Diplomatic cables prove top U.S. Officials knew they were crossing Russia’s red lines on NATO expansion

Originally published: NewsClick.in on February 4, 2023 by Branko Marcetic (more by NewsClick.in) | (Posted Feb 06, 2023)

Nearly a year in, the war in Ukraine has cost hundreds of thousands of lives and brought the world to the brink of, in President Joe Biden’s own words, “Armageddon.” Alongside the literal battlefield, there has been a similarly bitter intellectual battle over the war’s causes.

Commentators have rushed to declare the long-criticised policy of NATO expansion as irrelevant to the war’s outbreak, or as a mere fig leaf used by Russian President Vladimir Putin to mask what former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and former Defence Secretary Robert Gates recently called “his messianic mission” to “reestablish the Russian Empire,” in a Washington Post opinion piece. Fiona Hill, a presidential adviser to two Republican administrations, has deemed these views merely the product of a “Russian information war and psychological operation,” resulting in “masses of the U.S. public… blaming NATO, or blaming the U.S. for this outcome.”

Yet a review of the public record and dozens of diplomatic cables made publicly available via WikiLeaks show that U.S. officials were aware, or were directly told over the span of years that expanding NATO was viewed by Russian officials well beyond Putin as a major threat and provocation; that expanding it to Ukraine was a particularly bright red line for Moscow; that such action would inflame and empower hawkish, nationalist parts of the Russian political spectrum; and that it could ultimately lead to war.

In a particularly prophetic set of warnings, U.S. officials were told that pushing for Ukrainian membership in NATO would not only increase the chance of Russian meddling in the country but also risked destabilising the divided nation—and that the United States and other NATO officials pressured Ukrainian leaders to reshape this unfriendly public opinion in response. All of this was told to U.S. officials in both public and private by not just senior Russian officials going all the way up to the presidency, but by NATO allies, various analysts and experts, liberal Russian voices critical of Putin, and even, sometimes, U.S. diplomats themselves.

This history is particularly relevant as U.S. officials now test the red line China has drawn around Taiwan’s independence, risking military escalation that will first and foremost be aimed at the island state. The U.S. diplomatic record regarding NATO expansion suggests the perils of ignoring or outright crossing another military power’s red lines and the wisdom of a more restrained foreign policy that treats other powers’ spheres of influence with the same care they extend to the United States.

An Early Exception

NATO expansion had been fraught from the start. The pro-Western, then-Russian President Boris Yeltsin had told then-US President Bill Clinton he “[saw] nothing but humiliation for Russia if you proceed” with plans to renege on the verbal promises made years earlier not to extend NATO eastward, and warned that this move would be “sowing the seeds of mistrust” and would “be interpreted, and not only in Russia, as the beginning of a new split in Europe.” Just as containment architect George Kennan had predicted, the decision to go ahead with NATO expansion helped inflame Russian hostility and nationalism: The Duma (the Russian parliament) declared it “the largest military threat to our country over the last 50 years,” while the leader of the opposition Communist Party called it “a Treaty of Versailles for Russia.”

By the time Putin became president the day before the new millennium, “the initial hopes and plans of the early ’90s [were] dead,” a leading liberal Russian politician declared. The first round of NATO enlargement was followed by the organisation bombing Yugoslavia in 1999, which was done without the UN Security Council authorization, and triggered Russia to cut off contact with the alliance. By 2000, the revised Russian national security strategy warned that NATO’s use of force beyond its borders would be seen as “a threat of destabilization of the whole strategic situation,” while military officers and politicians started claiming “that if NATO expands further, it would ‘create a base to intervene in Russia itself,’” the Washington Post reported.

Ironically, there would be one exception to the next two decades’ worth of rising tensions over NATO’s eastward expansion that followed: the early years of Putin’s presidency, when the new Russian president defied the Russian establishment to try and make outreach to the United States. Under Putin, Moscow re-established relations with NATO, finally ratified the START II arms control treaty, and even publicly floated the idea of Russia eventually joining the alliance, inviting attacks from his political rivals for doing so. Even so, Putin continued to raise Moscow’s traditional concerns about the alliance’s expansion, telling NATO’s secretary-general it was “a threat to Russia” in February 2001.

“[If] a country like Russia feels threatened, this would destabilize the situation in Europe and the entire world,” he said in a speech in Berlin in 2000.

Putin softened his opposition as he sought to make common cause with then-President George W. Bush administration. “If NATO takes on a different shape and is becoming a political organization, of course, we would reconsider our position with regard to such expansion, if we are to feel involved in the processes,” he said in October 2001, drawing attacks from political rivals and other Russian elites.

As NATO for the first time granted Russia a consultative role in its decision-making in 2002, Putin sought to assist its expansion. Then-Italian President Silvio Berlusconi made a “personal request” to Bush, according to an April 2002 cable, to “understand Putin’s domestic requirements,” that he “needs to be seen as part of the NATO family,” and to give him “help in building Russian public opinion to support NATO enlargement.” In another cable, a top-ranking U.S. State Department official urged holding a NATO-Russia summit to “help President Putin neutralise opposition to enlargement,” after the Russian leader said allowing NATO expansion without an agreement on a new NATO-Russia partnership would be politically impossible for him.

This would be the last time any Russian openness toward NATO expansion was recorded in the diplomatic record published by WikiLeaks.

Allies Weigh In

By the middle of the 2000s, U.S.-Russian relations had deteriorated, partly owing to Putin’s bristling at U.S. criticism of his growing authoritarianism at home, and to U.S. opposition to his meddling in the 2004 Ukrainian election. But as explained in a September 2007 cable by then-President of New Eurasia Foundation Andrey Kortunov, now director general of the Russian International Affairs Council—who has publicly criticized both Kremlin policy and the current war—United States mistakes were also to blame, including Bush’s invasion of Iraq and a general sense that he had given little in return for Putin’s concessions.

“Putin had clearly embarked on an ‘integrationist’ foreign policy at the beginning of his second presidential term, which was fueled by the 9/11 terrorist attacks and good relations with key leaders like President Bush” and other leading NATO allies, Kortunov said according to the cable. “However,” he said, “a string of perceived anti-Russian initiatives,” which included Bush’s withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty and “further expansion of NATO,” ultimately “dashed Putin’s hopes.”

What followed was a steady drumbeat of warnings about NATO’s expansion, particularly regarding neighboring Ukraine and Georgia, much of it from Washington’s NATO allies.

“[Former French presidential diplomatic adviser Maurice] Gourdault-Montagne warned that the question of Ukrainian accession to NATO remained extremely sensitive for Moscow, and concluded that if there remained one potential cause for war in Europe, it was Ukraine,” reads a September 2005 cable.

He added that some in the Russian administration felt we were doing too much in their core zone of interest, and one could wonder whether the Russians might launch a move similar to Prague in 1968, to see what the West would do.

This was just one of many similar warnings from French officials that admitting Ukraine and Georgia into NATO “would cross Russian ‘tripwires’,” for instance. A February 2007 cable records then-French Director General for Political Affairs Gérard Araud’s recounting of “a half-hour anti-US harangue” by Putin in which he “linked all the dots” of Russian unhappiness with U.S. behaviour, including “US unilateralism, its denial of the reality of multipolarity, [and] the anti-Russian nature of NATO enlargement.”

Germany likewise raised repeated concerns about a potentially bad Russian reaction to a NATO Membership Action Plan (MAP) for Ukraine and Georgia, with then-Deputy National Security Adviser Rolf Nikel stressing that Ukraine’s entry was particularly sensitive. “While Georgia was ‘just a bug on the skin of the bear,’ Ukraine was inseparably identified with Russia, going back to Vladimir of [Kyiv] in 988,” Nikel recounted, according to the cable.

Other NATO allies repeated similar concerns. In a January 2008 cable, Italy affirmed it was a “strong advocate” for other states’ entry into the alliance, “but is concerned about provoking Russia through hurried Georgian integration.” Norway’s then-Foreign Minister (who is now the prime minister) Jonas Gahr Støre made a similar point in an April 2008 cable, even as he insisted Russia mustn’t be able to veto NATO’s decisions. “At the same time he says that he understands Russia’s objections to NATO enlargement and that the alliance needs to work to normalize the relationship with Russia,” reads the cable.

Almost Complete Consensus

The thinkers and analysts that U.S. officials conferred with likewise made clear that the anxieties of Russian elites over NATO and its expansion, and the lengths they might go to counteract it. Many were transmitted by then-US Ambassador to Russia William Burns, who is presently Biden’s CIA director.

Recounting his conversations with various “Russian observers” from both regional and U.S. think tanks, Burns concluded in a March 2007 cable that “NATO enlargement and U.S. missile defense deployments in Europe play to the classic Russian fear of encirclement.” Ukraine and Georgia’s entry “represents an ‘unthinkable’ predicament for Russia,” he reported six months later, warning that Moscow would “cause enough trouble in Georgia” and counted on “continued political disarray in Ukraine” to halt it. In an especially prescient set of cables, he summed up scholars’ views that the emerging Russia-China relationship was largely “the by-product of ‘bad’ U.S. policies,” and was unsustainable—“unless continued NATO enlargement pushed Russia and China even closer together.”

Cables record Russian intellectuals across the political spectrum making such points again and again. One June 2007 cable records the words of a “liberal defense expert Aleksey Arbatov” and the “liberal editor” of a leading Russian foreign policy journal, Fyodor Lukyanov, that after Russia had done “everything to ‘help’ the U.S. post-9/11, including opening up Central Asia for coalition anti-terrorism efforts,” it had expected “respect for Russia’s ‘legitimate interests.’” Instead, Lukyanov said, it had been “confronted with NATO expansion, zero-sum competition in Georgia and Ukraine, and U.S. military installations in Russia’s backyard.”

“Ukraine was, in the long term, the most potentially destabilizing factor in U.S.-Russian relations, given the level of emotion and neuralgia triggered by its quest for NATO membership,” stated the counsel of Dmitri Trenin, then-deputy director of the Russian branch of the U.S.-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in a Burns-authored February 2008 cable. For Ukraine, he said prophetically, it would mean “that elements within the Russian establishment would be encouraged to meddle, stimulating U.S. overt encouragement of opposing political forces, and leaving the United States and Russia in a classic confrontational posture.”

Indeed, opposing NATO’s enlargement eastward, particularly in Ukraine and Georgia, was “one of the few security areas where there is almost complete consensus among Russian policymakers, experts and the informed population,” stated a cable of March 2008, citing defense and security experts. Ukraine was the “line of last resort” that would complete Russia’s encirclement, said one defense expert, and its entry into NATO was universally viewed by the Russian political elite as an “unfriendly act.” Other experts cautioned “that Putin would be forced to respond to Russian nationalist feelings opposing membership” of Georgia, and that offering MAP to either Ukraine or Georgia would trigger a cut-back in the Russian military’s genuine desire for cooperation with NATO.

From Liberals to Hardliners

These analysts were reiterating what cables show U.S. officials heard again and again from Russian officials themselves, whether diplomats, members of parliament, or senior Russian officials all the way up to the presidency, recorded in nearly three-dozen cables at least.

NATO enlargement was “worrisome,” said one Duma member, while Russian generals were “suspicious of NATO and U.S. intentions,” cables record. Just as analysts and NATO officials had said, Kremlin officials characterized NATO’s designs on Georgia and Ukraine as especially objectionable, with the Russian Ambassador to NATO from 2008 to 2011, Dmitry Rogozin, stressing in a February 2008 cable that offering MAP to either “would negatively impact NATO’s relations with Russia” and “raise tension along the borders between NATO and Russia.”

Then-Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Grigory Karasin “underscored the depth of Russian opposition” to their membership, a different March 2008 cable stated, underlining that the “political elite firmly believes” “that the accession of Ukraine and Georgia represented a direct security threat to Russia.” The future, Karasin said, rested on the “strategic choice” Washington made about “‘what kind of Russia’” it wanted to deal with—‘a Russia that is stable and ready to calmly discuss issues with the U.S., Europe and China, or one that is deeply concerned and filled with nervousness.’”

Indeed, numerous officials—including then-Director for Security and Disarmament Anatoly Antonov, who is currently serving as Russia’s ambassador to the United States—warned pushing ahead would produce a less cooperative Russia. Pushing NATO’s borders to the two former Soviet states “threatened Russian and the entire region’s security, and could also negatively impact Russia’s willingness to cooperate in the [NATO-Russia Council],” one Russian foreign ministry official warned, while others pointed to the policy to explain Putin’s threats to suspend the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) treaty. “CFE would not survive NATO enlargement,” went a Russian threat in one March 2008 cable.

Maybe most pertinent were the words of Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, at the time a veteran diplomat respected in the West, and who continues to serve in the position today. At least eight cables—many, though not all of them, written by Burns— r ecord Lavrov’s expressions of opposition to expanding NATO to Ukraine and Georgia over the course of 2007-2008, when Bush’s decision, over the objections of allies, to publicly affirm their future accession led to a spike in tensions.

“While Russia might believe statements from the West that NATO was not directed against Russia, when one looked at recent military activities in NATO countries… they had to be evaluated not by stated intentions but by potential,” went Burns’s summary of Lavrov’s annual foreign policy review in January 2008. On the same day, he wrote, a foreign ministry spokesperson warned that Ukraine’s “likely integration into NATO would seriously complicate the many-sided Russian-Ukrainian relations” and lead Moscow to “have to take appropriate measures.”

Besides being an easy way to garner domestic support from nationalists, Burns wrote, “Russia’s opposition to NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia is both emotional and based on perceived strategic concerns about the impact on Russia’s interests in the region.”

“While Russian opposition to the first round of NATO enlargement in the mid-1990s was strong, Russia now feels itself able to respond more forcefully to what it perceives as actions contrary to its national interests,” he concluded.

Lavrov’s criticism was shared by a host of other officials, not all of them hardliners. Burns recounted a meeting with former Prime Minister Yevgeny Primakov, a Gorbachev protégé who had negotiated over NATO’s first expansion with former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who warmly eulogised him years later as a pragmatist. The U.S. push for MAP for Georgia and Ukraine “‘infuriated’ Russians and threatened other areas of U.S.-Russia strategic cooperation,” Primakov had said, according to Burns, mentioning Primakov was asked later that day on TV about rethinking Crimea’s status as Ukrainian territory. “[T]his is the kind of discussion that MAP produces,” he said—meaning that it inflamed nationalist and hardline sentiment.

“Primakov said that Russia would never return to the era of the early 1990s and it would be a ‘colossal mistake’ to think that Russian reactions today would mirror those during its time of strategic weakness,” Burns’s cable stated.

This went all the way to the top, as U.S. officials noted in cables reacting to a famously strident speech Putin gave at the Munich Security Conference in February 2007, which saw Putin assail NATO expansion and other policies as part of a wider, destabilising U.S. abuse of its sole-superpower status. Putin’s tone may have been “unusually sharp,” Primakov told Burns, but its substance “reflected well-known Russian complaints predating Putin’s election,” shown by the fact that “talking heads and Duma members were almost unanimous” in supporting the speech. A year later, a March 2008 cable reported then-German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s farewell, two-hour-long meeting with Putin, in which he “argued strongly” against MAP for Ukraine and Georgia.

Putin’s Exit

Any illusions this stance would evaporate with Putin leaving the presidency were quickly dispelled. Such warnings continued and, if anything, grew more intense after Putin was replaced by his liberal successor, Dmitry Medvedev as president of Russia, whose ascent sparked hopes for a more democratic Russia and an improved U.S.-Russian relationship.

Under Medvedev, officials from the Russian ambassador to NATO and various officials in the foreign ministry to the chairman of the Duma’s international affairs committee made much the same warnings, cables show. In some cases, as with Karasin and Lavrov, it was the same officials making these long-standing complaints.

Medvedev himself “reiterated well known Russian positions on NATO enlargement” to Merkel on his first trip to Europe in June 2008, even as he avoided bringing up MAP for Ukraine and Georgia specifically. “Behind Medvedev’s polite demeanor, Russian opposition to NATO enlargement remained a red-line, according to both conservative and moderate observers,” one June 2008 cable reads, a view shared by a leading liberal analyst. Even critics to his right read Medvedev’s words as “an implicit commitment to use Russian economic, political and social levers to raise the costs for Ukraine and Georgia” if they moved closer to the alliance. The cable’s author, then-Deputy Chief of Mission at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow Daniel Russell, concluded he “agree[d] with the common wisdom.”

By August 2008, following the war with Georgia, Medvedev started to sound a lot more like his predecessor, threatening to cut ties with the alliance and restating grievances about encirclement. A cable from after the end of the five-day war between Russia and Georgia—which an EU-commissioned report would later blame the Georgian government for starting—stated that “even the most pro-Western political experts” were “pointing the finger at the U.S.” for jeopardizing the U.S.-Russian relations, with U.S.’s dismissal of Russia’s concerns over, among other things, NATO expansion being a key part of their analysis. Echoing Burns, one analyst argued that Russia finally felt “strong enough to stand up to the West” when it ignored its concerns.

Those concerns were central at a roundtable of Russian analysts months later— a January 2009 cable showed—who explained to a group of visiting U.S. congresspeople Russians’ “deep displeasure” with the U.S. government, and stressed the “bitter divorce” between Russia and Georgia would be even uglier with Ukraine. Pushing MAP for the country “helped the ‘America haters come to power’ in Russia and gave legitimacy to the hard-liners’ vision of ‘fortress Russia,’” said one Russian analyst.

Increasingly, cables show, such warnings came from liberals, even those who hadn’t previously viewed NATO and the United States as Russia’s chief threats. An August 2008 cable described a meeting with Russian Human Rights Ombudsman Ambassador Vladimir Lukin—described as “a liberal on the Russian political scene, someone disposed toward cooperation with the US”—who explained Medvedev’s post-war recognition of the independence of Georgia’s breakaway regions, which he had at first opposed, as a security-driven response to NATO’s drift toward Russia’s borders. Because escalations like the 2008 U.S.-Poland missile defence agreement showed anti-Russia actions “would not stop,” he said, “Moscow had to show that, like the U.S., it can and will take steps it deems necessary to defend its interests.”

The cable concluded that Lukin’s views “reflect the thinking of the majority of Russian foreign policy elite.”

Selling NATO to Ukraine

Other than Burns—whose Bush-era memos warning of the breadth of Russian opposition to NATO expansion and that it would provoke intensified meddling in Ukraine have become famous since the Russian invasion—US officials largely reacted with dismissal.

Russian objections to the policy and other long-simmering issues were described over and over in the cables as “oft-heard,” “old,” “nothing new,” and “largely predictable,” a “familiar litany” and a “rehashing” that “provided little new substance.” Even NATO’s ally Norway’s position that it understood Russian objections even as it refused to let Moscow veto the alliance’s moves was labeled a case of “parroting Russia’s line.”

U.S. officials were similarly dismissive of explicit warnings—from Kremlin officials, NATO allies, experts and analysts, even Ukrainian leadership—that Ukraine was “internally divided over NATO membership” and that public support for the move was “not fully ripe.” The east-west split within Ukraine over the idea of NATO membership made it “risky,” German officials cautioned, and could “break up the country.” Ukraine’s three leading politicians all “took foreign policy positions based on domestic political considerations, with little regard to the long-term effects on the country,” one said.

Those very politicians likewise made clear public opinion wasn’t there, whether anti-Russian former Foreign Minister Volodymyr Ogryzko of Ukraine, or more Russian-friendly former Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych—later misleadingly painted as a Kremlin puppet and was ousted as president in the 2014 Maidan protests—who boasted to a U.S. diplomat that support for NATO had jumped under his tenure. In response, the cables show, NATO officials pressed Ukrainian leaders to take a firm public stance in favor of joining, and discussed how to persuade Ukraine’s population “so that they would be more favorable [toward] it.” Ogryzko later disclosed to Merkel “that a public education campaign is already underway,” and that Ukraine “had discussed the issue of public education campaigns with Slovakia and other nations that had joined NATO recently.”

This came in spite of acknowledged risks. Cables record liberal Russian analysts cautioning “that [then-Ukrainian President Viktor] Yushchenko was using NATO membership to shore up a Ukrainian national identity that required casting Russia in the role of enemy,” and that “because membership remained divisive in Ukrainian domestic politics, it created an opening for Russian intervention.”

“Experts tell us that Russia is particularly worried that the strong divisions in Ukraine over NATO membership, with much of the ethnic-Russian community against membership, could lead to a major split, involving violence or at worst, civil war,” Burns wrote in February 2008. Russia, he further wrote, would then “have to decide whether to intervene; a decision Russia does not want to have to face.”

Despite the dismissive attitude of many U.S. officials, parts of the U.S. national security establishment clearly understood Russian objections weren’t mere “muscle-flexing.” The Kremlin’s anxieties over a “direct military attack on Russia” were “very real,” and could drive its leaders to make rash, self-defeating decisions, stated a 2019 report from the Pentagon-funded RAND Corporation that explored theoretical strategies for overextending Russia.

“Providing more U.S. military equipment and advice” to Ukraine, it stated, could lead Moscow to “respond by mounting a new offensive and seizing more Ukrainian territory”—something not necessarily good for U.S. interests, let alone Ukraine’s, it noted.

Warnings Ignored

Nevertheless, in the years, months, and weeks that led up to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, successive U.S. administrations continued on the same course.

Ukraine’s cooperation with NATO has “deepened over time,” the alliance itself says today. By the war’s outbreak, the country frequently hosted Western troops at a military base, Ukrainian soldiers received NATO training, it planned two new NATO-linked naval bases, and has received unprecedented sums of U.S. military aid, including offensive arms—a former President Donald Trump policy his liberal predecessor had explicitly rejected, out of concern for provoking a disastrous response from Moscow. Three months before the invasion, Ukraine and the United States signed an updated Charter on Strategic Partnership “guided” by Bush’s controversial Bucharest declaration, which both deepened security cooperation between the two countries and supported Ukraine’s membership aspirations, viewed as an escalation in Moscow.

As U.S. military activity has increased in the region since 2016, sometimes involving Ukraine and Georgia, NATO-Russian tensions have ratcheted up too. While Moscow publicly objected to U.S. missions in Europe that experts feared were too provocative, NATO and Russian forces have experienced thousands of dangerous military encounters in the region and elsewhere. By December 2022, with fears of invasion ramping up, Putin told Biden personally that “the eastward expansion of the Western alliance was a major factor in his decision to send troops to Ukraine’s border,” the Washington Post reported.

None of this means other factors played no role in the war’s outbreak, from Russian domestic pressures and Putin’s own dim view of Ukrainian independence to the copious other well-known Russian grievances toward U.S. policy that frequently appear in the diplomatic record, too. Nor does it mean, as hawks argue, that this somehow “justifies” Putin’s war, any more than understanding how U.S. foreign policy has fuelled anti-American terrorism that “justifies” those crimes.

What it does mean is that claims that Russian unhappiness over NATO expansion is irrelevant, a mere “fig leaf” for pure expansionism, or simply Kremlin propaganda are belied by this lengthy historical record. Rather, successive U.S. administrations pushed ahead with the policy despite being warned copiously for years—including by the analysts who advised them, by allies, even by their own officials—that it would feed Russian nationalism, create a more hostile Moscow, foster instability and even civil war in Ukraine, and could eventually lead to Russian military intervention, all of which ended up happening.

“I don’t accept anyone’s red line,” Biden said in the lead-up to the invasion, as his administration rejected negotiations with Moscow over Ukraine’s NATO status. We can only imagine the world in which he and his predecessors had.

https://mronline.org/2023/02/06/diploma ... expansion/

***********

Airmen with the 3rd Munitions Squadron assemble a rack of inert small diameter bombs during readiness training at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska, Feb. 9, 2018. The small diameter bomb is a precise and accurate weapon that allows the the F-22 Raptor to deliver decisive air power. (U.S. Air Force photo by Alejandro Peña)

U.S. sends long-range missiles to Ukraine

Originally published: World Socialist Web Site (WSWS) on February 4, 2023 by Andre Damon (more by World Socialist Web Site (WSWS)) | (Posted Feb 06, 2023)

The White House announced Friday that it would send long-range missiles capable of striking nearly 100 miles into Russian territory to Ukraine, in one of the most significant escalations of U.S. involvement in the war with Russia to date.

Following Washington’s tradition of the “Friday afternoon news dump,” the announcement was timed so as to garner as little public attention as possible.

The pliant American media supported the Biden administration’s goal of keeping the American public from understanding the consequences of this action. This massive escalation of the war against Russia received effectively no media coverage. It was not featured on the front pages of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, or Washington Post, and was not reported on the evening network news shows.

The weapons system, known as the ground-launched Small Diameter Bomb, is a rocket-launched maneuverable glide bomb with double the range of the HIMARS missiles Washington has already provided.

The announcement marks a repudiation of Biden’s pledge in May that “We are not encouraging or enabling Ukraine to strike beyond its borders,” and his declaration that “we’re not going to send to Ukraine rocket systems that strike into Russia.”

The announcement is the latest in a whirlwind escalation of U.S. involvement in the war over the past week. On January 26, the White House declared that it would send 31 Abrams main battle tanks to Ukraine, as part of a coalition of NATO countries sending over 120 main battle tanks in the first “wave.”

No sooner was this announcement made than the White House revealed that it was in discussions to send F-16 fighters to Ukraine, against the backdrop of demands by Democratic and Republican politicians and dominant sections of the U.S. media to send the aircraft.

The expected announcement of the new long-range weapons comes as press reports indicate that the Biden administration is discussing openly endorsing a Ukrainian assault on the predominantly Russian-speaking peninsula of Crimea, which Russia has claimed as its territory since 2014.

While the Biden administration endorsed the Zelensky government’s Crimean Platform back in 2021, which entails the “retaking of Crimea,” since the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, Washington had toned down its explicit endorsement for the official war aim of the Zelensky government in order to hide the massively escalatory character of its involvement in the war.

Now, however, the New York Times reports, “(T)he Biden administration is finally starting to concede that Kyiv may need the power to strike the Russian sanctuary, even if such a move increases the risk of escalation.”

The Times writes that “the Biden administration is considering what would be one of its boldest moves yet, helping Ukraine to attack the peninsula.”

In an article for the think tank magazine Foreign Affairs, entitled “What Ukraine Needs to Liberate Crimea,” United States Army Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Vindman declared, “Washington should give Ukraine the weapons and assistance it needs to win quickly and decisively.” Vindman is the former director for European affairs for the U.S. National Security Council.

In the article, Vindman explained how a NATO-backed Ukrainian offensive against Crimea would proceed:

The first step would be to pin down Russia’s forces in the Kherson and Luhansk regions and in the northern part of Donetsk. Next, Ukraine would free the remainder of Zaporizhzhia Province and push through southern Donetsk to reach the Sea of Azov, severing Russia’s land bridge to Ukraine. Ukrainian forces would also need to destroy the Kerch Strait Bridge, which connects Russia to the Crimean Peninsula and allows Moscow to resupply its troops by road and rail.

What none of the planners of this offensive admit, however, is that its implementation will require a massive expansion of NATO involvement in the war, including not only the deployment of advanced weapons systems, but the direct deployment of NATO troops.

Last week, explaining the deployment of the M1 Abrams tanks to Ukraine, the WSWS outlined how such a scenario could unfold:

The significance of Biden’s announcement lies less in the battlefield impact of the tanks than in the consequences of deploying them. The turbine-driven Abrams tanks will require a massive logistical network inside Ukraine, involving large numbers of specialist American contractors. Attacks on these supply networks and American personnel servicing the tanks will then be used to press for implementation of a “no-fly zone” and the deployment of U.S. and NATO troops to Ukraine.

Just one week after these words were written, the initial stages of this scenario are already being put into place.

On Friday, Politico reported that “A group of former military officers and private donors is raising money to send Western mechanics close to the Ukrainian frontlines, where they will repair battle-damaged donated weapons and vehicles that have been flooding into the country.”

The report continued, “The plan is to find 100 to 200 experienced contractors who would travel to Ukraine and embed themselves with small units near the front lines. Under the project, called Trident Support, those contractors would in turn teach the Ukrainian troops how to fix their equipment on the fly.”

The claim that this initiative is being led by “retired” officers is merely a fraudulent pretense distancing the Biden administration from this deployment. While the deployment of the contractors may be “voluntary,” threats to the safety of the hundreds of American personnel on the front lines maintaining American vehicles could serve just as well as a pretext for U.S. escalation of the war.

https://mronline.org/2023/02/06/u-s-sen ... o-ukraine/

**********

More Evidence That The West Sabotaged Peace In Ukraine

Days after the war in Ukraine began it was reported by The New York Times that “President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine has asked the Israeli prime minister, Naftali Bennett, to mediate negotiations in Jerusalem between Ukraine and Russia.” In a recent interview, Bennett made some very interesting comments about what happened during those negotiations in the early days of the war.

In a new article titled “Former Israeli PM Bennett Says US ‘Blocked’ His Attempts at a Russia-Ukraine Peace Deal,” Antiwar’s Dave DeCamp writes the following:

Former Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett said in an interview posted to his YouTube channel on Saturday that the US and its Western allies “blocked” his efforts of mediating between Russia and Ukraine to bring an end to the war in its early days.

On March 4, 2022, Bennett traveled to Russia to meet with President Vladimir Putin. In the interview, he detailed his mediation at the time between Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, which he said he coordinated with the US, France, Germany, and the UK.

Bennett said that both sides agreed to major concessions during his mediation effort.

…

But ultimately, the Western leaders opposed Bennet’s efforts. “I’ll say this in the broad sense. I think there was a legitimate decision by the West to keep striking Putin and not [negotiate],” Bennett said.

When asked if the Western powers “blocked” the mediation efforts, Bennet said, “Basically, yes. They blocked it, and I thought they were wrong.”

Bennett says the concessions each side was prepared to make included the renunciation of future NATO membership for Ukraine, and on Russia’s end dropping the goals of “denazification” and Ukrainian disarmament. As DeCamp notes, this matches up with an Axios report from early March that “According to Israeli officials, Putin’s proposal is difficult for Zelensky to accept but not as extreme as they anticipated. They said the proposal doesn’t include regime change in Kyiv and allows Ukraine to keep its sovereignty.”

Bennett is about as unsavory a character as exists in the world today, but Israel’s complicated relationship with this war lends itself to the occasional release of information not fully in alignment with the official imperial line. And his comments here only add to a pile of information that’s been coming out for months which says the same thing, not just regarding the sabotage of peace talks in March but in April as well.

In May of last year Ukrainian media reported that then-British prime minister Boris Johnson had flown to Kyiv the previous month to pass on the message on behalf of the western empire that “Putin is a war criminal, he should be pressured, not negotiated with,” and that “even if Ukraine is ready to sign some agreements on guarantees with Putin, they are not.”

In April of last year, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said that “there are those within the NATO member states that want the war to continue, let the war continue and Russia gets weaker.” Shortly thereafter, US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin said that the goal in Ukraine is “to see Russia weakened.”

A September Foreign Affairs report by Fiona Hill asserts that in April of last year a peace deal had been in the works between Moscow and Kyiv, which would presumably have been the agreement that Johnson et al were able to sabotage:

According to multiple former senior U.S. officials we spoke with, in April 2022, Russian and Ukrainian negotiators appeared to have tentatively agreed on the outlines of a negotiated interim settlement: Russia would withdraw to its position on February 23, when it controlled part of the Donbas region and all of Crimea, and in exchange, Ukraine would promise not to seek NATO membership and instead receive security guarantees from a number of countries.

In March of last year Bloomberg’s Niall Ferguson reported that sources in the US and UK governments had told him the real goal of western powers in this conflict is not to negotiate peace or end the war quickly, but to prolong it in order “bleed Putin” and achieve regime change in Moscow. Ferguson wrote that he has reached the conclusion that “the U.S. intends to keep this war going,” and says he has other sources to corroborate this:

“The only end game now,” a senior administration official was heard to say at a private event earlier this month, “is the end of Putin regime. Until then, all the time Putin stays, [Russia] will be a pariah state that will never be welcomed back into the community of nations. China has made a huge error in thinking Putin will get away with it. Seeing Russia get cut off will not look like a good vector and they’ll have to re-evaluate the Sino-Russia axis. All this is to say that democracy and the West may well look back on this as a pivotal strengthening moment.”

I gather that senior British figures are talking in similar terms. There is a belief that “the U.K.’s No. 1 option is for the conflict to be extended and thereby bleed Putin.” Again and again, I hear such language. It helps explain, among other things, the lack of any diplomatic effort by the U.S. to secure a cease-fire. It also explains the readiness of President Joe Biden to call Putin a war criminal.

All this taken together heavily substantiates the claim made by Vladimir Putin this past September that Russia and Ukraine had been on the cusp of peace shortly after the start of the war, but western powers ordered Kyiv to “wreck” the negotitations.

“After the start of the special military operation, in particular after the Istanbul talks, Kyiv representatives voiced quite a positive response to our proposals,” Putin said. “These proposals concerned above all ensuring Russia’s security and interests. But a peaceful settlement obviously did not suit the West, which is why, after certain compromises were coordinated, Kyiv was actually ordered to wreck all these agreements.”

Month after month it’s been reported that US diplomats have been steadfastly refusing to engage in diplomacy with Russia to help bring an end to this war, an inexcusable rejection that would only make sense if the US wants this war to continue. And comments from US officials continually make it clear that this is the case.

In March of last year President Biden himself acknowledged what the real game is here with an open call for regime change, saying of Putin, “For God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power.” Statements from the Biden administration in fact indicate that they expect this war to drag on for a long time, making it abundantly clear that a swift end to minimize the death and destruction is not just uninteresting but undesirable for the US empire.

US officials are becoming more and more open about the fact that they see this war as something that serves their strategic objectives, which would of course contradict the official narrative that the western empire did not want this war and the infantile fiction that Russia’s invasion was “unprovoked”. Recent examples of this would include Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s speech ahead of Zelensky’s visit to Washington in December.

“President Zelensky is an inspiring leader,” McConnell said in his speech ahead of the Ukrainian president’s visit to Washington. “But the most basic reasons for continuing to help Ukraine degrade and defeat the Russian invaders are cold, hard, practical American interests. Helping equip our friends in Eastern Europe to win this war is also a direct investment in reducing Vladimir Putin’s future capabilities to menace America, threaten our allies, and contest our core interests.”

In May of last year Congressman Dan Crenshaw said on Twitter that “investing in the destruction of our adversary’s military, without losing a single American troop, strikes me as a good idea.”

Indeed, a report by the empire-funded Center for European Policy Analysis titled “It’s Costing Peanuts for the US to Defeat Russia” asserts that the “US spending of 5.6% of its defense budget to destroy nearly half of Russia’s conventional military capability seems like an absolutely incredible investment.”

In May of last year US Senator Joe Manchin said at the World Economic Forum that he opposes any kind of peace agreement between Ukraine and Russia, preferring instead to use the conflict to hurt Russian interests and hopefully remove Putin.

“I am totally committed, as one person, to seeing Ukraine to the end with a win, not basically with some kind of a treaty; I don’t think that is where we are and where we should be,” Manchin said.

“I mean basically moving Putin back to Russia and hopefully getting rid of Putin,” Manchin added when asked what he meant by a win for Ukraine.

“I believe strongly that I have never seen, and the people I talk strategically have never seen, an opportunity more than this, to do what needs to be done,” Manchin later added.

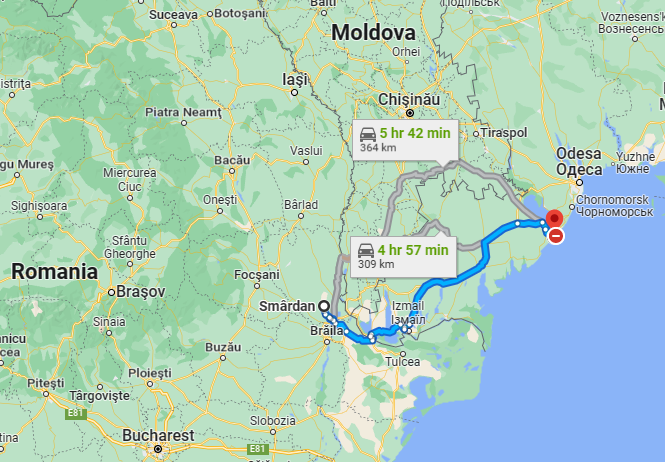

Then you’ve got US officials telling the press that they plan to use this war to hurt Russia’s fossil fuel interests, “with the long-term goal of destroying the country’s central role in the global energy economy” according to The New York Times. You’ve also got the fact that the US State Department can’t stop talking about how great it is that Russia’s Nord Stream Pipelines were sabotaged in September of last year, with Secretary of State Antony Blinken saying the Nord Stream bombing “offers tremendous strategic opportunity” and Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Victoria Nuland saying the Biden administration is “very gratified to know that Nord Stream 2 is now, as you like to say, a hunk of metal at the bottom of the sea.”

The US empire is getting everything it wants out of this proxy war. That’s why it knowingly provoked this war, that’s why it repeatedly sabotaged the outbreak of peace after the war broke out, and that’s why this proxy war has no exit strategy. The empire is getting everything it wants from this war, so why wouldn’t it do everything in its power to obstruct peace?

I mean, besides the obvious unforgivable depravity of it all, of course. The empire has always been fine with cracking a few hundred thousand human eggs in order to cook the imperial omelette. It is unfathomably, unforgivably evil, though, and it should outrage everyone.

https://caitlinjohnstone.com/2023/02/06 ... n-ukraine/

*************

From Cassad's Telegram account:

Colonelcassad

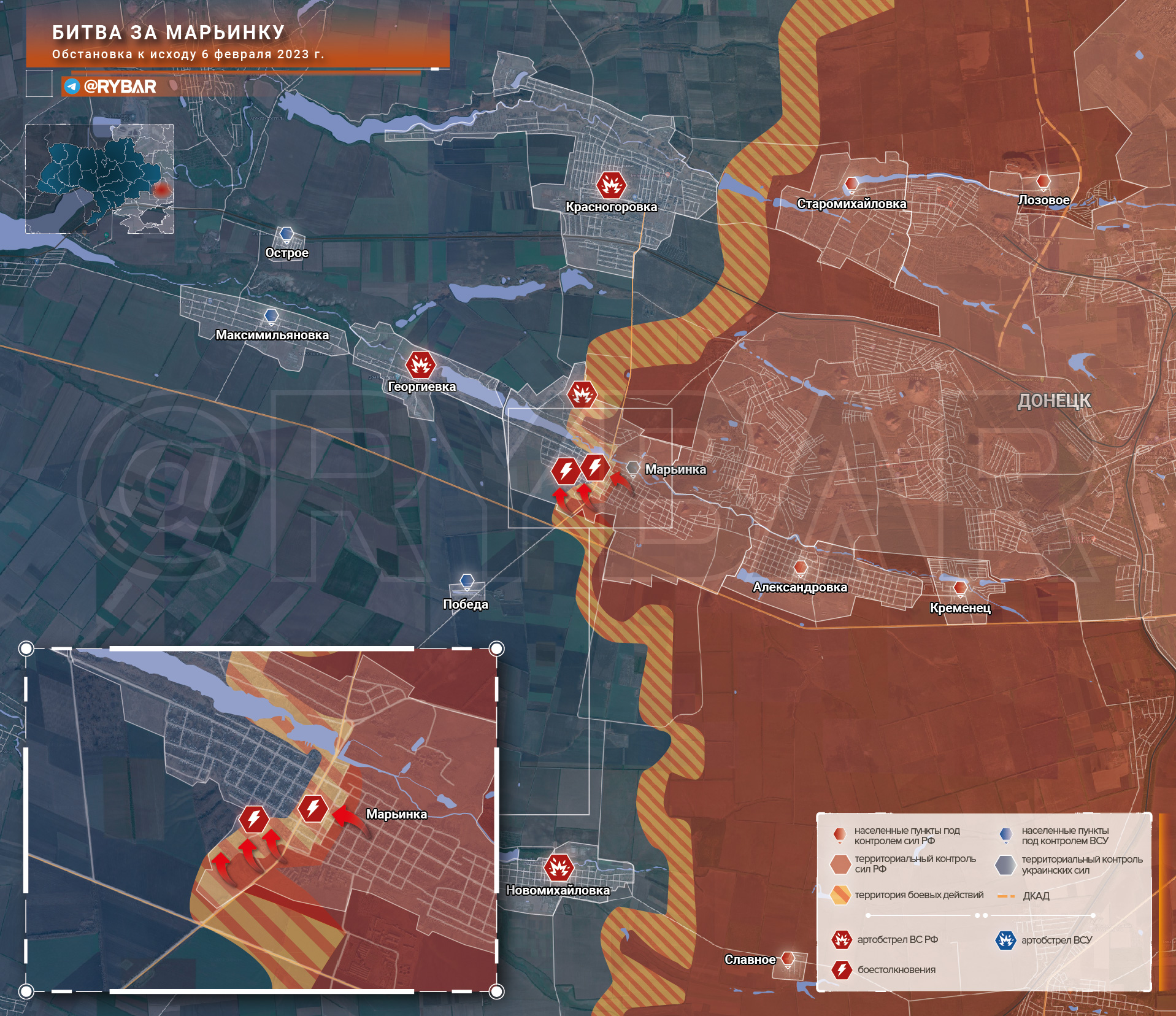

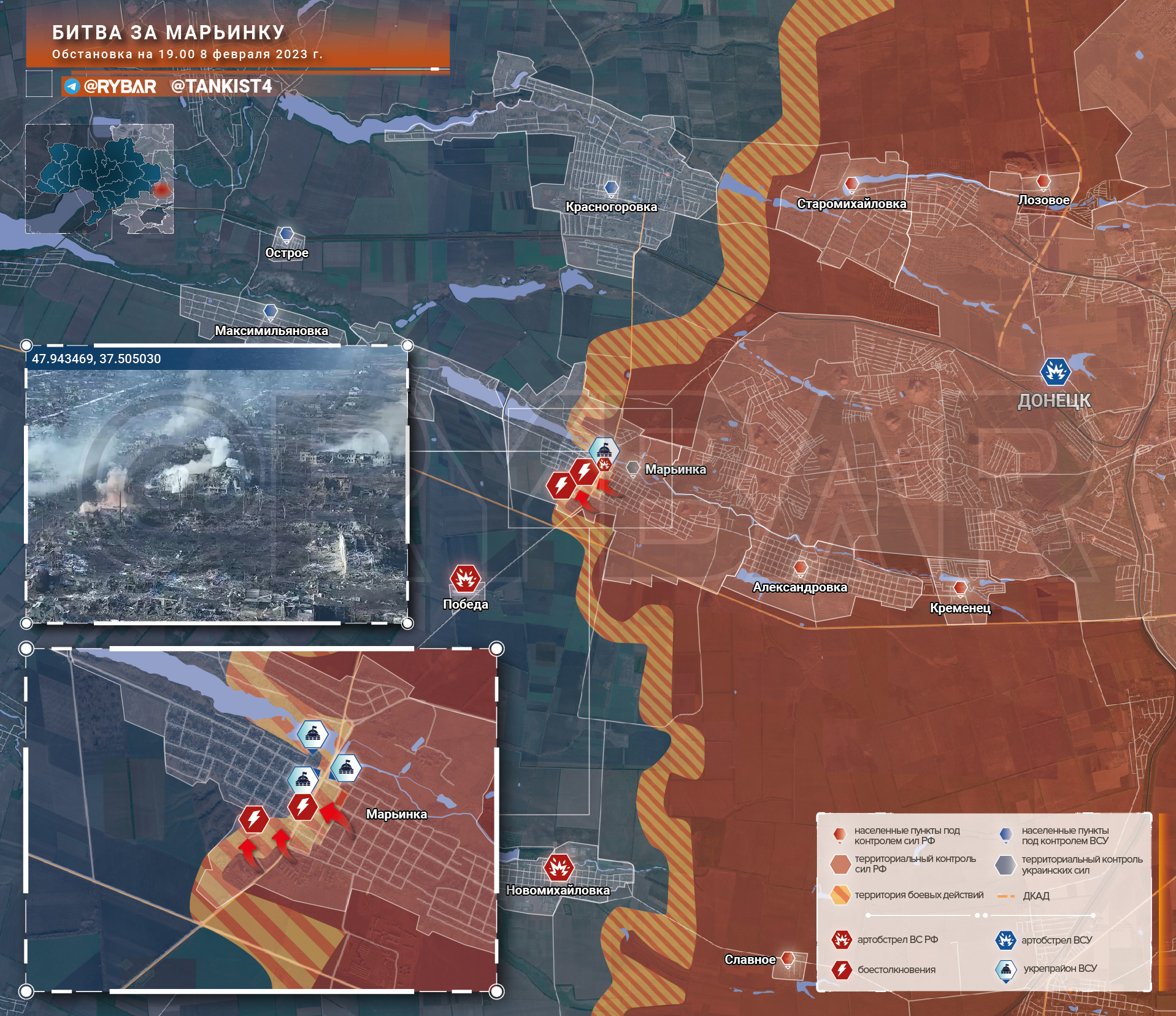

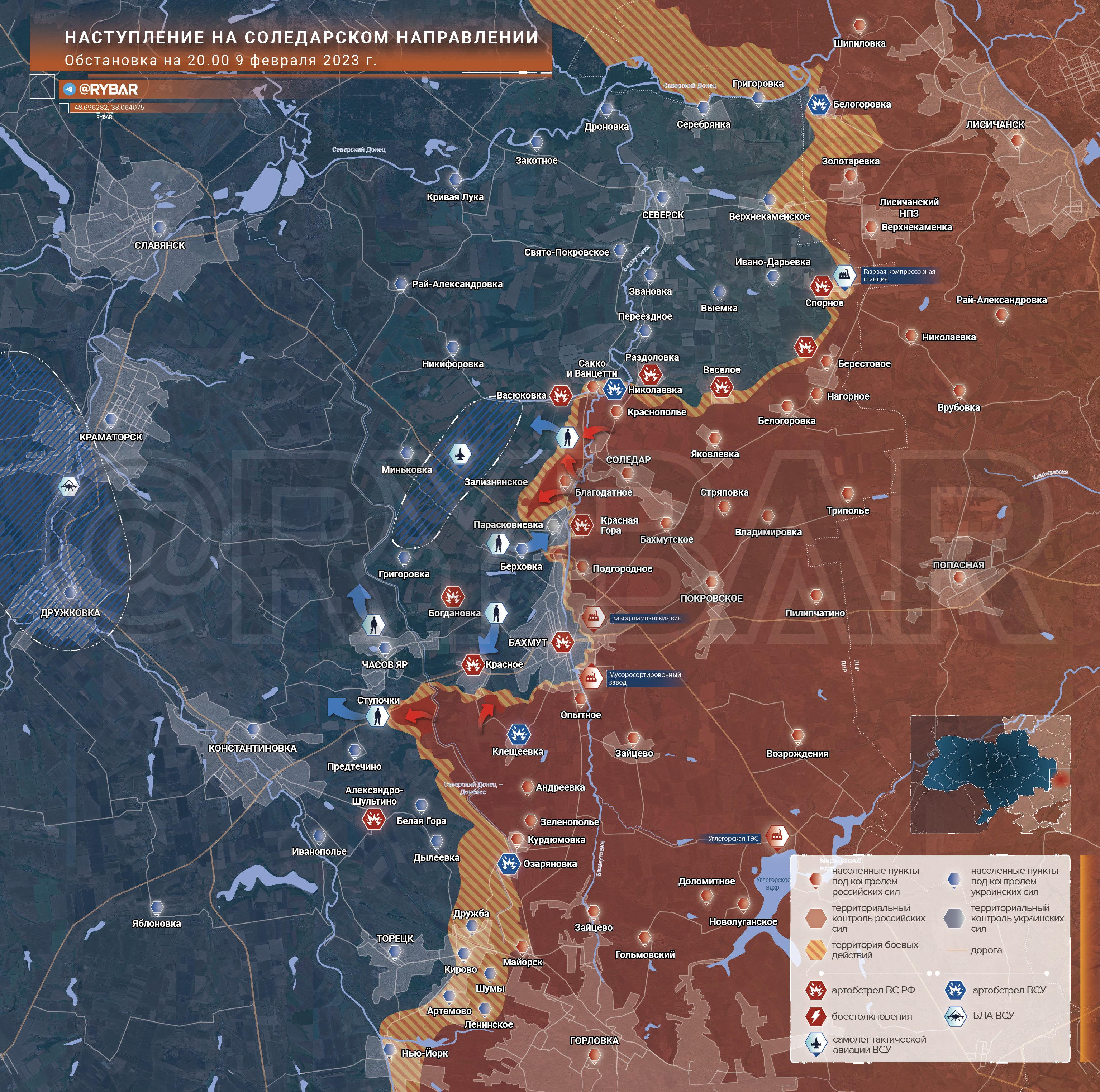

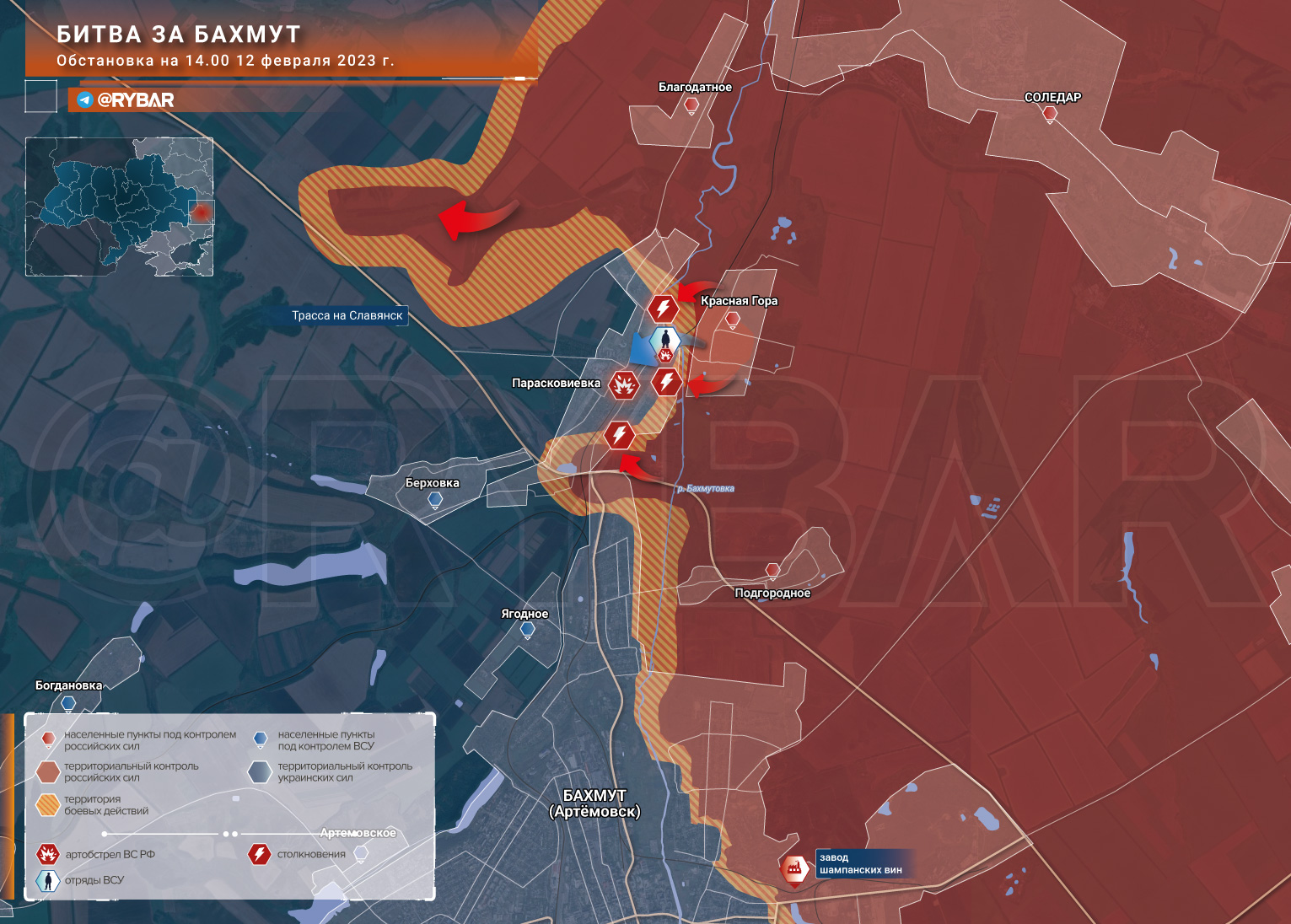

According to the situation in the Artemovsky direction.

1. Red Mountain has not yet been taken. There is progress both in the village itself and to the south of it. The situation for the remaining garrison is deteriorating.

2. There is also limited progress in Paraskoviewka. The enemy is resisting there in an organized manner. We don't drop our hats ahead of time.

3. There is also an advance along the northern outskirts of Artemovsk. Here our troops are striving, on the one hand, to advance in the direction of the last road to Artemovsk and, having pulled up artillery, take it under fire control. On the other hand, actions north and south of Krasnaya Gora demonstrate the desire to cut the supply lines of the enemy forces defending in Krasnaya Gora and Paraskovievka, forming a kind of mini-cauldron in the style of Gorsky and Zolotoy, which can force the enemy to abandon positions in these villages and roll back to Chasov Yar .

4. The fall of Paraskovievka and Krasnaya Gora will make the abandonment of Artemovsk by the enemy inevitable, since the threat of operational encirclement will become a pressure factor.

5. It is also worth noting that the pressure of our troops in the direction of Chasov Yar and Krasny is intensifying. The road through Krasnoye is not accessible for use due to constant artillery fire.

***

Colonelcassad

Seriously, Prigozhin’s trolling of Zelensky, with calls to “fight to the end for Artemovsk” and “arrange an air battle”, in addition to PR issues for Prigozhin himself and the Wagner PMC, touches on an extremely sensitive issue for Ukraine, where, on the one hand, the continuation of the battle for Artemovsk , which Prigozhin calls for, is associated with a further increase in the off-scale losses of the Artemov group and the tying up of the operational reserves of the Armed Forces of Ukraine in the Artemov direction, which could be used both for counterattacks in other sectors and for deterring the expected Russian offensive.

And the retreat of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, in turn, will look like weakness, after all the months of propaganda about the "Artemivsk fortress" and "not a single Ukrainian city will be surrendered." In the eyes of the layman, it will look as if Prigozhin offered Zelensky to continue the battle, and Zelensky ran away from Artemovsk. Here, Prigozhin simply strikes at the wea

***

Colonelcassad

Today or tomorrow in Ukraine are expected:

1. Extension of martial law for another 90 days.

2. Extension of the forced general mobilization regime for another 90 days. The hunt for people will continue.

3. The resignation of the current Minister of Defense Reznikov (the consequences of a corruption scandal with massive and large-scale theft and cuts in the MOU) and the appointment of the head of the GUR Budanov instead.

4. Approval of the head of the SBU Malyuk in his position.

https://t.me/s/boris_rozhin

Google Translator

**********

The Fight for Ugledar

Posted by INTERNATIONALIST 360° on FEBRUARY 6, 2023

Vladislav Ugolny

Russian servicemen are seen as they fire from 2A18 D-30 howitzers toward Ukrainian positions in the course of Russia’s military operation in Ukraine, at the unknown location. © Sputnik / RIA News

Why controlling a small town in southwestern Donbass is so important for the Russian military

After the successful capture of Soledar, Russia has continued to advance in Donbass, with battles ongoing. To the southwest, Ugledar – a small mining town a hundred kilometers north of Mariupol – has become the main contact point for Moscow’s troops. If the Russians succeed in this offensive, it will be a significant blow to Ukraine. Potentially, a victory in Ugledar could change the balance of power in the Donetsk area and improve Melitopol’s defenses.

Why is there such a focus on this area?

Another assault on Ugledar was launched on January 24 by Pacific Fleet Marines and special forces from the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR). Although Russia made some gains in the early days of the operation and Ukrainian forces suffered heavy losses, little progress has been made in terms of land.

Ugledar is made up of a combination of four blocks of 1960s Soviet-era panel-built multi-story buildings. It differs from more traditional cities in that there are no private houses within the city limits. This makes Ugledar a compact fortress, not only on an elevated site, but with an additional 27 meters of built-up fortification.

These factors have made Ugledar a key part of the Ukrainian defense in southwest Donetsk. Kiev’s continued control of these positions allows its forces to have a grip on the surrounding area, preventing Russians from flanking Marinka, Kurakhovo, and Avdeevka from the south. Also near Ugledar is an important section of the Donetsk-Volnovakha railway line, and the presence of Ukrainian troops near it prevents it from being used for military purposes.

Ugledar, Yuzhno-Donbasskaya mine. © Wikipedia

This is not Moscow’s first attempt to occupy the city

The Russian Army’s first two offensives on Ugledar were unsuccessful. The current front line began to take shape in March last year, after DPR troops broke through Ukrainian defenses at Volnovakha and Granitnoye to link up with Russian forces coming from Crimea. They achieved the strategic task of encircling Mariupol and creating a land corridor between Crimea and Rostov-on-Don. However, the battle for Mariupol delayed the Russian forces and prevented them from taking Ugledar and Velikaya Novoselka to the west.

For a long time, this section of the front was the scene of trench warfare and artillery duels. It placed the inhabitants of the villages in the area in a difficult position, dependent on humanitarian aid, the delivery of which was accompanied by regular shelling. A monastery in the village of Nikolskoye, near Ugledar, had become something of a humanitarian hub and shelter. However, it too was regularly bombed.

On June 22, the Ukrainian forces launched a counter-attack south of Ugledar, using their control of the high ground to occupy the village of Pavlovka. They failed to advance further than the village of Yegorovka, but this counter-attack was the beginning of a long period of positional fighting to the point of exhaustion. Battles continued throughout the summer in the forest belt between Pavlovka and Yegorovka. Both sides suffered heavy casualties, but the front line remained static until the end of October, when the Russians tried to retake Pavlovka.

This attack was not fully thought through. Although the battlefield eventually fell to the Russians, launching an offensive in muddy conditions was not a good idea. The attack on Pavlovka resulted in losses of armored vehicles and was accompanied by difficulties in evacuating the wounded and bringing in reinforcements. As a result, after about ten days of fighting, Pavlovka, below Ugledar, was under the Russian flag, but it wasn’t possible to continue the offensive further north. This experience was widely discussed in the military section of the Russian media, and the generals in charge were heavily criticized.

How the battles are going

Two months later, having prepared their forces for a sudden surge, the Russians launched a third battle for Ugledar. According to DPR official Aleksandr Khodakovsky, who took part in the fighting as part of a police unit, aerial images showed considerable confusion and disorganization in the enemy ranks.

RTSuccess was achieved with a breakthrough from the southeast through a dacha village near Nikolskoye, while the Ukrainians had based their defenses on the expectation of an attack from Pavlovka. As a result, within a few days, the Russians had taken control of the dachas near Nikolskoye, the farms and the granary north of Pavlovka, and entered the southeastern outskirts of Ugledar.

Kiev’s forces, in turn, restructured their defenses by retreating deeper into Ugledar and continuing to use the panel houses as strongholds. The Ukrainian military made the area of the Yuzhno-Donbasskaya Mine No. 1, northeast of Ugledar, the main concentration of reserves for counter-offensive actions.

Units of the 1st Tank Brigade, 35th Marine Division, and according to unconfirmed reports, the 80th Airborne Assault Brigade, were sent in to support the Ukrainians fighting there, in the 72nd Mechanized and 68th Yager Brigades. Thus, despite the lack of meaningful progress and a return to positional fighting, the Russians succeeded in straining Ukrainian reserves and moving them further away from Artemovsk/Bakhmut and Kremennaya, where the Russian offensive is now underway.

As of now, attempts by the Russian military to advance near Ugledar are continuing. According to an adviser to the acting head of the DPR, Igor Kimakovsky, the settlement is partially surrounded.

Even in the event of success at Ugledar, a significant push by the Russian Army northwards is unlikely because it would be difficult once Ukraine has moved in reserves. However, Kiev would lose its key stronghold in the area and would be forced to retreat northward, losing a convenient bridgehead for an offensive against the Donetsk-Volnovakha highway and key positions for artillery.

https://libya360.wordpress.com/2023/02/ ... r-ugledar/