Posted on October 15, 2024 by Yves Smith

Yves here. Israel’s barbaric conduct of its wars, the deteriorating situation in Ukraine, and the hard-fought US presidential election have been dominating the news. That makes it way too easy for legitimately important stories to go by the wayside, particularly ones involving scams. Blue hydrogen is one of the far too many supposed climate easy fixes that are taken up by promoters and sold as far more effective than they are (keep in mind that overstated impact justifies overspending).

But blue hydrogen, as DeSmog explains below, looks far more cynical than that. A pet initiative of fossil fuel companies, its backers are trying to claim it should get “low carbon” subsidies. DeSmog’s analysis shows that, based on the performance of existing projects, it should not qualify.

By Aline Nippert. Originally published at DeSmogBlog. This is the fourth part of a DeSmog series on carbon capture and was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe and published in partnership with Le Monde

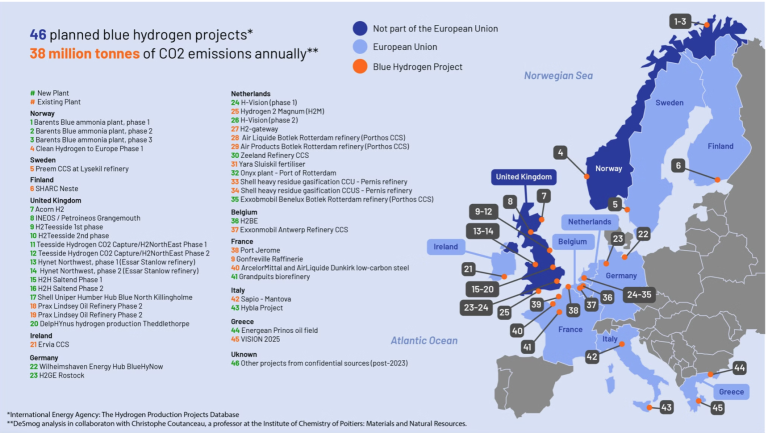

Billed by the fossil fuel industry as a climate solution, dozens of planned blue hydrogen projects in Europe could consume more natural gas each year than France, and produce emissions on a par with Denmark, a DeSmog analysis has found.

The findings raise new questions over blue hydrogen’s climate impact as EU officials deliberate over technical standards that could allow the technology to count as “low-carbon” — and thus qualify for billions of euros in subsidies.

The term blue hydrogen is used to describe hydrogen made from natural gas, where carbon capture and storage(CCS) technology is deployed to trap much of the large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) generated during the production process, then bury it underground.

Hydrogen emits no CO2 at the point of use. If produced cleanly, the molecule is theoretically capable of decarbonising various sectors, including chemicals and petrochemicals, steel, cement, power, road transport and potentially aviation.

Although Europe has yet to produce any blue hydrogen at scale, Shell, BP, Equinor, TotalEnergies, Eni, and ExxonMobil are among dozens of oil and gas companies promoting the technology as a way of meeting climate goals.

However, industry has yet to provide the kind of comprehensive data needed to estimate how far any possible climate benefits from switching to blue hydrogen produced by the planned projects may offset the residual CO2 emissions and methane leaks associated with making it.

To begin to fill this gap, DeSmog teamed up with Christophe Coutanceau, a professor at the Institute of Chemistry of Poitiers: Materials and Natural Resources, and co-lead of a hydrogen working group at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, known by its French acronym CNRS. [Details of the methodology used can be found at the end of this story].

By reviewing extensive industry reports and technical data on 46 proposed blue hydrogen projects in the EU, UK and Norway listed by the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA), DeSmog found that 27 involve building new hydrogen production facilities. Another 15 envisage retrofitting existing hydrogen plants with carbon capture, while the status of four remained undetermined. More than a third of the total volume of hydrogen gas produced by these 46 projects would be used for oil refining — the main use of hydrogen today, according to a DeSmog tally of available data.

In collaboration with Coutanceau, DeSmog estimated that these 27 new blue hydrogen facilities could consume 48 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas each year — about a tenth of the total consumption in the EU, UK and Norway in 2022 (499 bcm), and more than the annual amount of gas burned in France (38 bcm).

DeSmog’s analysis estimated the total annual emissions associated with the 46 planned blue hydrogen projects at 38 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) — about as much as Denmark or Switzerland emitted in 2022 (42 million tonnes of CO2). Our calculations factored in methane leaks in the natural gas supply chain and the partial efficiency of carbon capture units.

A further 33 million tonnes of CO2 could be released while the plants are being built in the one-off process used to manufacture the amine-based solvent used in the most common types of capture units, the analysis found.

“We should be very cautious with blue hydrogen. We should not buy into a false sense of complacency that it is a low-carbon fuel,” said Lorenzo Sani, power analyst at financial think tank Carbon Tracker, who reviewed DeSmog’s methodology and findings. “A badly managed development of blue hydrogen will increase carbon emissions while creating new gas demand that risks extending energy security concerns.”

The concerns were echoed by Paul Martin, a chemical engineer and decarbonisation consultant at Spitfire Research, who also reviewed the findings.

“This analysis confirms the fact that so-called ‘blue’ hydrogen is rather ‘blackish blue’,” Martin said. “Even technological innovations in the field of hydrogen production from fossil gas don’t change this.”

Coutanceau, the CNRS hydrogen expert, underscored the huge scale of the task fossil fuel companies face in realising plans to sequester the captured CO2 in disused oilfields in the North Sea.

“In addition to the tens of million tonnes of CO2 equivalent that blue hydrogen projects would release every year, what are we going to do with the captured CO2?” Coutanceau said. “There’s talk of underground storage in saline cavities, but to my knowledge this infrastructure doesn’t yet exist on an industrial scale.”

In April, workers began boring a hole under the seawall at the Port of Rotterdam, marking the start of construction of the Porthos carbon capture and storage project — which aims to start sequestering CO2 captured at two planned blue hydrogen projects in a disused offshore gas field from 2026.

Equinor, Shell and TotalEnergies plan to store millions of tonnes of CO2 under the North Sea in their Northern Lights joint venture, which opened a storage facility near Bergen last month. Equinor says the project will initially store 1.5 million tonnes of CO2 a year — with that capacity already committed to ammonia, cement and bioenergy plants.

Lack of Data

Hydrogen Europe, an industry association grouping hundreds of companies — ranging from Shell and BP, to utilities and engineering firms — dismissed concerns over the potential emissions footprint of the planned blue hydrogen projects, saying substituting blue hydrogen for fossil fuels would have a net climate benefit.

“You want me to admit that we have a lot of CO2 emissions because of blue [hydrogen]. That’s not true,” Jorgo Chatzimarkakis, Hydrogen Europe’s CEO, told DeSmog in an interview. “You have to look at the big picture: With blue hydrogen, there will be fewer CO2 emissions than if you used natural gas as your [source of fuel]. You criticize the fact that we’re reducing emissions. I don’t understand the logic.”

According to the Hydrogen Council, a global trade association, producing one kilogram of blue hydrogen using natural gas and a high level of capture (90 to 98 percent) would emit a maximum of 3.9 kilograms of CO2 — 70 percent less than a conventional hydrogen plant.

However, it’s difficult to independently estimate the decarbonisation potential of the planned blue hydrogen projects without access to data showing how the gas will be used, and thus how far it might reduce demand for fossil fuels.

“For now, we don’t have enough data,” Coutanceau said. “To arrive at a precise calculation of avoided emissions, we’d need to know whether the hydrogen would be used as a feedstock in a manufacturing process, to produce heat, or used in fuel cells to produce electricity. It’s not the same [decarbonisation] gain.”

Hydrogen Europe declined to respond to DeSmog’s request for an estimate for the quantity of CO2 emissions that could be saved by the 46 proposed blue hydrogen projects. The Global CCS Institute, an oil and gas industry body, did not respond to a request for comment.

Regarded as one of the most authoritative models for decarbonising the energy system, the IEA’s Net Zero by 2050 Roadmap sees an increase in global blue hydrogen production capacity to 18 million tonnes (Mt) by 2030 from the negligible amounts produced today. But the 46 planned blue hydrogen projects in Europe alone would produce 10 million tonnes of blue hydrogen — or more than half the global total needed in the IEA scenario, DeSmog found.

Only a handful of the proposed projects have received a final investment decision, meaning there is no guarantee they will all be built. Nevertheless, climate advocates say the discrepancy between the scale of the proposed build-out, and the Net Zero 2050 roadmap, raises questions over whether industry is intent on using blue hydrogen to preserve demand for natural gas, even as Europe transitions away from fossil fuels.

Make-or-Break Moment’

Fossil fuel companies, utilities and industrial gas producers are vying for a share of a cumulative total of $100 billion in state support for hydrogen projects that had been announced by EU member states and other European countries by 2023, according to data from BloombergNEF.

Some climate groups are urging governments to back “green” hydrogen — the term used for hydrogen produced in an emissions-free but energy-intensive process powered by wind and solar. In contrast to blue hydrogen’s reliance on natural gas as a feedstock, green hydrogen is made using large quantities of water.

The EU has set up Hydrogen Bank to help scale up the technology, with the Renewable Energy Directive stipulatingthat 42 percent of hydrogen used in industry will have to be produced solely from renewable energy sources by 2030, and 60 percent by 2035.

But environmental groups are concerned that industry lobbyists may convince the European Commission to shift those obligations from green hydrogen to a more loosely defined “low-carbon” hydrogen — which would include blue hydrogen projects. That could crowd out investment in green hydrogen, which is much costlier to produce.

“If selection is based solely on price, since blue hydrogen will be cheaper than green hydrogen, blue hydrogen projects will [win out] and will make green hydrogen disappear,” Geert De Cock, electricity and energy manager at Transport & Environment, a Brussels-based research and advocacy group, told DeSmog. “In my opinion, this is a frontal attack on green hydrogen.”

In April, Transport & Environment and other environmental groups, joined by wind and solar companies, wrote an open letter urging the European Commission to adopt a “robust definition” for low-carbon hydrogen, with stringent conditions attached to blue hydrogen production.

The Renewable Hydrogen Coalition, environmental tank Bellona, and the Environmental Defense Fund were among signatories urging Commissioner for Energy Kadri Simson and Commission Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič to ensure the new rules reflected the entirety of greenhouse gas emissions associated with a particular blue hydrogen project; set a minimum rate of carbon capture; and set maximum rates for methane leakage.

The letter’s signatories also call for a guarantee that any blue hydrogen to qualify as “low-carbon”, “will only be produced from existing (not additional) gas production capacity”.

“If the rules are sufficiently strict, the new [blue hydrogen] projects will not happen,” De Cock said. “It is really make-or-break for the industry.”

Betting on Blue

Today, almost all industrial hydrogen is of the “grey” variety, where the CO2 emitted during the process of making it from natural gas is vented into the atmosphere, accounting for about two percent of global CO2 emissions, according to the IEA. About half of this hydrogen is used in oil refining, where the gas is used to strip sulphur from refined products, and make diesel and other oils.

Some climate advocates suspect that the fossil fuel industry is backing blue hydrogen in part because the resulting demand for natural gas will serve to prolong the useful life of existing gas deposits, drilling rigs, pipelines and other infrastructure. That could reduce the risk that the EU’s goal to slash carbon emissions by 55 percent by 2030 will saddle oil and gas companies with billions of euros of stranded assets.

In the Netherlands, site of 12 of the 46 proposed blue hydrogen projects, U.S. industrial gases company Air Products and French rival Air Liquide have announced plans to retrofit their existing grey hydrogen plants in the Port of Rotterdam with carbon capture equipment to produce blue hydrogen. “Hydrogen plays a critical role in the energy transition and in mitigating the effects of climate change,” Air Products says on its website.

The captured CO2 will be handled by Porthos, a joint venture between state-owned firms Energie Beheer Nederland, Gasunie, and the Port of Rotterdam Authority. The project aims to store 2.5 million tonnes of CO2 captured annually from various industries in depleted gas fields under the North Sea for 15 years, starting in 2026.

Elsewhere in the Netherlands, in the maritime province of Zeeland, Air Liquide is building a new plant to supply blue hydrogen to Zeeland Refinery, a joint venture between TotalEnergies and Russia’s Lukoil. Air Liquide is also participating in the Kairos@C project in the Belgian port of Antwerp, which aims to capture more than 14 million tonnes of CO2 over its first 10 years of operations, including from two blue hydrogen plants.

“The Group has a complete portfolio of technological solutions and services to support the decarbonisation of its customers around the world,” Air Liquide said in its 2022 strategic plan.

American-German gas manufacturer Linde, which is headquartered in the UK, also sees blue hydrogen as a growth opportunity. “Blue hydrogen is the next step,” the company says on its web page. “Gray and blue hydrogen are important stepping stones on the path to green hydrogen as they will allow for the necessary frameworks and infrastructures to be developed while green hydrogen production reaches the necessary scale.”

Oil Companies Spy Opportunities

The track record of the fewer than 10 existing commercial blue hydrogen plants in operation has been uneven. For example, Shell’s Quest project in Canada, capable of producing 900 tonnes of hydrogen a day, captured five million tonnes of CO2 from 2015-2021 — but released more than 7.5 million tonnes of greenhouse gases during the same period, according to a report based on official data collated by Global Witness.

Nevertheless, oil companies are talking up the benefits of blue hydrogen, with TotalEnergies, Eni, Shell and BP all characterising the gas as a clean fuel that can be used to bridge the gap before green hydrogen becomes more economical.

In January last year, Norway’s state-owned oil company Equinor signed a memorandum of understanding with the German energy provider RWE to jointly develop blue hydrogen projects in Norway for export via pipeline to Germany. Equinor announced last month that it had scrapped the plans, citing excessive costs and insufficient demand.

In the UK, site of 14 of the 46 blue hydrogen projects on the drawing board, BP is developing a large-scale blue hydrogen plant, called H2 Teesside. The project aims to produce 160,000 tonnes of blue hydrogen a year, with the developers pledging to capture two million tonnes of associated CO2 emissions and bury them under the North Sea.

“The project is already well advanced,” said Sani, the power analyst at Carbon Tracker, and author of a June reporton blue hydrogen in the UK. “Although the final investment decision has not yet been taken, several agreements have already been concluded, and the construction of a new [liquefied natural gas] terminal to supply the plant with fossil gas has been proposed.”

Meanwhile, U.S. major ExxonMobil, which has various carbon capture interests in the Netherlands, Belgium and UK, describes blue hydrogen as “one of the few proven technologies that could deliver significant reductions in CO2 emissions in high-emitting, hard-to-decarbonise sectors.”

Battle of Perceptions

Industry groups are keen to kick-start the planned blue hydrogen projects by portraying them as equivalent to their green hydrogen rivals — downplaying the differences in the emissions footprint of the technologies, and focusing on economics.

“It’s about decarbonisation, it’s not about colour,” said Chatzimarkakis, the Hydrogen Europe CEO, reiterating a position commonly advanced by industry. “If we start to criticize technologies that help to decarbonise, to the energy transition, we’re making a big mistake. We need to be ‘technology diverse’. We need to have every technology that allows for CO2 abatement to play its role.”

Under existing EU rules, the maximum threshold of greenhouse gas emission for hydrogen to be considered “low-carbon” is equivalent to that of green hydrogen: 3.38 kilograms of CO2e per kilogram of hydrogen. But whether or not a particular blue hydrogen facility meets that definition depends on the methodology used to calculate its emissions.

In May, the EU adopted a raft of new rules on gas and hydrogen under its Green Deal climate framework — and tasked officials with developing a methodology for determining which hydrogen projects count as “low-carbon” within a year. The European Commission published a draft of the new rules on September 27, and opened a month-long public consultation.

The draft proposed that blue hydrogen projects should be subjected to a “full life-cycle analysis” — meaning that emissions estimates would include factors such as methane leakages during the production and transport of the natural gas, and stringent rules for assessing carbon capture rates.

But the devil is in the details, campaigners say.

In a response to the draft, Transport & Environment questioned the rigour of proposed measures to factor in methane leakages, while Bellona noted a lack of measures to deter the build-out of new natural gas infrastructure.

Many more questions remain unanswered.

The draft suggests that all emissions associated with the process of capturing CO2, then transporting the gas and injecting into undersea storage sites, will be taken into account when measuring the carbon footprint of a blue hydrogen project. But the rules are silent on the question of whether the emissions associated with the production of the amine-based solvent needed to operate the most common carbon capture technology should also be factored in.

It has also yet to be determined how to account for likely leaks of hydrogen — which is considered an “indirect” greenhouse gas because it causes chemical reactions that affect concentrations of methane, ozone, and stratospheric water vapor, as well as aerosols. Other questions include: How will the natural gas supply chain be certified? And how to ensure such certifications are accurate? Would it make more sense to calculate the warming impact of the methane over a period of 20 years (84 times greater than CO2), as advocated by environmental groups, or 100 years (28 times greater), as desired by industry?

“European policymakers need to set strong guarantees for blue hydrogen projects, as they risk derailing net zero strategies if they are developed without addressing supply chain emissions,” said Carbon Tracker’s Sani. “Without stringent regulatory frameworks, blue hydrogen could inadvertently become a setback in our fight against climate change.”

Variations in the methane leakage rates in different gas-producing regions further complicate efforts to calculate blue hydrogen’s carbon footprint.

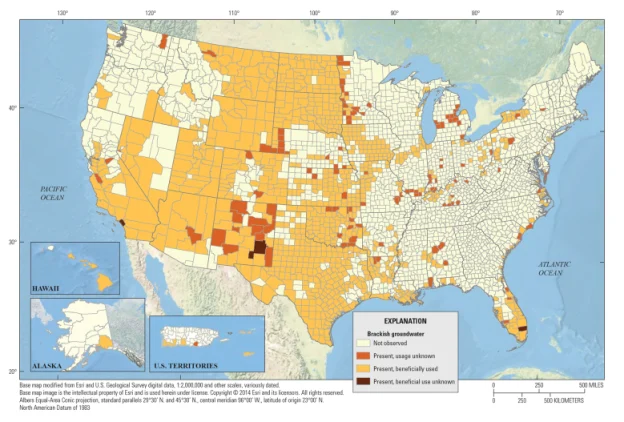

Norway’s gas industry is said to limit its leakage rates to below 1.0 percent — less than the estimated global average of 1.4 to 2.0 percent. However, with Norway’s gas production committed to existing customers, it seems likely that future blue hydrogen projects will turn to suppliers such as the United States, where shale oil and gas reserves are being massively exploited, and estimates for the proportion of methane molecules escaping into the air can be 3.5 percent, or higher. In some parts of the U.S., such as the Permian Basin in New Mexico, leakage rates above 9.0 percent have been recorded — meaning that even within a given country, where the gas comes from can have a big impact on the level of climate harm.

Chatzimarkakis, of Hydrogen Europe, said the origin of the natural gas was outside the scope of his group’s remit. “I don’t know where the gas will come from,” he said. “We are not a gas lobby. That’s not our business.”

Aline Nippert’s new book Hydrogen Mania: An Investigation into the Totem of Green Growth is published in French by Le passager clandestin.

Additional reporting by Michael Buchsbaum and Sharon Kelly

Methodology and Assumptions[/i]

We began by examining the 51 proposed blue hydrogen projects in the EU, UK and Norway featured in a databasemaintained by the International Energy Agency (data current as of October 2023). We excluded four projects in the UK that have been canceled (H2 Leeds City Gate project; Cavendish Phases 1 and 2; and a project at the Fawley refinery) and one in Norway (Aukra CCS). To simplify the calculations, we assumed that all the projects used natural gas, commonly used to make hydrogen in Europe. (Hydrogen can also be produced from oil and coal).

Project by project, we trawled specialised websites, press releases, and technical reports to ascertain whether the developers were planning to retrofit an existing grey hydrogen plant to produce blue hydrogen — or build a new blue hydrogen plant from scratch.

We found developers were planning:

15 retrofits

27 new projects

4 undetermined

Estimating Natural Gas Consumption

We used the developer’s projections for how much blue hydrogen a given plant would produce each year to estimate how much natural gas it would consume.

We used a standard assumption that it takes 3.6 kilograms of methane (the main ingredient of natural gas) to produce 1.0 kilogram of hydrogen.

We then increased the result by 22 percent to reflect scientific estimates for the additional natural gas that would be required to power the carbon capture process. The total amount of natural gas required by the 46 plants (new plants and retrofits) was estimated at 67 billion cubic metres (bcm).

We concluded that the planned 27 new blue hydrogen facilities would consume a total of 48 billion bcm of natural gas each year as a feedstock — about a tenth of the total consumption in the EU, UK and Norway in 2022 (499 bcm), and more than the amount of gas burned in France (38 bcm).

Estimating CO2 Emissions

To estimate the amount of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) associated with the 46 planned blue hydrogen projects, we took various factors into account:

The amount of CO2 that would be emitted directly each year during the process of producing blue hydrogen, which is a factor of the average efficiency of the capture equipment (either 60 percent or 90 percent depending on the type of production process): 18 million tonnes.

The amount of CO2e escaping into the atmosphere each year as a result of methane leaks during the process of extracting, storing and transporting the natural gas. (Between 20 and 48 million tonnes of CO2e for leakage rates of 1.5 percent and 3.5 percent respectively).

The amount of CO2 generated by the one-off production of the amine-based solvent used in most carbon capture units: (33 million tonnes). Since the solvent can be reused, the emissions associated with solvent production will only occur when the plants are being built.

In all, we estimated that building all 46 blue hydrogen projects would lead to the minimum release of 38 million tonnes of CO2e every year — on a par with Denmark’s annual emissions of 42 million tonnes.

Here is a more detailed breakdown of each stage of our calculations:

Carbon Capture Efficiency

Under existing blue hydrogen technology, about 40 to 60 percent of the CO2 molecules present in a given volume of flue gas are captured, according to the IEA. We therefore estimated a 60-percent capture rate for the 15 retrofit projects.

For the 27 new-build projects, we assumed 90 percent efficiency, in line with industry projections for next generation capture technologies.

Multiplying the total amount of CO2 released during the production process by the percentage capture rate (90 percent for new plants; 60 percent for retrofits) leads to 18 million tonnes of CO2 emissions.

Amine-based Solvent

The most common carbon capture technologies rely on an ammonia-derived solvent to absorb CO2 molecules in the flue gases. We calculated the one-off emissions associated with the necessary ammonia production at 33 million tonnes of CO2, using the following assumptions:

Producing 1.0 tonnes of ammonia generates 2.4 tonnes of CO2 .

250 kilograms of ammonia are required to produce 1.0 tonne of solvent

1.4 tonnes of solvent are needed to capture 1.0 tonne of CO2

Note: We excluded the nine blue hydrogen projects involving Air Liquide, whose Crypocap carbon capture technology does not rely on an amine-based solvent.

Industry says it is working to decarbonise ammonia production by using blue hydrogen as a feedstock. However, only four of the 46 proposed blue hydrogen projects are designed to produce ammonia.

Methane Leakage

To convert the likely quantity of methane leakage associated with the projects into CO2e, we multiplied the quantity of methane by a factor known as Global Warming Potential (GWP).

Methane exerts a greater warming effect in the short term, before it gradually breaks down. That means its GWP is higher over a 20-year horizon (84 times greater than that of CO2) than a 100-year horizon (28 times greater).

Estimates for the amount of methane that leaks during the extraction, transport and storage of the natural gas used to make blue hydrogen vary widely, depending on the origin of the gas.

Conservatively, assuming a leakage rate of 1.5 percent (and a GWP of 28 over a 100-year horizon), the emissions due to methane leaks associated with the natural gas used to feed the 46 projects equal 20 million tonnes of CO2e per year.

Less conservatively, assuming a 3.5 percent leakage rate (and a GWP of 28), this figure more than doubles to 48 million tonnes of CO2e per year.

Under various assumptions, the methane leakage associated with the 46 blue hydrogen projects could range from 20 million tonnes of CO2e (leakage rate of 1.5 percent and GWP of 28) to 117 million tonnes of CO2e (leakage rate of 3.5 percent and GWP of 84).

Expert Review

DeSmog’s analysis was carried out earlier this year in collaboration with Christophe Coutanceau, a professor at the Institute of Chemistry of Poitiers: Materials and Natural Resources, and co-lead of a hydrogen working group at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, known by its French acronym CNRS.

Power analyst Lorenzo Sani, who has carried out similar work on blue hydrogen projects in the UK for Carbon Tracker, and Paul Martin, chemical engineer and decarbonisation consultant at Spitfire Research, reviewed our methodology and findings.

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2024/10 ... nmark.html

******

Climate activists protesting forest biomass outside a conference at the World Forestry Center in Portland, Oregon last month. (WNV/Nick Englefried)

West Coast climate activists battle the false ‘solution’ of forest biomass

Originally published: Waging Nonviolence on October 8, 2024 by Nick Engelfried (more by Waging Nonviolence) | (Posted Oct 15, 2024)

“Who will own the forests? Who will own the sky?” sang dozens of umbrella-wielding protesters as rain drizzled outside the World Forestry Center in Portland, Oregon on Sept. 25. Inside the building, timber company representatives, investors and others involved in deciding the fate of forest ecosystems were meeting for an event called CANOPY: Forests + Markets + Society.

Billed as “the premier annual event on institutional forestland investing,” CANOPY is a conference whose 2023 attendees included Weyerhaeuser, Boise Cascades, biomass energy giant Drax and J.P. Morgan. It was formerly called “Who Will Own the Forests?” and has drawn criticism from climate groups concerned about its focus on corporate and investor-led approaches to forest management. Last year, climate activists blockaded entrances to the event’s opening reception for over an hour.

Organizers of the 2024 conference not only changed the name, but erected chain-link fencing around the World Forestry Center to keep out anyone unable to pay the $1,660 registration fee.

“The title of the event has changed, but the conference has not,” Brenna Bell, forest campaign manager for 350-PDX, told the crowd chanting in the rain outside.

At it’s root this is a capitalist event, and the so-called climate solutions being promoted here are Wall Street backed and funded.

Bell is part of the growing movement to defend forests from industries that hope to turn a profit by investing in carbon-dense ecosystems during the transition away from fossil fuels. Examples include firms involved in the controversial practice of buying forestlands as carbon “offsets,” and those trying to turn trees into “renewable” biomass energy. This last point is especially relevant for West Coast communities.

Global energy companies are currently pushing to build at least four major biomass pellet plants along the West Coast: two in Washington and two in California. The rhetoric they use to describe these projects includes phrases like “carbon neutral” and “renewable energy,” terms also featured prominently at the CANOPY conference.

However, for communities that will bear the brunt of the forest biomass industry’s environmental impacts, the benefits of these types of projects are far less clear than they appear in the rosy picture painted at CANOPY. In fact, up and down the West Coast the burgeoning biomass boom threatens to derail hard-won progress on climate, ecosystem protection and environmental justice.

Brenna Bell speaking outside the forestry industry event in Portland last month. (WNV/Nick Engelfried)

Burning forests

Gloria Alonso Cruz had recently started a job as the environmental justice advocacy coordinator for Little Manila Rising, a grassroots organization in South Stockton, California, when she heard that a company called Golden State Natural Resources wanted to build a wood pellet storage and export facility in the community.

“They hadn’t provided many details,” Alonso Cruz said.

But I attended a scoping meeting the company was putting on. All I knew going in was this was a project having to do with vegetation management that would lead to shipments coming through Stockton.

To Alonso Cruz’s surprise, the virtual meeting was joined by activists from around the world, some as far away as Japan and Australia. Many spoke about negative impacts of the forest biomass industry in their countries.

“That’s how I got a more comprehensive picture of what this industry is and the greenwashing it does,” Alonso Cruz said.

In regions where the biomass industry is well established, like the U.S. South and British Columbia, forests have been denuded as companies like Maryland-based Enviva and U.K.-based Drax turned their wood into pellets. Now, Golden State Natural Resources, or GSNR, wants to build pellet plants in California’s Tuolumne and Lassen Counties.

Together, these plants would have the annual capacity to process almost two million tons of wood from forests in the Sierra Nevadas, where battles over logging have raged between environmental groups and timber companies for more than a century. Both plants would send their pellets to be exported out of the Port of Stockton.

“It would lead to more rail and truck traffic through our community, which already has some of the highest asthma rates in the country,” Alonso Cruz said.

At the other end of GSNR’s supply chain, environmental groups worry about where wood to supply the proposed plants will come from. Biomass companies typically insist they will mainly process “waste” wood like sawdust and slash leftover after logging. This claim is key to the industry’s assertion that it is an environmentally friendly, carbon neutral enterprise–a portrayal that doesn’t match the experience of communities close to where forest biomass companies have set up shop.

“I can guarantee additional logging will happen if this plant is built,” said Nick Joslin of the Mount Shasta Bioregional Ecology Center, which works to protect forests near where the Lassen County plant would be built.

They want high quality, dense wood because that gives them the biggest return on their investment. Their plant will increase logging on nearby national forest lands, and I don’t know anyone familiar with the project who’d say otherwise.

Logs awaiting export at the port of Longview. (CC/Sam Beebe)

In 2022, a whistleblower accused biomass company Enviva of turning large, whole trees into pellets in North Carolina, in violation of its own sustainability policies. In 2022, the BBC documented another biomass giant, Drax, sourcing trees for its mills from British Columbian old-growth forest. Drax, which has operated for years in Canada and the South, is also the main backer of a proposed pellet plant in Longview, Washington. Earlier this year, the company signed a memorandum of understanding with GSNR.

“Drax has shown themselves to be a bad actor,” Joslin said.

GSNR wants to portray themselves as a more responsible company, but they don’t have the money to bring these projects to completion on their own. So, they’ve sold out to a multinational corporation that basically does whatever it wants.

Before any biomass company can break ground on a project in California or elsewhere on the West Coast, it will need a variety of permits from state and local governments entities. Climate, forest and environmental justice groups are already rallying their supporters to engage in this permitting process.

“We’re getting members of the public to submit comments, educating the community and trying to give people a voice on this issue,” said Megan Fiske of Ebbetts Pass Forest Watch, an organization based near Tuolumne County that opposes GSNR’s project there. In Washington State, where the other two West Coast pellet plants would be located, activists are mounting similar efforts.

The grassroots movement against forest biomass taking shape up and down the coast resembles the one that successfully beat back a flood of proposals to export coal, oil and natural gas from the same region last decade. Most of those fossil fuel export projects were eventually stopped, with communities at the points of extraction, transport and export speaking out against their local pollution and global climate impacts. Today, opponents of forest biomass are building similarly diverse coalitions.

In doing so, they are pushing back against an emerging, powerful industry that is endangering forests and action on climate change, even as it claims to be furthering the clean energy transition.

Trees as energy

An irony of the push to develop forest biomass is that it’s largely a response to policies meant to combat climate change. At industry conferences like CANOPY, turning trees into energy is seen as a way for companies to take advantage of government subsidies for renewables established in European and East Asian countries.

The U.K. is perhaps the most prominent example of a country embracing biomass as a domestic energy source. Biomass is now the U.K.’s second-largest source of renewable energy, meeting 12.9 percent of the country’s electricity needs in 2021. Much of this energy comes from the massive Drax power plant in North Yorkshire, England, which last year finished fully transitioning to burn wood pellets instead of coal. Drax’s shift to wood has helped the U.K. eliminate coal from its energy mix, but at a cost to North American forests.

“This whole idea that we should cut down forests in California, use a lot of energy to send them overseas, burn the wood there, and that somehow this is a win for the climate, just doesn’t make sense,” Joslin said.

Burning trees for energy releases carbon into the atmosphere–more per unit combusted than coal, in fact. Still, biomass companies claim their product is carbon neutral because this CO2 can theoretically be reabsorbed if the trees are allowed to grow back. Even when forests harvested for biomass do regenerate, though, there is a lag time of decades during which heat-trapping gases remain in the atmosphere. This is known as the “carbon payback period,” and it is especially long when mature trees supply the fuel for biomass.

The biomass industry also argues it will remove wood from forests that would otherwise burn during Western states’ increasingly long, dry, fire seasons. However, the science on forest thinning as a means to reduce fire is inconclusive–and to the extent that it results in removing large, whole trees that are relatively fire resistant, it may actually do more harm than good.

“As someone who lives in a fire prone area myself, one of my biggest frustrations with GSNR’s project is it’s wasting time and money without fixing the real problem,” Fiske said.

Meanwhile it’s sending us backward rather than forward in terms of carbon emissions.

In certain regions of the U.S., such as the Northeast, state laws that classify biomass as clean energy have given rise to a domestic forest biomass industry. However, in most parts of the country the financial incentives to turn forests into energy come mainly from overseas. Biomass companies like Drax and GSNR don’t qualify for major subsidies under U.S. federal law–at least not yet.

Enviva Pellets Ahoskie facility in Hertford County, North Carolina. (Dogwood Alliance)

Drax competitor Enviva has submitted an application to the U.S. Treasury Department to receive clean energy tax breaks under climate provisions of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. Companies aren’t required to disclose publicly if they are applying for these incentives, so it’s unclear how many others in the biomass industry may be doing so. However, recent moves by Drax, such a decision announced last year to establish a North American headquarters in Houston, suggest the company is positioning itself to play a bigger role in the U.S. energy market.

Regardless of whether biomass companies eventually receive additional subsidies for generating “clean” energy in the U.S., the fight over industrialization of forestlands in the name of climate solutions is shaping up to be a major front for the climate movement on the West Coast in the years ahead.

“Now that Drax is involved, they can take advantage of global financing and private equity to support their biomass projects,” Joslin said.

To them, this is just a money-making deal for investors. It’s not about the health of forests or the climate at all.

https://mronline.org/2024/10/15/west-co ... t-biomass/

*****

CovertAction Bulletin: A Handful of Billionaires are Causing Climate Chaos for the World

By Rachel Hu and Chris Garaffa - October 16, 2024 0

CLICK HERE to listen on podcast platforms worldwide https://linktr.ee/CovertActionBulletin

Hurricane Milton approached the physical limits of what a hurricane can be before it made landfall, and this was driven in part by the fact that 13 major Western corporations are responsible for the deforestation of 17% of the Amazon rainforest over the last few decades.

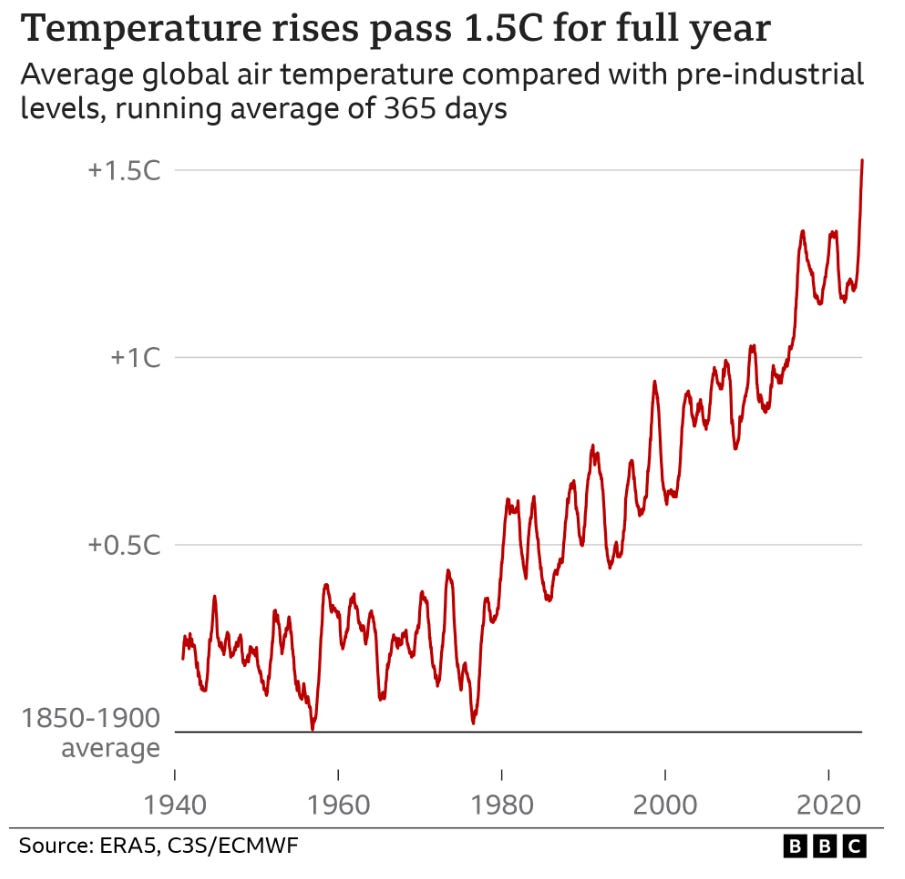

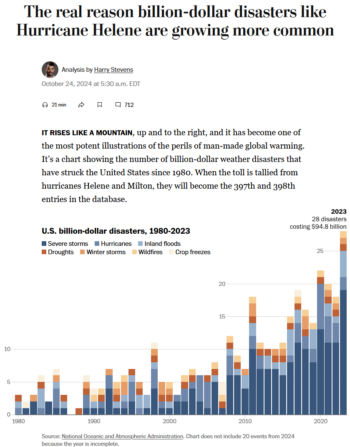

The drastic effects of climate change are causing havoc across the globe. In the southeastern U.S. and into Appalachia, hurricanes Helene and Milton have killed hundreds, left thousands without shelter and caused untold billions in damage. On the other side of the planet, parts of the Sahara desert flooded for the first time in nearly 50 years after intense rainstorms dropped 8 inches of rain in 2 days on parts of Morocco that don’t get more than an inch or so yearly. These storms and many other examples are showing that no one is safe from so-called storms of the century that seem to be happening weekly.

Meanwhile, insurance companies in Florida have been denying claims even from people who have been paying for hurricane-specific policies, and big landlords and investors are looking to profit from these disasters by buying up more land – all while doing nothing to address the climate crisis.

We’re joined today Ali by Abdel-Qader, a Palestinian organizer and Tampa-based activist who’s involved in relief efforts on the ground, and Tina Landis, author of Climate Solutions Beyond Capitalism.

https://covertactionmagazine.com/2024/1 ... the-world/

The Murder of Juan Lopez, Defender of Life

By James Phillips - October 16, 2024 0

Juan Lopez, (right)—seen here seated in front of a painting depicting Carlos Escaleras, an environmental activist in Tocoa, Honduras who was murdered in October of 1997. The nature reserve that contains the headwaters of the Guapinol River is named after him. [Source: Photo Courtesy of Lucy Edwards]

On the evening of September 14, Delegate of the Word Juan López had just finished leading a Saturday evening service at the Catholic church in Tocoa, Honduras.

Witnesses say that, as he was getting to his car, someone on a motorcycle rode by and shot him multiple times, killing him.

López was a teacher, community leader, and a member of the Tocoa municipal council. He was also a human rights activist and the most prominent environmental defender in Honduras since the assassination of water protector Berta Cáceres in 2016.

In 2015, the year before her assassination, Cáceres was awarded the international Goldman Environmental Prize for Indigenous environmental activism. In 2019 the Institute for Policy Studies awarded López, on behalf of the Guapinol Water Defenders, the Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Award for the defense of sovereignty, environment and human rights.

Berta Cáceres [Source: goldmanprize.org]

Juan López is already mourned throughout Honduras. There are demands not only to find and indict his killers—the one who shot him and those who ordered the killing—but also to condemn those who have institutionalized the systematic theft of the region’s environment and the displacement of its rural communities. That region is the Aguán Valley that has for long been a particularly violent area for land conflict and the destruction of peasant communities and cooperatives.

For many years, López had been fighting the devastation of mining and other uncontrolled environmental exploitation. He was part of a group of local people who have been waging decades-long resistance to the poisoning of the area’s rivers from mining. They are known in Honduras as the Guapinol Water Defenders for trying to protect their community and the Guapinol and San Pedro rivers.

Guapinol Water Defenders. [Source: uusc.org]

During the previous Honduran government—the U.S.-backed “narco-dictatorship” of Juan Orlando Hernández—the struggle to protect the environment in the area increased in urgency and danger when the mining company Los Pinares, owned by one of the wealthiest families in Honduras, began work on a large mining-hydropower complex.

Mining projects like this require enormous amounts of water, diverting it from local farmers and communities.

The result is that what little water remains is polluted, the surrounding area is difficult or impossible to farm, and communities are left with little or no potable water. The hydropower part of the Los Pinares mining plant meant the capture of more water, further threatening local communities and the environment.

The mining concession to Los Pinares was within the boundaries of the Carlos Escaleras National Park, a major environmental reserve that contains the headwaters of various rivers that provide water to local communities. People were concerned about their water supply and they were angered that the National Park was invaded by a mining project.

[Source: contracorriente.red]

The Guapinol Water Defenders, including Juan López and others, tried for years to get Los Pinares to enter into a consultation about this project, but met with little success. In frustration, they held a large public meeting to discuss and vote on the will of the local communities.

The vote was a resounding NO to the project. The government reacted by charging the Water Defenders with illegal association (i.e., conspiracy to commit crime), and detained and jailed dozens of people, including Juan López. Some were later released, but others were transferred to a high-security prison in another region where they remained for almost two years.

Los Pinares was initially a joint venture between the Honduran group EMCO and the giant U.S. steel company Nucor based in Charlotte, North Carolina. Nucor’s website boasts that the company is “North America’s most sustainable steel and steel products company.”

Nucor claims its direct investment in Los Pinares ended in 2019. The U.S. government over many years has failed to hold U.S.-based corporations to account, and has at least tacitly supported a climate of fear and intimidation in Honduras to ensure that U.S. corporations in Honduras and Honduran companies like Los Pinares continue to provide materials and wealth to the U.S.

[Source: qcnews.com]

The U.S. and powerful Honduran interests have issued warnings against trying to restrict or regulate foreign enterprise and extraction. This amounts to a prohibition against engaging in the kind of environmental and human rights activism exemplified by López and the Guapinol defenders. The U.S. ambassador and others have issued thinly veiled warnings to Honduran President Xiomara Castro’s government not to try to change this situation.

People came to Juan López for counsel and aid. His murder comes in the context of increasing pressures on the government of President Castro.

The United Nations and the Inter-American Committee on Human Rights had both mandated that the Honduran government provide protective measures (medidas cautelares) for López. Despite such protection, an assassin was able to kill him. The double message is clear to many Hondurans: Defenders of human rights and the environment will be eliminated and, despite all the protections, the killers and their bosses can kill anyone they want.

Xiomara Castro [Source: womensmediacenter.com]

The murder of López highlights the inability (weakness) of the Castro government in the face of the powerful corruption that still poisons much of the political economy and daily life of the country. When she was elected in 2021, Castro pledged to work to build a political economy that would de-emphasize dependence on foreign extraction and instead promote local enterprise and safeguard local communities.

Her government has taken some courageous actions—such as withdrawing from an international accord that allowed foreign corporations to sue Honduras for ending contracts with these corporations.

[Source: rowman.com]

The larger issue is the inability of governments to regulate the predations of international corporations on their soil, especially those based on the extraction or destruction of natural resources.

As I show in detail in my book, Extracting Honduras: Resource Exploitation, Displacement, and Forced Migration (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books 2022), such destruction is a root cause of emigration from countries like Honduras. But, despite all the hand wringing and vitriol about immigration police and border “security” in U.S. politics, U.S. and other foreign governments that should exercise regulation over the exploits of their corporations in countries like Honduras manifest a singular lack of will to do so.

The people of Honduras are victims of this aggressive and virtually uncontrolled exploitation. When their people try to defend their land and sovereignty, they are jailed or murdered with impunity.

The murder of Juan López is yet another stark reminder of the criminality of a global political economy that kills both people and the earth.

It is also a reminder that this criminal enterprise will always be strongly resisted by courageous defenders of life and environment.

But they could use the support of U.S. citizens working to hold U.S. politicians and corporations accountable for what they do in countries like Honduras.

https://covertactionmagazine.com/2024/1 ... r-of-life/

*****

How climate change destroyed a tar sands boomtown

October 16, 2024

Fire Weather: A remarkable account of the reality of disaster in modern neoliberal society

John Vaillant

FIRE WEATHER

On the Front Lines of a Burning World

Penguin Random House, 2023

reviewed by Martin Empson

I write this review in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Milton’s devastation of parts of Florida. Milton followed Helene, just a week or so earlier. Both hurricanes cut a swathe through parts of North America, leaving death and destruction in their paths.

John Vaillant’s recent book Fire Weather is subtitled a “true story from a hotter world” and the story of hurricanes Milton and Helene could have shared that subtitle. They were both made worse by the hotter world we now live on. Scientists and environmentalists have longed warned about the feedback mechanisms of a warmer planet. As the world gets warmer, climate change further encourages the warming of the world. This cycle accelerates the speed of warming. The catastrophes that accompany a hotter planet come thicker and faster.

Fire Weather deals with just one such catastrophe, but it is an emblematic and enlightening one, the destruction of Fort McMurray in Alberta, Canada in 2016. There’s a grim feedback mechanism in play here, for McMurray is at the heart of fossil fuel capitalism. It was for many years a boomtown driven by the wealth of the region’s tar sands. The bitumen deposits here are difficult to turn into profitable commodities. But when the price of oil is high enough there are bonanzas to be made. McMurray was a town built on bonanza.

Vaillant traces the history of McMurray, and indeed, the history of industrial capitalism’s obsession with oil. Its a fascinating story that shows the way that capitalism embedded nature, and its resources, into a global commodity system. McMurray started off as an isolated place where animal skins and fur were trapped and sold, before morphing into an (isolated) 21st century oil city. Weaved in with this history is a longer story of humanity’s relationship with fire. Combustion, burning, fire are essential for humans. We need fire for travel, heating and food. But fire is also intrinsic to nature. The boreal forests that surround McMurray for tens of thousands of square miles need fire to renew and propagate. Humans think of such fires as a threat that needs to be fought — an invading army that has to be countered with traps, weapons and occasional retreat (the retreats are more common now). But the fires that engulf Alberta are part of that ecological system, its just that (unfortunately for humanity) they are more frequent, more intense and more common in a warming world.

Vaillant explains fire to us. But his use of metaphor is interesting. Describing how wildfires crossover (“when the ambient temperature in degrees Celsius exceeds the relative humidity as a percentage”) and become an exponentially faster, more agile, more dangerous fire, Vaillant says that “if unregulated free market capitalisms were a chemical reaction, it would be a wildfire in crossover conditions.” He continues “Alberta’s bitumen industry follows a similar growth pattern, with market forces standing in for weather.”

Capitalism is the problem here. It drives an endless accumulation of wealth for the sake of accumulation, based on an insatiable burning of natural resources. It is a wildfire of production, and as it grows it sucks in more nature, more humanity and expels material that pollutes and destroys. The irony of McMurray is that it was destroyed by its own forces of production, or rather the consequences of the usage of the use-values it produced. In fact Vaillant’s book is really about the intersection of urban fossil fuel capitalism and wildfire. As he writes:

“Combustive energy had drawn people to Fort McMurray in steadily increasing numbers over the course of a century, and combustive energy was driving them out again, en masse, in a single afternoon… the exodus of May 3 [2016] was the largest, most rapid displacement of people due to fire in North American history. It took the form of an unbroken ribbon of vehicles crawling in ranks, like army ants, northward and southward out of the city while fire raged along the highway, in some cases right up to the breakdown lanes.”

Hurricane Milton in mind, as well as Vaillant’s accounts of the escape from McMurray, it might be that the defining images of 21st century global warming in the Global North will be endless streams of SUVs and trucks driving away from environmental disasters. Climate refugees from the global south are met with barbed wires and closed borders. In the global north the Ford F-150s were given a much friendlier welcome. In one way the Fort McMurray fire was a very unusual climate disaster. Unusual circumstances combined with a rare urban environment.

“Hundredth-percentile fire weather conditions during the hottest, driest May in recorded history, following a two-year drought in a sudden city filled with twenty-five thousands petroleum-infused boxes and surrounded by millions of desiccated trees.

But as Vaillant points out, “this is the nature of twenty-first-century WUI [Wildland Urban Interface] fire.” Once in a lifetime events are becoming once in a decade events. Soon they’ll be more common.

If Vaillant had only written the story of McMurray and the urban-wildfire environment it would have been a fine book. But at the heart of the story is that of McMurray’s population. His account of the desperate evacuation, the struggle of the authorities to adjust to rapidly changing and unprecedented fire condition and the battle of the firefighters itself is a remarkable account of the reality of disaster in modern neoliberal society.

It is the story of a city that is really unable to deal with the disaster, not because of incompetence, or lack of training, or even lack of resources (something that most people in the world facing disaster will not have), but because there was no real understanding that a disaster on this scale could even happen. In many ways McMurray was better prepared than most cities for fire, because it could draw on the resources and fire-fighting experience provided by the oil industry itself. But the failure to control the fire happened because it was on a scale far beyond imagination. In fact clear is that traditional fire fighting doesn’t work in the in the 21st century WUI, and new methods of fire control need to be learnt. Interestingly it seems that allowing firefighters and workers to make decisions based on events and knowledge, rather than centralized leadership, is one lesson to be learnt from these massive fires.

Reading Vaillant’s account of the breakdown of control I was reminded of those highly popular 1970s brick sized novels epitomized by Arthur Hailey. In those wonderful disaster stories, tiny mistakes and failures would accumulate into a giant failure. In McMurray there were plenty of such failures that combined to help the fire reach epidemic proportions, but there was no lack of bravery. In fact the stories of the firefighters and indeed ordinary workers who fought day after day to save their city are inspiring. One wonders what is left for them. Vaillant quotes one Radio director who said afterward, “imagine a city — thousands of people — all living in everyday harmony, each and every one with some aspect of PTSD.”

There’s going to be more. Vaillant writes that “hotter and drier now, the atmosphere has been tilted in fire’s favor.” As the hammer of global warming drives more and more hurricanes, wildfires, heat waves and floods against the anvil of capitalism’s fractured and divided society, there will be endless death and destruction. There will also be plenty of PTSD for the survivors. But the bravery, industry and inventiveness of the workers who fought the fire in McMurray, and who rebuilt the town, are the potential force for change. John Vaillant concludes his superb book, by arguing for a different vision to that offered by fossil fuel capitalism — “devoting our energy and creativity to regeneration and renewal, rather than combustion and consumption.” Let’s hope that these lessons are learned, from Fort McMurray and hurricanes Helene and Milton.

https://climateandcapitalism.com/2024/1 ... rich-city/