THE MAS WINS THE ELECTIONS IN BOLIVIA: EVOLUTION AND RECOUNTING OF A POLITICAL MILESTONE

19 Oct 2020 , 8:29 am .

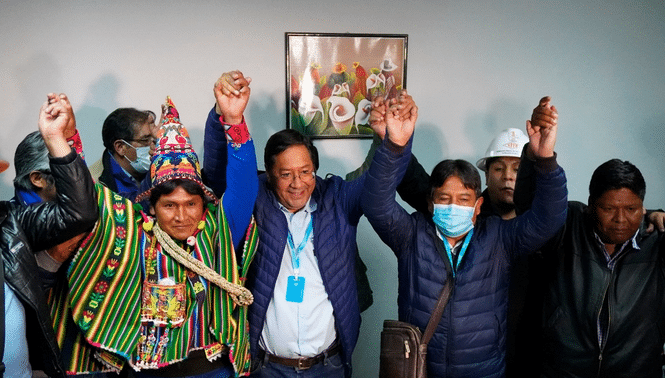

Luis Arce and David Choquehuanca, president and vice president-elect of Bolivia this October 18 (Photo: Ueslei Marcelino / Reuters)

Bolivia rises with a new political milestone for itself and for the region, through the victory, until now certified by exit counts, of Luis Arce to the presidency of the Plurinational State.

This highly political event must be classified as emblematic due to its particularities and evolution.

FROM BUENOS AIRES TO COCHABAMBA, THEN TO PALACIO QUEMADO

An institutionally outraged Bolivia saw its powers dismember in the process of escalation and final consummation of the November 2019 coup d'état. With the military forced resignation of Evo Morales, his departure to Mexico and the consolidation of the coup, the days that followed were of blood and chaos.

This caused a wound in the political fabric of the Movement for Socialism (MAS), from the cascading disaster of its leaders before the coup and the political persecution that followed weeks later. All this meant an unprecedented moment of demoralization.

In unison with the rise of Jeanine Áñez, the economic elite and the people of Santa Cruz to the power structure, the dispersion of the MAS components and other social outposts that followed Morales occurred. With the forces that tried to repel and degrade the blow exhausted, the scene seemed of resignation and impossibility.

However, Evo Morales reappeared in exile in Argentina. His immediate task was the recomposition of the political forces beyond his figure and he dedicated himself to regroup and reorganize his support base: a difficult position for an overthrown president and in exile, approached by criticism and in a generalized picture of distress.

By December 2019, the MAS in Parliament engaged in the controversial but intelligent strategy of "living together" and maneuvering with the emerging institutions of the dictatorship, preserving the parliamentary spaces to pressure, from that instance, the permanence of the MAS as a force legal policy and promoting the electoral agenda.

Evo Morales met in Buenos Aires with factors from the Central Obrera Boliviana, mining sectors, indigenous people, peasants, coca growers and other grassroots forces, reuniting and reattaching perspectives for a common roadmap in the face of the new realities.

In January 2020, the MAS is raised in a unitary formula. Despite the discrepancies of the moment and the possibility that the political standard-bearer was David Choquehuanca, because of the same pressures that emerged after the disaster that Morales' displacement meant, the ousted president managed to amalgamate the social forces under his leadership and they accepted the leadership of Luis Arce in the formula.

The strategy seemed obvious. Arce came from conducting the best economic cycle in the contemporary history of Bolivia and was a highly accepted figure in sectors affected by Morales and beyond. However, Arce's figure would have been lazy on its own, without the support of the deep political fabric. Morales made sure to get the support Arce needed.

The rise of this new formula kept its paradoxes. One of them is that, after the coup, the figure of former vice president Álvaro García Linera, widely followed by the Latin American left and, in theory, Morales's successor, disappeared from the political radar.

Arce and Choquehuanca imposed a new momentum and immediately set about leading the internal opposition to Áñez, recomposing the political forces from below, in a synergy between indignation and the electoral roadmap, towards the rescue of the Palacio Quemado, traditional headquarters of the Bolivian presidency, taken over by the coup plotters.

The Bolivian people went to vote en masse for the MAS (Photo: Página / 12)

THE ESCALATION IN SOCIAL PRESSURE

The advent of the Covid-19 pandemic led to electoral delay. The de facto president Jeanine Áñez proceeded to build an artificial institutional framework tailored to her government, prolonging the electoral period.

His last electoral delay was that of the elections scheduled for September 6. Postponed until this Sunday, October 18, the president again tried another suspension, this time, unsuccessfully.

In this reversal, the social response was key , which reappeared with a level of cohesion that was not seen in the disaster of November 2019. The blockades called by the Central Obrera Boliviana (COB) and the Pact of Unity demanding respect for the date The elections resulted in the almost total paralysis of the country's main routes, lasted for more than 10 days and generated controversy both in the national public opinion and within the popular forces and the MAS.

The road blockade also allowed the COB to enter the scene against the de facto government, who to date had remained on the sidelines of street actions, limiting themselves to declarative confrontations and threats of mobilization. The COB has on its shoulders the burden, let us remember, of having contributed to the consummation of the November coup after demanding the resignation of Evo Morales hours after the same demand from the military high command.

The balance of the blockades represented a turning point that heralded a new advantage for the popular forces. The de facto government, the armed forces and fascist organizations could not dismantle the street actions, showing themselves vulnerable for the first time after the November coup. The coup government concentrated its entire argument against Evo Morales, declaring him a "terrorist" for organizing the mobilizations.

This put a new ingredient on the table: that of the power of social force simultaneously with a political campaign. Both are very powerful ingredients in mass agitation and moralization.

Under the coup plotters' own narrative, Evo Morales led a highly articulated and effective outraged mass force. At the same time, Arce was vigorously leading an electoral campaign, whose lapses extended by the decision of the coup leaders ended up wearing down his opponents and consolidating his own figure as a man of the masses. All this in an area of social conflict in an upward spiral, due to the worsening economy and the poor management of Áñez in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic and in governance in general (including the massacres of Sacaba and Senkata at the end of last year ).

In other words, the alignment of components took place that made a "perfect storm" with winds favorable to MAS.

Jeanine Áñez decided to withdraw her candidacy in September to try to favor a second electoral round with Carlos Mesa at the helm. Obvious sign that the electoral consolidation of the MAS and its social response were giving a great balance.

ELECTION DAY

Unquestionably, the institutions founded by Áñez and his team gave all the signs of preparing an electoral coup. With just one day before the elections and using legitimate complaints from the MAS about its methodology , they eliminate the quick vote count and the immediate publication of results. A last minute trap.

Instantly, the electoral observation of the Organization of American States (OAS) and the European Union (EU) present in Bolivia endorsed the controversial decision.

This meant that the country would have to wait a few days for an electoral result to be presented after the total counting of votes and minutes, that is, the perfect habitat for delaying the results, ideal for their fraudulent manipulation.

However, it is worth saying that the election was preceded by various polls that, although they gave Arce an advantage to win the first round, were not entirely conclusive in defining the election on October 18.

To win in the first round, Arce would have to reach more than 40% and have more than 10% advantage over Mesa, the favorite of the divided Bolivian opposition and political architect of the 2019 coup. Hence, the election seemed in doubt to be defined in first round, an ideal electoral scenario for the MAS.

But a fact that was not very outstanding in the projections ended up being devastating in fact. In most surveys, there were between 19% and 24% of respondents who were undecided, or did not respond. They were followers of the MAS, who in a context of persecution and harassment refused to reveal their political militancy for fear of reprisals.

This October 18 the election took place and the statistical milestone of the "hidden vote" took place, as has rarely been seen in Latin American electoral history. That percentage of undecided was clearly inclined in favor of Arce and defined his victory in the first round.

The wait became prolonged after the closing of tables this Sunday 18. The electoral authority was in charge of delaying the counting process, even announcing a stoppage in the early hours of the morning. The scene of confusion was aggravated by the non-publication of results in exit polls, which lasted for five hours after the closing of the tables until their public launch.

The moment seemed ideal for the development of an ongoing fraud, but it seems that the forcefulness of the result in votes dismembered this possibility.

The exit poll conducted by the anti-Masist media Unitel and the firm Ciesmori were the first to publish the exit exit favorable to Luis Arce, with 52.4%, followed by Carlos Mesa with 31.5%; Santa Cruz leader Fernando Camacho had barely 10%. Other exit polls have shown similar trends.

The magnitude of the figure infers that the discrepancy between the exit result, versus the final result of the count, cannot be so different to the point of changing the final result. Arce is elected in the first round.

In these instances, the backstage that generated the delay due to the preliminary results and the setback in the evident intentions of the de facto institution to consolidate its usurpation of power through electoral fraud are indecipherable. What does seem evident is that, if the presented result were different, the social reaction would have taken place in unpredictable ways, in the face of an increasingly sedimented power structure.

Although the official vote count continues and the result is in the process of being endorsed through official channels, Jeanine Añez proclaimed the victory of Arce and Choquehuanca in a reluctant tweet.

Another actor in the coup in Bolivia last year, the Secretary General of the OAS, Luis Almagro, also congratulated Arce and Choquehuanca for the results.

The political picture in Bolivia changes in circumstances in which it seemed unlikely to happen. Under conditions imposed by a de facto government, the MAS retakes political power through voting, after an intense and hard journey with Evo Morales in exile, but as the undisputed leader and coordinator.

The keys to the Bolivian deed lie in a social and political fabric that remained cohesive, which was rebuilt in record time, in a pragmatic and intelligent political strategy presented at all times and in an effective use of electoral agitation and the agenda of Street. Those are the perfect components for a major political onslaught and it has taken place right in the heart of South America.

https://misionverdad.com/globalist%C3%A ... %C3%ADtico

Google Translator

Glad to be wrong. Special congratulations to MAS, to bounce back like that after the debacle last year speaks of organization and commitment. The class war continues but this battles is a win. The bosses got nothing but force and I'm guessing that the military, rank&file in any case, would be less than reliable if push come to shove and this factor more than any other impelled their capitulation.

.

.