ESSAY: National Liberation: Categorical Imperative for the Peoples of Our Americas, Manuel Maldonado-Denis, 1982

Editors, The Black Agenda Review 07 Jan 2026

“The national independence struggles of the peoples of Our America have simultaneously been anti-imperialist struggles from Tupac Amaru up through our times.”

“The national independence struggles of the peoples of Our America have simultaneously been anti-imperialist struggles from Tupac Amaru up through our times.”

From September 4th to 7th, 1981, writers, poets, and scholars converged in Havana, Cuba, for the Primero Encuentro de Intelectuales por la Soberanía de los Pueblos de Nuestra América — the first Conference of Latin American and Caribbean Intellectuals for the Sovereignty of the Peoples of Our America. Hosted by Casa de las Americas, participants came from across the region, bringing with them a range of ideological and political stances.

But they came together around one thing: the threat of Ronald Reagan and the United States to the peace, security, and sovereignty of the Americas. Indeed, in the introduction to Nuestra América: En lucha por su verdadera independencia, the print publication of the conference proceedings, the editors noted the rare political urgency that marked the atmosphere of the conference. But it also pointed to what Uruguayan journalist, novelist, and poet Mario Benedetti described as the "unprecedented unity" of the conference participants in the face of the threat of Reagan. The editors continued:

with his neutron bomb, with his hysterical escalation of the arms race, with his insistence on stoking the Cold War, with his hatred of socialism and the cause of national liberation, and his frequent aggressions against countries struggling for their full independence, Ronald Reagan unwittingly helped the participants at the meeting realize that while the aggressiveness of American imperialism exhibits more weakness than strength, it is nevertheless a powerful enemy that is infringing upon the fundamental rights of our people and that we must confront the enemy decisively, using all the resources at our disposal to overcome it.

In short, Ronald Reagan not only unmasked the true face of US imperialism, but also exposed inherent weaknesses and vulnerabilities.

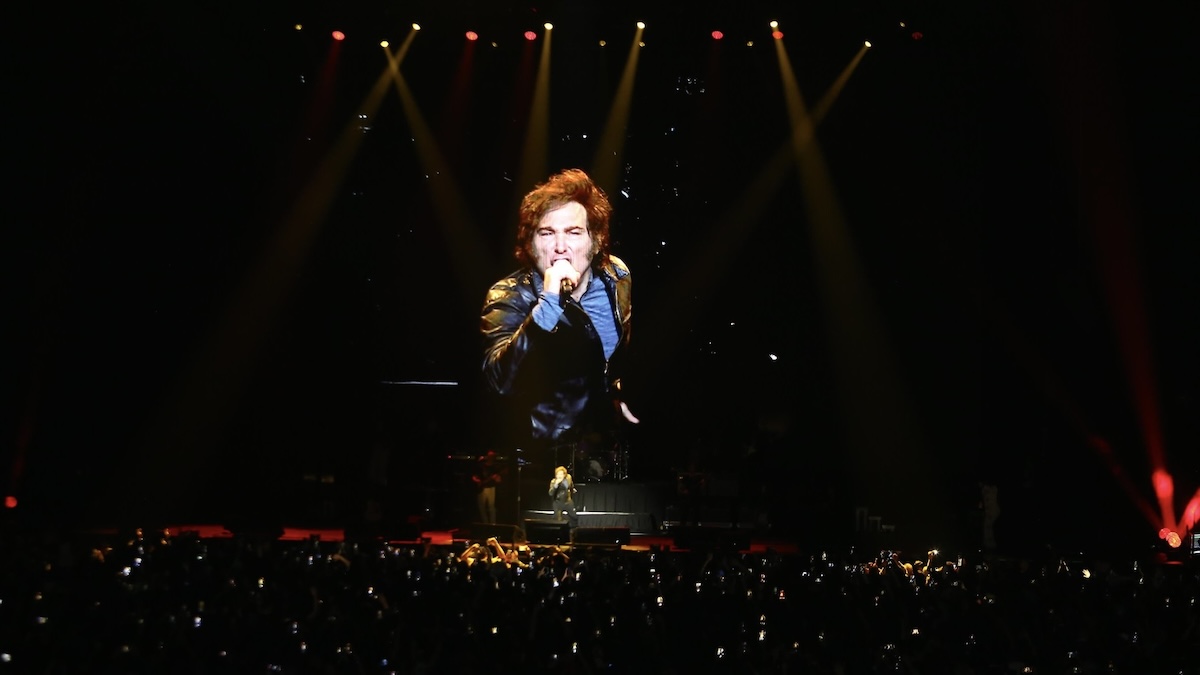

One of the most remarkable and stirring contributions to the congress was an address by the Puerto Rican political scientist Manuel Maldonado-Denis (1933-1992). Published in Spanish in Nuestra América as the essay, “La liberation Nacional: imperative categorically de Nuestra America,” it appeared in 1982 in English in the Havana-based journal Tricontinental, as “National Liberation: Categorical Imperative for the Peoples of Our America.”

Denis’s essay captured the militant energy of the Havana congress. He invokes the long history of Indigenous and African resistance in the Americas, and of peasant and worker struggles for freedom. He also reminds us of the main tasks of national liberation: “a) the struggle for national independence; b) the struggle against other subtle, and not so subtle, forms of colonization that continue even after national independence has been won; c) the struggle for economic independence, that is, the struggle to recover for the use and enjoyment of the nation and all those means of production remaining in private hands; [and] d) the socialization of these means of production and the process of building socialism.”

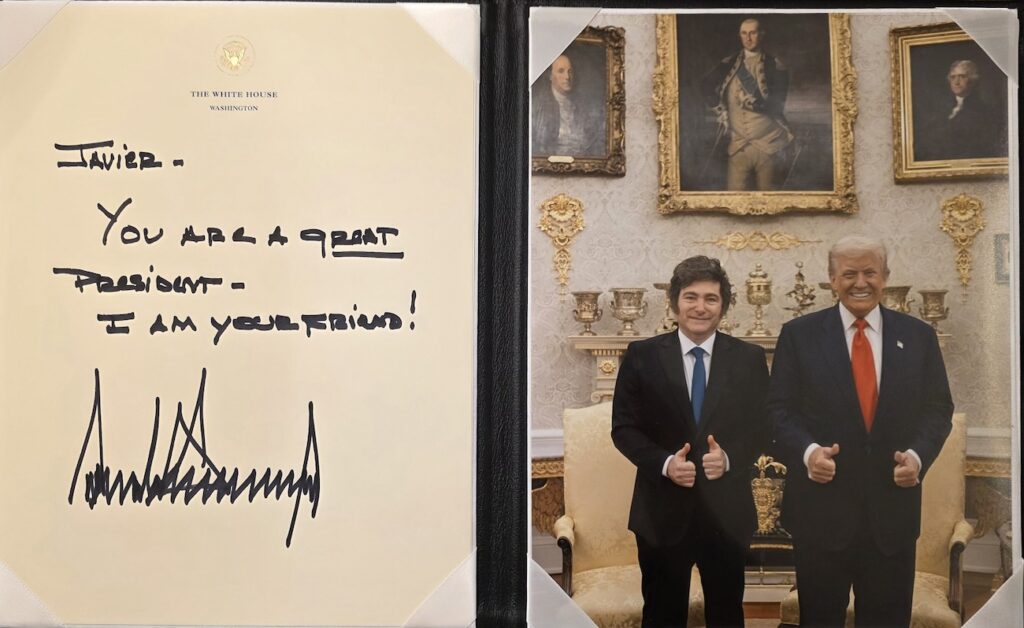

Importantly, for Maldonado-Denis national liberation can only be achieved if regional unity is established for its defense. It is no wonder that Donald Trump, like Reagan before him, is continuing the unhinged violence of US imperialism in the region and doing everything in his power to breed division and suspicion amongst the nations and peoples of our Americas. It is long past the time that the peoples of our Americas realized their mutual interests to come together and fight back against the monster.

We reprint Manuel Maldonado-Denis’s essay, “National Liberation: Categorical Imperative for the Peoples of Our Americas” below.

National Liberation: Categorical Imperative for the Peoples of Our Americas

Manuel Maldonado-Denis

When Emmanuel Kant, the idealist philosopher, set out to explain the essence of each person’s moral obligation to the rest of mankind, he proceeded to define it in the following way: “Always try to act in such a way so that the principle of your behavior can serve as a general rule.” This categorical imperative, as it was called in the ethics of this renowned philosopher from Konigsberg, was echoed in Jose Martí’s famous advice: “Every true man must feel upon his own cheek the slap upon any other man’s cheek.” This responsibility of mankind arises from the very process of human solidarity: to fight injustice and oppression wherever it arises. This is true both for individuals and for peoples. Hence Martí tell us in the Manifesto of Montecristi: “It is touching and an honor to think that when an independence fighter falls upon Cuban soil, perhaps abandoned by the unwary of indifferent nations for which he sacrificed himself, he falls for the greater good of mankind, the affirmation of the moral republic in America, and for the creation of a free archipelago where the respectable nations may lavish their wealth which, as it circulates, must fall upon the crossroads of the world.” Can one imagine a better or fuller expression of this internationalist spirit, which guided Martí and continues to inspire all those who see the struggle against imperialism as one clearly transcending national boundaries, inserted in the very center of the fight against injustice and oppression, whether in Palestine or South Africa, El Salvador or Puerto Rico? A categorical imperative is a mandate, a specific statement calling for fulfilling the duty of universal solidarity. This duty at present means on a collective level fighting for independence and national liberation for the world’s peoples.

Specifically in Our America it means supporting all peoples’ struggles against imperialism, colonialism and neocolonialism. Or, to continue in the line of thought of the peerless Cuban liberator, it consists of unceasingly fighting with every means at our disposal for the first and the second independence of all our peoples, perennial victims of imperialism’s domination and exploitation.

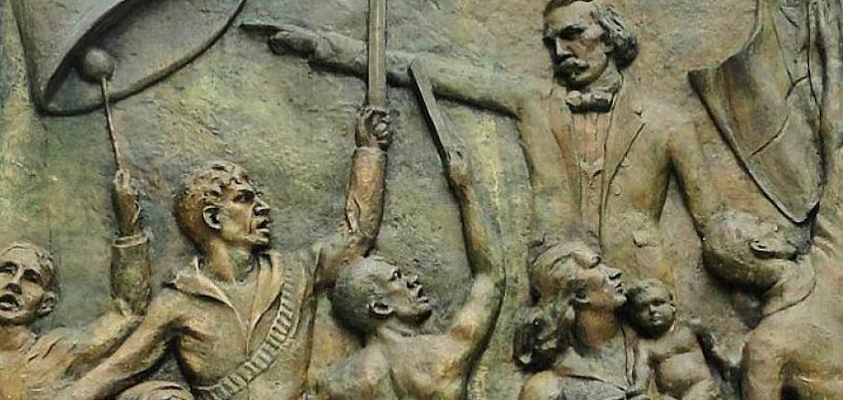

The history of Our America is singularly rich in terms of its liberation struggles. Fortunately, the new generation of Latin American historians and sociologists has taken on the job of retrieving these social struggles from the buried past where they have been assigned by official versions of history molded to the ideas of Latin America’s ruling classes. The struggles against oppression, from the uprising of the original Indian populations to those of the black slaves, from Tupac Amaru to Macandal, are glorious chapters in our peoples’ histories. The popular masses, the workers, these “historyless” peoples, are now in the forefront of current historical processes. We can view in this context those who took up the cause of these people, those who fought against oppression and plunder. We can put into their correct perspective events such as the 19th century Haitian Revolution and the 20th-century Cuban Revolution, the recent Sandinista Revolution and the glorious struggle being waged by the Salvadoran people right now. Our youth can identify with such men such as Toussaint L’Ouverture, Simon Bolívar, Ramón Emeterio Betances, Eugenio Maria de Hostos, Jose Martí, Augusto César Sandino, Augusto Farabundo Martí, Julio Antonio Bella, Pedro Albizu Campos, Ernesto Guevara, Salvador Allende, in short, with all those who embodied in word and deed, the hopes and desires of the peoples of Our America—without excluding, of course, all those anonymous heroes who daily are resisting and fighting, everywhere on every battlefront, attempts to deny our popular sector’s inalienable right to a decent life within their societies.

The concept of national liberation requires an exhaustive and thorough study which we cannot provide in his brief paper. But if we had to define its main outlines we could list the following: a) the struggle for national independence; b) the struggle against other subtle, and not so subtle, forms of domination that continue even after national independence has been won; c) the struggle for economic independence, that is, the struggle to recover for the use and enjoyment of the nation and all those means of production remaining in private hands; d) the socialization of these means of production and the process of building socialism. All these steps should take place for the full development of the national liberation process which, as can be seen, must culminate with socialism.

If we analyze in detail the ups and downs of these processes we can see that they have hardly followed a linear path; rather each process itself has been marked by advances and reverses. One thing is clear, nonetheless. The people’s struggle for liberation can be temporarily held back; it can even be contained for relatively long periods by the use of systematic repression against the popular sectors, but it can never be totally destroyed. As has been amply demonstrated in countries of the southern cone and Central America, fascist methods are used when the system of imperialist domination is threatened.

We will now proceed to examine more thoroughly each of the aspects of the national liberation struggle listed above.

In the first place, it is clear that for a people to exercise their sovereignty they must have national independence. Since Jean Bodin defined the concept of sovereignty in the 16th century, this has meant the exercise of supreme authority within a specific territory. For this concept to be not just a legal, but a real one, the people must be the basic source of that sovereignty. Therefore, colonialism, by placing the source of power in the hands of another country, is the denial of the principle of sovereignty. National independence, therefore, is the peoples’ basic freedom because it grants them the power to exercise sovereignty over a specific territory. The fact that this sovereignty can be infringed upon, even after achieving national independence, is common knowledge. But this is precisely why the peoples’ national independence struggle must be a frontal attack on imperialism, mortal enemy of the liberation of the world’s peoples. Those who do not perceive that imperialism is a system of global domination; who do not realize that this system, as Lenin so rightly affirmed, is the highest stage of capitalism in its monopoly stage; who do not understand that the socialist countries have not participated in the plunder of the natural and human resources of the peoples who have been and still are the victims of colonialism and neocolonialism, but rather that the socialist countries have aided in their struggle against underdevelopment, are seriously mistaken in their historical outlook, as Fidel Castro has pointed out on many occasions. The national independence struggles of the peoples of Our America have simultaneously been anti-imperialist struggles from Tupac Amaru up through our times.

But national independence is just a milestone — a very important one — in the national liberation process. Once independence has been attained, then the problem arises of the dependent relations which refuse to die and continue to be reproduced under the new sovereign status. These dependent relations have deep economic, social, political and cultural roots. When countries attain their independence under the system of dependent capitalism — as has usually been the case — their hard-won independence seems virtually annulled given the stubborn factors tending to perpetuate uneven development and economic backwardness. As shown by the unsuccessful efforts to create a new international economic order, and the failure of the overblown North-South dialogue, the capitalist countries are not willing to give up their privileges and prerogatives they derive from unequal exchange between raw materials and manufactured goods. Attempts by raw material exporting countries to excercise sovereignty over these resources have encountered the open hostility of the importing countries. Despite this, it should not be forgotten that the demand for full exercise of the people’s sovereignty over their natural resources was raised by General Lázaro Cárdenas in Mexico and with his actions an irreversible process was set into motion, refuting the already discredited notion that our peoples are incapable of efficiently administering what by right is theirs.

Therefore, if there is no struggle for economic independence, national independence runs the risk of becoming merely the nominal exercise of sovereignty. Martí warned us in the 19th century of the tiger stalking our peoples even after they have attained national independence. It is necessary to be on guard against this tiger because it always returns by night to endanger the gains of the peoples. Martí was referring, needless to say, to the imperialism he knew so well, having lived in its entrails; thus he warned the peoples of Our America to resolutely struggle for that second independence which could only be won through a frontal attack against that “violent and brutal north which despises us.” Economic independence is a requisite for the real exercise of sovereignty; it is the people’s’ demand that they not be subject to the conditions imposed by transnational corporations, that their natural and human resources not be subservient to international industrial and financial capital, and that their territories not bristle with army and naval bases which foreclose the peoples’ sovereignty. In reference to this last point, we have the situation of the base at Guantanamo in Cuba, which continues to be a flagrant insult to our peoples.

From what has been said up to here we can see that the peoples’ struggle for the full exercise of their sovereignty must lead to the socialization of the principal means of production and a process towards socialism. This, of course, is no easy task. The resounding victories of the peoples of Cuba, Vietnam, and Angola — to mention only three examples — have provided a revanchist dynamic in Western ruling circles, a dynamic which has as its current political expression the coming to power of the Reagan administration.

In the current political situation, national independence and sovereignty of all the world’s peoples are endangered by the rise to power of the most recalcitrant and militaristic sector of the U.S. ruling class. In the Caribbean, Nicaragua and Grenada are daily facing the threats of intervention that have long been part of our peoples’ history under U.S. hegemony. Revolutionary Cuba is facing new aggressions from U.S. Imperialism. The only thing that can stop this power, the only force able to counteract its mad ambition for world domination is the existence of the socialist world, which has stood up to the arrogance which has characterized the imperial republic of the United States since its very inception.

Imperialism, as a worldwide system of domination, can live with national independence only if this independence is not used to challenge capitalist relations of production. The process towards economic independence is already an irritant in imperialism’s relations with independent countries, but there is always the possibility of creating new trade and industrial relations which turn into a mockery, or make inoperable the processes of socialization of social wealth. Capitalism, however, cannot live with the transition toward socialism which endangers its domination over the lives and wealth of “Third World” social formations. Not even the creation of structures like people’s power is acceptable to the ruling classes. They will not permit naughty children: the empire demands total submission, and if this is not forthcoming, it means war: a war which at the beginning takes the form of economic aggression but with the broad range of resources at its disposal can even go as far as chemical and biological warfare.

It is in this context that the struggle is being waged by the peoples for their sovereignty, i.e. for complete control over their national territories, including the subsoil and surrounding territorial waters, the fauna and flora, water resources, etc. This sovereignty cannot be fully exercised unless real power is held by the social class which produces social wealth, the class that along with the natural resources which are mankind’s heritage, represents the most important of the material productive forces: the working class.

It is precisely the working class, together with the peasants and the other popular sectors, which is called upon to play the historical role as protagonist of the struggle for national liberation and socialism which is the only path to win our people’s sovereignty.

When our first liberators fought against the disintegrating Spanish empire, their main concern was to end the horrible system of oppression that prevented, by its retarding action, the full moral and material development of our peoples. In the Antilles, for example, this great struggle was waged not only to attain national independence, but also to end black slavery. It was in this sense that the three great 19th-century Antillean figures — Hostos, Betances, and Martí — were not only revolutionaries who fought to break colonial ties with Spain, but also they couldn’t imagine for a moment that black slavery would be tolerated in the new republics. They fought for a political revolution as well as a social one. By this time Karl Marx had already written the first volume of Capital and had founded the International Workingmen’s Association. But socialism, as a historic vision, valid for Europe of this period, did not appear, nor could appear, in the political outlook of these great Antillean revolutionaries.

The struggle to liberate the Antilles began at the same time as imperialism’s mad scramble for colonies in which over two-thirds of the world’s population fell victim to capitalist expansion. Marx, who died in 1883, had already started to analyze this process but a fuller description would have to wait for V.I. Lenin in his work, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. Although Martí, even before Lenin, had given a brilliant description of this phenomenon he did not hesitate to call imperialism, unquestionably it was Lenin who based his analysis on historical materialism and delineated the historical role of the national liberation movements in the struggle against imperialism. Thus the basis was established for the anticolonial and anti-imperialist struggles to be connected to the struggle for national liberation and socialism. What better example of this than the life and work of the great revolutionary and people’s leader named Ho Chi Minh!

Therefore the Latin American revolutionary tradition, to the extent it has been consistently anti-imperialists, goes perfectly hand in hand with the current struggle of the peoples to exercise their sovereignty and for their national liberation. On the centennial of the Grito de Yara, Fidel Castro stated, referring to the 19th-century revolutionaries, that if they were alive today they would be like us, and if we had lied then we would have been like them. We must meet this challenge if we are determined to confront the most powerful enemy in mankind’s history.

One last thought. The national liberation of the peoples of what Martí called Our America can never be complete until all the countries Bolivar included in his liberating vision have attained their independence. I come from a U.S. colony which is one of the strongest links in its chain of domination in the Caribbean. None other than Major Ernesto Guevara affirmed that one’s anti-imperialism could be measured by the extent of one’s solidarity with Puerto Rico. For more than a century our people have been waging a struggle for independence and national liberation. Different historic reasons have made it impossible up to now to write this last verse of Bolivar’s poem. But as long as Puerto Rico has not attained its full sovereignty and independence, the sovereignty of all the peoples of Our America is endangered. Therefore, we affirm in conclusion, that Puerto Rico’s national liberation is a categorical imperative demanding the militant solidarity of all the world’s peoples.

Manuel Maldonado-Denis, “”National Liberation: Categorical Imperative for the Peoples of Our America,” Tricontinental 82 (1982), 8-15 .

https://blackagendareport.com/essay-nat ... denis-1982

******

Reopening the Veins of Latin America

Posted on January 6, 2026 by Nick Corbishle

y

Latin America is the region of open veins. Everything, from the discovery

until our times, has always been transmuted into European— or later United

States— capital, and as such has accumulated in distant centers of power.

Everything: the soil, its fruits and its mineral-rich depths, the people and their

capacity to work and to consume, natural resources and human resources.

Production methods and class structure have been successively determined

from outside for each area by meshing it into the universal gearbox of

capitalism…

For those who see history as a competition, Latin America’s backwardness

and poverty are merely the result of its failure. We lost; others won. But the

winners happen to have won thanks to our losing: the history of Latin

America’s underdevelopment is, as someone has said, an integral part of the

history of world capitalism’s development. Our defeat was always implicit in

the victory of others; our wealth has always generated our poverty by

nourishing the prosperity of others — the empires and their native overseers.

Eduardo Galeano, The Open Veins of Latin America

These two paragraphs, taken from page two of Galeano’s 1971 classic tome, pretty much sum up the basic argument of The Open Veins of Latin America: what should have been a source of strength for the region — its vast wealth of natural, mineral and energy resources — became its greatest curse, attracting the unending attentions of foreign powers.

Since Columbus’ first voyage over 500 years ago, Latin America has always served the economic interests of an imperial metropole — first Madrid and Lisbon, then Paris and London, and finally Washington. By contrast, the 13 colonies to the north had been blessed with “no gold or silver, no Indian civilizations with dense concentrations of people already organized for work, no fabulously fertile tropical soil on the coastal fringe. It was an area where both nature and history had been miserly: both metals and the slave labor to wrest it from the ground were missing. These colonists were lucky.” (p.133).

It is a compelling argument, though one that, as Galeano himself would later admit*, overlooked other fundamental factors such as weak institutions, government corruption and the unwillingness of the local comprador elite to share in the spoils of entreprise. Nonetheless, the book would go on to become the Bible of the Latin American left, so much so that it was banned in many of Latin America’s military dictatorships, including Galeano’s native Uruguay.

In April 2009, during the Fifth Summit of the Americas held in Port of Spain, Venezuela’s former President Hugo Chávez famously gave President Barack Obama a copy of the book. Obama had only been president for about 100 days and Chávez may have hoped that Nobel Peace Prize winner Obama had actually sincerely meant what he had said about hope and change, and ending US wars.

Presumably, Obama didn’t even bother to read the book. If he had, he may not have issued a presidential order in 2015 declaring the situation in Venezuela an “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States”. That declaration opened the way for endless rounds of crippling sanctions against Venezuela’s economy and people.

As Vijay Prashad delicately put it an an interview with Katie Halper, the United States, regardless of who is in power, “is a piece of shit when it comes to Latin America.”

However, in the past two and a half decades, something else has happened: China went global, becoming a near-peer economic rival to the US. At the turn of the century, as Washington was shifting the lion’s share of its attention and resources away from its immediate neighbourhood to the Middle East, where it squandered trillions spreading mayhem and death, China began snapping up Latin American resources.

This doesn’t mean that US-backed coups were not attempted during this period, including against Venezuela in 2002 and 2019 (both unsuccessful) and Honduras in 2009 and Bolivia in 2019 (both successful), but rather that for a brief while Washington’s leash was loosened a little (h/t Valiant Johnson).

In the first decade governments across Latin America, from Brazil to Venezuela, to Ecuador and Argentina, took a leftward turn and began working together across various fora. They also began working with China. Unlike the US, Beijing generally does not try to dictate how its trading partners should behave and what sorts of rules, norms, principles and ideology they should adhere to.

Even governments in thrall to the US, such as Milei’s in Argentina, have reluctantly embraced China’s way of doing business. Chinese trade with Latin America grew over 40-fold between 2000 and 2024, from $12 billion to $515 billion.

Now, however, as the US retrenches from some of its commitments further afield (or at least tries/pretends to), the Trump administration is looking for peoples, resources and markets closer to home to respectively exploit, plunder and crowbar open. Sadly, it seems that a new chapter in Latin America’s long history of open veins is about to be written, and unfortunately Galeano is no longer around to do it, having passed away in 2015.

Dark Shades of the Past

In the wee hours of January 3, the US carried out its first direct military intervention in Latin America since its 1989 invasion of Panama to depose the then-military ruler, Manuel Noriega. That attack resulted in the deaths of at least 3,000 people, mostly civilians. Current reports suggest that around 100 people, including 32 Cuban soldiers that were protecting President Nicolás Maduro, died in the US attacks against Venezuela in the early hours of January 3.

The attack has drawn inevitable parallels with the “capture” of Noriega as well as the Honduran army’s kidnapping and removal of President Manuel Zelaya to Costa Rica in 2009. It also bears similarities with the US’ kidnapping of the Mexican drug cartel leader Mayo Zambada in 2024. Like Zambada, Maduro may have been kidnapped by US forces as a result of insider betrayal, but there is as yet no definitive proof of this.

As Ambassador Chas Freeman said in an interview with the Neutrality Studies podcast, Maduro appears to have fallen victim to his own complacency regarding Trump’s intentions:

Nicolás Maduro discounted it too much. He seemed to believe that Trump would not be serious. The first thing to note is that the operation itself was very skilfully managed. The second is that it is entirely illegal, indecent, an atrocity really. And I think it put to an end three centuries of trying to develop a rule of law internationally.

Lawrence Wilkerson put it even better on the Dialogue Works podcast, saying that Trump’s assault on Venezuela has not only put an end to international law, it has replaced it with chaos.

The Trump administration claims to have taken full control of Venezuela despite having no troops on the ground, apart from presumably a few special forces. The Chavista government and political system remains very much in tact despite the US’ extraordinary rendition of its president.

As such, the Trump administration’s claims that the US is now in full control of Venezuelan oil are almost certainly premature. What’s more, the US has not nearly enough troops in the region to carry out a full scale invasion of Venezuela. Even if it did, it would risk suffering a fate similar, or even worse, than Vietnam, as we warned a few months ago.

The question many are now asking is how long can this new, highly precarious situation hold together, especially with Trump threatening to launch a second wave of attacks should the new government fail to comply with US demands. The answer is nobody knows.

One thing that is known is that the Chavista government is nothing if not resilient. It has faced just about every possible form of attack from the US over the past two and a half decades, with the exception of a full-scale invasion. Yet somehow, like Cuba, it has managed to survive. In other words, it has deep wells of resolve and support. But will they hold if the US intensifies its shakedown of the government and tightens its chokehold on the economy?

In her first communication as new acting president of Venezuela, Delcy Rodríguez struck a combative stance, accusing Israel of involvement in the attack and declaring that Venezuela will never be the colony of an empire again. She also demanded the release of President Maduro. In her second address, however, she struck a much more conciliatory tone:

“Venezuela reaffirms its commitment to peace and peaceful coexistence. Our country aspires to live without external threats, in an environment of respect and international cooperation. We believe that global peace is built by first guaranteeing peace within each nation,” according to a post Rodríguez wrote in Instagram on Sunday.

“We invite the US government to collaborate with us on an agenda of cooperation oriented towards shared development within the framework of international law to strengthen lasting community coexistence,” read the post.

“President Donald Trump, our peoples and our region deserve peace and dialogue, not war. This has always been President Nicolás Maduro’s message, and it is the message of all of Venezuela right now. This is the Venezuela I believe in and have dedicated my life to. I dream of a Venezuela where all good Venezuelans can come together. Venezuela has the right to peace, development, sovereignty and a future.”

Rumours of Betrayal

Some prominent Chavistas, including Eva Golinger, are clearly not happy about Rodriguez’s acquiescence, with some even using the word “betrayal” to describe her actions.

When it comes to betrayal by presidential successors, Latin America has a rich, storied history, as reader vao noted in yesterday’s comments:

The handover from Rafael Correa to Lenin Moreno in Ecuador constitutes a sobering precedent: from a leftist government that implemented quite a number of reforms favouring the working class, sovereignty in the exploitation of resources, and autonomy from the USA to one doing a 180-turn (Baerbock-360) that privatized everything, abolished social reforms, exited ALBA, accepted the yoke of the IMF, and started a steady cooperation with the USA. The former base of Correa protested heavily, and was crushed.

Moreno had been vice-president of Correa, and was member of the same party — just like Delcy Rodriguez wrt. Nicolas Maduro.

Rodríguez’s promotion also brings to mind the US-approved appointment of Dina Boluarte, Peru’s then-vice president, as president in 2022, following the removal, arrest and imprisonment of Pedro Castillo, Peru’s first ever indigenous president. Broadly reviled from the get-go, Boluarte would go on to become one of the world’s most unpopular leaders, reaching a disapproval rating of 94% before herself being impeached by Peru’s Congress late last year.

A Loaded Gun to the Head

For the moment, I am unaware of any conclusive evidence that Rodríguez betrayed Maduro. Things are moving extremely fast, good information is scarce, even in the Spanish-speaking press, and the dust has not even settled from the US’ January 3 attack.

Also, in her defence, what else could she have done?

She essentially has a loaded gun at her head. Trump himself, in full New York mobster mode, has said she could “pay a very big price, probably bigger than Maduro”, if she doesn’t comply with US demands, including giving US corporations “total access” to “the oil and other things”. At the same time, the US’ naval blockade is beginning to asphyxiate the Venezuelan economy.

Delcy and her brother, Jorge, the president of Venezuela’s National Assembly, are arguably the most powerful duo in Venezuela. But they also know from first-hand experience just how high the stakes can go in US-led power struggles: their own father, Jorge Antonio Rodríguez, a student leader and left-wing politician, was tortured to death by Venezuela’s US-controlled security forces in 1976 at the age of 34.

Two things we know for sure: Nobel War Prize winner María Corina Machado has been left out of the picture by both Trump and (a presumably reluctant) Rubio, at least for the foreseeable future. Trump said that while Machado was a “very nice woman,” she “doesn’t have the support within or the respect within the country” to lead Venezuela.

As we have been warning over the past month or so, there is no way the Venezuelan people, including many opposition supporters, would accept a Machado-led government, especially after Trump’s announcement in December that Venezuela’s oil effectively belongs to the US. There are apparently other reasons, however, including Trump’s wounded ego…

In abandoning Machado, Edmundo González and most other members of Venezuela’s rent-an-opposition, the Trump administration has infuriated elements of Spain’s Conservative Right, including José María Aznar’s FAES foundation, which has invested lots of political and financial capital propping them up. And that in turn appears to be causing a split in Spain’s right-wing bloc. And that’s at least one positive to take from all this.

The second thing we know for sure is that Latin America now faces a new wave of US gangsterism and resource plunder — one that has even less regard for things like national sovereignty, international law and human rights. While this new wave may be led and personified by Trump, behind him is the full weight of the US energy and military complexes as well as the Tech bro billionaires, who are looking not only for resources to plunder but also new freedom cities to seed, just like Prospera Inc. in Honduras.

The attack on Venezuela was the first real manifestation of the so-called Trump corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. Said corollary, as outlined in the recently published National Security Strategy document, asserts Washington’s right to “restore American pre-eminence in the Western Hemisphere,” and to deny “non-Hemispheric competitors” — primarily, China — “the ability to position forces or other threatening capabilities, or to own or control strategically vital assets.”

Those vital assets apparently include Venezuela’s vast oil reserves, which Trump cannot stop talking about. However, as Yves pointed out in her post yesterday, “wringing more production out of Venezuela’s oil fields would require a long period of investment before any real payoff took place.” And that investment is likely to run into the tens of billions of dollars.

Trump has also stated that while his government would open Venezuelan crude only for US companies, he expected to keep selling crude to China, which currently consumes most of Venezuela’s small (but recovering) output.

A Treasure Trove of Strategic Minerals

But oil isn’t the only strategic resource lying under Venezuelan soil. The country is also home to the fourth largest gold reserves on the planet and eighth largest natural gas reserves, as well as a treasure trove of critical minerals (bauxite, iron ore, copper, zinc, nickel and even rare earth materials). However, as Investor News points out, these critical mineral riches remain largely theoretical – geological possibilities rather than proven, bankable reserves:

Yet despite this vast resource wealth, commercial extraction is negligible. Minerals such as coal, lead, zinc, copper, nickel, and gold each account for less than 1% of Venezuela’s output (Ebsco.com), and there are no major foreign mining projects on the ground…

Due to a chronic lack of infrastructure, investor-friendly regulations and up-to-date exploration data, commercial extraction is negligible, notes the Investor News piece. Minerals such as coal, lead, zinc, copper, nickel, and gold each account for less than 1% of Venezuela’s output, and there are no major foreign mining projects on the ground. At least not yet.

However, Wall Street funds are apparently already eying opportunities in the country, reports the Wall Street Journal. The kidnapping of Maduro has apparently sparked renewed interest in unlocking Venezuela’s abundant natural resources:

Some on Wall Street are already considering possible investment opportunities in Venezuela following the capture of Nicolás Maduro, according to Charles Myers, chairman of consulting firm Signum Global Advisors and a former head of investment advisory firm Evercore.

Myers said in an interview he is planning a trip to Venezuela with officials from top hedge funds and asset managers to determine whether there are investment prospects in the country under new leadership. The trip will feature about 20 officials from the finance, energy and defense sectors, among others, Myers said. The tentative plan is for the group to travel to Venezuela in March and meet with the new government including the new president, finance minister, energy minister, economy minister, head of the central bank and the Caracas stock exchange.

And lest we forget, the Trump corollary is as much about trying to shut out the US’ strategic rivals — namely China, Russia and Iran — from strategic resources on the American continent as it is about the US getting its own dirty, blooded hands on them. And as we reported some time ago, China had begun to invest a lot in Venezuela’s oil sector, including in local refineries.

Put simply, the spice must not be allowed to flow to US rivals. Here we have the US ambassador to the UN saying exactly that yesterday:

This may sound vaguely familiar to long-standing NC readers, since a similar message was sent three years ago by the former SOUTHCOM commander, general Laura Richardson, in her address to the Atlantic Council.

In the speech Richardson relayed how Washington, together with US Southern Command, is actively negotiating the sale of lithium in the lithium triangle to US companies through its web of embassies, with the goal of “box[ing] out” our adversaries — i.e. China, Russia and Iran.

Which begged the question: what would happen if the US was unable to “box out” Russia and China, especially given the explosion of Chinese trade and investment in the region? Richardson answered as follows (emphasis my own): “in some cases our adversaries have a leg up. It requires us to be pretty innovative, pretty aggressive and responsive to what is happening.”

As we noted at the time, the US was essentially rejigging its Monroe Doctrine for a new age — an age in which it was rapidly losing economic influence, even in its own “backyard” — in order to apply it to China and Russia. At more or less the same time, the Biden administration signed, to minimal fanfare, a “minerals security partnership” (MSP) with some of its strategic partners, including the European Union, Canada, Australia, Japan, the Republic of Korea and the UK.

In a press statement, the US Department of State said:

“The goal of the MSP is to ensure that critical minerals are produced, processed, and recycled in a manner that supports the ability of countries to realise the full economic development benefit of their geological endowments.”

As NC reader Sardonia put it sardonically, this is “surely some of the most polite language ever heard from someone holding a gun to someone else’s head as they demand the contents of their victims’ purse.” The US describes the partnership as a coalition of countries that are committed to “responsible critical mineral supply chains to support economic prosperity and climate objectives.” Reuters offered a more fitting description: a “metallic NATO.”

The Trump administration is merely taking this approach to a whole new level, and doing so in the crassest, most dangerous possible way. After kidnapping Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, just two days ago, the Trump administration will presumably be returning its attentions to the Panama Canal and Greenland. Trump has already made direct threats against the governments of Cuba, which depends heavily on Venezuela’s commandeered oil, Colombia and Mexico.

Senator Lindsay Graham is hardly able to contain his glee as Trump tells reporters that “Cuba is ready to fall”, and that there are “a lot of great Cuban Americans that will be happy about this”.

Here is Rubio, again, explaining that while the US (apparently) doesn’t need Venezuelan oil, China, Russia and Iran certainly shouldn’t be getting their hands on it.

On Sunday, Trump told reporters on Air Force One:

“Colombia is governed by a sick man, who likes to make cocaine and sell it to the United States, but he is not going to continue for much longer, let me tell you.”

When asked by a reporter if Washington is considering “an operation like the one in Venezuela,” Trump did not rule it out: “It sounds good to me.”

Trump has also threatened, once again, to attack Mexico in recent days, prompting a stinging rebuke from President Claudia Sheinbaum:

We categorically reject intervention in the internal affairs of other countries. The history of Latin America is clear and compelling: Intervention has never brought democracy, has never generated well-being or lasting stability.

Five Latin American states (Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, Uruguay and Chile) issued a joint statement with Spain’s Pedro Sánchez government rejecting the US’ unilateral military operations in Venezuela, describing them as violations of international law and warning of the risk to regional peace.

This is a tiny fraction of the total number of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (33). As always, Latin America is sharply divided between pro-US national governments and more independent-minded ones. However, populist right-wing parties are having more success at the ballot box, in part because of Trump’s threats of dire consequences if voters support other parties, as we have already seen in Argentina and Honduras.*

It remains to be seen how the US’ naked aggression in Venezuela will play out among voters in Colombia and Brazil, where elections will be held this year. Meanwhile, as Spain’s El Diario recently reported, while the US has escalated its war of aggression against Venezuela, the White House has been discreetly signing security agreements with other countries that will allow it to deploy soldiers in Latin America and the Caribbean:

In recent weeks, the United States has struck military deals with Trinidad and Tobago, Paraguay, Ecuador, and Peru, as the Trump administration announced blockades of sanctioned oil tankers, ordered the seizure of ships, and launched the airstrikes that have killed more than 100 people in the Caribbean and Pacific. In addition, Washington has opened a new phase in its campaign against Maduro with CIA attacks inside the country.

The agreements range from access to airports, as in the case of Trinidad and Tobago, to the temporary deployment of U.S. troops in joint operations against “narco-terrorists,” as in Paraguay. They are being signed under the banner of the so-called “war on drugs,” the same justification that Washington uses for its offensive against Venezuela, although White House officials and Trump himself have said that toppling dictator Nicolás Maduro and seizing the country’s gigantic energy reserves are also among the objectives.

But even that narrative is now being discarded — at least for Venezuela. Now that Maduro is in a New York prison awaiting trial, the US Justice Department has quietly dropped its claim that Venezuela’s “Cartel de los Soles” is an actual group.

As we warned from the very beginning of the US’ deployment of troops in the Caribbean, the US’ rapidly escalating war on the drug cartels is nothing but a handy pretext for another wave of resource grabs in a region the US has always seen as its own backyard:

This forever war has about as much to do with combatting the narcotics trade as the forever wars in Iraq, Syria, Libya and Afghanistan had to do with combatting Islamist terrorism.

After all, the US is arguably the largest enabler of drug trafficking organisations on the planet while it wages a Global War on Drugs, just as it has been arguably the largest supporter of Islamist terrorist organisations while waging a Global War on Terror. Both types of organisations have proven to be useful allies in the pursuance of US imperial ambitions (e.g. the Colombian and Mexican cartels during Nicaragua’s Contra insurgency in the 1980s, or the Al Qaeda offshoots in Syria) while also serving as handy pretexts for military intervention.

In the following clip, Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater, sums up the (not exactly) new brand of imperialist thinking underpinning the Trump administration’s naked expansionist goals: if the natives can’t manage their own resources, we’ll just have to do it for them. Then, after plundering the mineral resources of the region’s countries, the US can turn around and blame them for being poor.

But just because Washington covets Latin America’s resources does not mean it will actually get them. As Yves documented yesterday, it will take years of investment and (at least) tens of billions of dollars for Venezuelan oil to be even close to ready to be exploited in serious volumes. Few companies are likely to be willing to part with that sort of cash, especially in light of the fact that Washington does not control Venezuelan territory, even at a figurative level.

However, Trump just announced that it will be the US government that will be doing the spending (h/t JD). After all, socialising private sector losses — and now, large scale investments — while privatising profits is now the model of US governance. Exxon Mobil, for example is currently under investigation in the US Senate over allegations that US taxpayers are unknowingly subsidizing the oil giant’s lucrative operations in neighbouring Guyana.

As the Guyana Business Journal reported in September, ExxonMobil is essentially claiming US tax credits for taxes on oil revenues that the Guyana government itself pays on the company’s behalf, rather than taxes the company actually pays itself. Keep in mind that Exxon is (presumably) one of the oil companies that Marco Rubio claims will be helping to rebuild Venezuela’s oil sector for the benefit of the Venezuelan people.

The US will presumably fail in its latest attempt to take over Latin America, lock, stock and, ahem, barrel, due in large to the Trump administration’s abject inability to plan for complex situations — it can’t even run its own government departments let alone others’. However, it is perfectly capable of sowing a vast trail of devastation and bloodshed in its wake, just as US governments have been doing in the region for the best part of the past two centuries.

* In 2014, Galeano partially disowned “Open Veins…“, saying in a speech in Brasilia that he would never read [the book] again, because if he did, he would faint.” According to Galeano, the book was written in a tedious style (and I have to admit, it’s not easy) and using the doctrinal tone of the traditional left. He added that in those early days of his career, he didn’t know enough about politics and economics to write a book of such scope.

From Revista Factum (machine translated):

He realizes that the dependency paradigm, with its rejection of Western capitalism, which underpinned his book had important shortcomings and overlooked other fundamental problems. Galeano underestimated the impact of weak institutions – anticipated by Bolívar in the early 19th century – and internal political and economic problems, such as government corruption and the unwillingness of the ruling classes to contribute to the development of more democratic and egalitarian societies, as Marx himself would argue when writing about the countries of the South.

For interested readers, here’s a link to a full copy (in English) of The Open Veins of Latin America, which includes a foreword by Isabel Allende.

https://library.uniteddiversity.coop/Mo ... merica.pdf

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2026/01 ... erica.html