Backed by foreign powers, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and Rapid Support Forces (RSF) are locked in a bloody war with devastating consequences for the Sudanese people.

13 November 2025

Reem Aljeally (Sudan), Ribbon Line, 2025.

Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

In early November, United Nations (UN) Secretary-General António Guterres addressed the ‘horrifying crisis in Sudan, which is spiralling out of control’. He urged the warring parties to ‘bring an end to this nightmare of violence – now’. There is a path to end the war, but there is simply no political will to enforce it. In May 2025, we wrote about the history of the conflict. In 2019, we explained the uprising that took place that year as well as its aftermath. Now, from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, the International Peoples’ Assembly, and Pan Africanism Today, comes red alert no. 21 on the need for peace in Sudan.

What is the reality on the ground in Sudan?

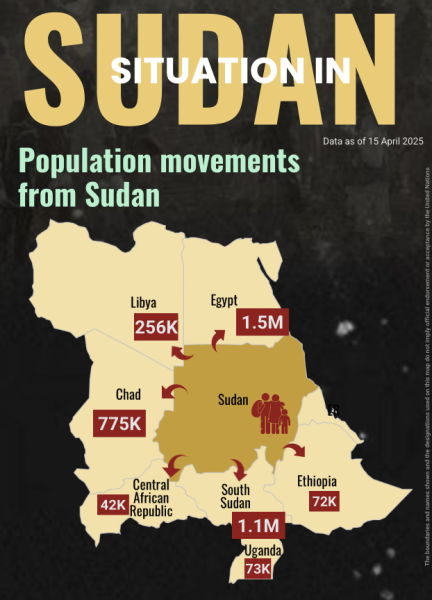

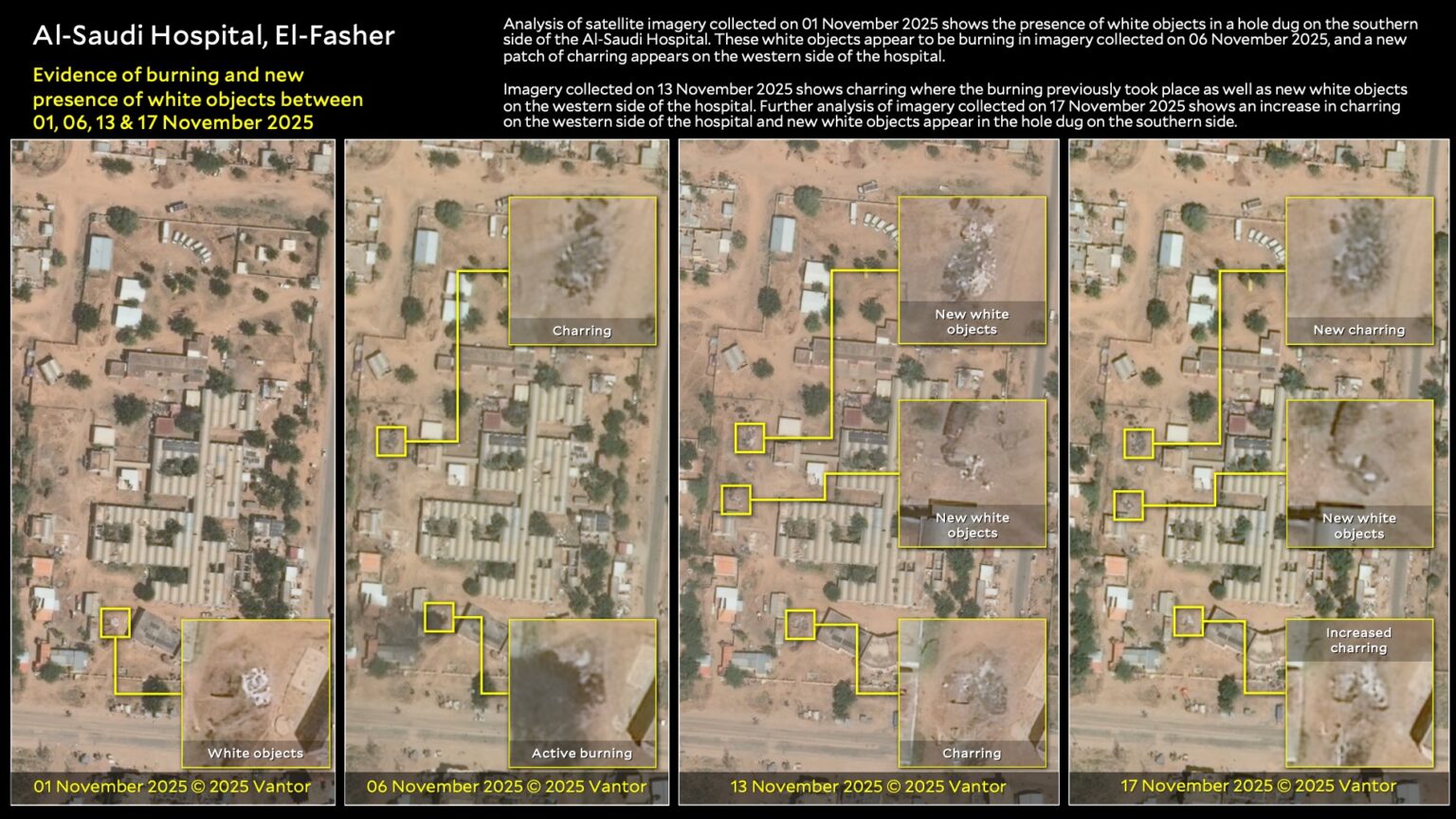

On 15 April 2023, war broke out between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) – led by the head of the Transitional Military Council, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan – and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) – led by Lieutenant General Mohamed ‘Hemedti’ Hamdan Dagalo. Since then, backed by various governments from outside of Sudan, the two sides have fought a terrible war of attrition in which civilians are the main victims. It is impossible to say how many people have died, but clearly the death toll is significant. One estimate found that between April 2023 and June 2024 alone the number of casualties was as high as 150,000, and several crimes against humanity committed by both sides have already been documented by various human rights organisations. At least 14.5 million Sudanese of the population of 51 million have been displaced. The people who live in the belt between El Fasher, North Darfur, and Kadugli, South Kordofan, are struggling from acute hunger and famine. A recent analysis by the UN’s Integrated Food Security Phase Classification found that around 21.2 million Sudanese – 45% of the population – face high levels of acute food insecurity, with 375,000 people across the country facing ‘catastrophic’ levels of hunger (i.e., on the brink of starvation).

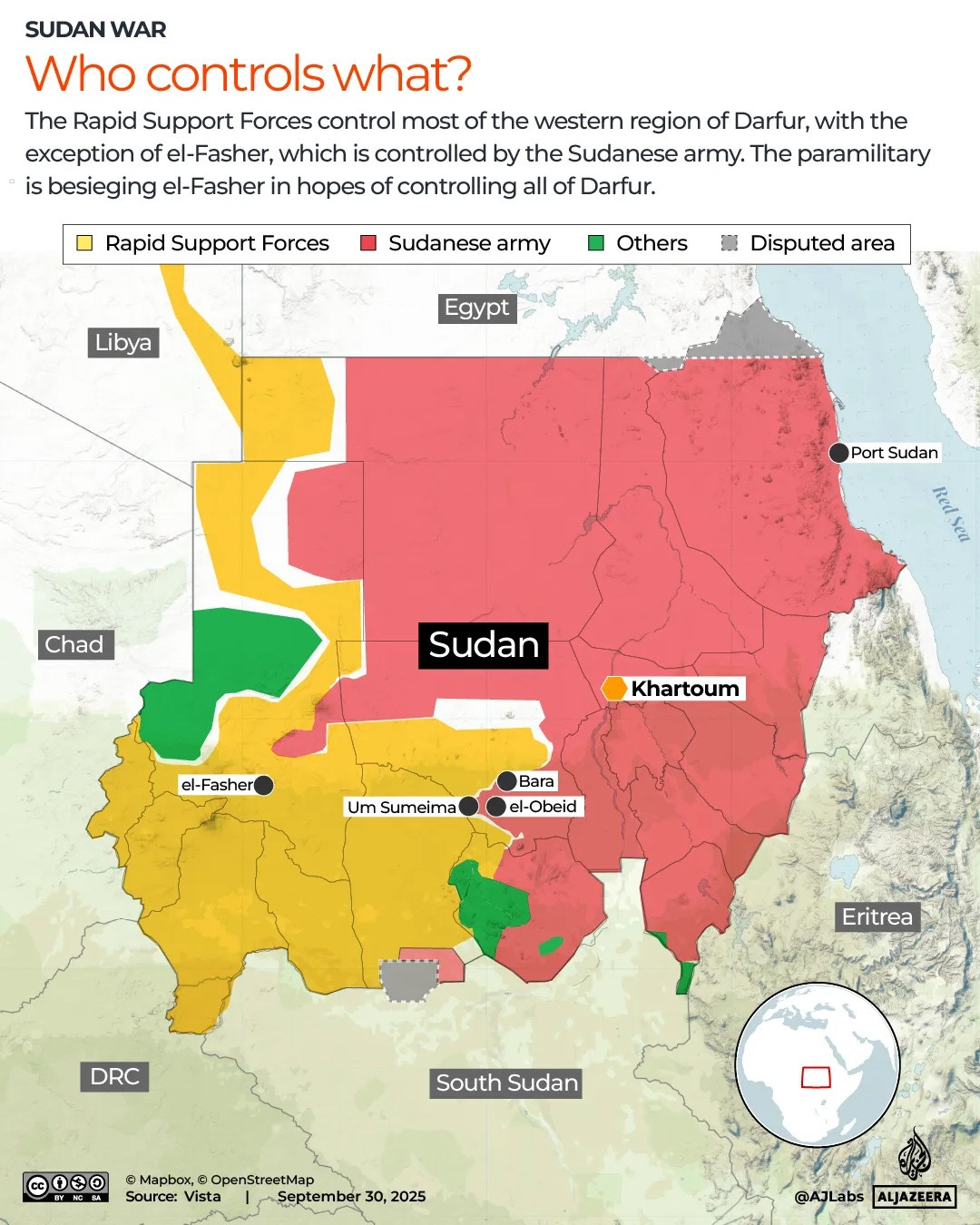

Since the war began, hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people sought refuge in El Fasher, then held largely by the SAF. Roughly 260,000 civilians were still there in October 2025 when the RSF broke the resistance, entered the city, and carried out a number of documented massacres. Among those killed were 460 patients and their companions at the Saudi Maternity Hospital. The city’s fall has meant that the RSF is now largely in control of the vast province of Darfur, while the SAF holds much of eastern Sudan – including Port Sudan, the country’s access to the sea and international trade – as well as the capital city of Khartoum.

There is no sign of de-escalation at present.

Salah Elmur (Sudan), Farewell Wall, 2024.

Why are the SAF and the RSF fighting?

No war of this scale has one simple cause. The political reason is straightforward: this is a counter-revolution against the 2019 popular uprising that succeeded in ousting President Omar al-Bashir, who governed from 1993 and whose last years in power were marked by rising inflation and social crisis.

The left and popular forces behind the 2019 uprising – which included the Sudanese Communist Party, the National Consensus Forces, the Sudanese Professional Association, the Sudan Revolutionary Front, the Women of Sudanese Civic and Political Groups, and many local resistance and neighbourhood committees – forced the military to agree to oversee the transition to a civilian government. With the assistance of the African Union, the Transitional Sovereignty Council was established, composed of five military and six civilian members. Abdalla Hamdok was appointed prime minister and judge Nemat Abdullah Khair chief justice, with al-Burhan and Hemedti on the council as well. The military-civilian government wrecked the economy further by floating the currency and privatising the state, thereby making gold smuggling more lucrative and strengthening the RSF (this government also signed the Abraham Accords, which normalised relations with Israel). The policies of the military-civilian government exacerbated the conditions toward the showdown over power (control over the security state) and wealth (control over the gold trade).

Despite their roles on the council, al-Burhan and Hemedti attempted coups until succeeding in 2021. Having set aside the civilians, the two military leaders went after each other. The SAF officers sought to preserve their command over the state apparatus, which in 2019 absorbed 82% of the state’s budgetary resources (as confirmed by Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok in 2020). They also moved to retain control of its enterprises, running more than 200 companies through entities such as the SAF-controlled Defence Industries System (estimated $2 billion in annual revenue) and capturing a significant share of Sudan’s formal economy across mining, telecommunications, and import-export commodity trade. The RSF – rooted in the Janja’wid (devils on horseback) militia – tried to leverage the autonomous war economy centralised around the Al Junaid Multi-Activities Corporation, which controls major gold-producing areas in Darfur and about half a dozen mining sites, including Jebel Amer. Since 50–80% of Sudan’s overall gold production is smuggled (as of 2022) – mainly to the UAE – rather than officially exported, and since the RSF dominates production in western Sudan’s artisanal mining zones (which account for 80–85% of total production), the RSF captures huge sums from gold revenue every year (estimated at $860 million from Darfur mines alone in 2024).

Beneath these political and material contests lie ecological pressures that compound the crisis. Part of the reason for the long conflict in Darfur has been the desiccation of the Sahel. For decades, erratic rainfall and heatwaves due to the climate catastrophe have expanded the Sahara Desert southward, making water resources a cause of conflict and sparking clashes between nomads and settled farmers. Half of Sudan’s population now lives with acute food insecurity. The failure to create an economic plan for a population wracked by rapid changes in weather patterns – alongside the theft of resources by a small elite – leaves Sudan vulnerable to long-term conflict. This is not just a war between two strong personalities, but a struggle over the transformation of resources and their plunder by outside powers. A ceasefire agreement is once more on the table, but the likelihood that it will be accepted or upheld is very low as long as resources remain the shining prize for the various armed groups.

Omer Khairy (Sudan), Market Scene, 1975.

What are the possibilities of peace in Sudan?

A path toward peace in Sudan would require six elements:

An immediate, monitored ceasefire that includes the creation of humanitarian corridors for the transit of food and medicines. These corridors would be under the leadership of the Resistance Committees, which have the democratic credibility and networks to deliver aid directly to those in need.

An end to the war economy, specifically shutting down the gold and weapons pipelines. This would include imposing strict sanctions on the sale of weapons to and the purchase of gold from the UAE until it severs all relations with the RSF. Export controls at Port Sudan must be implemented as well.

The safe return of political exiles and the start of a process to rebuild political institutions under a civilian government elected or supported by the popular forces – mainly the Resistance Committees. The SAF must be stripped of its political power and economic assets and subjugated to the government. The RSF must be disarmed and demobilised.

The immediate reconstruction of Sudan’s higher judiciary to investigate and prosecute those responsible for atrocities.

The immediate creation of a process of accountability that includes the prosecution of warlords through a properly constituted court in Sudan.

The immediate reconstruction of Sudan’s planning commission and its ministry of finance to shift surplus from export enclaves toward public goods and social protections.

These six points elaborate upon the three pillars of the African Union and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development’s AU-IGAD Joint Roadmap for the Resolution of the Conflict in Sudan (2023). The difficulty with this roadmap – as with similar proposals – is that it is dependent on donors, including actors that are implicated in the violence. For these six points to become a reality, outside powers must be pressured to end their backing of the SAF and the RSF. These include Egypt, the European Union, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and the United States. Neither this roadmap nor the Jeddah channel – a Saudi-US mediation track launched in 2023 that focuses on short truces and humanitarian access – includes Sudanese civilian groups, least of all the Resistance Committees.

Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq (Sudan), Loneliness, 1987.

Though Sudan has produced its share of poets who sing of pain and suffering, let us end on a different note. In 1961, the communist poet Taj el-Sir el-Hassan (1935–2013) wrote ‘An Afro-Asian Song’, which begins by commemorating the Kosti massacre at Joudeh in 1956, when 194 striking peasants were suffocated to death while in police custody. But it is to the end of the song that we turn, the voice of the poet ringing above the gunfire:

In the heart of Africa I stand in the vanguard,

and as far as Bandung my sky is spreading.

The olive sapling is my shade and courtyard,

O my comrades:

O vanguard comrades, leading my people to glory,

your candles are soaking my heart in green light.

I’ll sing the closing stanza,

to my beloved land;

to my fellows in Asia;

to the Malaya,

and the vibrant Bandung.

To the people of El Fasher, to those in Khartoum, to my comrades in Port Sudan: walk toward peace.

Warmly,

Vijay

https://thetricontinental.org/newslette ... dan-peace/

******

Agricultural offensive: how Burkina Faso is moving towards self-sufficiency in food production

The government of Ibrahim Traoré seeks to reduce dependence on imports in a country where 80% of the population are farmers.

November 13, 2025 by Pedro Stropasolas

The distribution of agricultural machinery to farmers has been one of the cornerstones of the Agricultural Offensive of the Traoré Government. Photo: Presidency of Burkina Faso

Dependence on foreign aid, political instability, chronic poverty, and the effects of climate change are among the obstacles preventing Burkina Faso from achieving its longed-for food sovereignty.

Currently, about 80% of the population of the Sahelian nation is involved in agricultural activity, which accounts for a third of the GDP. Even so, the country still imports more than 200,000 tons of rice per year.

In response to this challenge, President Ibrahim Traoré’s government launched the so-called Agricultural Offensive in 2023, which has been revolutionizing the rural environment and serving as a model for the continent. The central objective is to end dependence on imports of widely consumed food products.

According to Mark Gansonré, a farmer and representative of farmers’ associations in the National Transitional Assembly, in implementing the program, the new government sought to listen to the country’s farmers. “I believe he [Traoré] took the time to understand the cry from the hearts of Burkina Faso’s farmers.”

Read More: In the fight against desertification, Burkina Faso mobilizes to plant 5 million trees in one hour

“Since 2002, we have undertaken a series of actions, beginning with the demand for recognition of agriculture as a full and legitimate profession. We obtained an agricultural guidance law to structure this recognition. We also worked to facilitate access to credit for small producers. Today, we have reached a point of true gratitude. Thank God, last year this government allocated 78 billion CFA francs for the purchase of agricultural equipment, making it available to farmers,” celebrates Gansonré.

The numbers of the Agricultural Offensive

The offensive has already yielded results in food self-sufficiency. Yields per hectare in the country have increased dramatically since the start of the offensive, with improvements of around 35% to 40%.

Most notably, the country achieved grain surpluses for two consecutive years, a stark contrast to the historical pattern of deficits prior to the current administration. In 2024, six million tons of grain were harvested in Burkina Faso.

This occurred despite the presence of fundamentalist jihadist groups around the country. By the end of this year, the agricultural program aims to create 100,000 jobs for the population displaced by terrorism. About 54% of the budget is funded by the private sector and 46% from the state.

“If there are more than a million displaced people, the majority of this population is in rural areas. Many of these farmers abandoned lands that could not be cultivated. But this does not prevent us from producing today. Despite the abandonment of several agricultural areas that could not be cultivated, there has been significant support so that in regions where there is still productive capacity, farmers could intensify production in order to feed the Burkinabé people,” Gansonré points out.

Luc Damiba, special advisor to the Prime Minister of Burkina Faso, believes that even in a context of low rainfall, the country has good land and abundant water, which, according to him, makes it possible to reorganize production to supply the citizens. He emphasizes that guaranteeing sufficient food for the population is the basis of any national project.

“We need to work with the peasants, work with them well. If we don’t do that, they will be occupied by the terrorists. That’s the first gain. The second gain is that they will produce enough to achieve food self-sufficiency. The third gain is that we will have well-prepared political actors committed to advancing the revolution,” he analyzes.

“If we don’t have the peasant world to carry out the revolution, we will fail. We can only count on the peasant world to accomplish it. And Traoré started well by adopting this offensive agricultural policy, capable of mobilizing this group, which became a fundamental political actor,” adds Damiba.

Relationship with Sankara

The quest for food sovereignty in the region has deep historical roots, dating back to Thomas Sankara’s revolution in the 1980s. The agrarian reform implemented by Sankara, in addition to distributing land to those who actually produced it, aimed to politically engage this large mass of small farmers. In 1987, after four years in power in Burkina Faso, the UN recognized the country for the first time as self-sufficient in food production.

Read More: Sankara’s revolution rises again

Following the assassination of the former president and leader of the historic Burkinabé revolution, however, decades of policies that prioritized export crops at the expense of family farming led the Sahel country to once again depend on external inputs.

The colonial model, dictated by global agribusiness multinationals, such as Monsanto, gained ground in the country during the regime of Blaise Compaoré, the mastermind behind the Sankara massacre, who governed the country from 1987 to 2014, with the support of the French government.

For Mark Gansonré, the implementation of the Agricultural Offensive is a symbol of Traoré’s alignment with Sankara’s ideas.

“It’s as if we have a Sankara. Sankara has awakened. It’s true that in his time most of the population didn’t quite understand his vision. He was a mobilizer… But today, after his passing, there has been an awakening, and this current government has effectively stimulated that awakening,” he said.

Mechanization

The current government’s offensive has been marked by strong direct support for rural producers and unprecedented investments in mechanization. The strategy focuses on substantially increasing production in eight priority areas: rice, corn, potatoes, wheat, fish, livestock, poultry, and mangoes.

Financing for the purchase of machinery in the country, much of it from China, relies on two main sources: the nationalization of gold and the creation of a patriotic fund financed by the population itself.

Since Traoré took control of two mines that previously belonged to a London-listed company and began construction of a state-owned refinery, the government has already allocated USD 179 million for the purchase of agricultural machinery.

Sawadogo Pasmamde, or Oceán, a multi-artist and member of the Thomas Sankara Center for Freedom and African Union, details the transformation.

“For the first time, tractors are being distributed throughout the country. Agricultural inputs are being delivered to farmers, giving them everything they need to produce. In addition, all the agricultural engineers who worked in the cities have been transferred to the countryside to directly monitor and support the farmers. And now, we see that the results are beginning to appear as a reward for this effort,” Oceán celebrates.

The two types of agriculture

According to the government’s announcement, the differentiated mechanization includes draft animals for small producers, and, on the other hand, tillers and tractors for large enterprises. Initially, more than 400 tractors were distributed, in addition to subsidized fertilizers. For the 2025-2026 campaign, the package should include the delivery of 608 tractors and 1,102 tillers.

According to Marc Gansonré, this is a long-standing demand from the country’s farmers that has never been fully met. He recalls that there was an initial attempt during the revolution led by Sankara, but the process was interrupted after his death.

During the Compaoré administration, he adds that a program even distributed carts to farmers, but without the necessary draft animals for their use. The initiative was stalled for years until, after demands from the farmers, subsidies were introduced for plows and for animals such as donkeys and oxen.

Even so, the reach of the policies remained limited. According to the parliamentarian, at the time there were about 1.4 million farming families in the country, but less than half were served by the programs: “coverage reached only 27%, then 32%”.

“And, thank God, we had the arrival of this current president, who understood from the beginning the signs of this need to support mechanization,” he emphasizes.

According to Marc, mechanization in the country today is carried out in a differentiated way, respecting the spatial dimensions of each cultivable area and the financial capabilities of the producing families.

He explains that in Burkina Faso, there are two types of agriculture: family-run farms and large-scale agricultural enterprises that require heavy equipment.

“Giving a rototiller or tractor to someone who doesn’t have the means to properly maintain that equipment is like doing nothing. That’s why we work to ensure that small producers continue to be supported with plows and draft animals, while those who have progressed a bit more can work with rototillers,” explains Gansonré.

“When rainfall doesn’t exceed 5 millimeters and you need to sow, it’s necessary to cultivate as much of the area as possible within the following 24 to 48 hours. And doing this manually is very difficult. That’s why seeders and tillers were introduced to improve soil preparation,” he adds.

Creation of industries

In addition to production, the Burkinabé government’s focus with its Agricultural Offensive is on industrialization and adding value to locally grown products. In the country, the creation of processing units has generated jobs and even allowed farmers to become shareholders in some of the factories that have been opened.

Read More: Forging a new Pan-African path: Burkina Faso, Ibrahim Traoré, and the Land of the Upright People

The country’s first tomato processing plant, inaugurated in 2024 in Bobo Dioulasso, has 20% state participation and 80% community capital, organized by APEC, the Agency for the Promotion of Community Entrepreneurship. The organization, founded in 2022, is primarily supported by the small and medium-sized national bourgeoisie.

Souleymane Yougbare, director of the National Council for Organic Agriculture of Burkina Faso (CNABio), believes that the initiative has reduced dependence on imports and developed the local economy.

“If we have, for example, 100% Burkinabé tomato puree, this allows us to protect our markets, it allows us to be autonomous in relation to the consumption of tomato puree and also avoid cases of poisoning. We don’t know how anything we import is produced,” says Yougbare.

He also highlights how the factory has added value to the farmers’ production, who previously lost a large part of their harvest due to a lack of alternative distribution channels.

“Before, tomato production in Burkina Faso was very high, but unfortunately, producers lost a good portion because the tomatoes rotted in the fields or had to be sold at very low prices. That’s sad. There were even exporters, or rather, importers and exporters, who came to buy at ridiculously low prices and resold in other countries. All of this destroys our economy,” he assesses.

On the other hand, Yougbare argues that the advancement of industrialization in the country must be accompanied by reflection on its impacts. “When we think about industrialization, and the name says it all, we need to be careful that it doesn’t bring other problems, as we see in developed countries: pollution of the ozone layer, the impact on the climate … Therefore, it is necessary that the solutions be truly local, adapted to our context and our needs,” he explains.

Member of Parliament Marc Gansonré believes that the country is currently experiencing a shift in consciousness, “a spirit of patriotism” that leads the population to say: “If we want to be autonomous, it’s good to receive help, but it’s better that we ourselves work to find solutions to our internal problems. And what we cannot do, we can seek outside.”

He concludes: “I recognize that these are truly new elements that we are observing today, thanks to the vision of the Head of State and his government. This gives us great hope that, soon, West Africa will be an example for other countries.”

https://peoplesdispatch.org/2025/11/13/ ... roduction/

Africa’s recent elections: crisis and a continent’s youth in revolt

The recent elections in Tanzania, Cameroon, and Côte d’Ivoire lay bare the contradictions of neoliberal democracy in Africa, where the ruling class clings to power through coercion and electoral manipulation to protect imperial and class interests.

November 14, 2025 by Nicholas Mwangi

Mass protest in the Ivory Coast. Photo: PCRCI

The past few months have seen three elections across Africa, in Tanzania, Cameroon, and Côte d’Ivoire. Each exposed a deepening democratic crisis on the continent. While the ballot boxes were filled and the slogans of “stability” and “unity” were loudly proclaimed, the underlying reality was very different; repression, exclusion, and a profound disconnect between the political class and the masses, especially youth.

In all three cases, aging leaders clung to power through electoral processes that were anything but democratic. The continuity of these regimes is part of Africa’s enduring entrapment within neoliberal and neo-colonial frameworks, where the ritual of elections serves to legitimize old orders and satisfy liberal democracy’s important symbolic tenet of holding elections without any fundamental change.

Tanzania: a crisis of legitimacy

The October 29, 2025 elections in Tanzania marked a turning point toward deeper authoritarianism. President Samia Suluhu Hassan was declared the winner with 97.66% of the vote, a margin that raised more questions than celebrations. The opposition, led by CHADEMA party figures such as Tundu Lissu and Amani Golugwa, faced relentless harassment long before polling day. Opposition rallies were dispersed, candidates were barred, and dozens of party members were arrested.

Following the announcement of results, Tanzanians poured into the streets of Dar es Salaam, Arusha, and Mwanza, only to meet state brutality. A total internet shutdown, curfews, and reports of mass killings and disappearances turned the election aftermath into one of the darkest chapters in Tanzania’s political history. Human rights groups have since alleged grave violations, though independent verification remains difficult under government censorship.

Read More: Post-election repression in Tanzania as President Suluhu “wins” with 97.66%

Regional responses were telling. The African Union (AU), initially quick to congratulate President Suluhu, later walked back its stance under public pressure, admitting the elections had “failed to meet democratic standards”. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) reported that even its own observers were harassed and detained by Tanzanian security forces. But, beyond rhetorical concern, no meaningful interventions followed.

Cameroon: the century of Paul Biya

Meanwhile, in Cameroon, Paul Biya, now 92 years old and in power since 1982, extended his rule for another seven-year term. The October 12, 2025 election, where Biya supposedly won 53.66% of the vote, came after mass disqualifications of opposition candidates 70 out of 83 applications were rejected by the Electoral Commission (ELECAM). Among those barred was Maurice Kamto, the major opposition figure who had previously challenged Biya in 2018.

With viable opposition effectively neutralized, Issa Tchiroma Bakary became the nominal challenger. His supporters protested even before the official results, alleging manipulation and fraud. Protests in Douala, Garoua, and Maroua were met with live ammunition and mass arrests. The images of unarmed protesters being shot at while demanding transparent elections have further tarnished Cameroon’s already fragile legitimacy.

Cameroon’s youth, facing unemployment rates above 30%, have become increasingly alienated from a political system that offers neither opportunity nor representation.

Côte d’Ivoire: the illusion of reform

In Côte d’Ivoire, President Alassane Ouattara, 83, secured a fourth term, continuing a pattern of constitutional manipulation that has defined Ivorian politics since independence. Having argued that the 2016 constitutional reform “reset” term limits, Ouattara sidelined his main rivals, Laurent Gbagbo and Guillaume Soro, both of whom were barred from contesting.

The election had no real competition and a state apparatus designed to reproduce the status quo. Opposition groups organized protests, only to face mass arrests and bans on demonstrations. The government’s heavy-handed tactics show what is becoming a broader regional trend, electoral processes are increasingly hollowed out, while Western donors and Bretton Woods institutions continue to embrace “stability” over justice.

Ouattara’s rule represents a particularly insidious strain of technocratic neoliberalism governance through economic orthodoxy rather than political legitimacy. Once hailed by the IMF and World Bank as a model reformer, Ouattara has overseen rising inequality, rural poverty, and youth unemployment, even as Côte d’Ivoire posts impressive GDP figures. As Jonis Ghedi Alasow of Pan African Today noted, “the reported approval ratings of over 90% in some of the elections (Tanzania and the Ivory Coast) stand in stark contrast to the palpable discontent in these societies. This discontent is not only evident in opposition politics during electoral cycles but also in the daily challenges and frustrations that citizens voice, extending far beyond electoral processes. These are not elections — they are coronations. Ouattara’s popularity in Western capitals stems from his willingness to implement austerity and privatization, not from the consent of his people.”

Beyond the ballot: what to make of Africa’s electoral crisis

The Accra Collective of the Socialist Movement of Ghana (SMG) released a statement calling out the wave of electoral fraud, constitutional manipulation, and state repression sweeping the continent. Declaring that “ruling elites have turned elections into tools for preserving power rather than instruments for expressing the popular will.”

Their critique points to a larger truth: Africa’s democratic crisis is not just political, it is structural. Elections are embedded within a neo-colonial framework, where sovereignty is constrained by debt, trade dependency, and elite alliances with global capital. Leaders like Biya, Ouattara, and Suluhu remain in power precisely because they are reliable custodians of imperial interests, managing resource extraction and neoliberal reforms under the guise of “stability”.

As Ghedi Alasow adds, “It is important to remember that elections have never been a panacea for the fundamental problems facing our people. Africa’s history is a testament to the fact that meaningful change emerges not from ballot boxes but from organized struggle.”

But, at the same time, popular anger is growing on the continent, the youth of Africa are beginning to question not just fraudulent elections, but the very legitimacy of the systems that sustain them. Movements inspired by Pan-Africanism, socialism, and grassroots organizing are re-emerging and organizing, calling for a politics that serves the people rather than capital.

Ghedi Alasow remarked, “The popularity of leaders like Traoré underscores what people truly seek: patriots who are willing to defend their interests. People are less concerned about the means through which leaders come to power, but more about whose interests those leaders champion once in office. The neocolonial order is in crisis. It can no longer credibly claim legitimacy or democratic character.”

Who makes the future

The crises in Tanzania, Cameroon, and Côte d’Ivoire are symptoms of a larger continental malaise; the collapse of bourgeois democracy under the weight of inequality, corruption, and neocolonial dependency. Electoral rituals continue, but their content has been emptied. Without popular participation, economic sovereignty, and mass organization, elections will remain instruments of domination, not change in any foreseeable future.

True democracy, as the Socialist Movement of Ghana reminds us, “must rest on popular sovereignty where power flows from the organized masses, not from the boardrooms of multinational corporations or the dictates of imperial powers.”

Africa’s future, then, will not be decided by the aging autocrats who cling to office, nor by the technocrats who serve imperial finance. It will be forged by a generation that refuses to be silenced, a generation determined to reclaim democracy from the shadows of neocolonialism and to rebuild it in the light of people’s power.

https://peoplesdispatch.org/2025/11/14/ ... in-revolt/