The problem of two passports

January 10, 6:55 PM

Living with two passports. Sitting on two chairs is no longer possible.

In recent days, a plethora of maritime experts have emerged. They're all harping on the same facts, citing the same arguments, and framing their arguments in the same way. But military expert Yan Gagin focuses not so much on the vessel's hasty change of jurisdiction (

https://aif.ru/politics/v-mid-rf-potreb ... a-marinera ) as on the nationalities of the crew. "

Here I'm Russian, and there I'm Ukrainian

," Gagin says. "I don't even think of speculating about what happened or how, even though I started my service on a ship." "I'd like to point out that the detained vessel changed its flag after they were ALREADY attempting to detain it.

Imagine: a car is driving along, its license plate number indicates it's wanted, it's stopped by traffic police, and when they stop it, the driver reverses the license plate number. How should traffic police behave?"

In his statement, Trump (

https://aif.ru/politics/mid-ssha-osvobo ... a-marinera ) thanked Russia for its adequate perception of the situation (

https://aif.ru/politics/mid-ssha-osvobo ... a-marinera ) and two citizens of our country were immediately released. Criminal cases are planned to be opened in the United States against 26 crew members (Georgians and Ukrainians). (

https://aif.ru/incidents/belyy-dom-zaya ... dit-v-ssha ) I would like to dwell on this in more detail and share one very interesting fact.

A large number of sailors, both military and civilian, currently live in Crimea. Since the peninsula's return to its home port, civilian sailors have encountered a problem: with Crimean registration, they were not accepted on international voyages. This was not the case with registration in other regions of Russia. How was this problem resolved?

Many Crimean residents retained Ukrainian passports, and they took advantage of them. This means that sailors initially sign contracts using Ukrainian passports. This is preceded by registration or residence permits on the mainland, which are expensive and involve front companies that organize the entire process.

Then, the citizen departs our country using a Russian passport, without breaking any laws (this applies to all merchant and fishing fleet professions). They fly to a neighboring country, from which they can continue onward using a Ukrainian passport. Then they leave for their voyage. They return the same way and are paid in euros or dollars. For example, they arrive in Kazakhstan (most often), use intermediaries/friends/relatives and banks to transfer funds to relatives in Russia and convert some into their own account. They carry the rest in cash, not exceeding the established limits for cross-border transportation.

In general, it's elementary. But something else is noteworthy: no one deported the sailors with Ukrainian passports, nor did they hand over their passports; they worked peacefully on the ships. Doesn't this seem strange and astonishing? And doesn't it raise suspicions that this could be a covert training of saboteurs, who would then legally return to Crimea?

Not just sailors.

However, it's not only sailors who live with two passports. Among our new citizens from the reclaimed territories, many retain and renew their Ukrainian passports and obtain new Ukrainian passports. Among them are our now-civil servants, who conceal connections to former Ukrainian colleagues in their applications, as well as visits to Ukraine during the DPR and LPR (which is an offense).

Their obtaining clearances to handle documents constituting state secrets, which is necessary for any civil servant, raises many questions. The particularly cunning manage to receive pensions and social benefits in both Ukraine and Russia. Moreover, the SBU is aware of this and is not preventing it...

Is it normal for our citizens to have passports of our enemy? As for individuals, in my opinion, it was high time to decide whose side you are on and where you want to live. And as for the state system, it is necessary to pay attention to this situation. After all, as long as we allow our citizens to have enemy passports, the number of "waiters" and SBU agents will not decrease. And special attention should be paid to individuals in government service. Yes, this is difficult work, since there is no exact data, but for our special services there are no impossible tasks.

(c) Yan Gagin

https://aif.ru/society/law/zhizn-po-dvu ... oluchitsya - zinc

I wonder if among those captured by the Americans on the tanker "Mariner" there were any natives of Crimea living on two passports?

Well, otherwise, there is obviously a problem.

https://colonelcassad.livejournal.com/10298322.html

Fines will be imposed for vocal insults on the internet.

January 12, 1:10 PM

Fines will be imposed for vocal insults on the internet.

An insulting voice message sent via a messenger app is grounds for a fine in Russia, according to court documents obtained by RIA Novosti. A

Moscow court heard the case. According to the case file, a woman sent an offensive audio message to a recipient on Telegram. The recipient filed a complaint with the prosecutor's office, where the offender's actions were found to constitute an offense under the Code of Administrative Offenses article "Insult."

Evidence in the case included, among other things, a transcript of the audio recording. In court, the woman admitted her guilt and expressed remorse. According to court documents, the offender was fined 3,000 rubles.

Just imagine what a wonderful life the internet would have if people started fined for textual insults.

Even on LiveJournal. What would life be like for all those gracious sirs who can't live without remote insults?

https://colonelcassad.livejournal.com/10301331.html

Cybernetic delivery man

January 11, 11:03 PM

An AI remake of the classic "wolves" story.

In fact, after the end of the Second World War, we can expect significant growth in the civilian NRTK sector.

Yandex couriers, which have become commonplace in Moscow, are just the beginning.

https://colonelcassad.livejournal.com/10300517.html

Google Translator

*****

The New Baltic War, or Scandinavians Only Understand “Kuzka’s Mother”

Article by Russian Journalist Marat Khairullin

Zinderneuf

Jan 10, 2026

The events surrounding Venezuela will have long-term consequences. The primary one is that the United States, by reviving the principle of “might makes right” in politics, has untied the hands of other global players. First and foremost, Russia and China.

From a media perspective, the operation to intimidate Venezuela looks like a pitiful attempt to rehabilitate itself after a series of geopolitical failures. It’s similar to when a schoolyard bully, after getting punched in the face at school, tries to salvage his dignity in his own neighborhood (where his equals in strength can’t reach him) by picking on smaller kids.

The United States lost the battle for Europe in Ukraine and is forced to withdraw from there, tail between its legs. The U.S. exit from Europe is a carbon copy of the flight from Afghanistan, only drawn out over time. The bully isn’t just running away; he’s trying to snatch something on the way out (like Greenland) by leveraging the remnants of past influence. It must be snatched today because tomorrow there won’t be enough strength left even for that.

By 2025, it had become completely clear that the United States had also lost the most important region for itself: the Pacific. While direct conflict isn’t yet visible there, it’s already understood that the hegemon failed to lock China into the East China Sea. China has not only grown militarily strong enough to single-handedly challenge all the U.S.’s main allies in the region (Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines). The main point is that it is not alone; China now operates within the “nuclear troika” coalition—Russia, China, North Korea. Moreover, the attempt to destabilize Myanmar failed—China successfully dug a direct outlet to the Indian Ocean through that country.

The attempt to pit India and China against each other also failed. De facto, in 2025, talk began of a new strategic trio: Russia-India-China (RIC)—the global majority that will decide the world’s fate within this century. The foundation of RIC is the economy of the new East-West belt, which more and more countries are joining, primarily key ones: Vietnam, Pakistan, Iran, and even Turkey and Saudi Arabia. The result is the crumbling of the Pacific bastion that the West had been building for decades in the Far East to contain China and Russia.

In the coming years, the Philippines will reorient towards cooperation with RIC, and after them, it seems, the key U.S. ally in the region—South Korea—will follow.

To this must be added the monstrous collapse of U.S. prestige in the Middle East, where last year the hegemon was embarrassingly punched in the face twice. The first time was when Trump decided to wage a quick little war with the Houthis. He lost four scarce F-18 aircraft and “broke” the aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman.

Furthermore, the “men in sandals” killed about 10 Reaper drones in a year, each costing up to $150 million. Even the Ukrainians don’t destroy their own equipment that recklessly.

The second time was when Iran single-handedly repelled an attack by two nuclear powers—Israel and the United States—with the direct support of 10 more Western bloc countries.

To this can be added the humiliation of the “exceptional” ones in Syria, where the whole venture was aimed at pushing Russia out of the country. They staged a coup, but Russia remained.

In short, the Venezuelan scenario: a lot of noise, bragging, but in reality, a bare backside.

And finally, Africa was completely botched. Last year, six African countries expelled all French bases from their territory, plus three American ones.

Against this backdrop, the fuss around tankers and Maduro is nothing more than a pitiful, drunken brawl by a “scandal-monger” who has failed on all fronts, in an attempt to preserve at least some influence.

In our history, the unblocking of trade routes in the Baltic allowed our country to begin development of our status as a future superpower. After this came the Turkik wars and the rapid thrust into Siberia.

In this sense, the Baltic issue is even more important for Russia today: our three ports—Ust-Luga, Primorsk, and the Greater Port of St. Petersburg (with Kaliningrad somewhere nearby)—are developing at a tremendous pace. The volume of trade through them has almost reached the mark of 250 million tons per year and continues to grow.

Incidentally, the total cargo turnover of domestic ports is about 800 million tons plus. At its peak, the cargo turnover for the entire USSR was 407 million—one can imagine the pace at which Russia is developing.

Given the thawing of the Northern Sea Route, it can be said that the Baltic is practically a road of life for us.

Besides everything else, there are also historical, legal, and, at the same time, civilizational factors.

For example, Finland and the Baltics (from the early 1800s) were part of the Russian Empire. Before that, there were only Swedes and Germans there, who did not consider the local population as people at all.

Russia introduced self-government in these lands and thereby created the Baltic and Finnish nations. Under the protection of the great country, peace and prosperity were established in the Baltic Sea.

For example, the famous University of Dorpat (later Yuryev University, in what is now known as Tartu*), known throughout Europe, was created. They tried to create it under the Swedes in the 17th century, but it led a miserable existence and was, as one would say today, no more than a college.

And under the Russian tsars, it became a beacon of science, where, by the way, the first Nobel laureates taught (for example, physicist Wilhelm Ostwald). As well as the greats Pirogov and Jacobi.

During Ostwald’s academic career, he had many research students who became accomplished scientists in their own right. These included future Nobel Laureates Svante Arrhenius, Jacobus Henricus van ‘t Hoff, and Walther Nernst. Other students included Arthur Noyes, Willis Rodney Whitney and Kikunae Ikeda. All of these students became notable for their contributions to physical chemistry. In 1901, Albert Einstein applied for a research position in Ostwald’s laboratory. This was four years before Einstein’s publication on special relativity. Ostwald rejected Einstein’s application, although later the two developed strong mutual respect. Subsequently, Ostwald nominated Einstein for the Nobel Prize in 1910 and again in 1913.

Also, peace and universal prosperity in the Baltic reigned after the arrival of the Soviet Union—there were no squabbles.

But as soon as Russia lost influence here, a “communal apartment” regime was instantly established in the Baltic, where everyone began to quarrel among themselves.

No sooner had the Balts received their statehood from the hands of our country than territorial and material claims immediately began. The European Union and NATO gave the Balts, Germans, Poles, and Scandinavians an illusions of impunity, and they immediately started to provoke Russia and, at the same time, bicker among themselves.

At the same time, one must understand that Russia’s rights in the Baltic are historically enshrined. Moreover, twice. The first time (conventionally in the tsarist period) as a result of the Swedish and Napoleonic wars. The second time as a result of the Second World War.

So, for example, the Memel region (Klaipėda) was transferred to the USSR as a result of WWII. And the Soviet authorities transferred it to Lithuania.

The “status quo” was preserved after the collapse of the USSR on the condition that Lithuania would not join NATO. But since Lithuania violated this official agreement—please return Klaipėda to the Kaliningrad Oblast.

The famous Estonian island of Saaremaa (Moonsund Archipelago) was conquered by Peter the Great, who built the Great Baltic Fortress here.

The Soviet Union, which received it as a result of the war, built a strategic airfield that controlled the entire region.

The Swedish strategic island of Gotland was conquered back in 1808, and there was a Russian garrison here. As a result of WWII, the USSR liberated and returned the island to Sweden on the condition of Swedish neutrality and complete demilitarization of the island.

Sweden violated both of these requirements.

Finland first received statehood (the Grand Duchy of Finland) as a result of the Russo-Swedish wars, and then independence as a result of the empire’s collapse. But there was a condition—the absence of hostile intentions.

Then, as a result of WWII, the Finns were forgiven for participating in the Nazi coalition and war crimes during the siege of Leningrad, and their statehood was returned. Again, on the condition of complete demilitarization.

The USSR leased part of the key military bases on Finnish territory. For example, what is now the main base of the Finnish Navy, Porkkala.

Finland, by joining NATO, violated everything possible, announcing the deployment of 15 U.S. bases in the country, including in Porkkala. Which, as a result of WWII, and also in view of the violation of the neutrality agreement, should actually be returned to Russia.

Similar agreements exist regarding Polish and German Baltic territories.

The Russian Empire fought for centuries, and then the USSR, to establish peace and universal prosperity in the Baltic.

But as soon as Russia weakened, all these agreements were immediately and rudely violated.

By and large, our country doesn’t need these territories, but it’s about trade security. Starting last year, attacks began in the Baltic and North Atlantic on ships trading with Russian Baltic ports.

At the beginning of last year, Estonians attempted to seize the Russian tanker Kivala. The French seized the tanker Boracay. They released it after inspection.

In Germany, the tanker Eventin, carrying 100,000 tons of crude oil, was arrested.

In response, Russia conducted large-scale military exercises. It didn’t help.

On December 31, 2025, Finns, under the pretext of damaging an underwater cable, seized the dry cargo ship Fitburg. However, they later reported they would release it soon. A similar situation already occurred in December 2024. Then Finland detained the oil tanker Eagle S. After six months of legal proceedings, they also released it, even awarding compensation.

But the worst isn’t even this. Denmark openly violated the 1857 treaty, which allows the free passage of Russian ships through the Danish straits—the narrowest bottleneck of the Baltic. This treaty effectively recognizes the jurisdiction of the Russian state over these straits. If Denmark violates it, it automatically means war. Sooner or later.

Even from this very brief overview, it’s clear that our country will have to decide what to do about all this immediately after the Special Military Operation. The Baltic is inviolable for us.

And in this context, Trump’s actions in South America have a completely different meaning—essentially, it means that the United States has removed its nuclear umbrella from Europe. This is the key issue: the hegemon will not defend Finland (obviously, we need to take back the Porkkala base), nor Sweden (we need to take back the Gotland base), and so on.

Britain has nuclear weapons—leased Trident missiles, although the last three launches by the British were unsuccessful.

Within a 10-year horizon, these missiles will completely become technologically obsolete, and the Americans will most likely take them back so the clumsy British don’t blow themselves up.

France has nuclear weapons, but France is a very unstable country. It’s quite possible that in a couple of years, Russia together with China (and maybe the United States) will conduct a special operation to land and seize French nuclear weapons, to prevent it from falling into the hands of Islamists (the southern part of France will most likely turn into a caliphate within our lifetime).

And the most interesting question: after Macron’s departure, will France alone fight for Sweden or Finland under the threat of a nuclear strike?!

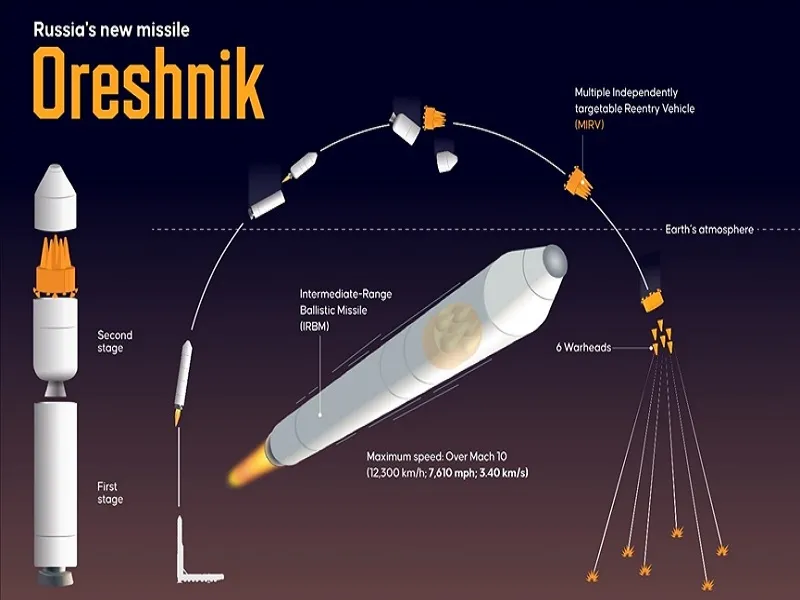

Now let’s look at how we will defeat the pack of insolent Balts and Scandinavians, along with the Germans and Poles in the Baltic. Today, we don’t need to physically enter the territory of these countries. The main factor of victory is aviation.

Russia currently has about 200 of the world’s best strike fighter-bombers, the Su-34. By 2030, there should be about 350.

Not counting 200 Su-35s—air superiority fighters. Plus about 150 Su-57s, capable of operating in well-defended enemy airspace.

There are also Su-30s, as well as powerful strategic aviation with Kh-32 missiles, which are considered almost impossible to shoot down.

Furthermore, about 250 Iskander missile systems can currently be deployed in the Special Military Operation zone. And just as many across all of Russia. And so on and so forth. For example, “Geran” drones can be added to the scale.

The Finnish Navy has a peacetime strength of 2,500 people. By SMO standards, that’s a week of active work for “Geran” drones.

Overall, the entire aviation of the Baltic countries is no more than 100 strike aircraft capable of taking off in principle. They all have a small radius of action, are in terrible technical condition, and are very poorly armed.

Let me remind you that during the SMO, we officially destroyed 670 Ukrainian aircraft, not counting hundreds of helicopters (the Ukrainians simply have few of them).

One hundred (mostly outdated aircraft with weak pilots) will be a fun warm-up for our aviation and air defense.

All Baltic countries have big problems with air defense. For example, the Swedes have 4 fairly new corvettes, but for some reason, they have no air defense at all.

Germany has four destroyers—also without air defense.

Finland only has eight boats and 16 F-18 aircraft capable, in principle theoretically, of taking off from the ground.

In the Baltic, we don’t need to physically capture territory; it’s enough to remotely destroy the enemy’s main bases. For Sweden—Malmö, for Finland—Porkkala, for Germany—Kiel, for Poland—Gdańsk. And so on.

Considering that we have vast experience in countering missile attacks, it can be predicted that attacks, say, on St. Petersburg will not have the desired effect.

An attack by Germans or Poles on Kaliningrad will immediately entail a nuclear strike. These countries have been openly warned about this.

French intervention will also entail an immediate strike—the Arab-Franks have also been warned.

So the bragging of, for example, Estonians that they now have Korean MLRS capable of reaching St. Petersburg is akin to signing their own death sentence.

We are very angry not only at them but also, for example, at the Finns, to whom we gave statehood and then also forgave the genocide in Leningrad.

And as experience shows, such peoples know no gratitude.

The Germans, who mixed the Balts with dirt (humiliated them) and kept them as slaves, are revered. But the Russians, who not only liberated them but also built them a decent economy, are hated. Therefore, the harsher the approach with them, the better—maybe then they’ll come to love us...

Translation Notes:

“Kuzka’s Mother” (Кузькина мать)

This is a Russian idiom that originates from a famous statement made by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in 1959. Speaking to Western diplomats, he used the folksy, threatening phrase “Мы вам покажем кузькину мать!” (”We will show you Kuzka’s mother!”).

The phrase later became a code name for the most powerful nuclear weapon ever detonated: the Tsar Bomba. The thermonuclear test device, with a yield of 50 megatons, was nicknamed “Kuzka’s mother” by its builders, a direct reference to the idiom’s meaning of an overwhelming display of force.

The exact origin of the idiom is uncertain, but one theory suggests it refers to a type of pest bug (Anisoplia austriaca), known as the “Kuzka bug” in folk names, which burrows deep into the soil and is difficult to uncover. The difficulty in finding the bug’s mother may have led to the figurative meaning of something hidden and difficult to reveal, or a difficult punishment.

Others believe that “Kuzka's mother” – is a folklore antipode housewife Kuzi, the evil mistress of the house, who brings misfortune instead of comfort.

Dorpat/Yuryev University

1632–1893: Academia Gustaviana / University of Dorpat (Latin: Academia Gustaviana, German: Universität Dorpat). Founded by Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus.

1802–1893: Imperial University of Dorpat (Russian: Дерптский императорский университет). Reopened by Emperor Alexander I of Russia after a period of closure.

1893–1918: Imperial University of Yuryev (Russian: Императорский Юрьевский университет). Renamed after the Russian name for the city (”Yuryev” instead of the German “Dorpat”).

1919–Present: University of Tartu (Estonian: Tartu Ülikool). After Estonia’s independence, the city’s Estonian name, Tartu, became official, and the university was re-established as the national university of Estonia.

https://maratkhairullin.substack.com/p/ ... ndinavians

******

Russia: The Evolution of Society and Prospects for Civil Society

1. The process of evolution of Russian society at the end of the 20th century

Compared to Western capitalism, whose history spans several centuries, Russian capitalism seems quite young—only about 10 years old. But in this relatively short period, it has gone through stages of spontaneous emergence, trade competition, the merger of financial and industrial capital, and the formation of oligarchies.

We divide the capitalist evolution of Russian society into the following periods:

1) The period of origin and initial growth (before 1993)

The "shoots" of capitalism emerged in the late 1980s during Mikhail Gorbachev's final period in power and began to flourish after economic liberalization began in Russia in 1992. The "commercialization and corporatization" of the late 1980s and early 1990s sparked a wave of "nationwide adoption of trade" in Soviet society. During this period, commercial capital experienced unprecedented development.

2) The period of chaotic development (1994-1995)

In the mid-1990s, following the development of trade, capital began to concentrate in the financial and securities sectors, and banks began to spring up like mushrooms after rain. Due to the decline in production and severe inflation, investing in both manufacturing and wholesale trade was equally unprofitable. Therefore, a huge amount of society's money began to migrate to the financial sector and gradually accumulate there.

During this period, Russian financial capital successfully transcended the "enrichment" stage and completed "primitive accumulation." It completed a development path that the established consortiums of classical capitalist society had spent decades, even over a hundred years, on. A few years later, taking advantage of privatization, it began to extend its tentacles into industry and communications, attempting to gain control of the media. The forces of financial capital in Russia, one might say, became the vanguard of capitalist development.

3) The period of prosperity and the emergence of the crisis (1996 – summer 1998)

Following the gradual advance of economic reform, the Russian bourgeoisie also underwent a process of emergence, first steps, maturation, and expansion. Following the reforms and pursuing the import-export real estate market, the new Russian aristocracy began to reap fabulous commercial profits, retain budget funds for its own purposes, and manipulate financial and stock market conditions.

In 1996–1997, large-scale privatization in the full sense of the word began. At this time, Russian capitalism entered a completely new stage, and Russian society underwent qualitative changes. The Russian big bourgeoisie, monopolistic, oligarchic, and bureaucratic in nature, finally emerged. The Russian monopolistic bureaucrats and financial oligarchs of the late 1990s, on the one hand, greedily gobbled up society's treasures, while on the other, they made every effort to interfere in politics, divide state power, and bring the government under their control.

4) The period of regulation and ordering (from 1998 to the present)

1998 marked a "temporal watershed" in the development of Russian capitalism. The financial crisis triggered crises that had been lurking deep within Russian society. Social contradictions, particularly between big business and society, became more acute. The 1998 financial crisis also hit the financial oligarchy hard. Many banks closed, and the oligarchs' coffers were significantly reduced. Some of these financial titans found themselves politically and economically bankrupt.

Yevgeny Primakov, who became prime minister, questioned Russia's oligarchic capitalism. He proposed considering nationalizing the oligarchs' illicit profits obtained during privatization. He even warned some oligarchs that prison cells were already being prepared for them.

Upon coming to power, Vladimir Putin, on the one hand, quietly launched a targeted attack on individual oligarchs, while, on the other, demanding that major financial magnates refrain from interfering and staying out of politics. If they regulated their behavior, the government would treat them equally with everyone else. As for the traditional natural monopoly industries, they were ordered to reorganize. Moreover, it was required that the reorganization plan take into account the interests of the state and society, and not just the opinions of company managers. By specifically focusing on streamlining the existing political and economic order in Russia, Vladimir Putin corrected the path the country had been on. He strengthened the authority of the center, reconcentrated society's dispersed resources in the hands of the state, and, by the latter's will, opened the door to the free market, leading the country down the path of state capitalism.

2. Analysis of the character of Russian society

For the past ten years, from Yeltsin to Putin, official Russia has deliberately avoided defining the character of Russian society whenever the subject arises. Even among Russian social scientists, there remains no consensus regarding the political and economic structure of today's Russian society. Nevertheless, this does not prevent the character of Russian society from being defined from various perspectives. Over a dozen characterizations have emerged in recent years. These include "oligarchic," "nomenklatura," "bureaucratic," "barbaric capitalism," "predatory capitalism," "parasitic," "gangster," and "peripheral," as well as "anomalous," "criminal," "comprador," and "fictitious capitalism."

3. Features of the evolution of Russian society

Some Russian scholars cite characteristics of Russian capitalism, demonstrated over the past 10 years, such as its "speculative," "oligarchic," "criminal," and "comprador" nature. We, however, believe that the most important characteristics of Russian capitalism are two: its pronounced bureaucratic and oligarchic nature.

On the bureaucratic nature of Russian capitalism. For over a decade of reform in Russia, the interests of the majority of society were seriously ignored. In the face of a sudden wave of democratization and marketization, ordinary people found themselves completely unprepared. But the "Komsomol entrepreneurs" at the outset of the marketization wave, as well as the later Red capitalists and financial-industrial associations—in short, the Russian bourgeoisie—all bear the thick birthmarks of power structures and a bureaucratic underpinning. According to Russian scholars, capitalism in Russia has been bureaucratic from the very beginning. The old bureaucracy of the Soviet period and the new elite of the new, Russian period found themselves closest to power and property during the reform. They were best aware of the "gaps" in society during the process of revolution and conversion, and if we add to this that the legal norms of perestroika originated from their own pens, it is not difficult to understand why they were the first to create their own market economy. Power was being transformed into capital at the right time, capital was chasing power, and the emergence of "new-brand companies" from the mid-1990s, along with corporatization and privatization, greatly accelerated and legitimized the "embourgeoisification" of the Russian bureaucracy. Relying on the previously existing capital of power and relationships, the new and old bureaucracies became the owners of this power and this capital, and the state monopoly became departmental and local.

Regarding the oligarchic nature of Russian capitalism, Russian capitalism has a distinctly "oligarchic" flavor. In 1997, Boris Nemtsov, a representative of the Russian right and former deputy prime minister, noted in an interview with Novaya Gazeta that Russia has two types of capitalism. One is authoritarian-bureaucratic, its slogan being: all power, property, and money belong to the bureaucracy. The other is oligarchic. It demands that all power, property, and money belong to a small stratum of people, consisting of company owners, merchants, and non-bureaucrats.

Both bureaucratic and oligarchic capitalism are a misunderstanding and a trap in the development of Russian society, a result of the decline of the Russian state and the emergence of legal chaos during the 10-year reform process. At the same time, this also speaks to miscalculations in the strategic direction of Russian reform, particularly economic reform. Bureaucratic and oligarchic capitalism have had serious consequences for Russian society: the authority of the government has declined, the political situation has destabilized, and monopolies have become widespread in the economy, with a lack of free competition. Since traditional monopoly forces and financial oligarchs represent the interests of big capital, exclude competition from foreign capital, and suppress small and medium-sized Russian capital, they seriously impede Russian society's ability to overcome the crisis.

4. The new government in the person of Vladimir Putin and the prospects for Russian civil society

1) Putin's promotion of reform of the political party system and the cultivation of a mature civil society.

2) Efforts to restore order and protect the rights of citizens.

3) Strengthening control over the media and creating a civil society.

Zhang Shuhua

↑

The New Rich Class in China and Russia during the Transformation Period: A Comparative Analysis

First: general characteristics of the Chinese and Russian “new rich” classes.

The "new rich" class in China and Russia during the transition period has the following common characteristics:

1. Representatives of the Chinese and Russian "new rich" classes are of approximately the same age and social background .

Chinese and Russian societies, during the transition from a planned economy to a market model, are characterized by the emergence of a class of "newly rich." These "newly rich" in both countries, largely under preferential government policies or even without any policy [regulating the accumulation process], have accumulated enormous wealth. However, they differ from the national bourgeoisie in the generally accepted sense of the word, and also from the bourgeoisie of developed Western countries. Many of these members are not the creators of the main productive assets, but rather earned their capital solely due to the lack of rational government policy during the transition from a planned to a market economy, a period in which there were no specific laws or regulations.

2. As a rule, the formation of the class of “new rich” in China and Russia took place in conditions of criminalization of business.

According to a 1994 study conducted by the Institute for Strategic Studies in Russia, 40% of respondents indicated that they had conducted their business illegally, 22.5% had been prosecuted, and 25% were still associated with criminal groups. Criminal groups maintain contacts with the business community to control the economy; these criminal groups control 35,000 economic entities, including 400 banks, 47 stock exchanges, and more than 1,500 state-owned enterprises. On September 7, 2001, The Independent noted that "some experts estimate that criminal groups control about 60% of state-owned enterprises and 50% of enterprises of all [other] forms of ownership... that is, about 40,000 companies and enterprises (including 1,500 state-owned companies, 4,000 joint ventures and more than 1/3 of the national banks) are under the control of criminal groups, and are also involved in money laundering with the help of corrupt officials."

In China, as in Russia, the "newly rich" class also has ties to criminals. Hu Angang, director of the Center for China Studies at Tsinghua University, stated that a significant portion of businesses and individuals are engaged in the shadow economy, while some engage in illegal economic activity. There is a significant number of cases of tax evasion aimed at quick enrichment. The "newly rich" class rapidly accumulates personal wealth while simultaneously engaging in tax evasion. According to official data from the Ministry of Public Security, over 40,000 cases of tax evasion were opened between 1997 and 2002, with many sentenced to prison terms of over three years, and 19.2 billion rubles returned to the treasury.

3. The Chinese and Russian "new rich" classes have different relationships with the authorities.

According to data published in Izvestia on December 27, 1995, based on materials from a roundtable discussion, many businessmen in Russia previously held various government positions. More than three-quarters of experts believe that the "new rich" built their fortunes with powerful patrons. Two-thirds of experts believe that the wealthy acquired their wealth with the support of high-ranking friends. The overwhelming majority of experts believe that only a very small number of people earned their wealth through hard work. According to data from the Russian Academy of Sciences, in 1997, 61% of business elite representatives held government positions in the former Soviet Union, occupying various positions at various levels of government.

In China, the "new rich" class also accumulated wealth, to varying degrees, with the support of the government. From 1998 to 2003, the Chinese government conducted investigations at the provincial and national levels into the activities of officials who violated the law and discipline. According to data obtained by the Central Commission for Discipline [of Civil Servants] over a six-year period at the provincial and national levels, out of 109 cases of discipline and law violations, 74 violations were noted in the economic sphere, accounting for 67.9% [of all cases of discipline violations by officials]. Within the economic violations, 36 of them were related to the activities of private enterprises, accounting for 48.65%. 27 cases related to the participation of 23 private enterprises were referred to the courts, accounting for 85.2%.

4. Social assessments of the Chinese and Russian "new rich" class are not high.

In general, whether it's Russia or China, the "new rich" have a bad reputation, they are criticized more than praised, and there are more negative assessments than positive ones.

In Russia, the class of "newly rich" that emerged during social transformations has been popularly nicknamed "new Russians." In 1997, at a roundtable discussion organized by the magazine "Russian Observer," Russian scholars and experts noted that the "newly rich" class in Russia is generally not distinguished by high moral character. Instead, they are noted for their cunning, unscrupulousness, selfishness, and cruelty. At the same time, [it is necessary to note] the determination, will, and energy of this social group. The following definition might be appropriate for the Russian class of "newly rich": the market is the use of bad habits to achieve good goals. Researcher A. Kim, who participated in the discussion of this topic, noted that the "new Russians" lack a sense of social responsibility... and without it, it is impossible to talk about building harmonious social relations.

According to the Center for Social Research of the University of China, [only] 5.3% of respondents believe that most of China's "new rich" have acquired their wealth legally, 14.5% believe that the rich have made their fortunes "more or less" honestly, 48.5% of respondents believe that there are social channels that allow one to acquire wealth honestly, 10.78% of respondents believe that there are "almost no" such channels, and at the same time, according to another study, 29.7% of respondents believe that the emergence of this new class has more negative consequences [for society] than positive ones, and 24.6% of respondents believe that the role of the "new rich" class is more positive than negative.

Second: an analysis of the reasons and characteristics of the differences between the “new rich” class in China and Russia.

1. The Chinese and Russian classes of “new rich” differ in their level of education and level of culture.

In Russia, the overall level of education among the "newly rich" class is high, while in China, the overall quality of education is unevenly distributed due to varying levels of access to educational opportunities. This is because conditions were different at the initial stage of the transition: the Soviet Union was more urbanized, with the rural population accounting for only 34% of the total, while in China, 80% of the population was concentrated in rural areas. In the former Soviet Union, the social security system covered both urban and rural areas, while in China, social security was limited to urban areas, and in the vast majority of rural areas, social security was virtually nonexistent, which, to a certain extent, impacted the overall quality of life. Moreover, with the reforms that began to bring the economies of rural regions and cities closer together and began to transform society, the number of people seeking to achieve wealth by any means necessary increased sharply: through migration to cities, even with the prospect of initially becoming unemployed in the city, through self-employment, or through participation in the farmers' movement—all of this [far from] contributing to the rise of such people's cultural level. Just as the process of socioeconomic transformation initially failed to contribute to this, creating a cultural gap with the social group of high-tech enterprise workers and educated party and government officials, requiring the opening of colleges and universities for the most far-sighted private entrepreneurs. This will gradually influence the adjustment of the knowledge level of the "new rich" class. However, the aforementioned unevenness [in the level and quality of education] still remains. Russia is one of the leaders in the eradication of illiteracy; over the past 15 years, 91,100,000 people have received secondary education, which is 73.9% of the total number of citizens, 16% have a university education, and even during the Soviet Union, before the radical reforms, the country was led by party and government officials, directors of large enterprises, who had a very high level of culture and education, [well, if] we take, for example, members of the "seven bankers" - businessman Gusinsky was [in Soviet times] a theater director, Berezovsky was a mathematician and a corresponding member of the USSR Academy of Sciences...

2. The class of "new rich" in China and Russia influences economic life to varying degrees.

1) Differences in wealth.

It's quite difficult to determine the level of wealth of citizens who could be classified as "newly rich," as both in China and Russia, the wealthy are reluctant to publicize the size of their real assets. Furthermore, even within a single country, wealth standards vary at different times and across different regions. However, by examining available data on accumulated personal wealth and assets in China and Russia, comparisons can still be made. From 1991 to the present day, the "new rich" in Russia have accumulated fortunes in the tens of billions of dollars, for example, M. Khodorkovsky's fortune before the court verdict reached $150 billion, and since 1978, after 27 years [of reform policy implementation], very rich people have also appeared in China, for example, according to the weekly magazine "Fortune" of June 27, 2005, published in the article "list of 500 richest people" for 2005, the fortune of these rich citizens amounted to 1.19 billion yuan, and the number one businessman on the list, Chen, had a personal fortune of [only] 150 billion yuan or about $1.80 billion. These data indicate that during the transition period in Russia, the class of "new rich" has accumulated significantly greater fortunes than in China, and its representatives may well join the world class of rich people.

2) The rate of wealth accumulation within the Chinese and Russian “new rich” classes differs.

Based on the above analysis, we can conclude that large amounts of capital were accumulated in Russia much faster than in China.

According to Forbes magazine, just a few years ago, there were no Russian citizens on the list of the richest, but by 2003, 17 were listed, slightly fewer than the US, Germany, and Japan. And by May 2004, according to the same magazine, Russia had risen to second place after the US in the number of dollar billionaires. This was somewhat surprising to researchers. In comparison, the fortunes accumulated by China's wealthiest citizens pale in comparison, and none of them can yet be considered part of the global business elite.

3) Differences in the degree of influence on economic life.

During the transition period in Russia, a new social stratum emerged, led [in the 1990s] by representatives of the "seven bankers," and representatives of the seven largest financial consortiums continue to exert significant influence on economic and political life. These seven largest financial consortiums, possessing a large number of subsidiaries and holdings, and owning controlling stakes in many joint-stock companies with over 10,000 employees, have extended the "tentacles" of their influence into all spheres of social life—politics, the economy, and the social sphere—possessing sufficient energy to influence the functioning of the national economy as a whole. In October 1996, assessing the influence of Berezovsky's then-largest financial conglomerate, the Financial Times reported that six financial groups had brought up to 50% of the Russian economy and most of the media under their control, and all had their own [powerful] banking structures. In China, the potential for the “new rich” class to influence the national economy is much more modest; this influence may only have an impact on the economy in the long term.

The main differences between the "new rich" classes in China and Russia that arose during the transformation:

1) China and Russia chose different paths to transformation: while China opted for gradual reforms, Russia for radical ones. 2) Because China opted for gradual reforms, its leadership was able to constantly monitor the progress of change, regulating legislation, identifying and correcting errors, and thereby reducing the costs of transition. In Russia, the "new rich" gained superadvantages due to the imperfections of the political and legal system. 3) The transformation process had different goals. The goal of the transformation in China was initially to eliminate social inequality and exploitation, and to achieve social prosperity. Therefore, the Chinese leadership constantly implemented a number of measures to reduce the income gap between the richest and poorest strata of the population, improve social security, and punish corrupt officials. This is precisely why the "new rich" class in China does not wield as much influence as in Russia, where capital was formed [largely] within the framework of shadow structures.

3. Analysis of the influence of the Chinese and Russian "new rich" class on political life.

Gaining economic power during the transition period, the "newly rich" class is obliged to put forward its own political demands in order to more actively participate in political life and strive to realize its rights and interests. However, in both countries, the new class's political participation has evolved differently. According to research, representatives of the "newly rich" class in China have long maintained a political wait-and-see attitude, fearing that a radical shift in state policy could once again lead them to be viewed as "bourgeois elements" and subject them to political persecution. Only with the deepening of reform and opening-up policies did their doubts begin to dissipate. Consequently, the "newly rich" class in China gradually began to formulate its own political aspirations, which manifest themselves in two types of actions: first, legitimate actions related to calls for establishing connections with state structures that would allow Chinese businesses to convey their reasonable demands and proposals to the authorities through official channels, as well as opportunities to participate in party activities and resolve disputes; second, illegitimate actions related to corruption and bribery, which poison political life. However, overall, the "newly rich" class in China has not yet formed a unified political aspiration.

In Russia, the influence of the "newly rich" class on the political life of society is significantly greater than in China, and it is characterized by the presence of unified political aspirations. The power of capital in Russia is quite significant, as demonstrated, for example, in the 1996 presidential elections, when a situation arose in which a conglomerate of leading Russian businessmen formed a united front against the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, providing solid support to Yeltsin. This fact demonstrates not so much the political victory of big Russian business as the growing political influence of business circles. In June 1998, in order to avert the looming economic crisis, Boris Yeltsin relied on negotiations with big business, and thus, according to the Washington Post, a "shadow cabinet" was effectively formed on the basis of the Advisory Committee on Economic Policy [to the Russian government]. It's also worth recalling the political scandal initiated by Berezovsky, which resulted in Yevgeny Primakov being forced to leave the government in 1999. All these facts indicate that the "new rich" class in Russia possesses political energy to a degree that allows it to influence political life.

What is the essence of the differences in the influence of the Russian and Chinese "new rich" classes on the political life of society? I believe the main reasons are the following: 1) As we noted in the first part of our analysis, despite some common features of the formation of the "new rich" class in China and Russia, its relations with the government are structured differently in our countries. This is due to the different political experience of its representatives. In Russia, representatives of the business elite already had significant political experience by the time the reforms began, having held leadership positions in government agencies and enterprises. According to research by the Russian Academy of Sciences, 61% of representatives of the Russian business elite held leadership positions in the Soviet state apparatus. For example, Chernomyrdin served as Minister of Oil and Gas during the Soviet Union, and Khodorkovsky was a Komsomol functionary. In China, the "new rich" class has little or no experience participating in political life. 2) In implementing radical reforms, Russia, unlike China, chose the Western model of parliamentary democracy, which allowed the "newly rich" class to take a more active part in the country's political life and create a favorable political atmosphere. 3) There are significant socio-psychological differences between our two countries in the models of [political] behavior of businessmen. The Chinese "newly rich" class is still under the influence of the "Cultural Revolution," so some of its representatives still fear that the reforms may be rolled back and they will again be called "bourgeoisie," calling into question the legal protection of private property. This is one of the reasons why the "newly rich" are in no hurry to flaunt their wealth [by actively participating in political life], with the exception of cases of tax evasion, the origins of which lie in the mentality of the Chinese people, the formation of which was seriously influenced by the times of the "Cultural Revolution." In Russia, there are no fears about the possibility of a return to the times of the Soviet Union, so representatives of the "new rich" class do not have concerns similar to those mentioned above, and they actively participate in political life, maximizing their usefulness.

Third: a comparison of the “new rich” classes in China and Russia.

A comparative analysis of the “new rich” classes in China and Russia during the transition period yielded the following results.

First of all, it's important to note the abstract nature of general discussions about the radical nature of transformation or the positive and negative aspects of a given political regime. In reality, it's far more important to consider national conditions, national characteristics, and real facts, rather than blindly copying certain [universal] development models. The progressiveness of any regime is determined by its capabilities, including, if necessary, the ability to take radical measures to reduce the costs of transition and the costs associated with the destabilization of social life. In other words, the choice of a specific reform model depends on local conditions and the potential for successfully achieving the stated goals of transformation.

During the transition, Russia ignored its specific national characteristics, historical, and cultural traditions, copying the Western development model. This created additional difficulties during the transition period, as noted in a growing number of scholarly articles on the topic. Russian leaders recognized that blindly copying development models from foreign textbooks would only increase the costs of transition and alter attitudes toward the need for reform. Russia's revival based on market and democratic principles, while borrowing from positive experience, is entirely possible, but only with a rational approach to implementing this experience. Adherence to this requirement is essential to ensuring social stability and improving living standards. Guided by this pragmatic idea, the Russian government has achieved much in the modern world in recent years. To what extent are the Chinese adhering to this principle in their reforms? This question deserves separate and careful consideration.

Second, as China deepens reforms, it must learn from Russia's experience to avoid the costs of numerous mistakes, such as sweeping privatizations, mass bankruptcies, a hodgepodge of laws, and rising transition costs.

An important lesson for China is the state-owned enterprise reform, which led to the loss of a large share of state-owned assets in Russia. Therefore, special attention should be paid to reforming state-owned enterprises without losing their assets, as demonstrated, for example, by the establishment of the State Supervision and Administration Commission for State-Owned Enterprise Reform on March 24, 2003. Despite some successes in its work, many unresolved issues remain in the supervision and management of assets in a number of provinces and counties, where oversight remains weak, leading local authorities to engage in covert manipulation of state property. This requires increased vigilance in strengthening law and order and avoiding a repeat of the mistakes made in Russia.

Third, China should learn from Russia's experience to improve laws and regulations governing the activities of the new rich and to create the opportunity to build a harmonious society with socially responsible businesses.

Since B. Yeltsin counted on the help and support of the class of the "new rich", a policy of indulgence and compromise was pursued during his time, which led to the possibility of free political manipulation [carried out] by some representatives of this class. After V. Putin came to power, a number of radical measures were taken to limit the encroachment of representatives of this class on omnipotence, the oligarchs found themselves outside of politics, which created favorable opportunities for the development of the relationship between political stability and economic growth.

Representatives of China's "newly rich" class are attempting to participate in political life in two ways: first, having accumulated vast fortunes and gained control of a portion of the financial sector, they have begun attempting to bribe officials and are also attempting to control local political life. Therefore, heeding the lessons of the Yeltsin era, it is essential to firmly adhere to the principle of purity of ranks. At the same time, while taking reasonable political demands into account, we must encourage their advancement. This, ultimately, should lead to the elimination of exploitation and differentiation, and to the triumph of the cause of universal prosperity for socialism with Chinese characteristics, more effective social distribution, the development of social responsibility among the wealthy class, the creation of conditions for a harmonious society, and the development of a socialist political civilization with Chinese characteristics. The "newly rich," while earning large sums of money, must also share political responsibility, as the further development of the socialist market economic model within which they grew up depends on them. Furthermore, China's leadership must continue to improve laws and regulations, creating conditions for the development of a healthy "new rich" class.

Fourth, compared to Russia, even during the transition period, and especially compared to the West, China remains a relatively modest country with a huge population of 1.3 billion. Therefore, we need to develop legitimate businesses, businesses created through honest work, to preserve the socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics. However, we cannot rely on one-sided assessments of the "newly rich" class, focusing solely on negative assessments of their activities. We must carefully evaluate the activities of this class based on an analysis of specific historical conditions, taking into account the transition period, and encouraging legitimate entrepreneurial activity.

Fifth, during the transition period, calls for the immediate closure of the gap between rich and poor are tantamount to demands for the demolition of the wall [of misunderstanding] between West and East, since changes of this kind require altering the social structure, improving social relations as a whole. Achieving this goal requires efforts to organize the shared use of reform results by all social strata.

Xu Yuangong

https://prorivists.org/inf_theorychina-russia/

Google Translator