John Ross: The international and historical significance of the resolution on the history of the CPC

The following article was originally published in Chinese by Guancha.cn.In his latest article, which we are pleased to republish from Learning from China, John Ross provides a useful summary of the three key resolutions on party history adopted by the Communist Party of China in its century of struggle. Against this background, John further outlines how generations of Chinese communists, and especially Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping and Xi Jinping, have defended, applied, enriched and developed Marxism-Leninism and in so doing have not only immeasurably improved the lives of the Chinese people but also contributed significantly to the progress of humanity, especially to the liberation struggles of the countries and peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America.

The “Resolution on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century”, adopted by the Sixth Session of the 19th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in November 2021, is, rightly, regarded as in the first place an issue for China itself. As the Resolution notes in its first sentence: “Since its founding in 1921, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has remained true to its original aspiration and mission of seeking happiness for the Chinese people and rejuvenation for the Chinese nation.”

It is obviously correct to start with the position of China itself. But the second sentence of the Resolution starts by noting the connection of China’s national struggle with international developments – in particular in regard to socialism: “Staying committed to communist ideals and socialist convictions, it [the CPC] has united and led Chinese people of all ethnic groups in working tirelessly to achieve national independence and liberation.” Indeed, for reasons that will be analysed, this resolution on the history of the CPC is of very great international and historical importance for all countries as well as for China itself. Therefore, while in no way wishing to deflect from the correctly China focussed nature of discussion on the Resolution, it is also hoped here it may cast some light on the discussion if international aspects of the significance of the Resolution are also considered.

WHY ONLY THREE RESOLUTIONS ON THE HISTORY OF THE CPC?

As has been widely noted the CPC has only adopted three resolutions on its history during the century of its existence.

*The first was in April 1945, as World War II was ending with the successful defeat of German and Japanese fascism, and the CPC was preparing for the struggle which in 1949 led to the creation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This was the “Resolution of the CPC CC on Certain Historical Questions.”

*The second was in June 1981, to consolidate China’s policy of Reform and Opening Up which had been launched in 1978. This was the: “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China.”

*The third, in 2021, was just adopted by the Sixth Plenum.

Therefore, the question is obviously raised as to why were these three occasions considered so important that they were especially marked out by the adoption of such significant documents? The answer to that may be found within the new resolution itself and by considering the international implications of each situation when they were adopted.

NEW DEMOCRACY AND THE BEGINNING OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF SOCIALISM

The first resolution on the CPC’s history, as was noted at the recent Plenum, was adopted in the period of the “new democratic revolution” led by Mao Zedong. This period secured China’s national unity and independence after more than a century of foreign military occupations and eliminated the remnants of China’s feudalism. After 1949 Mao Zedong also led the beginning of the construction of socialism.

These were epoch making achievements for China. But they were also monumental in their global significance and in the development of socialism and Marxism. Mao Zedong led a process which had never before been achieved in human history – to make a socialist revolution in an underdeveloped semi-colonial country. The present Resolution of the Sixth Plenum refers to this in summary in the context of China: “The shift from attacking big cities to marching into the countryside was a decisive new starting point for the Chinese revolution… In the course of the revolutionary struggle, Chinese communists, with Comrade Mao Zedong as their chief representative, adapted the basic tenets of Marxism-Leninism to China’s specific realities and developed a theoretical synthesis of China’s unique experience which came from painstaking trials and great sacrifices. They blazed the right revolutionary path of encircling cities from the countryside.”

But these striking statements in the Resolution on China do not elaborate on the international significance of what Mao Zedong and the CPC achieved – the Resolution is, rightly, focussed on China. Marx and Engels had, of course, laid the foundations of Marxism. Lenin had been the first to show how socialists could take power in an imperialist country. But it was Mao Zedong, and the CPC, that showed how socialists could take power in a developing, semi-colonial, country. This established Mao Zedong, with Lenin, as the greatest Marxist thinker of the 20th century.

But to develop this strategy Mao Zedong had to solve innumerable other problems than a simple shift in the “geographic” basis of the struggle – from the cities to the countryside. It was necessary to identify the correct method for analysing a situation (philosophic works such as “On Contradiction” and “On Practice”), new strategic methods for struggle (“On Protracted War”), new conceptions on the precise approach to socialist revolution (“On the People’s Democratic Dictatorship”) and numerous other contributions to Marxism. As the present resolution put it such contributions: “established Mao Zedong Thought, which charted the correct course for securing victory in the new-democratic revolution.”

Regarding the international implications of this, naturally no other country could or should mechanically apply the same conclusions, and the CPC has never advocated this, but the method of analysis of Mao Zedong Thought was an immense universal contribution to humanity.

Furthermore, for a prolonged period after Mao Zedong and the CPC put forward these concepts, other socialist revolutions and national liberation struggles directly learned from them. The socialist revolutions in Vietnam, Laos and Cuba followed the strategy of “the countryside surrounds the cities”. So many national liberation struggles against colonialism followed this strategy that is impossible to list them all – Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Algeria, Angola will do for a few.

In summary, China’s revolution of 1949 was of course above all a decisive event in China’s own history. But it also had enormous international ramifications.

*Mao Zedong analysis became, with Leninism, the greatest contribution to socialist theory and Marxism since the epoch of Marx himself.

*An entirely new chapter of Marxism was created in showing how a developing country could achieve socialism – and the methods of struggle which achieved this influenced numerous other progressive struggles.

*An immense strengthening of world socialism took place as China, at that time accompanied by the USSR, embarked on the road of socialist construction

These achievements were literally epoch making. While China was always careful to insist on the precise nature of the situation in each country, other countries could and did learn from China in order to aid in understanding their own specific situation.

In summary, the first resolution of the CPC on its history, in 1945, “Resolution of the CPC CC on Certain Historical Questions,” was in the first place, a decision concerning China. But it also had major consequences regarding the international situation and socialism. The fact that in 1945 the Soviet Union, not China, was the most powerful socialist force in the world meant that at this time this resolution did not receive the enormous international attention it merited. But this did not in any way detract from its fundamental objective significance.

THE ROAD TO REFORM AND OPENING UP

After the establishment of the PRC in 1949 gigantic steps forward for the Chinese people were taken. Modern industrialisation began. The greatest improvement in the conditions of the largest number of people in human history, in a similar time frame, was achieved – as measured in increased life expectancy, education, health etc.

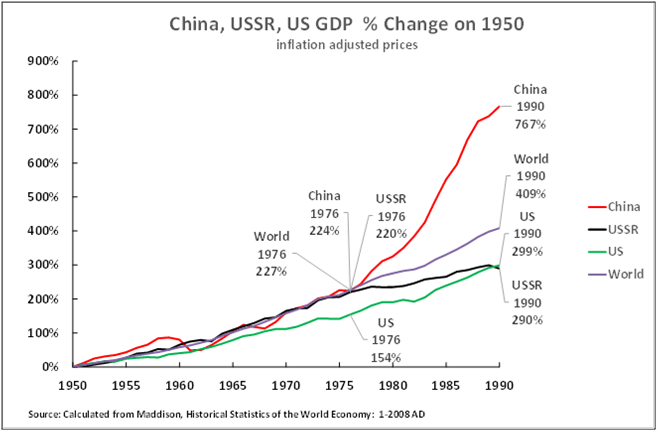

But at that time, despite these gigantic steps forward, China’s economic growth was only roughly in line with the world average. From 1950 until 1976, the year of Mao Zedong’s death, China’s GDP growth of 224% was essentially in line with the world average of 227%. China’s gigantic achievement was that this economic growth was overwhelming directed towards the improvement of the improvement of the lives of China’s people – and this was achieved. But while China made enormous steps forward in improving the conditions of its population in this period, and laid the basis for future economic development, it cannot be objectively claimed that it made overwhelming achievements in economic growth – due in part to mistakes in this period of which the Resolution notes in particular the errors of the “Great Leap Forward and the people’s commune movement” as well as the “catastrophic Cultural Revolution”.

This economic reality had a necessary consequence – including for China’s international situation. In 1949 China, due to a century of foreign invasions, had become almost the poorest country in the world in terms of per capita GDP. Therefore, if China’s GDP was only growing roughly in line with the world average, it would not escape from being a relatively poor country.

Furthermore, in the 1970s an overall crisis of the world economy, affecting both capitalist and socialist countries, began. In the capitalist countries, starting in 1971, the US launched an offensive against its competitors Japan and Germany – which until that point, since World War II, had been growing more rapidly than the US. The US imposed tariffs, insisted on radical increases in the exchange rates of Germany and Japan, and by these means succeeded in defeating its capitalist rivals. This was then followed by the US orchestrating a huge increase in oil prices – from which it, as a major oil producer, gained while Japan and Germany, which had no significant oil reserves, lost.

By these means by the end of the 1970s the US had comprehensively defeated its Japanese and German capitalist rivals and conclusively re-established dominance among capitalist countries – a position which it has not lost until today.

However, the US did not achieve this strengthened position, among capitalist countries, by accelerating its own economy – annual average US GDP growth, taking a 10-year moving average to remove the effect of short-term business cycles, almost halved from 4.3% in 1971 to 2.2% by 2020. Instead of accelerating its own economy, the US slowed its rivals – the 10-year moving average of annual GDP growth among advanced economies fell by an enormous 75%, from 5.1% to 1.3%, between 1971 and 2020. Primarily as a result of this annual average world economic growth, dominated during most of this period by capitalist countries, fell by more than half, from 5.2% to 2.4%, in the same period.

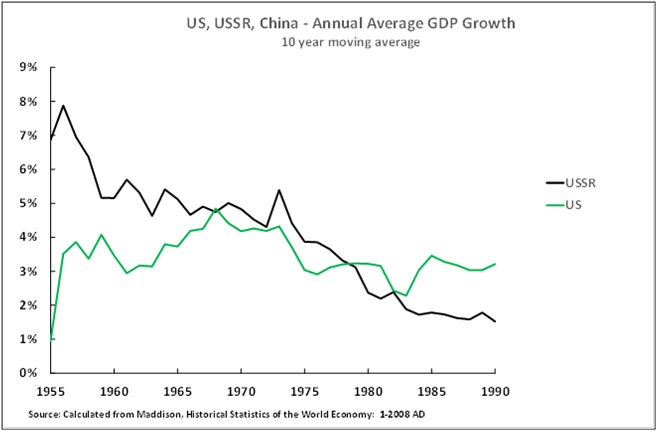

But simultaneously an economic crisis developed among socialist countries. By the late 1970s Soviet economic growth was slower than that of the USSR – see Figure 1. Despite the gigantic contribution to humanity of USSR, not only in the increase in the living standards of its population but in the defeat of German fascism and the destruction of the colonial Empires, this economic failure in turn led to a deep crisis in the USSR, creating the context for the disastrous policies of Gorbachev, and culminated finally in 1991 in the restoration of capitalism in the Soviet Union and the geopolitical catastrophe for Russia of the disintegration of the USSR.

But in contrast to the economic failure of the USSR, China from 1978 embarked on a policy which led to the most rapid economic growth in a major country in human history. By 1990, the last year of the USSR, China’s GDP had grown by 767% from 1950 – compared to 299% for the US, 290% for the USSR, and 409% for the world average (see Figure 2). Updating to the present, from 1978 to 2020 China’s economy grew by 3,914% compared to 231% for the US and a world average of 180%. In short, whereas by the mid-1970s the USSR’s economy was entering a crisis which resulted in its collapse, China was advancing to the most successful economic system seen in world history. It was this new economic policy and structure after 1978 which allowed China not only to avoid the economic failure of the USSR by the 1970s but to grow far more rapidly than any major capitalist economy.

The causes of this stupendous economic success of China after 1978 are set out in the new resolution of the Sixth Plenum: “China achieved the historic transformations from a highly centralized planned economy into a socialist market economy… and from a country that was largely isolated into one that is open to the outside world.” The domestic impact of this in China is so well known that it is unnecessary to deal with it in detail here – the fastest economic growth in a major country in world history, the fastest rise in living standards in any major country, more than 850 million people taken out of internationally defined poverty, the achievement of “moderate prosperity” by China’s domestic criteria, China being taken from almost the world’s poorest economy in terms of per capita GDP in 1949 to achieving, in the next three years, “high income” status by World Bank international standards.

To summarise, these achievements produced the greatest improvement in the living standards of the largest proportion of humanity in human history in any comparable time frame. This achievement, following on from the social miracle of the Mao Zedong period meant that, in the opening sentence of the Sixth Plenum resolution, the CPC confirmed its success in its: “original aspiration and mission of seeking happiness for the Chinese people and rejuvenation for the Chinese nation.”

But, in addition to its consequences for the Chinse people, what was the international significance of this achievement? This may be stated bluntly with full understanding of the significance of the words. It is often, correctly, stated in China that only socialism saved China from national humiliation. But while China embarked on its socialist revolution in 1949, and then Reform and Opening Up in 1978, for reasons of its national rejuvenation nevertheless this produced an epoch making international effect. Regarding Reform and Opening Up it may be stated bluntly that the economic policies embarked on by China under Reform and Opening Up, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping and the other leaders of the CPC, saved world socialism. This statement is not intended in the slightest to belittle the role of other countries which achieved socialism, and the achievements of which were decisive for their country. In the period after World War II other countries achieved socialist revolutions which were decisive for their own development, and which had a great international impact – notably Cuba and Vietnam. But, given the strength and aggression of US imperialism, which was fully demonstrated after the collapse of the Soviet Union in military attacks on Iraq, Libya and other countries, only the USSR and China had the strength to prevent US aggression against themselves and other countries. After the collapse of the USSR only China possessed that strength.

More than that, China’s stupendous economic success after 1978 destroyed the argument that socialism was an economically inefficient system – a myth which was created by the economic failure of the USSR by the 1970s. China achieved what every developing country dreamed of – to take its people from poverty and underdevelopment to prosperity in a single lifetime. China, rightly, never proposed to other countries to copy its “model”. But any progressive force with sense would study China’s success to understand what lessons could be applied to the situation of its own country.

The contrast between the economic failure of the USSR and China’s success was also totally clear. As Gennady Zyuganov, leader of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, noted in 2008 regarding China’s policy of Reform and Opening Up: “Had we learned from the success of China earlier, the Soviet Union would not have dissolved.”

THE CPC’S TRIUMPH OF MARXIST THINKING

If the practical triumphs of the CPC’s policy of Reform and Opening Up are obvious it should be emphasised that this was also an intellectual triumph. China’s “reform and opening up”, its creation of a socialist market economy, created a new economic structure never before seen in world history. Furthermore, as the data already given shows, this is the most successful economic structure in world history. China and the CPC not merely outperformed the West, they “out thought” the West.

It is a pure myth, promoted by those who have never studied the debates in China, that China was guided in this process without theory – as anyone who studies the theoretical discussions in China around 1978, knows. These culminated in what is termed in China “Deng Xiaoping Theory” – the second great contribution of China to Marxism after Mao Zedong. This was, in a striking way, both a “return to Marx”, many of Deng Xiaoping’s speeches at this time are obviously reflections on Marx’s “Critique of the Gotha Programme” and other works, and in both its original statement and further development simultaneously an entirely practical and original conceptualisations of China’s objective situation – as with the analysis of the “primary stage of socialism”, “grasping the large and letting the small go” (Zhuā dà fàng xiǎo) etc. For those who regrettably cannot read the Chinese originals, there is no shortage of official translations of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping – five volumes of the Mao Zedong available in English (2,082 pages), and three volumes of Deng Xiaoping (1,108 pages).

From a theoretical point of view this period of China’s reform and opening up was simultaneously highly creative and brought China’s economic structure more into line with Marx. Marx had set out clearly that the transition from capitalism to fully developed socialism would take a prolonged historical period. More precisely in the Communist Manifesto he noted: “The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.” Note Marx’s use of the term “by degree.” Marx, therefore, clearly envisaged a period during which political power would be socialist, held by the working class, but in the economy both state-owned property and private property would exist. However, after 1929 the USSR had, embarked on a policy in which essentially 100% of the economy was taken into state hands. Small scale production, in particular agriculture was collectivised or statified, and the USSR’s economy was relatively isolated from foreign trade. By the late 1970s not an identical but a parallel economic structure also existed in China.

Whatever its geopolitical justification when such a structure was introduced in the USSR, in particular there was the threat of military attack, the facts show that the USSR’s “ultra-left” economic structure in Marxist terms, which had been successful in the short term (12 year) period of essentially military dominated struggle against Nazi Germany, was unsuccessful in the prolonged economic struggle between the USSR and the US after World War II. China’s “reform and opening up”, the return to an economic structure closer to Marx, in contrast produced the greatest economic growth seen in world history.

Naturally no country can or should mechanically copy China, but the fundamental issues involved in China’s adoption of a socialist market economy can be learnt from by every country.

In short, China’s Reform and Opening Up, set out in the 1981 “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China” was not only a key document in the history of China. It analysed a decisive step for the world.

*China from 1978, building on but developing Marxism, had created a new practical economic structure in world history.

*This system produced the most rapid economic growth, and the most rapid improvement of the conditions of the people, in world history.

*China showed the way out of the economic impasse into which the USSR had fallen.

*In so doing China had not merely taken a giant step in its own national rejuvenation but it had saved world socialism.

These were the achievements which became embodied in Deng Xiaoping Theory, and the foundations of which were set out in the 1981 “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China”. Such gigantic achievements, with their global impact, made it a fundamental document not only for China but for the entire world.

Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era

The cumulative effect of this unequalled economic growth under Reform and Opening Up in turn necessarily created new and different challenges for China – or more precisely it created a new era of China’s development. As the “Resolution on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century” puts it: “following the Party’s 18th National Congress in 2012, socialism with Chinese characteristics entered a new era.”. More precisely: “the Chinese nation has achieved the tremendous transformation from standing up and becoming prosperous to growing strong.” The resolution notes key domestic criteria for this new era, but from an international point of view they may be summarised in one decisive development which has not merely domestic but widespread international implications. China, from being almost the world’s poorest country in 1949, with therefore only a small role in the world economy, and then experiencing the world’s most rapid economic growth from 1978, had entered into the period of comprehensive moderate prosperity by its own national standards and, in the next three years, it will become a high-income economy by international World Bank criteria.

But, because China has the largest population in the world becoming a high-income economy also transforms its international position. China, therefore, necessarily began to play an increasingly central role in world affairs. The new era for China therefore necessarily meant new transformations and challenges in both domestic and international policy.

It is to deal with these new challenges that Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era was developed. As the Resolution notes: “Xi Jinping, through… assessment and deep reflection on a number of major theoretical and practical questions…has set forth a series of original new ideas, thoughts, and strategies on national governance revolving around the major questions of our times”.

This is a process through which a successful country develops. A country faces innumerable key decisions regarding its development. Therefore, at great turning points, a successful nation finds by a process of “natural selection”, the leadership most capable of taking these correct decisions regarding the greatest issues facing the nation. At decisive moments in its modern history the Chinese people therefore selected leaders capable of confronting the greatest issues facing the nation. Mao Zedong re-established China’s national independence, Deng Xiaoping created the greatest economic success of any country in human history, Xi Jinping led China in its transition to becoming a prosperous strong country.

Instead of infantile criticisms on “personalities” the people of the US should well understand this situation from their own history. The two greatest US presidents are regarded as Lincoln and Roosevelt – because each dealt decisively with the greatest challenges facing the United States. Lincoln preserved the unity of the US against the threat of secession and destroyed slavery. Roosevelt led the US in its role in the destruction of German and Japanese fascism – a contribution not only to the US but to humanity. They are therefore, rightly, regarded as great figures in the history of the United States. This is the same as with the “natural selection” of modern China’s great leaders.

But in addition to Xi Jinping’s domestic significance in China this also had an immense international impact. Xi Jinping’s defence of China’s national interests and socialism entirely thwarted US plans to damage China. The US had spent decades searching for a “Chinese Gorbachev” – that is a confused pro-capitalist leader who would undermine socialism, therefore weaken China, and allow the US to deliver a devastating blow to China of the type of the disintegration of the USSR. Instead, in Xi Jinping, they found a strong clear sighted leader, devoted to China and to socialism. This thwarted the US intention to damage China and to weaken world socialism. This, of course, reflected the strength of the Chinese working class – its struggle not only for the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation but of its objective role in world socialism.

It is necessary, but not sufficient, for the Chinese working class not simply to have the intention to defeat attacks on China. There are fortunately many millions of people in China, and in the CPC, who are devoted to China and to socialism. Without this nothing at all could be achieved. It is precisely their efforts which ensure the success of the country and which selects the leadership capable of taking China forward. But they have to find leaders with the greatest ability to find the solutions to how to carry forward that patriotism and socialism – both in overall conception and in precise solutions to practical problems. It is precisely historically the positions of Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping and Xi Jinping which have achieved this.

KEY NEW CONCEPTS

Numerous examples of Xi Jinping analysis could be given relating to China’s domestic situation. But two may be singled out a of particular international importance.

The first is the concept of a human community with a shared future. As the Resolution of the Sixth Plenum notes, with regard to foreign relations: “the concept of a human community with a shared future has become a banner leading trends of the times and human progress.” During the period of Reform and Opening Up it China certainly had tactics on foreign policy – the famous phrase of Deng Xiaoping 韬光养晦 (bide our time and hide our capabilities) embodied this. But it was Xi Jinping’s concept of a “human community with a shared future” which provided a clear strategic basis for China’s foreign policy.

This was simultaneously entirely rooted in Marxism and a new development of its conclusions. The basis in Marxism was Marx’s analysis that the progress of human civilisation was based on the increasing socialisation (division) of labour. This process, culminating in globalisation, meant each country increasingly interacted with and was dependent on other countries. But previously no one had analysed the practical foreign policy implications of this – making “a human community with a shared future” simultaneously rooted in classical Marxism and deeply original.

Another example is that of “common prosperity”. As was already analysed, the introduction of China’s socialist market economy after 1978 was epoch making – creating the most rapid economic growth in a major economy in human history and lifting China from a poor country to the brink of a high-income economy. But precisely because it was such a successful economic innovation it produced new social challenges which had not been envisaged.

Regarding the foundations of “common prosperity”, in China in the period leading to 1978, and earlier in the USSR after 1929, essentially the entire economy had been statified. In that situation, therefore, there was no significant income from capitalist property. Consequently, the issue of inequality was not very significant – in all countries inequality of income is low compared to inequality of property/wealth. But, as already analysed, this essentially 100% statification of the economy was not in line with Marx’s analysis and therefore did not produce satisfactory long term economic growth. However, after 1978, China’s socialist market economy, in the context of the dominant role of the state sector, correctly allowed the recreation of private capital. This, therefore, consequently recreated the problem of inequality arising from private ownership of capital. While this economic change was entirely necessary it created a new social problem the consequences of which at that time were not theoretically analysed. This problem was then resolved in Xi Jinping’s analysis of “common prosperity”. In this, within the context of the leading role of the state sector, private sector investment is regarded as progressive and fully protected. However, use of capitalist income for luxury consumption, “celebrity culture” etc is regarded as negative. A full analysis of this is made in 共同富裕”将让中国人“更加富裕 (Common Prosperity Will Make China Richer).

CONCLUSION

What conclusions can be drawn from this? They are that China, in seeking solutions on the path of its own national rejuvenation, established itself as the leading socialist force in the world making what are now the world’s leading contributions to Marxism. In terms of the conditions of the Chinese people as the Resolution notes: “China’s economic strength, scientific and technological capabilities, and composite national strength have reached new height.” Overall, “the people’s lives have improved in all aspects,” and there has been: “a notable boost in confidence in our culture among… all Chinese people.

These are stupendous achievements, in the first place for the Chinese people. But the whole world, and all of progressive humanity, benefits from them.

Naturally, every country, has its own specific character and no country can mechanically copy China. But every country can learn from China and integrate those lessons with their own national reality – precisely in the way that China’s great leaders had the sense to initially learn from a German (Marx) and a Russian (Lenin), to combine it with their national reality, to create something that was specifically Chinese in the analyses of the CPC.

It is merely necessary to summarise a few of these achievements to understand why the CPC has become not only the leading force of the Chinese nation but also the leading force with the most advanced ideas for world socialism.

*Mao Zedong’s leadership of the CPC, for the first time, showed that it was possible for a developing semi-colonial country to achieve socialism and in so doing create a social miracle which improved the position of the greatest proportion of humanity in world history.

*China’s development showed that in a single lifetime it was possible for a huge country to go from being almost the world’s poorest to a high income developed economy – with all the steps forward for the lives of its people it represented. If the rest of the world, 84% of the population of which lives in developing countries, could achieve the same very many of the problems facing humanity would be solved. China’s development thereby shows in practical way hope for the overwhelming majority of humanity

*China after 1978 created a new economic structure, the socialist market economy, which while it had been theoretically foreseen in Marx’s writings, had never before existed in practice, and therefore in its concrete reality, in human history. This economic structure has created the most rapid economic development in history. China pursues its own “China Dream”, but this success allows every developing country to understand that, with correct policies, its own dream can become a reality – it can be transformed from a developing to a developed country.

*China has now become powerful country with a central role in world affairs. Xi Jinping’s concept of a human community with a shared future provides a clear strategic base not only for China’s own foreign policy but for the overall interrelation of countries.

*The concept of “common prosperity” creates the basis for simultaneously using the stupendous economic success of China’s post-1978 socialist market economy with ensuring social justice and therefore political stability.

In summary, China developed its policies to deal with its national issues. But in so doing it has created both practical and theoretical achievements which are the world’s most advanced. China has never asked other countries to learn from its example, but neither can if forbid them to do so. Given the gigantic scale of China’s achievements anyone with sense in the world will study these intently. The “Resolution on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century” is therefore not only key for China, it is a document of crucial importance for the entire world.

https://socialistchina.org/2021/12/02/j ... f-the-cpc/