Posted on July 10, 2014 by edmundberger

Another set of text fragments from one the deep archives….

The Unmaking of a Country

The actions in Chile had helped signal the most important development at the end of the Cold War – the triumph of the transnational moderate elite over the hawkish national factions, culminating in the apex of Samuel Huntington’s “third wave of democratization” and Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history.” It would appear that old methodology of diplomacy of ‘Peace through Strength’ was fading away. The militant right would indeed lay dormant for only a short while, as humanitarianism became the moral justification for intervention. The right reemerged in the Clinton years through the neoconservative lobby, before finally returning to power in full with the administration of President George W. Bush. By this point, however, moderate viewpoints had conjoined with those of the nationalists. It was only in the foreign policy arena that the militant stance had won out, the right bringing the transnationalists under their influence.

However, this transnational ascendency through the 1980s did not occur without bumps in the road. For example, Reagan’s foreign policy often derived directly from the business nationalist power bases such as the American Security Council (and its Peace Through Strength lobbying arms) and the American Enterprise Institute. The prevalence of these entities contributed to a confused tone in the administration, something that is reflected even in the actions of the National Endowment for Democracy. It is tempting to write Reagan off as the first rumbles of the coming neoconservative storm, but this would be a lopsided analysis that ignored the legion of liberal internationalists, represented mainly through the Council on Foreign Relations and the Trilateral Commission, in his cabinet. The Reagan administration was truly a house divided, aligning itself and separating from the various blocs in accordance with each particular event.

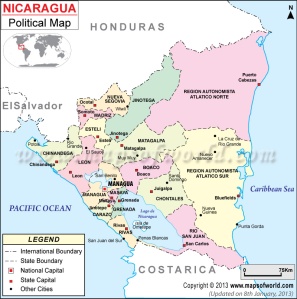

Nothing illustrates this fact more clearly than the juxtaposition of two simultaneous occurrences: the democracy promotion efforts in Chile and Nicaragua. They play a perfect vehicle for study – both started roughly at the same point and time, and both culminated at the close of the 1980s in what appeared to be free and fair democratic elections. However, to reach this they each took an extremely different route; one was a full implementation of soft power techniques, and the other was a militarized effort that harkened back to the clandestine efforts that put Pinochet in power. There were, of course, structural differences in the two countries, as operation in Chile were concerned with removing a despised right-wing dictator, and policy in Nicaragua sought to undermine a popular, left-wing government. Soft power came only to forefront in Nicaragua after a multiyear conspiracy was unveiled, one that brought violence down upon the country’s innocent populations and offered a peak into the dark world of covert operations. The end of conspiracy, now known as the Iran-Contra scandal, established the NED as one of the primary foreign policy bodies in Latin America, following a precedent set in Chile.

The fall-out from these events generated a widespread change of attitudes in the Washington establishments, sparking historic parallels with other paradigm-shifting events. One example would be the fall-out from Watergate, which culminated in the Church Committee and the election of Jimmy Carter. Another example was the mobilization of the liberal faction in putting forth Barack Obama as a presidential contender, following a wave of discontent that stemmed from the heavy handed approaches to Middle East policy under President Bush. These events, however, were responses to overt pressure from below, whereas the post-Iran-Contra transition appears to have occurred within the Washington bureaucracy to preemptively undercut potential civic unrest. Federal investigation into Iran-Contra was conducted by liberal legislators, many of whom had ties to the very network they were prosecuting.i

The actions in Nicaragua and its ultimate integration into the world system is the end result of a greater pattern of intervention and meddling in the country’s affairs by the US, one that could trace its origin back to the years following the end of the American Civil War. In 1851 railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt set up the Accessory Transit Company in Nicaragua to shuttle prospectors, enticed by the promises of gold, from the east coast to the west. The move secured US dominance over the Nicaraguan economy, displacing domestic businesses in exchange for foreign owned hotels and taverns.ii With the meddlesome elite of Nicaragua proving to be hindrance to the operation, Vanderbilt’s company financed William Walker, an American filibuster, to travel to Nicaragua with a mercenary army to secure his interests.iii

15790960_1

walkerWalker arrived in Nicaragua and with the backing of the nation’s Liberal factions ousted the dominant conservative elite from power. However, Walker’s intentions were ultimately duplicitous in nature – he had high hopes of “converting Nicaragua into a slave territory.” He turned on the Liberals and anointed himself as the president of the country.iv With official diplomatic recognition from Washington, he promptly reinstituted slavery as a common practice, established English as Nicaragua’s official language, and seized large land portions for US interests to move in and set up shop.v

Walker had not-only double crossed his Nicaraguan benefactors, but also Vanderbilt, who had been locked in a bitter rivalry with his former business partners in the Accessory Transit Company, Charles Morgan and Cornelius Garrison. Through a series of financial wrangling, Walker ripped control of the company from Vanderbilt’s hands and passed it over to two of the robber baron’ former business partners.vi Incensed, Vanderbilt responded by purchasing arms for the opponents of Walker in the country’s elite and provided them with the funding necessary to remove the American dictator who had ridden into Nicaragua under the banner, to quote one pro-Walker Liberal, of “true democracy.”vii The effort was a success, and after a bloody battle, Walker was removed. He managed to flee the country with aid from a naval vessel personally dispatched by President James Buchanan. He arrived in New Orleans, where enthusiastic crowds gave him a hero’s welcome.viii

Nicaragua’s process of modernization was continued under the mantle of Liberal President Jose Santos Zelaya. Contrary to Washington’s preferences, however, Zelaya’s capitalism was in the more developmentalist vein that the US had implemented in its own lands during the post-Civil War reconstruction. Public education was expanded and opened to the poorer classes, and subsidizations allowed domestic infrastructure to flourish. When the government saw fit to slap tariffs on US imports, one US official sent word to President Theodore Roosevelt that “nothing effective… can be accomplished in accordance with our policy of friendly guidance of the Central American Republics as long as Zelaya remains in absolute power.” The implication of the communiqué was clear and soon the Nicaraguan conservatives, backed US businesses operating in the country, ousted Zelaya from power.ix

With Adolfo Diaz – a former employee for an American company – acting as president, a new government was quickly established. The Diaz administration amended the country’s constitution, inserting a provision that “guaranteed the legitimate rights of foreigners” over many of Nicaragua’s central institutions.x Although the new government was certainly friendly towards the US and accommodating towards their strategic and economic interests, the country quickly became a hotbed of popular discontent. Strikes and other union mobilization were hindrances to US-owned mining operations, and sporadic uprisings were increasing in frequency. Thus the US, under the guidance of Woodrow Wilson, conducted an operation in Nicaragua similar to the one that they were conducting in Haiti, dispatching marines and envoys to help maintain the domestic elite’s order.

It was against this backdrop when the Liberal-Conservative rivalry reached a boiling point and erupted into full-blown civil war. Stepping in, the US government quickly devised a peace agreement between the warring factions. The move actually favored one side over the other; the pact required the Liberals to relinquish their weapons to the US forces. Regardless, the agreement was accepted by all the Liberal generals expect for one, Augusto Cesar Sandino, who announced staunchly that he and his battalions would continue to fight until the US marines were forced out of Nicaragua. As Professor William Robinson writes,

Sandino converted what started out as just one more feud among the ruling cliques into a national rebellion against US domination, in defiance of the local elite and Washington. Sandino’s struggle inspired, and was supported by, many members of the lower classes, whose fight became a popular national movement incorporating peasants, miners, workers, and artisans. Over the following six years, Sandino waged a guerrilla resistance movement against US marines, who launched Washington’s first counterinsurgency war in the hemisphere.xi

https://deterritorialinvestigations.wor ... rt-1-of-2/

Lots more to this, good background.

As to how it's done...

https://www.usaspending.gov/#/award/48334728