Breaking the Influence of International Capital in Africa

Posted by INTERNATIONALIST 360° on SEPTEMBER 28, 2022

ROAPE interviews the Ruth First prize winner Japhace Poncian about the crippling influence of international capital on the continent, resource nationalism, and the need for Africa to break its dependence from foreign direct investment and technology and to harness its own resources. Japhace argues that Africa must build up its own technical, financial, and human capacities to master its own fate.

ROAPE interviews the Ruth First prize winner Japhace Poncian about the crippling influence of international capital on the continent, resource nationalism, and the need for Africa to break its dependence from foreign direct investment and technology and to harness its own resources. Japhace argues that Africa must build up its own technical, financial, and human capacities to master its own fate.

ROAPE: Can you please tell us, Japhace, about yourself, and your background?

Japhace Poncian: I was born and grew up in a rural village in northwestern Tanzania. I had all my primary and ordinary secondary education there before going for my Advanced level secondary education. After my A-level education, I joined Mkwawa University College of Education, which is a constituent college of the University of Dar es Salaam for my BA (Education) degree in 2006, majoring in History and Geography. Right from my ordinary secondary education, history had always fascinated me. I was always fascinated by leftist perspectives on Africa’s marginalization in the international political economic system. After my BA degree, I was recruited as a Tutorial Assistant of History at Mkwawa University College of Education, which is a constituent college of the University of Dar es Salaam.

From Dar, I went for an MA in Global Development and Africa at the University of Leeds, United Kingdom to further my intellectual curiosity about Africa’s place and role in global political economy. Taught and supervised by the likes of Raymond Bush, I slowly developed interest in the political economy of extractive resources. I subsequently wrote my MA dissertation on Tanzania’s then mining law which was enacted in 2010. I problematized the content of the resulting law in light of the then public and political outcry about the infamous neoliberal reforms that had characterized the mining sector since the mid-1990s. Building on this background, I moved to Australia for my PhD at the University of Newcastle in 2015 where I researched the government-community engagement dynamics in the governance of Tanzania’s natural gas.

A common strand running through my research was my focus on how extractive resource politics impact unfairly on the communities, how these communities organize to fight back, how the state responds and what this means for the broader processes and national and international political economy of resources. I have continued to work along these lines but have extended my research into resource nationalist politics which my recent ROAPE paper draws. Apart from this research, I also teach undergraduate courses in Development Studies and Political Science at Mkwawa University College of Education.

Tanzania was the ‘incubator’ of ROAPE in our early days (with comrades like Issa Shivji involved from the start). Before ROAPE was founded, many of our comrades were inspired and schooled in Nyerere’s Tanzania. There was much continental hope for radical and socialist changes from Dar es Salaam in the 1960s and 1970s. Coming from a later generation, can you tell us about what it was like growing up in the context of this history and environment and how it has influenced you, your family and your work?

I must say from the outset that growing up in this context was inspirational. Even though I did all my schooling in the post-socialist era, the memory of Nyerere’s socialist policies were still very much intact and commanding public support. Some policy practices of the socialist era were still being practiced at the time. I remember we used to study for free and were usually provided with free exercise books and school equipment at the beginning of each year until around 1994 when this practice was abandoned. Yet socialist ideas continued to be at the core of our primary school songs.

Even though President Mwinyi [Ali Hassan Mwinyi was the second president of Tanzania from 1985-1995] was the presiding leader, the general community in which we lived and interacted still held Nyerere in high esteem. The national radio broadcasting, Radio Tanzania Dar es Salaam, used to broadcast Nyerere speeches every day after the 8pm news bulletin. Being the only radio station at the time, this meant that the ideas we were exposed to were mostly those of Nyerere. So, growing up in this context influenced my future perspective about development and the international system. So, it is not surprising that even when I went for my secondary education, I gravitated to Africa’s history from what we used to call back then an Afro-centric perspective. This also explains why I have continued to conduct my research building on the legacy and heritage of Nyerere’s socialist policies.

Your own research has looked at the much spoken about ‘resource nationalism’ in Tanzania in recent years – there was an expectation, or at least political hope, that this was a radical measure that would take back for the country’s poor its own wealth and resources. Can you describe the political context of these measures, and what has really been revealed (and achieved) by such politics?

Resource nationalism, as I and other scholars such as Thabit Jacob have argued is very much a product of failed resource liberalism. When it was adopted during the late 1980s and early to mid-1990s, resource liberalism was premised on the ‘false’ promise of job opportunities, revenues, FDI inflows and technological exchange. However, the reality what actually came about did not come anywhere near what was promised.

Across Tanzania and the rest of Africa, there was public outcry at the failure of these reforms and the need for Tanzania to take measures to address the imbalance. At the same time, opposition parties, themselves a product of political liberalization, were gaining political mileage as they built on popular dissatisfaction to galvanise popular support. From 2005 to 2010, it was becoming clear that if nothing was done, the ruling party Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM) would lose many parliamentary seats to the opposition and would perform poorly in presidential elections. This being the case, the CCM government under President Kikwete (2005-2015) built on the Nyerere on international capital and its plundering tendencies to re-introduce resource nationalism to tame the growing influence and popularity of opposition parties.

The opposition Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (CHADEMA- Party for Democracy and Development), for instance, had organized popular campaigns dubbed ‘operation sangara’ and Movement for Change (M4C)’ in the period between 2007 and 2013. Riding high on corruption scandals and mining failure to deliver benefits to Tanzania, CHADEMA went throughout the country mobilizing the youth and poor to the extent it was became a thorn in the side of CCM. Opposition members of parliament also became very vocal in parliament so that some top political leaders including the Prime Minister were forced to resign on account of corruption.

Together these crises pushed the government to come up with ‘resource nationalist measures’ between 2006 and 2010 and subsequently in 2015 and 2017. The CCM has held onto power, but these measures have not helped increase its electoral performance. Further, resource nationalism has not transformed the extractive sector into one that bolsters value addition and industrialisation.

Though there have been some gains due to subscription to the Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) these cannot be attributed to resource nationalism. Finally, the reforms have made the sector unstable and unpredictable because they have meant that periodic revisions have become a norm. The 2017 nationalist reforms, for instance, are now being sidelined by the sitting government in favour of the market.

If, as you claim in your Ruth First prize winning article, the key element in Tanzanian political economy are ‘structural constraints’, which has undermined efforts at radical reforms, what can be done to alter and transform the continents trajectory?

You are very right on structural constraints in relation to Tanzania’s efforts to alter and transform its trajectory. Resource nationalism, and indeed broader economic nationalization programmes, has historically been adopted in Tanzania and across Africa within the constraints of structural challenges. Tanzania and Africa generally, has historically sought to fight the power of international capital by resorting to nationalistic policies and strategies without addressing the structural constraints secure capital’s control over nation-states.

Whereas resource nationalist reforms adopted recently and those adopted during the Arusha Declaration era had good intentions and represented a government’s resolve to address the negative consequences of international capital encroachment, they nevertheless were ill-thought and failed.

Looking forward, I would suggest that Africa should place more emphasis on transforming the structural constraints first before introducing radical resource nationalist measures. You do not break from the influence of the international capital if you still depend on foreign direct investment and technology to harness your resources. It would make sense, and many have written about this, for Tanzania and Africa to invest in building its technical, financial and human capacity if the goal is to take over the running of the extractive sector. Without investing in building this capacity, resource nationalist policies on, for instance, state participation, local content, resource-based industrialisation, etc. cannot produce the desired outcomes by continuing to depend on international capital. If anything, Africa should start building from below before it can flex its ‘weak’ muscles against the politically, economically and technologically powerful multinational corporations. Because this appears to be a longer term strategy whose ‘fruits’ can only be realised after a long time, Africa can pursue this while at the same time continue to negotiate fair deals with international capital without initially signaling a ‘threat of nationalisation.’

What role does agency, and the engagement of working people, play in the transformation of Tanzania? There have been some important struggles in Tanzania in recent years, can you talk about this?

Agency is a very important determinant here. In fact, none of the three waves of resource nationalist reforms in Tanzania have come without such agency. Much of the reforms have been enacted in response to political and general public outcry, often with the ruling party feeling politically threatened. Struggles from within the ruling party (i.e., between party cadres loyal to the ideas of Nyerere and those ascribing to market forces), confrontation between artisanal and small scale miners and large scale miners, community complaints, civil society advocacy and popular campaigns building on the emotions of the public have all been very important in bringing about then reforms in the form of resource nationalism.

Everyone from ruling party policy makers to the common citizen has complained about Tanzania not benefitting adequately from extractive resource extraction and demanded that the government take steps to address this. Although the agency and struggles of the popular classes have been important in shaping Tanzania’s extractive reforms, the processes through which these reforms have been instituted has tended to be exclusionary. The government has consistently sought to introduce legal reforms under a certificate of urgency, systematically keeping alternative and popular voices and influence away from the process.

In effect, many of these reforms have tended to be contentious and controversial resulting in their revision within a short period of time. Therefore, one can say that civil society agency and public dissatisfaction have always pushed the government to introduce reforms. However, the government has consistently hijacked the agenda by legislating for reforms behind ‘closed’ doors. Unquestionably this is why we have not seen that much transformation coming out of these reforms.

Looking at the continent as a whole, and similar rhetoric at industrialisation (see Ethiopia and Rwanda for example), how do you interpret and understand efforts at development on the continent and the role of imperialism and structural constraints in undermining these efforts?

On a general note, it appears that Africa has awakened from slumber and is keen to take advantage of its resources to catapult socio-economic and industrial transformation. In the period since, say, the first half of the 2000s, certain African politicians have individually and collectively made at least a rhetorical commitment to large scale transformation. Mega-infrastructural, energy and industrial projects have become fashionable across the continent. The adoption the Africa Mining Vision in 2009 has reinvigorated Africa’s desire to promote a resource-based industrialisation. Similarly, the adoption of the African Continental Free Trade Area is an attempt to address intra-African trade barriers to ensure African countries trade amongst each other to promote continental industrialisation. The global fourth industrial revolution is also exerting pressure on the continent with countries striving to cope with and take advantage of its trends for their own transformation.

On more practical level, however, these efforts are not only beset by global imperial and structural constraints but are also challenged by the nationalist orientation of individual African countries. The development challenges that Africa face today require deep partnerships to address them; yet this continental collaboration and partnership does not seem to take root. Xenophobic attacks in some countries point to the deeper intra-African structural constraints and unresolved legacies of colonial imperialism.

Further, the sluggish implementation of continentally agreed strategies by individual countries is suggestive of the lack of a Pan-African spirit needed to overcome imperialist challenges. What do you expect if, for instance, African leaders voluntarily agreed and adopted a continental Mining Vision in 2009 but none of them has fully, or in any real sense, implemented the Vision which is now more than ten years old? How can mining bolster industrialisation if resource-rich countries do not respect the decisions they made on their own volition without external influence?

How do you see your work and research, and political engagement, evolving in the coming years? What areas are you planning to move into?

Looking into the future, I still see myself working and researching on political-economic questions regarding mineral, oil and gas resource extraction and development dynamics. My particular interest is to further pursue a line of inquiry on grassroot community organising and movements that seek to challenge the mainstream resource extraction agenda and how ‘resource governance’ seeks to integrate their voices and concerns into policy and practice, which as we have seen does little or nothing. A second line of inquiry that I am interested in is renewable energy politics in Africa in the context of global sustainability initiatives and targets and regional and local development needs and dynamics.

Japhace is a lecturer in Development Studies and runs the Department of History, Political Science and Development Studies at Mkwawa University College of Education in Tanzania. He researches on the politics of extractive resource governance and broader development issues in Tanzania and Africa. He holds a PhD in Politics from the University of Newcastle in Australia, an MA (Global Development and Africa) from the University of Leeds, in the UK, and a BA (Education) from University of Dar es Salaam.

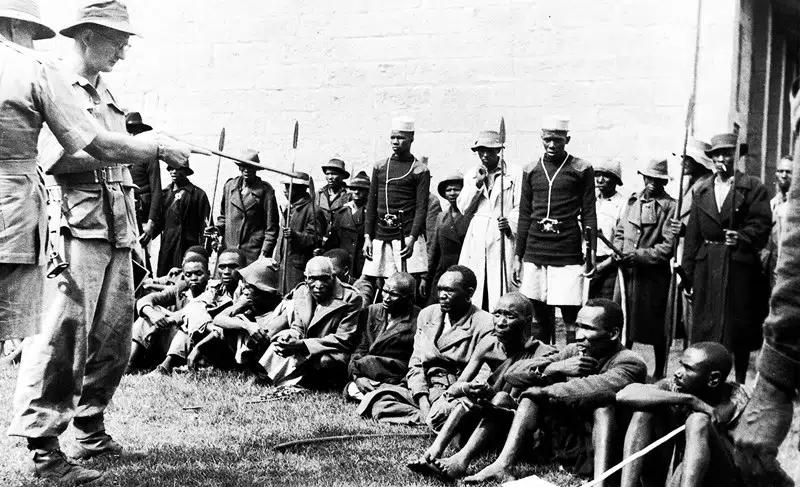

Featured Photograph: Miners in Tanzania (23 August 2017).

https://libya360.wordpress.com/2022/09/ ... in-africa/

Western Sahara: Africa’s Last Colony

Posted by INTERNATIONALIST 360° on SEPTEMBER 28, 2022

Meriem Naïli

Meriem Naïli writes about the continuing struggle for the independence of Western Sahara. Occupied by Morocco since the 1970s, in contravention of the International Court of Justice and the UN. The internationally recognised liberation movement, POLISARIO, has fought and campaigned for independence since the early 1970s. Naïli explains what is going on, and the legal efforts to secure the country’s freedom.

Meriem Naïli writes about the continuing struggle for the independence of Western Sahara. Occupied by Morocco since the 1970s, in contravention of the International Court of Justice and the UN. The internationally recognised liberation movement, POLISARIO, has fought and campaigned for independence since the early 1970s. Naïli explains what is going on, and the legal efforts to secure the country’s freedom.

The conflict over Western Sahara can be described as a conflict over self-determination that has been frozen in the past three decades. Western Sahara is a territory in North-West Africa, bordered by Morocco in the north, Algeria and Mauritania in the east and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. A former Spanish colony, it has been listed by the UN since 1963 as one of the 17 remaining non-self-governing territories, but the only such territory without a registered administrating power.

Since becoming independent from France in 1956, Morocco has claimed sovereignty over Western Sahara and has since the late 1970s formally annexed around 80% of its territory, over which it exercises de facto control in contravention of the conclusions reached by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in its advisory opinion of October 15, 1975, on this matter. The court indeed did not find any “legal ties of such a nature as might affect the application of resolution 1514 (XV) in the decolonization of Western Sahara and, in particular, of the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory” (Western Sahara (1975), Advisory Opinion, I.C.J. Reports 1975, p.12).

On 14 November 1975, the Madrid Accords – formally the Declaration of Principles on Western Sahara – were signed between Spain, Morocco, and Mauritania setting the conditions under which Spain would withdraw from the territory and divide its administration between the two African states. Its paragraph two reads that “Spain shall immediately proceed to establish a temporary administration in the territory, in which Morocco and Mauritania shall participate in collaboration with the Jemâa [a tribal assembly established by Spain in May 1967 to serve as a local consultative link with the colonial administration], and to which the responsibilities and powers referred to in the preceding paragraph shall be transferred.”

Although it was never published on the Boletin Oficial del Estado [the official State journal where decrees and orders are published on a weekly basis], the accord was executed, and Mauritania and Morocco subsequently partitioned the territory in April 1976. Protocols to the Madrid Accords also allowed for the transfer of the Bou Craa phosphate mine and its infrastructure and for Spain to continue its involvement in the coastal fisheries.

Yet in Paragraph 6 of his 2002 advisory opinion, UN Deputy Secretary General Hans Corell, reaffirmed that the 1975 Madrid Agreement between Spain, Morocco, and Mauritania “did not transfer sovereignty over the Territory, nor did it confer upon any of the signatories the status of an administering Power, a status which Spain alone could not have unilaterally transferred.”

The war

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Rio de Oro (POLISARIO) is the internationally recognised national liberation movement representing the indigenous people of Western Sahara. Through the self-proclaimed Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), it has been campaigning since its creation in May 1973 in favour of independence from Spain through a referendum on self-determination to be supervised by the UN. A war broke out shortly after Morocco and Mauritania’s invasion in November 1975. Spain officially withdrew from the territory on 26 February 1976 and the Sahrawi leadership proclaimed the establishment of the SADR the following day.

In 1984, the SADR was admitted as a full member of the Organisation of African Unity (now the African Union), resulting in Morocco’s decision to withdraw the same year in protest. Morocco would only (re)join the African Union (AU) in 2017. The admission of the SADR to the OAU consolidated the movement in favour of its recognition internationally, with 84 UN member states officially recognising the SADR.

In the meantime, to strengthen its colonization of the territory, Morocco had begun building what it later called “le mur de défense” (the defence wall). In August 1980, following the withdrawal of Mauritanian troops the previous year, Morocco sought to “secure” a part of the territory that Mauritania had occupied. Construction of the wall – or “berm” – was completed in 1987 with an eventual overall length of just under 2,500km.

A “coordination mission” was established in 1985 by the UN and the OAU with representatives dispatched to find a solution to the conflict between the two parties. After consultations, the joint OAU-UN mission drew up a proposal for settlement accepted by the two parties on 30 August 1988 and would later be detailed in the United Nations Secretary General’s (UNSG) report of 18 June 1990 and the UN Security Council (UNSC) resolution establishing United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO).

Since 1979 and the surrender of Mauritania, around 80% of the territory has remained under Morocco’s military and administrative occupation.

Deployment of MINURSO

The Settlement Plan agreed to in principle between Morocco and POLISARIO in August 1988 was submitted to the UNSC on 12 July 1989 and approved in 1990. On 29 April 1991, the UNSC established MINURSO in resolution 690, the terms of reference for it being set out in the UNSG’s report of 19 April 1991. The plan provided for a cease-fire, followed by the organisation of a referendum of self-determination for which the people of Western Sahara had to choose between two options: integration with Morocco or plain and simple independence.

In this regard, it provided for the creation of an Identification Commission to resolve the issue of the eligibility ofSahrawi voters for the referendum, an issue which has since generated a great deal of tension between the two parties. A Technical Commission was created by mid-1989 to implement the Plan, with a schedule based on several phases and a deployment of UN observers following the proclamation of a ceasefire.

Talks quickly began to draw up a voters list amid great differences between the parties. POLISARIO maintained that the Spanish census of 1974 was the only valid basis, with 66,925 eligible adult electors, while Morocco demanded inclusion of all the inhabitants who, as settlers, continued to populate the occupied part of the territory as well as people from southern Morocco. It was decided that the 1974 Spanish census would serve as a basis, and the parties were to propose voters for inclusion on the grounds that they were omitted from the 1974 census.

In 1991, the first list was published with around 86,000 voters. However, the process of identifying voters would be obstructed in later years, mainly by Morocco which attempted to include as many Moroccan settlers as possible. The criteria for eligibility had sometimes been modified to accommodate Morocco’s demands and concerns. Up to 180,000 applications had been filed on the part of the Kingdom, the majority of which had been rejected by the UN Commission as they did not satisfy the criteria for eligibility.

Consequently, the proclamation of “D-Day”, to mark the beginning of a twelve-week transition period following the cease-fire leading to the referendum on self-determination, kept being postponed and eventually was never declared.

The impasse

Following the rejection by Morocco of the Peace Plan for Self-Determination of the People of Western Sahara (known as Baker Plan II) and the complete suspension of UN referendum preparation activities in 2003, Morocco’s proposal for autonomy of the territory under its sovereignty in 2007 crystallised the stalemate [the Peace Plan is contained in Annex II of UNSG report S/2003/565, and available here].

The Baker Plan II had envisioned a four or five-year transitional power-sharing period between an autonomous Western Sahara Authority and the Moroccan state before the organisation of a self-determination referendum during which the entire population of the territory could vote for the status of the territory – including an option for independence. It was ‘supported’ by the UNSC in resolution S/RES/1495 and reluctantly accepted by POLISARIO but rejected by Morocco.

The absence of human rights monitoring prerogatives for MINURSO has emerged as an issue for the people of Western Sahara as a result of the stalemate in the referendum process in the last two decades. MINURSO is the only post-Cold War peacekeeping operation to be deprived of such prerogatives.

Amongst the four operations currently deployed that are totally deprived of human rights monitoring components (UNFICYP in Northern Cyprus, UNIFIL in Lebanon, UNDOF in the Israeli-Syrian sector and MINURSO), MINURSO stands out as not having attained its purpose through the organisation of a referendum. In addition, among the missions that did organise referendums (namely UNTAG in Namibia and UNAMET in East Timor), all had some sort of human rights oversight mechanism stemming from their mandates.

On 8 November 2010, a protest camp established by Sahrawis near Laayoune (capital of Western Sahara) was dismantled by the Moroccan police. The camp had been set up a month earlier in protest at the ongoing discrimination, poverty, and human rights abuses against Sahrawis. When dismantling the camp, gross human rights violations were reported – see reports by Fédération internationale des ligues des droits de l’Homme (2011) and Amnesty International (2010).

This episode revived the international community’s interest in Western Sahara and therefore strengthened the demand by Sahrawi activists to “extend the mandate of MINURSO to monitor human rights” (see Irene Fernández-Molina, “Protests under Occupation: The Spring inside Western Sahara” in Mediterranean Politics, 20:2 (2015): 235–254).

Such an extension was close to being achieved in April 2013, when an UNSC resolution draft penned by the US unprecedentedly incorporated this element, although it was eventually taken out. This failed venture remains to date the most serious attempt to add human rights monitoring mechanisms to MINURSO. Supporters of this amendment to the mandate are facing the opposition by Moroccan officials who hold that it is not the raison d’être of the mission, and it could jeopardize the negotiation process.

What’s going on now?

At the time of writing, the people of Western Sahara are yet to express the country’s right to self-determination through popular consultation or any other means agreed between the parties. The conflict therefore remains unresolved since the ceasefire and has mostly been described as “frozen” by observers.

On the ground, resistance from Sahrawi activists remain very much active. Despite the risks of arbitrary arrest, repression or even torture, the Sahrawi people living under occupation have organised themselves to ensure their voices are heard and violations are reported. Freedom House in 2021 have, yet again, in its yearly report, rated Western Sahara as one of the worst countries in the world with regards to political rights and civil liberties.

Despite a clear deterioration of the peace process over the decades, several factors have signalled a renewed interest in this protracted conflict among key actors and observers from the international community. A Special Envoy of the AU Council Chairperson for Western Sahara (Joaquim Alberto Chissano from Mozambique) was appointed by the Peace and Security Council in June 2014. This was followed by Morocco becoming a member of the AU in January 2017.

More recently, major events have begun to de-crystalise the status quo. The war resumed on 13 November 2020 following almost 30 years of ceasefire. Additionally, for the first time, a UN member state – the US – recognised Morocco’s claim to sovereignty over the territory. Former US President Trump’s declaration on 10 December 2020 to that effect was made less than a month after the resumption of armed conflict. It has not, however, been renounced by the current Biden administration. As this recognition secured Morocco’s support for Israel as per the Abrahamic Accords, reversing Donald Trump’s decision would have wider geopolitical repercussions.

In September 2021, the General Court of the European Union (GCEU) issued decisions invalidating fisheries and trade agreements between Morocco and the EU insofar as they extended to Western Sahara, rejecting Morocco’s sovereignty. This decision is the latest episode of a legal battle taking place before the European courts.

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), had previously reaffirmed the legal status of Western Sahara as a non-self-governing territory, set by the UN in 1963 following the last report transmitted by Spain – as Administering Power – on Spanish Sahara under Article 73 of the UN Charter. The Court rejected in December 2016 any claims of sovereignty by Morocco by restating the distinct statuses of both territories.

The last colony in Africa remains largely under occupation and the UN mission in place is still deprived of any kind of human rights monitoring. In the meantime, the Kingdom of Morocco has been trading away peace in the form of military accords and trade partnerships. This situation must end – with freedom, and sovereignty finally won by Western Sahara.

https://libya360.wordpress.com/2022/09/ ... st-colony/

*************

The home of the President of the People’s United Democratic Movement (PUDEMO), Mlungisi Makhanya, in Swaziland, was attacked in the early hours of 20 September 2022.

Residence of Swazi pro-democracy leader bombed by alleged state-sponsored hit-squad

Originally published: Peoples Dispatch on September 21, 2022 (more by Peoples Dispatch) | (Posted Sep 27, 2022)

In Swaziland’s eastern town of Siketi in the Lubombo region, an alleged state-sponsored hit-squad, bombed the residence of Mlungisi Makhanya, president of People’s United Democratic Movement (PUDEMO), after midnight at about 1 AM on September 20.

“Residents in neighboring houses heard gunshots. Then they saw armed men had climbed a wall fence [of Makhanya’s house] and were shooting at the electric cable. After the lights went out, they threw what seemed to be explosive grenades into his house,” Wandile Dludlu, Secretary General of PUDEMO, told Peoples Dispatch. When flames engulfed his house “they sped away in their cars.”

Makhanya, however, is safe. Two months ago in July, PUDEMO had received credible information that its president was going to be a target of assassination, Dludlu said. PUDEMO is one of the leading pro-democracy parties in the continent’s last absolute monarchy where all political parties are banned.

Makhanya had been moved to safety in neighboring South Africa, where several pro-democracy activists from Swaziland have been forced into exile or hiding by the regime of King Mswati III.

When asked if the police have registered any case, Makhanya replied, “Of course not.” He said,

It was them [who did it]. They don’t entertain cases that require them to investigate themselves, or even worse, to investigate the army soldiers.

In a statement after the bombing, PUDEMO said,

This attack comes in the backdrop of threats from Mswati’s traditional governor, Timothy Ginindza, to the effect that the regime has trained an arson squad whose sole purpose is to target and burn down the homes of leaders of the Mass Democratic Movement (MDM) and to assassinate them.

MDM is a coalition of more than a dozen pro-democracy political parties, student unions, trade unions, youth organizations, and other groups. Ginindza’s threat to such organizations, Dludlu said, has been caught in an “intercepted” cell phone conversation in which he was “discussing.. the plot to bomb properties belonging to political leaders,” according to Swaziland News.

PUDEMO maintains that this hit-squad is a direct result of Mswati’s order to the security forces to take an “eye for an eye,” as he threatened in his Police Day address on August 5. Dludu said that there has been a significant rise in “attacks on homes of leaders and activists, arrests, and clampdown on mass activities like protests” since this speech.

Leaders of other prominent pro-democracy parties, including the Communist Party of Swaziland (CPS), have also faced increased attacks and raids on their homes.

Many believe his threat is an incitement to exact revenge for the attacks on his properties last year. These attacks occurred during the broader anti-monarchist insurrection that followed the violent crackdown on unprecedented nationwide peaceful pro-democracy marches.

Amid the attacks on the businesses and industries he owns, the King had briefly fled the country, returning only after his army had put down the rebellion by killing over 70 people and arresting hundreds.

Nevertheless, strong anti-monarchist sentiments have not only prevailed within urban contexts, but has also taken root in villages, which until last year were presumed loyal to the King.

Despite intensifying repression by the security forces who have since grown increasingly nervous, protests have continued as a regular feature in this small landlocked country with a population of 1.2 million. Most of the Swazi economy is owned by the King and run to finance the royal indulgences, including palaces, a fleet of Rolls Royce cars, and private jets. The youth see the myriad businesses and industries owned by him as a prime target to attack.

In this context, the monarch’s call for security forces to take an “eye for an eye” appears to have translated into increasing attacks and arson on homes of pro-democracy activists.

PUDEMO has assured that “the president remains unshaken, defiant, and ready for the revolutionary task of fighting side by side with you in attaining the freedom and liberation of the country from royal rule.”

“The value we attach to our material possessions is ephemeral, but the value we attach to our noble struggle is permanent,” the party states.

PUDEMO and the pro-democracy movement in Swaziland also received international messages of solidarity.

the International Peoples Assembly (IPA) wrote in a statement:

We vehemently condemn this and all attacks, harassment and intimidation of the people of Swaziland by the monarchy as a blatant violation of basic human and political freedoms.

The IPA, comprising about 200 progressive organizations from across the world, has reiterated that “peoples’ sovereignty and democracy are core pillars of our work and must be defended from Western Sahara and Morocco to Swaziland!”

https://mronline.org/2022/09/27/residen ... hit-squad/

********************

Zambia’s debt crisis a warning for what looms ahead for Global South

Zambia is heading toward critical negotiations to restructure its mounting debts. The IMF has approved a $1.3 billion bailout plan for the country, which will impose cruel austerity measures on the Zambian people

September 22, 2022 by Tanupriya Singh

Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema meets with IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva. (Photo: @KGeorgieva/Twitter)

On September 6, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) unveiled a series of conditions attached to a $1.3 billion loan program for Zambia under an Extended Credit Facility (ECF). The 38-month bailout was announced on August 31 following talks between Zambia and its official creditors to restructure its external debts, which had soared to $17.3 billion by the end of 2021.

As Lusaka heads into these debt relief negotiations, the IMF is imposing brutal austerity measures on the people of Zambia, at least 60% of whom are already living in poverty.

“Zambia is dealing with the legacy of years of economic mismanagement, with an especially inefficient public investment drive,” read a statement by the IMF. Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva went on to add: “Zambia continues to face profound challenges reflected in high poverty levels and low growth. The ECF-supported programme aims to restore macroeconomic stability and foster higher, more resilient, and more inclusive growth.”

How exactly does the IMF intend on achieving these goals? Through a “large, front-loaded, and sustained fiscal consolidation” that will reform “regressive and wasteful subsidies” and reduce “excessive and poorly targeted public investment:”

“These are typical, vintage IMF conditions of austerity, which effectively means slowing down government expenditure in quite a drastic way, the brunt of which falls on the poor, on women, and the youth,” stated Dr. Grieve Chelwa, the director of research at the Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy at The New School in New York, USA, in an interview with Peoples Dispatch.

The blow caused by the IMF’s conditions will be swift, with the complete removal of fuel subsidies set to take place by the end of September. Implicit subsidies, including reduced excise on petrol and diesel and zero-rating them for Value Added Tax (VAT), which the government had introduced in 2021 to cushion against soaring inflation and the impact of the pandemic, will also be eliminated. Import duties will be reintroduced.

The Bank of Zambia has already stated that the move will cause a “nudge” in inflation.

Subsidy removal will lead to a rise in electricity tariffs, which will have a demonstrably greater impact on poor households. According to data from the World Bank, only 44.5% of Zambia’s population had access to electricity in 2020. The figure for rural areas was 14%.

The IMF has also taken aim at Zambia’s agricultural subsidies, especially the 20-year-old Farmer Input Support Programme (FISP), and intends to reduce the cost of subsidies to around 1% of the GDP by 2025. The new program will be implemented in the 2023-24 agricultural cycle. According to Chelwa, a million Zambians—or approximately 5% of the country’s population—rely on the subsidy program for maize. A majority of these people, who are responsible for growing the bulk of the country’s maize, are small-scale farmers.

To increase revenues, the IMF has directed the Zambian government to expand its VAT base. This includes a rollback on VAT exemptions on unprocessed foodstuffs, limiting them to “specific items that figure prominently in the food baskets of the poor.”

Between July and September, over 1.35 million Zambians were estimated to be experiencing severe food insecurity driven by high food prices and climate shocks. Out of the 91 districts analyzed, over 15% were facing crisis (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification Phase 3) levels of food insecurity. An additional 34 districts are projected to fall under these conditions between October 2022 and 2023.

In an attempt to somehow gloss over the gravity of these measures, the IMF pointed to a projected increase in social protection spending from 0.7% of the GDP in 2020 to 1.6% in 2025, as well as the government’s plans to hire additional staff in the health and education sectors. It also made references to several social safety programmes, including World Bank-supported social cash transfers (SCT), adding that the monthly benefit under the program had been increased from 90 to 110 kwacha ($5.75 to 7) in 2021.

“Overall, for low-income households, the benefits from increased social spending should outweigh the impact from the removal of fuel and electricity subsidies,” the IMF claimed.

“In dollar terms, the increase in monthly benefits is nothing, it is a pittance especially given the increases in fuel prices, electricity prices, and the VAT, which will take place as a result of the Fund’s conditions,” said Chelwa.

Importantly, he added, “social cash transfers are given to the ultra-poor. You have all these distinctions of people characterized as being moderately poor, working poor, ultra poor. However, these are effectively abstract and arbitrary distinctions in countries that are [on the whole] massively poor.”

Not only are taxes on labor income expected to rise in the medium term, Chelwa argued, the rate of this increase will be faster than the taxes on profits in both mining and non-mining sectors, large portions of which are under the control of private corporations, owing to the aggressive structural adjustment and privatization pushed by the IMF and the World Bank in the 1990s.

“These are essentially properties of global and Western capital, so they are going to be treated quite favorably when it comes to taxation. The extent of this favorable treatment in the IMF document is shocking. 70% of the burden of raising new taxes is going to be the VAT; 15% is going to be the corporate sector,” Chelwa said.

“You would think that the IMF would tell Zambia that it was time to tax the mining sector appropriately, but that is conspicuously absent from the document, and this is by design.”

Mining corporations have been given major concessions in recent years, and these have been balanced by drastic cuts to social spending. Meanwhile, by 2019, Zambia’s debt rose to 85% of its GDP. Conditions worsened dramatically with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and debt rose to 118% of the GDP.

In November 2020, even though it was able to secure a debt relief agreement with China, Zambia became the first African country to default on its external debt payments, after it was denied a request for a six month extension on the payment of $42.5 million in interest on eurobonds due in October. However, the crisis had been years in the making.

Debt accumulation in Zambia

After having had most of its debt waived under the IMF and World Bank’s Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative, Zambia began accumulating new debt in 2012.

“Like many poorer countries, Zambia began borrowing from international capital markets based on the advice of international financial institutions,” explained Chelwa. “We were told that the prospects looked good and that the forecasts for commodity prices were strong. It is important to keep in mind that most countries in the Global South are exporters of raw commodities. They told us to borrow, and we went out and took out bonds.”

However, Chelwa pointed to important problems inherent to these bond contracts: “We were borrowing to finance infrastructure projects and expecting to repay in a very short period of time. Returns on projects like bridges, highways, and hospitals can sometimes take decades, but we were expecting to pay back within a decade.”

Compounding the issue was the fact that the “commodity prices, upon which the forecasts were based, crashed and then we have COVID-19 and the climate crisis. Ten years later, the debt is unsustainable, and the way that the international financial architecture is set up, we have to pay no matter what.”

One route is that of the IMF, Chelwa explained further, “where you accept a programme hoping that it will get you into the good books of those you owe money to. However, in actuality this process is quite convoluted and it is not a foregone conclusion that having an IMF arrangement will ensure that creditors treat us better.”

After its initial default in 2020, the Zambian government, under former President Edgar Lungu, formally requested to restructure its debt under the G20 Common Framework in February 2021.

In December, Zambia, now led by incumbent President Hakainde Hichilema, secured a staff-level agreement with the IMF for a bailout of upto $1.4 billion. However, final approval by the IMF board was contingent on assurances that Zambia’s debt could be brought down to levels considered sustainable.

In June 2022, a creditor committee led by China and France was established to deliberate Zambia’s debt relief request under the Common Framework. In July, the creditors agreed to restructure the country’s debts, paving the way for the IMF bailout.

In its report on September 6, the IMF stated that Zambia was seeking debt relief of $8.4 billion between 2022 and 2025. According to Debt Justice, $8.4 billion accounts for 90% of payments to government and private lenders in this period. The organization has called for a permanent cancellation of debt payments, so that these are “not rolled over to the 2030s to fuel another debt crisis next decade.”

With restructuring talks set to begin, one major hurdle stands in the way—private lenders, chief among them BlackRock. The asset management giant is currently the largest owner of Zambia’s bonds, holding $220 million.

On September 16, over 100 leading economists and other experts from across the world wrote an open letter to BlackRock, the G20, and Zambia’s other creditors to engage in a “large-scale debt restructuring, including significant haircuts, in order to make Zambia’s debt sustainable.”

“Over the last decade of low global interest rates, private lenders charged high-interest loans to lower income countries. The supposed logic for charging poorer countries far higher interest rates than richer countries was the greater risk of economic shocks that could make debt repayment more difficult. That risk has now materialized,” the letter noted.

The rise of private lending and crisis profiteering

How is it that private lenders such as BlackRock rose to such prominence when it comes to the debt scenarios in poor countries?

The answer, as Chelwa explained, lies in a major change in the international financial architecture in the past decade or so. “Historically, most indebted countries have borrowed from other countries. It is bilateral debt, and it is coordinated under the framework of the Paris Club, which is essentially this list of wealthy creditor countries,” he stated.

“About 12-13 years ago, the situation changed because countries started getting what are called sovereign credit ratings, from agencies including Moody’s, Fitch, and Standard and Poor’s, after which they could borrow from private lenders. So these countries began to issue bonds. This was the structural change and now we are dealing with the first major crisis of this new architecture,” Chelwa added.

Between 2022 and 2028, 45% of Zambia’s external debt payments are to Western private lenders, 37% to public and private lenders in China, 10% to multilateral institutions, and 8% to other governments.

In 2020, BlackRock was among private lenders which refused to suspend Zambia’s debt payments. While the G20 declared that some bilateral debts would be waived under the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), private lenders and multilateral lenders were excluded from the measure. Not only that, private lenders were able to exploit the suspension of debt by official sources to extract full debt repayments.

Between 2021 and 2024, 59% of Zambia’s external debt payments were estimated to be to private creditors. According to Debt Justice, some private lenders stood to make profits between 75-250% from Zambia’s debt if paid in full. This is at a time when people are losing their lives and livelihoods under a deadly pandemic.

In April, Debt Justice estimated that BlackRock could make $180 million in profit for itself and its clients from its investment in Zambian bonds, if the debts were paid in full. This would represent a profit of 110%. Meanwhile, Zambia has cut its health and social protection spending by 20% in the past two years. A report by Oxfam released in May found that the government’s planned cuts between 2022-2026 would amount to more than five times the annual health budget.

The G20 Common Framework provides for coordinated debt relief, and mandates private creditors to participate on comparable terms. Since the start of 2021, three countries—Zambia, Chad, and Ethiopia—have applied for relief under the framework. No help has been given until now.

“The prominence of private lenders is what is going to complicate any attempt to resolve debt,” Chelwa stated. This is because bilateral debt has other, even political considerations. “It is more than financial returns. China has a willingness to suspend interest payments, to restructure debt, to defer it. But are the likes of BlackRock interested in that? What good does suspending debt payment do them?”

“Zambia is a test case, it is also an example of what is to come for much of the Global South as we deal, yet again, with another sovereign debt crisis.”

As entities such as BlackRock continue to reap obscene profits, the people of Zambia will bear the burden of an IMF bailout in which they had no say. In its statements, the Fund increasingly uses the term “homegrown” to refer to the arrangement’s policies. Chelwa has also denounced the co-optation of civil society organizations who lent credibility to the “opaque process that gave birth to such an anti-poor deal.”

“This is the IMF of the 21st century,” he said. “They have learned from their mistakes, not of policy, but of public relations… They call the programme homegrown, yet they impose structural benchmarks. If it was truly homegrown, why would we need an external party to impose milestones?”

https://peoplesdispatch.org/2022/09/22/ ... bal-south/

The red union will never fold!

Mbali Ngwenda of the Pan Africanism Today Secretariat writes about the struggles of United Textile Employees (UNITE), the radical textile workers’ union of Lesotho

September 23, 2022 by Mbali Ngwenda

(Photo: via Mbali Ngwenda)

The challenges that organized labor continues to face in the current world are becoming more intense, not just in Africa but all over the world. Organizations of the working class have a very difficult path to navigate: how do worker-leaders give confidence to their union membership in times of retrenchment bloodbaths? How do members of unions relate to the issues that seek to liquidate their unions and weaken their position as an immediate bulwark against capitalist exploitation?

Challenges to organized labor

Neoliberalism has had a direct, detrimental effect on the developments we see in labor movements today, and, globally, on the broader working class. In the past three or four years, workers have seen massive reversals in the gains that they had struggled for.

Retrenchments, the automation of the workplace, and clampdowns by the state on the rights to strike and to associate continue to negatively impact organized labor. The worker-led victories of the 1970s and 1990s—such as progressive labor laws and codes—are being aggressively attacked through the neoliberal order of today. The onslaughts of cost-cutting and austerity we have seen in recent years have exacerbated unemployment and directly resulted in decreasing membership in unions. The direct impact of these can be seen through the example of one union in the small, landlocked southern African country of Lesotho: UNITE (United Textile Employees).

The union makes us strong

UNITE has been growing quickly and has more than 10,000 members. In 2021, the union led a historic strike of textile and garment workers. As reported by Peoples Dispatch, this saw nearly 38,000 of roughly 40,000 workers in this sector—which accounts for 20% of the GDP of Lesotho—down tools for more than a month.

UNITE has become the largest union in the country’s textile industry, quickly approaching the threshold of 50% worker representation in all firms in which it organizes. Demonstrating the power of organized labor, as it did over the course of the 2021 strike, was an important victory.

Under attack

UNITE’s success at organizing workers has seen employers continue to, so far unsuccessfully, attempt to push UNITE out. Employers have turned to using their own “sweetheart unions” to advance this agenda, as in the case of the company Precious Garments.

Employers are justifying their attack on the union based on a free-market argument: UNITE is causing capital flight; therefore they cannot work with the union. They have gone as far as to write letters to the ministry of labor calling for the deregistration of the union.

At the height of this offensive against the Union, shop stewards were unilaterally dismissed from firms. The focal point of this attack was the dismissal of the union’s second vice president, Thathasela Mabatho. Here, employers used one of UNITE’s own members to collaborate against her to get her dismissed. In other cases, shop stewards and organizers have been denied entry into firms by employers while workers have been denied leave to attend political workshops during working hours. In some cases employers have gone as far as to deny workers representation by UNITE shop stewards.

The union had condemned these unfair labor practices and made an urgent application to the labor court in Lesotho. The court has since ruled in favor of the union. In its ruling, it said that UNITE could not be suspended in the workplace, and that Precious Garments and its general manager must pay the union’s outstanding dues. Put differently: the union must be recognized!

Precious Garments did not comply with the aforementioned order. The union filed for contempt of court against them and they won on September 13, 2022.

The judgment went on to state:

“That the respondents were outrightly contemptuous of [the] court’s clear and unambiguous interim orders that were served on them. Respondents seem to […] have refused and or failed for no justifiable causes whatsoever to comply with [the] court’s clear interim orders.”

“The applicant has all in all succeeded in establishing beyond reasonable doubt that the concerned respondents have been outrightly contemptuous of [the] court’s interim orders.”

The second respondent “Foley Chien is hereby committed to prison for a period of 90 days or until such time as he has purged his contempt as the general manager and representative of [Precious Garments]”.

“The victory means a lot to the organization. […] The right of the workers to be represented by their organization is restored.”

— Solong Senohe, General Secretary of United Textiles Employees

The union has also radically linked struggles in the workplace with struggles in the community. This is something that only the finest trade unionists of our era have done. The revival of activism remains an important element of building trade unions that supplement the economic struggles of workers and the political struggle for socialism.

UNITE stands as an example of what working-class formations are dealing with in these times of capitalist crisis and aggression. The union’s victory in court also reassures the labor movement that reversals of the hard won rights of workers will not be accepted haphazardly and without a fight.

UNITE continues to agitate for socialism at all times and remains at the center of a peoples’ transformation: never wavering from placing people before profits!

https://peoplesdispatch.org/2022/09/23/ ... ever-fold/