originally published at OilPrice

Yellen: I intend to warn Beijing that its national underwriting for energy and other companies is creating oversupply and distorting global markets.

Yellen made the comments after visiting Georgia to see a newly reopened solar cell manufacturing plant.

A couple of days ago, China filed a complaint against the U.S. at the World Trade Organization, for electric vehicle subsidies arguing the requirements are discriminatory.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has revealed that she intends to warn Beijing that its national underwriting for energy and other companies is creating oversupply and distorting global markets when she pays the country an official visit.

“I intend to talk to the Chinese when I visit about overcapacity in some of these industries, and make sure that they understand the undesirable impact that this is having–flooding the market with cheap goods- -on the United States, but also in many of our closest allies, Yellen said in a speech in Norcross, Georgia.

“I will convey my belief that excess capacity poses risks not only to American workers and firms and to the global economy, but also productivity and growth in the Chinese economy, as China itself acknowledged in its National People’s Congress this month,” she added.

Yellen made the comments after visiting Georgia to see a newly reopened solar cell manufacturing plant, which closed shop in 2017 because of stiff competition from factories in China. The factory has, however, re-opened thanks to generous solar and clean energy tax credits in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act.

A couple of days ago, China filed a complaint against the U.S. at the World Trade Organization, for electric vehicle subsidies arguing the requirements are discriminatory.

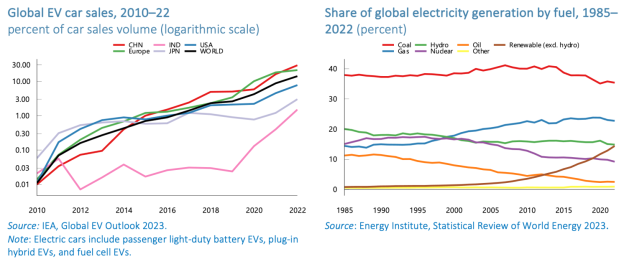

China has pumped in more than $50 billion in wafer-to-solar panel production lines, 10x more than Europe, and also controls a staggering ~95% of the world’s polysilicon and wafer supply. Last year, the International Energy Agency warned of the dangers of the world relying so heavily on China’s solar anc clean energy sector.

“The world will almost completely rely on China for the supply of key building blocks for solar panel production through 2025. This level of concentration in any global supply chain would represent a considerable vulnerability,” the agency wrote in a special report.

China is so dominant that it’s now, single-handedly, changing global solar standards: Last year, a Chinese IT columnist declared that large silicons sized between 182mm and 210mm would become the world’s standard thanks to their market share growing from 4.5% in 2020 to 45% in 2021, adding that they would probably increase to 90% in the near future.

Other than heavy investments and subsidies, Beijing has started taking extra measures in order to maintain its leading status and global market share in renewable energy manufacturing. Last year, in a mirror image of what the U.S. has been doing with its semiconductor lithography technology, China amended its rules to ban the export of several core solar panel technologies. Following the ban, Chinese solar manufacturers are forbidden from using their large silicon, black silicon and cast-mono silicon technologies overseas, according to guidelines published by the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Science and Technology.

“China’s export restraints are Exhibit A on the need to rapidly scale American solar manufacturing,” Abigail Ross Hopper, president and CEO of the U.S. business lobby Solar Energy Industries Association, told WSJ after the Biden administration launched the IRA, which has been hailed as a game-changer for the solar sector.

Although China produces more than 80% of the world’s solar panels and modules, solar exports have faced heavy tariffs imposed by the U.S. over the past decade. This has forced some Chinese manufacturers to move their facilities to countries like Malaysia and Thailand in a bid to avoid the tariffs. However, Beijing does not approve this trend because it does not want them to take their core technologies abroad. Technology experts have pointed out that China wants to prevent India from becoming a major competitor and one of the world’s leading solar panel suppliers.

Back in 2011, the U.S. Commerce Department ruled that China was dumping solar panels in the U.S. market and imposed duties on Chinese solar panels a year later. In June 2022, the Biden administration said it would waive tariffs on solar panels imported to the U.S. from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam for 24 months after Chinese solar firms moved their operations there. Previously, the U.S. placed tariffs on solar products from these countries and even on Taiwan, a close ally, after it deemed that Chinese manufacturers had moved their operations offshore to evade U.S. tariffs.

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2024/03 ... idies.html

(The primary goal of 'Green Capitalism' is not ecological but rather market share.)

Of Life and Lithium

Posted on March 29, 2024 by Yves Smith

Yves here. This post notes that there are problems with lithium, both supply and environmental cost, relative to hoped-for demand for electric vehicles. Of course there are alternate battery types that could replace lithium ones, as well as expectations that car-makers will keep becoming more efficient in their use of materials, including lithium. But it is not clear than any of this will come into play soon enough to prevent a cost crunch and/or damage to aquifers and wildlife.

By Joshua Frank. Originally published at TomDispatch

With his perfect tan and slicked-back hair, California Governor Gavin Newsom stood at a podium at Sacramento’s Cal Expo in late September 2020 and announced an executive order requiring all new passenger vehicles sold in the state to be zero-emissions by 2035. With the global Covid pandemic then at its height, Newsom was struggling to inject a bit of hope into the future, emphasizing that his order would prove a crucial step in the fight against climate change while serving as a major boon to the state’s economy. Later approved by the California Air Resources Board, his order is now being reviewed by the Environmental Protection Agency. For his part, President Biden has moved to tighten regulations on tailpipe exhaust, a not-so-subtle way of pushing car manufacturers to go electric.

As Newsom said shortly before signing his order on the hood of a bright red electric Ford Mustang Mach-E:

“Our cars shouldn’t make wildfires worse and create more days filled with smoky air. Cars shouldn’t melt glaciers or raise sea levels threatening our cherished beaches and coastlines… This is the next big global industry, and California wants to dominate it. And that’s in detoxifying and decarbonizing our transportation fleets… And so today, California is making a big, bold move in that direction.”

One stereotype about Californians is true: we do drive a lot, which also means we buy a lot of new cars. California is, in fact, the top seller of new vehicles in the U.S., with more than 1.78 million cars and trucks rolling off its lots in 2023. In total, significantly more than 14 million vehicles are registered in the state, nearly the same number as in Florida and Texas combined. So Newsom is undoubtedly right that ridding our roads of combustion engines will significantly reduce the state’s climate toll. After all, California’s transportation sector alone is responsible for more than 40% of its greenhouse gas emissions.

On the surface, Newsom’s executive order appears all too necessary, indeed vital, if the use of fossil fuels is to one day be eliminated and climate change mitigated. California is also home to more than 50 electric vehicle manufacturers, and car companies that don’t get on board will soon find themselves “on the wrong side of history,” as Newsom warned. “And they’ll have to recover economically, not just recover in terms of being able to look their kids and grandkids in the eyes.”

Underpinning the governor’s ambitious goal of an all-electric future is another reality. While we may change the kinds of cars we drive, we won’t change our lifestyles to fit a climate-challenged future. Millions upon millions of new zero-emission vehicles will be required and to create them, we’ll need staggering amounts of resources that are still lodged below the earth’s crust. On average, a single battery in a small electric car today contains eight kilograms (17.5 pounds) of lithium, or “white gold.” To put that in perspective, if Californians continue to purchase vehicles at the same pace as in 2023, the amount of lithium required will exceed 113 million kilograms (249 million pounds) annually going forward.

That’s a mountain of lithium and an awful lot of mining will need to be done to make the governor’s plan a reality. And mind you, those figures are lowball estimates — a Tesla Model S battery needs 62.6 kilograms of lithium, for instance — and they don’t address the additional mining electric vehicles will demand to produce considerable amounts of cobalt (14 kilograms), manganese (20 kilograms), and copper (upwards of 80 kilograms) per car. Newsom is correct: ridding California’s sprawling freeways of gas-guzzlers is a necessity and will also be highly profitable, especially for the extraction industry. Nevertheless, it will come with significant cultural and environmental costs that must be accounted for.

A Lithium Bonanza

It’s a scorching hot afternoon in the middle of August and I’m heading west on State Route 293 through Humboldt County in northern Nevada. I’m just a few miles south of where the Thacker Pass lithium mine operation has broken ground. The terrain, managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), part of the Department of the Interior, is sparse and vast. The sky is cloudless, the soil bone-dry. I pass a coyote scampering through the sagebrush. In the distance, the Montana Mountains rise above the flats, casting a long shadow. While dramatically serene, this landscape, located in the middle of the McDermitt Caldera, along with its almost boundless lithium deposits, holds a hauntingly shameful history.

On September 12, 1865, American soldiers carried out a massacre of the Numu (Northern Paiute) near Thacker Pass. Natives call the area “Peehee mu’huh,” or “rotten moon,” to honor the victims. As the story goes, Indigenous Numu were being hunted by the 1st Nevada Cavalry and decided to hide out near Thacker Pass. Dozens of them, including women and children, were eventually found and slaughtered.

An article in the September 30, 1865 edition of The Owyhee Avalanche detailed the carnage. “A charge was ordered and each officer and man went for scalps, and fought the scattering devils over several miles of ground for three hours, in which time all were killed that could be found.” In all, 31 bodies were located, but “more must have been kill[ed] and died from their wounds, as a strict search was not made and the extent of the battlefield so great.”

Today, descendants of the massacre victims are still fighting to designate Thacker Pass and the surrounding area as a memorial site in the National Register of Historic Places. By doing so, they hope the bulldozers will be forced to shut off their engines and lithium mining will cease. In 2021, federal judge Miranda Du rejected their plea, noting that the evidence they presented was “too speculative” to stop the company, Lithium Americas, from prospecting there. In the years since then, the protesters have encountered significant setbacks but have refused to quit.

“All the people here on the reservation were not consulted when this mine was approved,” says Dorece Sam, a descendant of Ox Sam, one of only three survivors of the bloody 1865 massacre at Thacker Pass. Along with six others, he’s currently being sued by Lithium Nevada Corp. (a subsidiary of Lithium Americas) for protesting the mine. “Myself as an Ox Sam descendant, it means a lot to me to know and watch… as the grounds become more and more desecrated. It’s hard to see and hard to watch.”

Lithium Americas pitched its plan to the BLM in 2019 and broke ground at Thacker Pass in March 2023. Native tribes and environmental groups have argued in various court proceedings that the BLM rushed its environmental review without properly consulting the tribes in the approval process. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals shot down their best-chance lawsuit in July.

In a previous 2023 ruling, a lower court stated that the BLM had indeed violated federal law by approving the mine since Lithium Americas hadn’t demonstrated its rights to the 1,300 acres it would, in the future, bury in waste rock from its mining. Despite that acknowledgment, presiding Judge Du failed to revoke the company’s permits.

“Our hearts are heavy hearing the decision that Judge Du did not revoke the permits for the Thacker Pass Lithium Mine. Indigenous people’s sacred sites should not be at the expense of the climate crisis the U.S. faces. Destroying Peehee Mu’huh is like cultural genocide,” said the People of Red Mountain, Indigenous Land and Culture protectors, following Du’s decision.

The “Right” to Mine

While the courts ruled in favor of the Bureau of Land Management’s audit, few are disputing that the Thacker project will have a deleterious impact on the region. For one thing, when the mine is up and running, it will need an exorbitant amount of groundwater for its operations. An estimated 1.7 billion gallons sucked from the Quinn River Valley, an already overburdened aquifer, will have to be pumped into the mine annually. Opponents of the project also note that chemicals used in the lithium extraction process could leach into groundwater supplies, polluting nearby creeks, home to the already threatened Lahontan cutthroat trout. The Thacker basin is also a vibrant wildlife corridor for pronghorn antelope, mule deer, and home to the single largest sage-grouse population in Nevada.

In total, the Thacker Pass mine, the largest known lithium deposit in this country, could one day eat up more than 17,000 acres of public lands, more than half the size of San Francisco. It’s set to be the largest lithium mine in the country, churning out as many as 40,000 metric tons annually, enough to power 800,000 electric vehicles. Inevitably, Thacker will make Lithium Americas’ shareholders very rich, bringing them an estimated nearly $4 billion once all the recoverable lithium is extracted. However, that projection, from 2021, was based on the price of lithium when it sold for an average of $12,600 per ton. By 2023, a ton of lithium was selling for around $46,000.

Promising that the mine will power its all-electric-vehicle future, General Motors now holds exclusive rights to the lithium the mine will extract and has invested $650 million in it. President Biden’s Department of Energy is also all in, loaning $2.26 billion to Lithium Americas to jump-start the project.

The Thacker Pass lithium mine is but one of many examples of the way once venerable Native lands have been and continue to be exploited. The 1872 Mining Act and the Dawes Act of 1887 have long permitted the federal government to stake claims to tribal lands without their consent.

“The Mining Law allows United States citizens and firms to explore for minerals and establish rights to federal lands without authorization from any government agency. This provision, known as self-initiation or free access, is the cornerstone of the Mining Law,” reads a report on that law by Lawrence University economics professor David Gerard. “If a site contains a deposit that can be profitably marketed, claimants enjoy the ‘right to mine,’ regardless of any alternative use, potential use, or non-use value of the land.”

The Dawes Act went even further, allowing the federal government to divide tribal lands into smaller parcels that could be sold off to individual buyers, part of a sinister scheme to delegitimize Native sovereignty on lands that had been stolen from them in the first place.

“It served the larger purpose because the larger purpose was twofold: to make us more like white people or destroy us and get large amounts of land out of Native control and into the hands of individual, non-Native citizens,” says Kelli Mosteller, director of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center. “The Dawes Act solidified once again the distrust that has settled in about dealing with the government. Every time the government comes in and asks for something, there is always that ulterior motive.”

The mine at Thacker Pass, which will end up slicing a gash in the earth a mile wide and 2.3 miles long, is just the latest example of an ugly legacy of ravaging former Native lands for profit.

“Are we still in a situation where the rich get rich and the tribes get poorer because they don’t get a dime off of the mining that happens within their original lands? That’s hard to swallow,” says Arlan Melendez, chair of the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony.

Going Back to California

A significant underground lithium deposit has also been discovered near the south end of California’s dilapidated and toxic Salton Sea, once a playground for Hollywood’s elite. While it’s not nearly as large as the one at Thacker Pass, estimates put the extractable deposits of lithium at upwards of 18 million metric tons, enough to eventually fill 380 million electric vehicle batteries.

Of course, digging out all that smoldering “white gold” will come at a cost there, too, not just economically but environmentally. What those effects will be, exactly, has yet to be revealed. Even so, Governor Newsom made his way to the Imperial Valley and the Salton Sea, a region he hopes might be transformed into a hub for electric battery production and that he’s smugly branded “Lithium Valley.”

“California is poised to become the world’s largest source of batteries, and it couldn’t come at a more crucial moment in our efforts to move away from fossil fuels,” said Newsom. “The future happens here first — and Lithium Valley is fast-tracking the world’s clean energy future.”

How clean that future will be remains to be seen. Here’s one thing to consider, though: no matter how this all turns out, Newsom’s electrified vision of the future doesn’t mean fewer vehicles on the road or a reduction in America’s energy consumption. The California governor isn’t about to challenge the tenets of global capitalism that, with a significant helping hand from global warming, are already driving us toward the brink of ecological collapse. In all too many ways, at least as now planned, more mining, even of lithium, will mean not a new world but an all-too-grim continuation of the status quo. The key difference is that this time around, it will come with a “green” stamp of approval.

In other words, despite the horrors of climate change, the present approach to fixing it, whether by mining for lithium in the Salton Sea or dredging up the spirits of Thacker Pass, is deeply problematic. As long as every single thing on this planet remains a commodity to be exploited for profit, whether labor or natural resources, humanity will remain in crisis. If we proceed as planned down this violent and bumpy road ahead, we may (or may not) save our imperiled climate, but one thing is certain: our little planet will be left in ruins while the wealthy speed off in their Teslas.

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2024/03 ... thium.html