Ideology

Re: Ideology

Pied Pipers of the "Left", Leading Those Seeking Change Into a Dead End: Perry Anderson.

A Very Western Marxist Serving the Capitalist Oligarchy

Roger Boyd

Sep 13, 2025

Perry Anderson is Professor of History at UCLA, Los Angeles (a position that he has held for two and a half decades) and very much represents the “Western Trotskyist” academic grouping, while being instrumental in the success of the New Left Review; where he was the editor for two decades from 1962.

Coming from an upper middle-class / lower upper class family, he went to school at Eton and then studied for his BA in French and Russian Literature & Language at Worcester College, Oxford from 1956 to 1959. His position as the editor of New Left Review established him among the major left British thinkers in the decades of the 1960s and 1970s. He then moved into academia as the Professor of Politics & History at the New School, New York University from 1985 to 1987, and then into his current position at UCLA. He has held numerous fellowships and visiting professorships across mostly Europe and the US, together with a stint at the World Bank as a consultant from 1986 to 1988. To say that he has absolutely no personal knowledge of being working class, or even middle class, is to state the obvious and at no time did he engage in any activism that may have connected him with the working class. A class that he has no real knowledge of, but ironically one that he sees as the central subject that would lead a socialist transformation. He has also spent little time working with intellectuals and activists outside the West.

He was a brilliant scholar, but one theorizing within the confines of an intellectual periodical and the halls of academia about things that he had no direct knowledge of, or participation in. As with many of the leading post-WW2 Western Marxist scholars he stands out from the likes of Gramsci, who combined a very direct knowledge of economic want and extensive social and political activism with his theorizing; practice and praxis. As was the case with the communist revolutionaries in the Soviet Union, China, Cuba and many Latin American and African nations. As George Souvlis states in this article:

At the same time, Anderson never became an activist. Rather, he was a politically and theoretically informed intellectual, akin to those of the Eurocommunist parties that he condemned in Considerations on Western Marxism. This particularity was also reflected in his method, which lacked any explicit reductionism — of ideas or politics — to the economic level.

He remained within an analytical framework that privileged the geopolitical conflict between the October Revolution and its enemies as determinant factors of emerging ideas. This epistemological suggestion is not very different from the Weberian tradition, where the Political functions as an autonomous sphere in relation to the economy.

A historical-materialist approach on the level of ideas would, instead, be closer to that presented in works on the history of political thought by Ellen Meiksins Wood. Her approach to political ideas is, instead, defined by a set of regulating concepts such as social relations, property forms, and state formation.

Like the Western Marxists, Anderson also cherry-picked Gramsci when he formulated his work. Another such example is Souvlis, a Western Marxist that misrepresents and cherry-picks Gramsci himself to laughably declare Gramsci as being within his own camp. Souvlis though does capture the taming of Marxism, especially in the Anglo-Saxon world, into an intellectual discipline kept within a gilded academic careerist cage constructing self-referential works and arguing over theoretical differences that hold no challenge to the capitalist oligarchy.

In the 1980s, Marxism was challenged by other theoretical paradigms from within academic fields that had progressive political connotations — not by a social movement that could reshape and redirect its priorities.

This is why Anderson’s narration notes the antagonism between different theoretical traditions within university structures, not outside of them. British and American universities could continue to “host” the Marxist tradition since here the Left never posed a substantial challenge to their status quo.

The establishment did not erase Marxism completely, but integrated it as another theoretical tradition separated from political practice. Adopting this line of reasoning, one could argue that Anderson’s trilogy on Marxism was itself a product of this defeat. Its impasses, therefore, should be interpreted according to these seismic shifts in the world-system, rather than as failures of specific theoretical paradigms in the Marxist canon or the author himself.

It is notable that Anderson spent his last two decades in academia in California, utterly disconnected from struggles outside the West and even outside the front door of the academy. As he sunk into the gilded careerist cage of academia:

Debates within the Marxist canon on issues of theory and strategy were substituted by intra-academic discussions concerning the proper method in the discipline of intellectual theory. His self-understanding as a Marxist attempting to challenge the fallacies of political reformism and non-dialectical theory was thus replaced by the adoption of methods from within university milieus.

Unlike Gramsci, Anderson did not use an explicitly Marxist analytical framework in his historical analyses of political thought in contrast to the Amsterdam School that fully embraced Gramsci’s historical materialism. Anderson recently wrote a piece for the London Review of Books, a place where tamed Marxist thought can be published, which quite well details the surface elements of the ongoing capitalist crisis but in no way delves into the realities of capitalist oligarchic dominance. Falling into the false dichotomy between the Democrats and Republicans, rather than seeing both as instruments of the oligarchy and representing differences of opinion and changes in the methods deemed applicable within the oligarchy; from the manufactured consent of performative bourgeois democracy to greater authoritarianism and even outright fascism.

Anderson notes the upsurge of left-wing activism and parties in the mid-2010s (e.g. Syriza, Podemos, Corbyn in the British Labour Party, Saunders in the Democratic Party), but then seems to suffer complete memory loss for the following years of the utter defeat and/or oligarch co-option of those left wing movements; apart from a quick note about the treachery of Syriza. He also utterly misses the German capitalist ruling class role in nurturing the AfD as their own tool of deepening neoliberalism. He does note the ideological knots tying up many on the left when it comes to dealing with working people’s concerns about mass immigration, but this is surface tactics not deep insight. He falls into considering neoliberalism and populism as being opposites when they are in fact different oligarch strategies of social control, with the right-wing populist AfD being neoliberal to its core. As is the Trump administration with its implementation of Project 2025, as are Starmer and Farage, as is the French National Rally and as is Meloni of Italy.

It is notable that his examples of social revolutions without the need for overarching ideological underpinnings are the Brazilian bourgeois “revolution” of Vargas in the Brazil of 1930 and the opening up of China lead by Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s after the end of the Cultural Revolution. The former was actually a member of the oligarchy that came to power through a bourgeois armed revolution, ruled as a dictator for most of his period in power, and brutally put down a number of popular attempts at proletarian revolutions. The success of Deng’s policies rested upon the ideological, social and economic strengthening of China under Mao. Like many Trotskyists, Anderson greatly exaggerates the “chaos” of the Cultural Revolution while ignoring the positive effects for the vast majority of the population that lived outside the major cities. He ends up sounding very much like a progressive social democratic reformer rather than a Marxist, this for a man celebrated as one of the greatest Marxist thinkers of the post-WW2 world. In this he falls very much within the category of post-WW2 ivory-tower captured leftists that Losurdo and Rockhill so well identify.

In the introduction to the English translation of Losurdo’s Western Marxism, Jennifer Ponce De Leon and Gabriel Rockhill note that the book is an explicit rejoinder to Anderson’s Considerations of Western Marxism and that Anderson’s work exhibits much of the “patronizing Eurocentrism, idealism, and complicity with imperialism” that is redolent within the very Western Marxism that he is criticizing. They also note Anderson’s bizarre classification of Gramsci (and Lukacs) as Western Marxists. Also, Anderson’s complete mischaracterizations of Stalinism, which would of course be expected from a Trotskyist.

As Losurdo notes, Anderson laughably stated in the postscript to his book that socialism did not exist anywhere in the world; utterly ignoring the real existing socialism of Cuba, China, the Soviet Union and even Burkina Faso under Thomas Sankara. Displaying the “never perfect enough” Trotskyist ideological dead end, and the superiority complex of Western ivory-tower Marxists. Fundamentally, Western Marxism tends to be a fanciful ideology that calls for the destruction of the state in very much the same way that neoliberalism does, while Eastern Marxism understands the core role of the state as a tool of class struggle against capitalist and other ruling class oligarchies. In this way, Western Marxism acts as an impediment to real change; exactly why its fully house-trained and domesticated academics can be tolerated by the bourgeois academy. Pied pipers leading those that want change on a self-defeating theoretical journey that redirects and saps their revolutionary energy, while achieving comfortable upper middle class lives for themselves.

https://rogerboyd.substack.com/p/pied-p ... ding-those

A Very Western Marxist Serving the Capitalist Oligarchy

Roger Boyd

Sep 13, 2025

Perry Anderson is Professor of History at UCLA, Los Angeles (a position that he has held for two and a half decades) and very much represents the “Western Trotskyist” academic grouping, while being instrumental in the success of the New Left Review; where he was the editor for two decades from 1962.

Coming from an upper middle-class / lower upper class family, he went to school at Eton and then studied for his BA in French and Russian Literature & Language at Worcester College, Oxford from 1956 to 1959. His position as the editor of New Left Review established him among the major left British thinkers in the decades of the 1960s and 1970s. He then moved into academia as the Professor of Politics & History at the New School, New York University from 1985 to 1987, and then into his current position at UCLA. He has held numerous fellowships and visiting professorships across mostly Europe and the US, together with a stint at the World Bank as a consultant from 1986 to 1988. To say that he has absolutely no personal knowledge of being working class, or even middle class, is to state the obvious and at no time did he engage in any activism that may have connected him with the working class. A class that he has no real knowledge of, but ironically one that he sees as the central subject that would lead a socialist transformation. He has also spent little time working with intellectuals and activists outside the West.

He was a brilliant scholar, but one theorizing within the confines of an intellectual periodical and the halls of academia about things that he had no direct knowledge of, or participation in. As with many of the leading post-WW2 Western Marxist scholars he stands out from the likes of Gramsci, who combined a very direct knowledge of economic want and extensive social and political activism with his theorizing; practice and praxis. As was the case with the communist revolutionaries in the Soviet Union, China, Cuba and many Latin American and African nations. As George Souvlis states in this article:

At the same time, Anderson never became an activist. Rather, he was a politically and theoretically informed intellectual, akin to those of the Eurocommunist parties that he condemned in Considerations on Western Marxism. This particularity was also reflected in his method, which lacked any explicit reductionism — of ideas or politics — to the economic level.

He remained within an analytical framework that privileged the geopolitical conflict between the October Revolution and its enemies as determinant factors of emerging ideas. This epistemological suggestion is not very different from the Weberian tradition, where the Political functions as an autonomous sphere in relation to the economy.

A historical-materialist approach on the level of ideas would, instead, be closer to that presented in works on the history of political thought by Ellen Meiksins Wood. Her approach to political ideas is, instead, defined by a set of regulating concepts such as social relations, property forms, and state formation.

Like the Western Marxists, Anderson also cherry-picked Gramsci when he formulated his work. Another such example is Souvlis, a Western Marxist that misrepresents and cherry-picks Gramsci himself to laughably declare Gramsci as being within his own camp. Souvlis though does capture the taming of Marxism, especially in the Anglo-Saxon world, into an intellectual discipline kept within a gilded academic careerist cage constructing self-referential works and arguing over theoretical differences that hold no challenge to the capitalist oligarchy.

In the 1980s, Marxism was challenged by other theoretical paradigms from within academic fields that had progressive political connotations — not by a social movement that could reshape and redirect its priorities.

This is why Anderson’s narration notes the antagonism between different theoretical traditions within university structures, not outside of them. British and American universities could continue to “host” the Marxist tradition since here the Left never posed a substantial challenge to their status quo.

The establishment did not erase Marxism completely, but integrated it as another theoretical tradition separated from political practice. Adopting this line of reasoning, one could argue that Anderson’s trilogy on Marxism was itself a product of this defeat. Its impasses, therefore, should be interpreted according to these seismic shifts in the world-system, rather than as failures of specific theoretical paradigms in the Marxist canon or the author himself.

It is notable that Anderson spent his last two decades in academia in California, utterly disconnected from struggles outside the West and even outside the front door of the academy. As he sunk into the gilded careerist cage of academia:

Debates within the Marxist canon on issues of theory and strategy were substituted by intra-academic discussions concerning the proper method in the discipline of intellectual theory. His self-understanding as a Marxist attempting to challenge the fallacies of political reformism and non-dialectical theory was thus replaced by the adoption of methods from within university milieus.

Unlike Gramsci, Anderson did not use an explicitly Marxist analytical framework in his historical analyses of political thought in contrast to the Amsterdam School that fully embraced Gramsci’s historical materialism. Anderson recently wrote a piece for the London Review of Books, a place where tamed Marxist thought can be published, which quite well details the surface elements of the ongoing capitalist crisis but in no way delves into the realities of capitalist oligarchic dominance. Falling into the false dichotomy between the Democrats and Republicans, rather than seeing both as instruments of the oligarchy and representing differences of opinion and changes in the methods deemed applicable within the oligarchy; from the manufactured consent of performative bourgeois democracy to greater authoritarianism and even outright fascism.

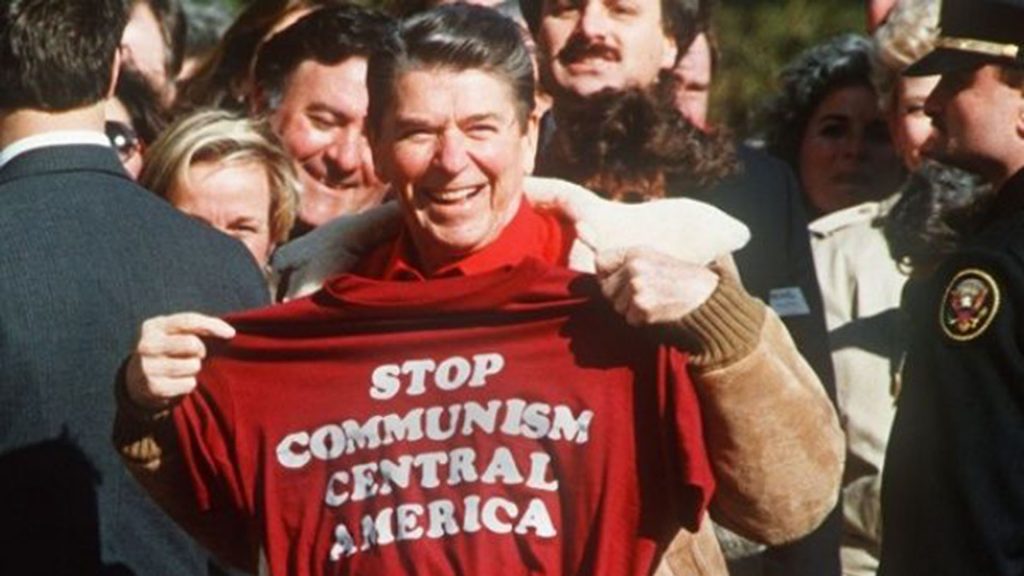

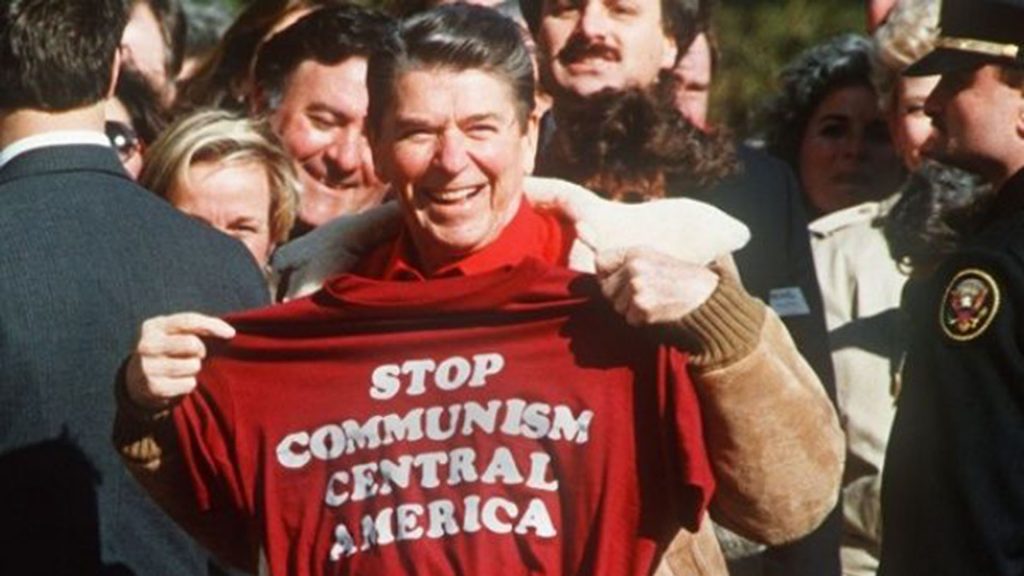

Anderson notes the upsurge of left-wing activism and parties in the mid-2010s (e.g. Syriza, Podemos, Corbyn in the British Labour Party, Saunders in the Democratic Party), but then seems to suffer complete memory loss for the following years of the utter defeat and/or oligarch co-option of those left wing movements; apart from a quick note about the treachery of Syriza. He also utterly misses the German capitalist ruling class role in nurturing the AfD as their own tool of deepening neoliberalism. He does note the ideological knots tying up many on the left when it comes to dealing with working people’s concerns about mass immigration, but this is surface tactics not deep insight. He falls into considering neoliberalism and populism as being opposites when they are in fact different oligarch strategies of social control, with the right-wing populist AfD being neoliberal to its core. As is the Trump administration with its implementation of Project 2025, as are Starmer and Farage, as is the French National Rally and as is Meloni of Italy.

It is notable that his examples of social revolutions without the need for overarching ideological underpinnings are the Brazilian bourgeois “revolution” of Vargas in the Brazil of 1930 and the opening up of China lead by Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s after the end of the Cultural Revolution. The former was actually a member of the oligarchy that came to power through a bourgeois armed revolution, ruled as a dictator for most of his period in power, and brutally put down a number of popular attempts at proletarian revolutions. The success of Deng’s policies rested upon the ideological, social and economic strengthening of China under Mao. Like many Trotskyists, Anderson greatly exaggerates the “chaos” of the Cultural Revolution while ignoring the positive effects for the vast majority of the population that lived outside the major cities. He ends up sounding very much like a progressive social democratic reformer rather than a Marxist, this for a man celebrated as one of the greatest Marxist thinkers of the post-WW2 world. In this he falls very much within the category of post-WW2 ivory-tower captured leftists that Losurdo and Rockhill so well identify.

In the introduction to the English translation of Losurdo’s Western Marxism, Jennifer Ponce De Leon and Gabriel Rockhill note that the book is an explicit rejoinder to Anderson’s Considerations of Western Marxism and that Anderson’s work exhibits much of the “patronizing Eurocentrism, idealism, and complicity with imperialism” that is redolent within the very Western Marxism that he is criticizing. They also note Anderson’s bizarre classification of Gramsci (and Lukacs) as Western Marxists. Also, Anderson’s complete mischaracterizations of Stalinism, which would of course be expected from a Trotskyist.

As Losurdo notes, Anderson laughably stated in the postscript to his book that socialism did not exist anywhere in the world; utterly ignoring the real existing socialism of Cuba, China, the Soviet Union and even Burkina Faso under Thomas Sankara. Displaying the “never perfect enough” Trotskyist ideological dead end, and the superiority complex of Western ivory-tower Marxists. Fundamentally, Western Marxism tends to be a fanciful ideology that calls for the destruction of the state in very much the same way that neoliberalism does, while Eastern Marxism understands the core role of the state as a tool of class struggle against capitalist and other ruling class oligarchies. In this way, Western Marxism acts as an impediment to real change; exactly why its fully house-trained and domesticated academics can be tolerated by the bourgeois academy. Pied pipers leading those that want change on a self-defeating theoretical journey that redirects and saps their revolutionary energy, while achieving comfortable upper middle class lives for themselves.

https://rogerboyd.substack.com/p/pied-p ... ding-those

"There is great chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent."

Re: Ideology

Imperialism, Multipolarity, and Palestine

It is a continuing source of frustration that an important segment of the left holds the view that weakening the United States’ long-established grip on the top rungs of the hierarchical system of imperialism is-- in itself-- an attack on imperialism.

Many of our friends, including those who claim to aim at a socialist future, mistakenly see an erosion in the US position as the imperialist system’s hegemon as necessarily a step guaranteeing a just future, lasting peace, or a step towards socialism.

While it is true that those fighting the most powerful nation-state in the imperialist system for sovereignty, for autonomy, for a path of their own choosing always deserve our enthusiastic and complete support, victory in that fight may or may not secure a better future for working people. They may, as happened so often in the anti-colonial struggles of the post-war period, find themselves cursed with a power-hungry, exploitative, undemocratic local ruling class continuing or expanding the oppression of the people, but maybe with a more familiar face.

Or they might suffer the replacement of a former, declining or defeated great power by another more powerful great power. Germany and Turkey, defeated in World War I, lost many of their colonies to the victors; after World War II, some of Japan’s colonies were recolonized, falling into the clutches of another superior power; and, of course, Vietnam defeated France, only to be oppressed into the US sphere of interest-- a result decisively overturned by heroic Vietnam.

To contend that the decline or fall of the US as the leading great power in the imperialist system could close the book on imperialism is to grossly misunderstand imperialism. Imperialism lingers as a stage of capitalism as long as monopoly capitalism exists.The ultimate battle against imperialism is the struggle against capitalism.

We must not confuse the participants in the global imperialist system with the system itself, any more than we should equate individual capitalist corporations with the capitalist system itself.

History offers no example of a global or semi-global power falling or removed from the heights of its domination leading to a period of world-wide peace and prosperity. Neither the fall of the Roman or the Eastern Roman Empire or the Holy Roman Empire ushered in such a period of harmony. Nor did the rise and fall of the Venetian Republic, the Dutch Republic, or the Portuguese or Spanish colonial empires of the mercantilist era. In Lenin’s time, the rivalries challenging Britain’s global dominance brought world war rather than peace. And its aftermath brought no harmony. Instead, capitalist rivalries with Germany and Japan generated even more devastating aggression and war. And with the dissolution of the once dominant British Empire after the war, the US assumed and brutally enforced its position at the top of the hierarchy of global powers.There is no reason to believe that matters will change with the US knocked off its reigning perch. Capitalism and its tendency toward war and misery persist.

Thus, history provides no evidence for the supplanting of a unipolar world with a sustainable multipolar capitalist world of mutual respect and harmony. Multipolarity alone, as a solution to the oppression of imperialism, is, in fact, never found in world history.

Of course it may be factually true that United States dominance of the world imperialist system may be on the wane. Certainly, the decisive defeat in Vietnam was an enormous setback to the US government’s ability to dictate to weaker states. Further the defeat in Afghanistan after a twenty year war shows a weakening. The defiance of the DPRK and Cuba’s resilience also show limitations to US imperialism today.

Further, the rise of Peoples’ China as an economic powerhouse and as a sophisticated military power is perceived by the US government as both an economic and military adversary, though there is no reason to believe that the PRC presents any greater threat to the imperialist system than does the Papal State. Both today express well-deserved outrage at the worst excesses of imperialism, but make little material contribution to its overthrow.

Marginalizing, weakening, or defanging the arch-imperialist power is to be welcomed, though the left should suffer no illusion that the action would be an end to imperialism, a decisive blow against the capitalist system, or of long-lasting benefit of working people.

A recent example of the multipolarity fallacy-- the romantic illusion that imperialism is only US imperialism-- is the many leftist reports on the early September meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) attended by President Xi, President Putin, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and other Eurasian leaders. Professor Michael Hudson enthused that:

The principles announced by China’s President Xi, Russian President Putin and other SCO members set the stage for spelling out in detail the principle of a new international economic order along the lines that were promised 80 years ago at the end of World War II but have been twisted beyond all recognition into what Asian and other Global Majority countries hope will have been just a long detour in history away from the basic rules of civilization and its international diplomacy, trade and finance.

Hudson foresees a new economic order fulfilling a promise made eighty years ago. But he doesn’t tell us how a new capitalist international order will be different from the earlier capitalist international order, apart from the idealistic words of its advocates. He doesn’t explain how the inter-imperialist rivalries associated with capitalist great powers are to be avoided. He fails to show how the competitive, cut-throat nature of capitalist social-relations can be somehow tamed. He builds his case around high-minded words uttered at a conference, as if those or similar words were not uttered eighty years ago at the Bretton Woods conference.

Much has been made of the warm announcement by Xi and Modi that they are “partners not rivals”. But as the insightful Yves Smith relays:

A new Indian Punchline article, India disavows ‘Tianjin spirit’, turns to EU, reviews the idea that India is jumping with both feet into the SCO-BRICS camp is overdone. Key section from that post:

….no sooner than Modi returned to Delhi, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar had lined up the most hawkish anti-Russia gang of European politicians to consort with in an ostentatious display of distancing from the Russia-India-China troika.

To underscore the skepticism of the Indian Punchline article, Modi chose not to attend the virtual BRICS trade summit subsequently called by Brazilian President Lula da Silva.

In his place, minister Jaishankar chose the occasion to raise the issue of trade deficits with BRICS members, noting that they are responsible for India’s largest deficits and that India is expecting to secure a correction-- hardly a gesture of mutual confidence in India's BRICS brothers and sisters. It is more an example of geo-political bargaining.

Nor does Peoples’ China embrace the romantic idealism of our leftist friends”, as the following quote asserts:

“China is very cautious about working with these two countries [Russia and PDRK]. Unlike what is depicted in the West as them being allies, China is not in the same camp. Its view of warfare and security issues is very different from theirs,” said Tang Xiaoyang, chair of the department of international relations at Tsinghua University, pointing out that Beijing hasn’t fought a war for more than four decades. “What China wants is stability on its borders.”

One might conclude that the left’s hope in a BRICS led new, more just international order is little more than a chimera. BRICS appears to be, at best, an opportunistic economic alliance, with neither the political or military weight to press multipolarity on a unipolar world.

*****

There is. as well, a theoretical argument for a left investment in the idea of multipolarity as an answer to imperialism. It is an old argument. It was crafted by Karl Kautsky and advanced in an article entitled Ultra-imperialism and published in Die Neue Zeit in September, 1914, just a month after the beginning of World War I.

In short (I deal with the arguments more fully here, here, and here), Kautsky argued that the great powers would divide the world up among themselves and resolve to avoid further competition and rivalry. They would recognize the irrationality and counterproductiveness of aggression and war, opting for a harmonious imperialism that Kautsky called “ultra-imperialism”. He maintained that:

The frantic competition of giant firms, giant banks and multi-millionaires obliged the great financial groups, who were absorbing the small ones, to think up the notion of the cartel. In the same way, the result of the World War between the great imperialist powers may be a federation of the strongest, who renounce their arms race.

Similarly, today’s multipolaristas/ultra-imperialists envision a world in which a covey of powerful countries will expel the US from its leadership of the global capitalist system for its bad behavior, with its EU satrapy falling in line. In its place, they will create a new “harmonious”, “win-win” order that will eliminate the inequalities between the “global north” and the “global south”. The en-actors and enforcers of this new order will be a motley crew of class-divided, capitalist-oriented states led by an equally motley crew, including despots, theocrats, and populists. All but one of the BRICS+ espouse anything other than a firm allegiance to capitalism; most are hostile to any alternative social system like socialism.

Lenin, in a 1915 introduction to Bukharin’s Imperialism and World Revolution, mocked Kautsky’s argument and ideas like ultra-imperialism:

Reasoning theoretically and in the abstract, one may arrive at the conclusion reached by Kautsky… his open break with Marxism has led him, not to reject or forget politics, nor to skim over the numerous and varied political conflicts, convulsions and transformations that particularly characterise the imperialist epoch; nor to become an apologist of imperialism; but to dream about a "peaceful capitalism." "Peaceful" capitalism has been replaced by unpeaceful, militant, catastrophic imperialism… In this tendency to evade the imperialism that is here and to pass in dreams to an epoch of "ultra-imperialism," of which we do not even know whether it is realisable, there is not a grain of Marxism… For to-morrow we have Marxism on credit, Marxism as a promise, Marxism deferred. For to-day we have a petty-bourgeois opportunist theory -- and not only a theory -- of softening contradictions (quoted in my article cited above)

The key relevant thoughts here are “peaceful capitalism”, “Marxism on credit”, and “softening contradictions”. Lenin is shocked at Kautsky-- a self-styled Marxist-- even entertaining the notion of a peaceful capitalism, an idea that violates the very logic of capitalist social relations; it should be a wake-up call to multipolaristas.

“Marxism on credit” is a mockery of the notion that counting on some hoped for agreement between capitalist great powers to tame imperialism is as foolish as running your credit card to its limit. For multipolaristas, it is pushing the day of reckoning with capitalism off into the far, far distant future.

Likewise, Kautsky “softens” the contradiction between rival capitalist states by imagining an impossible agreement to guarantee “harmonious” relations, a proposition Lenin completely rejects. Concisely, Lenin sees Kautsky’s opportunism as a retreat from the socialist project. The same can be said for the multipolarity project.

Far too many on the left refuse to look at multipolarity through this lens of Lenin’s theory of imperialism, especially as expressed with considerable clarity in his 1916 pamphlet, Imperialism.

Regarding the promise of multipolarity, Lenin here offers a hypothetical scenario where imperialist powers do manage to cut up the world and arrive at an alliance dedicated to peace and mutual prosperity. Would that idealized multipolar system-- what Kautsky calls “ultra-imperialism”-- succeed in eliminating “friction, conflicts and struggle in all and every possible form”?

The question need only be stated clearly enough to make it impossible for any other reply to be given than that in the negative… Therefore in the realities of the capitalist system, and not in the banal philistine fantasies of English parsons [Hobson], or of the German “Marxist,” Kautsky, “inter-imperialist” or “ultra-imperialist” alliances, no matter what form they may assume, whether of one imperialist coalition against another, or of a general alliance embracing all the imperialist powers, are inevitably nothing more than a “truce” in periods between wars. Peaceful alliances prepare the ground for wars, and in their turn grow out of wars; the one is a condition for the other, giving rise to alternating forms of peaceful and non-peaceful struggle out of one and the same basis of imperialist connections and the relations between world economics and world politics. [Lenin’s emphasis]

Thus, while capitalism persists, Lenin makes the case for unabated intra-class struggle on the international level, struggles that manifest as inter-imperialist rivalry and war.

Of course it is possible to reject Lenin’s argument, even Lenin’s theory of imperialism. It is also possible to praise Lenin’s views as relevant for its time, but inapplicable today, in light of the many changes in global capitalism. That would be to say that the system of imperialism that Lenin set out to analyze no longer exists, replaced by a different system.

There is a precedent for correcting Lenin’s theory. Kwame Nkrumah, writing in 1965, showed that imperialism had largely abandoned the colonial project in favor of a more rational, efficient, but still brutally exploitative form of imperialism: neo-colonialism. His book, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism makes that case persuasively.

One cannot assume that Lenin’s is the final word on today’s imperialism.

And that is the tactic that Carlos Garrido takes in his recent essay, Why Russia and China are NOT Imperialist: A Marxist-Leninist Assessment of Imperialism’s Development Since 1917. Garrido ambitiously explores many subjects in this brief essay, including the errors of “Dogmatic Marxist-Leninists”, the place-- if any-- of Russia and the PRC in the imperialist system, Marxist methodology, the contemporary status of finance capital, Michael Hudson’s notion of super imperialism, the significance of Bretton Woods and the abandonment of the gold standard, as well as the relevance of Lenin’s theory of imperialism to today’s global economy.

Addressing all of these issues would take us far away from the current discussion, though they deserve further study.

To the point, he writes:

It appears to me that the imperialist stage Lenin correctly assessed in 1917 undergoes a partially qualitative development in the post-war years with the development of the Bretton Woods system. This does not make Lenin “wrong,” it simply means that his object of study – which he correctly assessed at his time of writing – has undertaken developments which force any person committed to the same Marxist worldview to correspondingly refine their understanding of imperialism. Bretton Woods transforms imperialism from an international to a global phenomenon, embodied no longer through imperialist great powers, but through global financial institutions (the IMF and the World Bank) controlled by the U.S. and structured with dollar hegemony at its core.

He adds that with Nixon’s move from the gold-standard, “imperialism becomes synonymous with U.S. unipolarity and hegemonism.”

This is wrong. As Garrido affirms, “Imperialism [in Lenin’s time] was not simply a political policy (as the Kautskyites held), but an integral development of the capitalist mode of life itself.” [my emphasis]

Likewise imperialism today is not a set of political policies, but an essential expression of contemporary capitalism.

Yet Garrido follows Kautsky in confusing today’s imperialism with a set of political policies: Bretton Woods and the US withdrawal from the gold- standard. The entire post-war trade and financial infrastructure was the result of policy decisions. They were shaped not by a “new” imperialism, but by the overwhelming economic power of the US after the war. As Garrido knows, that asymmetry is being challenged today, but it is a challenge to the policies or the power enjoyed by the US and not to the imperialist system.

The “transformation” that Garrido believes he sees is simply a reordering of the international system that existed before the war with New York now replacing London as the financial center of the capitalist universe. It is the replacement of the vast colonial world and the bloody rivalries and shifting alliances and hierarchies of the interwar world with the creation of a neo-colonial system dominated by the US and reinforced by its assumption of the role of guardian of capitalism in the Cold War. The monopoly capitalist base is qualitatively the same, but its superstructure changes with historical circumstances. The Bretton Woods system and the later discarding of the gold standard reflect those changing circumstances.

How does Garrido’s “new” imperialism function?

What matters is that capitalism has developed into a higher stage, that the imperialism Lenin wrote of is no longer the “latest” stage of capitalism, that it has given way – through its immanent dialectical development – to a new form marked by a deepening of its characteristic foundation in finance capital. We are finally in the era of capitalist-imperialism Marx predicted in Volume Three of Capital, where the dominant logic of accumulation has fully transformed from M-C-M’ to M-M’, that is, from productive capital to interest-bearing, parasitic finance capital.

Garrido’s reference to volume III of Capital would seem to be at odds with mine and others’ reading of that volume. In chapter 51, the last complete chapter, Marx, via Engels, brings matters back to the beginning, to commodity production. He dispels the view that there is any independent source of value in distribution-- in circulation, rent or “profit”. It is wage labor in commodity production that produces value in the capitalist mode of production. That is why Marx notes in Volume III that “The real science of modern economy only begins when the theoretical analysis passes from the process of circulation to the process of production.” (Vol. III, International Publishers, p.337).

Of course Marx acknowledges stock markets and would not be shocked by the financial sector's suite of exotic instruments like derivatives and swaps. Marx explains them under the rubric: "fictitious capital”. By “fictitious” Marx means forward-looking-- promissory notes against future value or “bets”. They circulate among capitalists and are acquired as contingent value. They become attractive in times of overaccumulation-- the super-concentration of capital in few hands-- when investment opportunities in the productive economy grow slim. And they disappear miraculously when the future that they depend upon does not materialize.

Garrido’s misunderstanding of the international role of finance capital leads him to make the claim that “...the lion's share of profits made by the imperialist system are accumulated through debt and interest.” At its peak before the great crash of 2007-2009, finance (broadly speaking, finance, insurance, real estate) accounted for maybe forty percent of US profits; today, with the NASDAQ techs, the percentage is likely less. But that is only US profits. With deindustrialization, industrial commodity production has shifted to the PRC, Indonesia, Vietnam, India, Brazil, Eastern Europe, and other low-wage areas and the US has become the center of world finance. If commodity production sneezes, the whole edifice of fictitious capital collapses, along with its fictitious profits.

As all three volumes of Capital explain in great detail, commodity production is the basis of the capitalist mode of production and wage-labor is the source of value, not the mystifying maneuvers of Wall Street grifters.

Garrido joins many leftist defenders of multipolarity in decoupling imperialism from the capitalist system, whether through revising the mechanism of exploitation, denying the logic of capitalist competition and rivalry, or redefining its characteristics. Garrido’s unique contribution to this maneuver is to locate the injustice of imperialism not in labor exploitation, but in “debt and interest”.

In the world of left multipolaristas, the real anti-imperialists are the BRICS states (for Garrido, Russia and the PRC). But for those of a lesser theoretical bent, for those reluctant to go into the weeds of theoretical debate, we have a handy litmus test: Palestine. If a genocidal assault on the Palestinian people by a greater-Israel theocratic state is the signal imperialist act of this moment, where are these anti-imperialists? Have they organized international opposition, stopped trade, imposed sanctions, withdrawn recognition or cooperation, sent volunteer fighters, or otherwise offered material resistance?

In the past, Chinese and Soviet material, physical aid benefited Vietnam fighting imperialism; the Soviets pushed to the brink of war to support Cuba against imperial threats in the early 1960s; the Cubans fought and died in Angola against imperialism and apartheid in the 1970s and 80s. Even the US joined the Soviet Union in thwarting British, French, and Israeli imperial designs on the Suez Canal in 1956.

Will today’s acclaimed “anti-imperialists” step up or is multipolarity all talk?

Greg Godels

zzsblogml@gmail.com

http://zzs-blg.blogspot.com/2025/09/imp ... stine.html

It is a continuing source of frustration that an important segment of the left holds the view that weakening the United States’ long-established grip on the top rungs of the hierarchical system of imperialism is-- in itself-- an attack on imperialism.

Many of our friends, including those who claim to aim at a socialist future, mistakenly see an erosion in the US position as the imperialist system’s hegemon as necessarily a step guaranteeing a just future, lasting peace, or a step towards socialism.

While it is true that those fighting the most powerful nation-state in the imperialist system for sovereignty, for autonomy, for a path of their own choosing always deserve our enthusiastic and complete support, victory in that fight may or may not secure a better future for working people. They may, as happened so often in the anti-colonial struggles of the post-war period, find themselves cursed with a power-hungry, exploitative, undemocratic local ruling class continuing or expanding the oppression of the people, but maybe with a more familiar face.

Or they might suffer the replacement of a former, declining or defeated great power by another more powerful great power. Germany and Turkey, defeated in World War I, lost many of their colonies to the victors; after World War II, some of Japan’s colonies were recolonized, falling into the clutches of another superior power; and, of course, Vietnam defeated France, only to be oppressed into the US sphere of interest-- a result decisively overturned by heroic Vietnam.

To contend that the decline or fall of the US as the leading great power in the imperialist system could close the book on imperialism is to grossly misunderstand imperialism. Imperialism lingers as a stage of capitalism as long as monopoly capitalism exists.The ultimate battle against imperialism is the struggle against capitalism.

We must not confuse the participants in the global imperialist system with the system itself, any more than we should equate individual capitalist corporations with the capitalist system itself.

History offers no example of a global or semi-global power falling or removed from the heights of its domination leading to a period of world-wide peace and prosperity. Neither the fall of the Roman or the Eastern Roman Empire or the Holy Roman Empire ushered in such a period of harmony. Nor did the rise and fall of the Venetian Republic, the Dutch Republic, or the Portuguese or Spanish colonial empires of the mercantilist era. In Lenin’s time, the rivalries challenging Britain’s global dominance brought world war rather than peace. And its aftermath brought no harmony. Instead, capitalist rivalries with Germany and Japan generated even more devastating aggression and war. And with the dissolution of the once dominant British Empire after the war, the US assumed and brutally enforced its position at the top of the hierarchy of global powers.There is no reason to believe that matters will change with the US knocked off its reigning perch. Capitalism and its tendency toward war and misery persist.

Thus, history provides no evidence for the supplanting of a unipolar world with a sustainable multipolar capitalist world of mutual respect and harmony. Multipolarity alone, as a solution to the oppression of imperialism, is, in fact, never found in world history.

Of course it may be factually true that United States dominance of the world imperialist system may be on the wane. Certainly, the decisive defeat in Vietnam was an enormous setback to the US government’s ability to dictate to weaker states. Further the defeat in Afghanistan after a twenty year war shows a weakening. The defiance of the DPRK and Cuba’s resilience also show limitations to US imperialism today.

Further, the rise of Peoples’ China as an economic powerhouse and as a sophisticated military power is perceived by the US government as both an economic and military adversary, though there is no reason to believe that the PRC presents any greater threat to the imperialist system than does the Papal State. Both today express well-deserved outrage at the worst excesses of imperialism, but make little material contribution to its overthrow.

Marginalizing, weakening, or defanging the arch-imperialist power is to be welcomed, though the left should suffer no illusion that the action would be an end to imperialism, a decisive blow against the capitalist system, or of long-lasting benefit of working people.

A recent example of the multipolarity fallacy-- the romantic illusion that imperialism is only US imperialism-- is the many leftist reports on the early September meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) attended by President Xi, President Putin, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and other Eurasian leaders. Professor Michael Hudson enthused that:

The principles announced by China’s President Xi, Russian President Putin and other SCO members set the stage for spelling out in detail the principle of a new international economic order along the lines that were promised 80 years ago at the end of World War II but have been twisted beyond all recognition into what Asian and other Global Majority countries hope will have been just a long detour in history away from the basic rules of civilization and its international diplomacy, trade and finance.

Hudson foresees a new economic order fulfilling a promise made eighty years ago. But he doesn’t tell us how a new capitalist international order will be different from the earlier capitalist international order, apart from the idealistic words of its advocates. He doesn’t explain how the inter-imperialist rivalries associated with capitalist great powers are to be avoided. He fails to show how the competitive, cut-throat nature of capitalist social-relations can be somehow tamed. He builds his case around high-minded words uttered at a conference, as if those or similar words were not uttered eighty years ago at the Bretton Woods conference.

Much has been made of the warm announcement by Xi and Modi that they are “partners not rivals”. But as the insightful Yves Smith relays:

A new Indian Punchline article, India disavows ‘Tianjin spirit’, turns to EU, reviews the idea that India is jumping with both feet into the SCO-BRICS camp is overdone. Key section from that post:

….no sooner than Modi returned to Delhi, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar had lined up the most hawkish anti-Russia gang of European politicians to consort with in an ostentatious display of distancing from the Russia-India-China troika.

To underscore the skepticism of the Indian Punchline article, Modi chose not to attend the virtual BRICS trade summit subsequently called by Brazilian President Lula da Silva.

In his place, minister Jaishankar chose the occasion to raise the issue of trade deficits with BRICS members, noting that they are responsible for India’s largest deficits and that India is expecting to secure a correction-- hardly a gesture of mutual confidence in India's BRICS brothers and sisters. It is more an example of geo-political bargaining.

Nor does Peoples’ China embrace the romantic idealism of our leftist friends”, as the following quote asserts:

“China is very cautious about working with these two countries [Russia and PDRK]. Unlike what is depicted in the West as them being allies, China is not in the same camp. Its view of warfare and security issues is very different from theirs,” said Tang Xiaoyang, chair of the department of international relations at Tsinghua University, pointing out that Beijing hasn’t fought a war for more than four decades. “What China wants is stability on its borders.”

One might conclude that the left’s hope in a BRICS led new, more just international order is little more than a chimera. BRICS appears to be, at best, an opportunistic economic alliance, with neither the political or military weight to press multipolarity on a unipolar world.

*****

There is. as well, a theoretical argument for a left investment in the idea of multipolarity as an answer to imperialism. It is an old argument. It was crafted by Karl Kautsky and advanced in an article entitled Ultra-imperialism and published in Die Neue Zeit in September, 1914, just a month after the beginning of World War I.

In short (I deal with the arguments more fully here, here, and here), Kautsky argued that the great powers would divide the world up among themselves and resolve to avoid further competition and rivalry. They would recognize the irrationality and counterproductiveness of aggression and war, opting for a harmonious imperialism that Kautsky called “ultra-imperialism”. He maintained that:

The frantic competition of giant firms, giant banks and multi-millionaires obliged the great financial groups, who were absorbing the small ones, to think up the notion of the cartel. In the same way, the result of the World War between the great imperialist powers may be a federation of the strongest, who renounce their arms race.

Similarly, today’s multipolaristas/ultra-imperialists envision a world in which a covey of powerful countries will expel the US from its leadership of the global capitalist system for its bad behavior, with its EU satrapy falling in line. In its place, they will create a new “harmonious”, “win-win” order that will eliminate the inequalities between the “global north” and the “global south”. The en-actors and enforcers of this new order will be a motley crew of class-divided, capitalist-oriented states led by an equally motley crew, including despots, theocrats, and populists. All but one of the BRICS+ espouse anything other than a firm allegiance to capitalism; most are hostile to any alternative social system like socialism.

Lenin, in a 1915 introduction to Bukharin’s Imperialism and World Revolution, mocked Kautsky’s argument and ideas like ultra-imperialism:

Reasoning theoretically and in the abstract, one may arrive at the conclusion reached by Kautsky… his open break with Marxism has led him, not to reject or forget politics, nor to skim over the numerous and varied political conflicts, convulsions and transformations that particularly characterise the imperialist epoch; nor to become an apologist of imperialism; but to dream about a "peaceful capitalism." "Peaceful" capitalism has been replaced by unpeaceful, militant, catastrophic imperialism… In this tendency to evade the imperialism that is here and to pass in dreams to an epoch of "ultra-imperialism," of which we do not even know whether it is realisable, there is not a grain of Marxism… For to-morrow we have Marxism on credit, Marxism as a promise, Marxism deferred. For to-day we have a petty-bourgeois opportunist theory -- and not only a theory -- of softening contradictions (quoted in my article cited above)

The key relevant thoughts here are “peaceful capitalism”, “Marxism on credit”, and “softening contradictions”. Lenin is shocked at Kautsky-- a self-styled Marxist-- even entertaining the notion of a peaceful capitalism, an idea that violates the very logic of capitalist social relations; it should be a wake-up call to multipolaristas.

“Marxism on credit” is a mockery of the notion that counting on some hoped for agreement between capitalist great powers to tame imperialism is as foolish as running your credit card to its limit. For multipolaristas, it is pushing the day of reckoning with capitalism off into the far, far distant future.

Likewise, Kautsky “softens” the contradiction between rival capitalist states by imagining an impossible agreement to guarantee “harmonious” relations, a proposition Lenin completely rejects. Concisely, Lenin sees Kautsky’s opportunism as a retreat from the socialist project. The same can be said for the multipolarity project.

Far too many on the left refuse to look at multipolarity through this lens of Lenin’s theory of imperialism, especially as expressed with considerable clarity in his 1916 pamphlet, Imperialism.

Regarding the promise of multipolarity, Lenin here offers a hypothetical scenario where imperialist powers do manage to cut up the world and arrive at an alliance dedicated to peace and mutual prosperity. Would that idealized multipolar system-- what Kautsky calls “ultra-imperialism”-- succeed in eliminating “friction, conflicts and struggle in all and every possible form”?

The question need only be stated clearly enough to make it impossible for any other reply to be given than that in the negative… Therefore in the realities of the capitalist system, and not in the banal philistine fantasies of English parsons [Hobson], or of the German “Marxist,” Kautsky, “inter-imperialist” or “ultra-imperialist” alliances, no matter what form they may assume, whether of one imperialist coalition against another, or of a general alliance embracing all the imperialist powers, are inevitably nothing more than a “truce” in periods between wars. Peaceful alliances prepare the ground for wars, and in their turn grow out of wars; the one is a condition for the other, giving rise to alternating forms of peaceful and non-peaceful struggle out of one and the same basis of imperialist connections and the relations between world economics and world politics. [Lenin’s emphasis]

Thus, while capitalism persists, Lenin makes the case for unabated intra-class struggle on the international level, struggles that manifest as inter-imperialist rivalry and war.

Of course it is possible to reject Lenin’s argument, even Lenin’s theory of imperialism. It is also possible to praise Lenin’s views as relevant for its time, but inapplicable today, in light of the many changes in global capitalism. That would be to say that the system of imperialism that Lenin set out to analyze no longer exists, replaced by a different system.

There is a precedent for correcting Lenin’s theory. Kwame Nkrumah, writing in 1965, showed that imperialism had largely abandoned the colonial project in favor of a more rational, efficient, but still brutally exploitative form of imperialism: neo-colonialism. His book, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism makes that case persuasively.

One cannot assume that Lenin’s is the final word on today’s imperialism.

And that is the tactic that Carlos Garrido takes in his recent essay, Why Russia and China are NOT Imperialist: A Marxist-Leninist Assessment of Imperialism’s Development Since 1917. Garrido ambitiously explores many subjects in this brief essay, including the errors of “Dogmatic Marxist-Leninists”, the place-- if any-- of Russia and the PRC in the imperialist system, Marxist methodology, the contemporary status of finance capital, Michael Hudson’s notion of super imperialism, the significance of Bretton Woods and the abandonment of the gold standard, as well as the relevance of Lenin’s theory of imperialism to today’s global economy.

Addressing all of these issues would take us far away from the current discussion, though they deserve further study.

To the point, he writes:

It appears to me that the imperialist stage Lenin correctly assessed in 1917 undergoes a partially qualitative development in the post-war years with the development of the Bretton Woods system. This does not make Lenin “wrong,” it simply means that his object of study – which he correctly assessed at his time of writing – has undertaken developments which force any person committed to the same Marxist worldview to correspondingly refine their understanding of imperialism. Bretton Woods transforms imperialism from an international to a global phenomenon, embodied no longer through imperialist great powers, but through global financial institutions (the IMF and the World Bank) controlled by the U.S. and structured with dollar hegemony at its core.

He adds that with Nixon’s move from the gold-standard, “imperialism becomes synonymous with U.S. unipolarity and hegemonism.”

This is wrong. As Garrido affirms, “Imperialism [in Lenin’s time] was not simply a political policy (as the Kautskyites held), but an integral development of the capitalist mode of life itself.” [my emphasis]

Likewise imperialism today is not a set of political policies, but an essential expression of contemporary capitalism.

Yet Garrido follows Kautsky in confusing today’s imperialism with a set of political policies: Bretton Woods and the US withdrawal from the gold- standard. The entire post-war trade and financial infrastructure was the result of policy decisions. They were shaped not by a “new” imperialism, but by the overwhelming economic power of the US after the war. As Garrido knows, that asymmetry is being challenged today, but it is a challenge to the policies or the power enjoyed by the US and not to the imperialist system.

The “transformation” that Garrido believes he sees is simply a reordering of the international system that existed before the war with New York now replacing London as the financial center of the capitalist universe. It is the replacement of the vast colonial world and the bloody rivalries and shifting alliances and hierarchies of the interwar world with the creation of a neo-colonial system dominated by the US and reinforced by its assumption of the role of guardian of capitalism in the Cold War. The monopoly capitalist base is qualitatively the same, but its superstructure changes with historical circumstances. The Bretton Woods system and the later discarding of the gold standard reflect those changing circumstances.

How does Garrido’s “new” imperialism function?

What matters is that capitalism has developed into a higher stage, that the imperialism Lenin wrote of is no longer the “latest” stage of capitalism, that it has given way – through its immanent dialectical development – to a new form marked by a deepening of its characteristic foundation in finance capital. We are finally in the era of capitalist-imperialism Marx predicted in Volume Three of Capital, where the dominant logic of accumulation has fully transformed from M-C-M’ to M-M’, that is, from productive capital to interest-bearing, parasitic finance capital.

Garrido’s reference to volume III of Capital would seem to be at odds with mine and others’ reading of that volume. In chapter 51, the last complete chapter, Marx, via Engels, brings matters back to the beginning, to commodity production. He dispels the view that there is any independent source of value in distribution-- in circulation, rent or “profit”. It is wage labor in commodity production that produces value in the capitalist mode of production. That is why Marx notes in Volume III that “The real science of modern economy only begins when the theoretical analysis passes from the process of circulation to the process of production.” (Vol. III, International Publishers, p.337).

Of course Marx acknowledges stock markets and would not be shocked by the financial sector's suite of exotic instruments like derivatives and swaps. Marx explains them under the rubric: "fictitious capital”. By “fictitious” Marx means forward-looking-- promissory notes against future value or “bets”. They circulate among capitalists and are acquired as contingent value. They become attractive in times of overaccumulation-- the super-concentration of capital in few hands-- when investment opportunities in the productive economy grow slim. And they disappear miraculously when the future that they depend upon does not materialize.

Garrido’s misunderstanding of the international role of finance capital leads him to make the claim that “...the lion's share of profits made by the imperialist system are accumulated through debt and interest.” At its peak before the great crash of 2007-2009, finance (broadly speaking, finance, insurance, real estate) accounted for maybe forty percent of US profits; today, with the NASDAQ techs, the percentage is likely less. But that is only US profits. With deindustrialization, industrial commodity production has shifted to the PRC, Indonesia, Vietnam, India, Brazil, Eastern Europe, and other low-wage areas and the US has become the center of world finance. If commodity production sneezes, the whole edifice of fictitious capital collapses, along with its fictitious profits.

As all three volumes of Capital explain in great detail, commodity production is the basis of the capitalist mode of production and wage-labor is the source of value, not the mystifying maneuvers of Wall Street grifters.

Garrido joins many leftist defenders of multipolarity in decoupling imperialism from the capitalist system, whether through revising the mechanism of exploitation, denying the logic of capitalist competition and rivalry, or redefining its characteristics. Garrido’s unique contribution to this maneuver is to locate the injustice of imperialism not in labor exploitation, but in “debt and interest”.

In the world of left multipolaristas, the real anti-imperialists are the BRICS states (for Garrido, Russia and the PRC). But for those of a lesser theoretical bent, for those reluctant to go into the weeds of theoretical debate, we have a handy litmus test: Palestine. If a genocidal assault on the Palestinian people by a greater-Israel theocratic state is the signal imperialist act of this moment, where are these anti-imperialists? Have they organized international opposition, stopped trade, imposed sanctions, withdrawn recognition or cooperation, sent volunteer fighters, or otherwise offered material resistance?

In the past, Chinese and Soviet material, physical aid benefited Vietnam fighting imperialism; the Soviets pushed to the brink of war to support Cuba against imperial threats in the early 1960s; the Cubans fought and died in Angola against imperialism and apartheid in the 1970s and 80s. Even the US joined the Soviet Union in thwarting British, French, and Israeli imperial designs on the Suez Canal in 1956.

Will today’s acclaimed “anti-imperialists” step up or is multipolarity all talk?

Greg Godels

zzsblogml@gmail.com

http://zzs-blg.blogspot.com/2025/09/imp ... stine.html

"There is great chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent."

Re: Ideology

Considerations regarding the programs of communist parties

The program of a Marxist party must be more than just a document, but a living guide to action, defining the strategic and tactical goals in the struggle for communism. It serves as the ideological core, cementing all the multifaceted activities of a working-class party, subordinating organizational development, strategy, and tactics to the ultimate goal—the construction of a communist society.

The program must be a theoretical continuation and development of the "Manifesto of the Communist Party," the "Critique of the Gotha Program," and other programmatic works by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. It must also be a continuation and development, in a broad sense, of the Lenin-Stalin program. And, of course, it must exclude everything that led to the collapse of communism in the USSR.

And the modern experience of the CPC and the WPK demonstrates that without a scientifically based and principled program, the party cannot be a unified, monolithic organism capable of consistently defending its line in the face of a constantly changing situation and fierce class struggle.

The modern era, characterized by a deepening general crisis of capitalism and new challenges to communism, confirms Lenin's enduring truth: the struggle for the purity of Marxist-Leninist theory has been and remains the decisive condition for the success of the working class. It is the program that accumulates in clear, verified formulations everything that has been theoretically substantiated, summarized, and tested by the practice of class struggle, including both historical experience (the USSR) and contemporary achievements (the Workers' Party of Korea, the Communist Party of China, the Communist Party of Vietnam, and other parties in power). Every idea in the program must be formulated to serve the communist struggle and motivate forward movement.

The party program is not dogma, but it is inviolable. It is a concise formulation of theory. The specific objectives of a given stage of the class struggle lose their urgency as they are resolved, so the program evolves. If changes in reality are not adequately reflected in the program, it is effectively supplemented by decrees of governing bodies and speeches by leaders. This was the case under Stalin, when the formalism of democratic centralism, coupled with the objective political complexities of the pre-war, wartime, and post-war periods, hindered the program's updating.

Scientific centralism can be defined as the unquestionable authority of leaders during their lifetimes: Stalin in the USSR, the Kims in North Korea, and Xi Jinping in China. It is these leaders who formulate programmatic provisions, complementing the formal party program. They ensure the unity of theory and action, the development of decisions based on in-depth analysis, and unconditional discipline in their implementation, preventing the party from falling behind reality and the program from becoming an abstract declaration.

Stalin, by the way, noted that if the constitution records the gains, then the program is what must be won.

The core, unshakable tenet of any genuine Marxist program has been and remains the proposition that the dictatorship of the working class is a necessary condition for the transition to communism. At one time, the program of the RSDLP was the only one to pose this question with revolutionary frankness, while the parties of the Second International, sliding into opportunism, either ignored it or openly rejected it. Modern opportunists and revisionists, like their predecessors, attempt to emasculate this fundamental tenet of Marxism, replacing it with abstract arguments about democracy (including workers' and proletarian democracy), which conceal a reliance on spontaneity (khvostism). The experience of the CPC and the WPK convincingly demonstrates that only firm state power of the working class , exercised through various forms of popular sovereignty, is capable of suppressing the resistance of overthrown exploiters, defending the gains of communism, developing productive forces, and building a new society. Firm state power exercised by the party led by communists .

The experience of the USSR, China, North Korea, Cuba, Vietnam and other socialist countries shows that the more actual democracy there is, the closer the collapse of power and the party .

The rejection of the dictatorship of the working class, no matter the pretext, inevitably leads to the restoration of capitalism, as demonstrated by the bitter fate of the USSR and several Eastern European countries. Scientific centralism in party structure protects against opportunistic degeneration and guarantees the implementation of the dictatorship, preventing the erosion of the class essence of power and ensuring the implementation of the general line .

The historical struggle over the Bolshevik program that unfolded at the Second Congress of the RSDLP now appears, from the vantage point of the past century, not simply as an intra-party dispute, but as a fundamental clash of two irreconcilable methodologies—revolutionary and opportunist. The essence of this confrontation is crystal clear: can the working class, led by its party, become the hegemon of the historical process, or is it doomed to remain an appendage of the bourgeois system, fighting only for short-term economic concessions.

Lenin's position, brilliantly formulated in "What Is to Be Done?" and further developed by Stalin, was that a spontaneous workers' movement inevitably falls under the influence of bourgeois ideology and the bourgeoisie. The task of a new type of party, however, is to be an active agent, instilling communist consciousness in the proletarian masses, channeling their struggle into a consistent revolutionary struggle for political power. It was precisely this role of a conscious vanguard that opportunists of all stripes, from Martynov to Trotsky, rejected, in fact opposing the doctrine of the dictatorship of the working class.

Doesn't this sound familiar? Martynov said:

“In the development of modern socialism, layers of the working class, varying in their level of consciousness, reached, practically and gropingly, individual problems and solutions that their ideologists discovered, synthesized, and theoretically substantiated.”

Against Stalin's position:

"The labor movement must unite with socialism; practical activity must be closely linked with theory, thereby giving the spontaneous labor movement a social-democratic meaning and physiognomy... We, Social Democrats, must prevent the spontaneous labor movement from following a trade unionist path; we must guide it into a social-democratic channel, infuse this movement with socialist consciousness, and unite the advanced forces of the working class into a centralized party. Our duty is to always and everywhere lead the movement, energetically combating all—be it enemy or 'friend'—who stand in the way of achieving our sacred goal."

AND:

“The spontaneous development of the workers’ movement,” wrote Lenin, “is heading precisely towards its subordination to bourgeois ideology… Our task, the task of social democracy, is to combat spontaneity, to divert the workers’ movement from this spontaneous striving for trade unionism under the wing of the bourgeoisie and to draw it under the wing of revolutionary social democracy.”

Opportunism places precisely the same bet on spontaneity today, affirming, praising, and extolling party democracy while rejecting scientific centralism! This isn't so difficult to understand if one grasps the essence of opportunistic spontaneity.

The modern experience of leading communist parties, such as the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK) and the Communist Party of China (CPK), confirms Lenin's and Stalin's—that is, scientific-centralist—positions. Their successes are based, firstly , on the unconditional primacy of the party as the guiding and directing force of the state and society, consistently implementing scientific theory rather than drifting with the tide of spontaneous processes; secondly , on unconditional subordination to the leaders. The principle of scientific centralism, in this case in the form of the leaders' authority, ensures unity of will, thought, and action, and is a direct legacy and development of the organizational principles championed by the Bolsheviks in their struggle against the "Economists" and "Mensheviks."

The historical experience of developing and fighting for the Bolshevik program serves as an enduring lesson for the communist movement. It teaches that a program is not a rigid document, but a living guide to action, based on fidelity to the principles of Marxism-Leninism and their creative application to specific historical conditions.

At the same time, the historical experience of the Bolshevik Party program and the experience of modern communist parties shows that the updating of the program occurs through the programmatic directives of the leaders. Even in the DPRK, additions and amendments to the WPK program were not so frequent, despite the dramatic changes in the global situation that directly impacted the construction of communism.

Our experience is that the de facto program for breakthroughism is currently the complex of the most fundamental works, primarily by V.A. Podguzov. That same Breakthrough Minimum .

It is completely natural that no guidelines can cancel the provisions of dialectical materialism and everything that constitutes the main thing in Marxism-Leninism.

An important aspect of the Marxist understanding of the party program is Lenin's thesis from 1920 that the plan for the electrification of the country - GOELRO - became the second program of the party!

"Our party program cannot remain just a party program. It must become a program for our economic development; otherwise, it is useless as a party program. It must be supplemented by a second party program, a work plan for reconstructing the entire national economy and bringing it up to date with modern technology. Without an electrification plan, we cannot move on to real construction."

This is an example of when the leaders’ guidelines complement the party’s program.

A remarkable decision in every sense of the word was the decision of the 19th Congress of the CPSU to consider “Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR” as an equal supplement to Stalin’s work program.

The program is an important component in connecting theory with specific people and in the process of setting slogans for the struggle.

The history of the Stalinist and post-Stalinist periods of the CPSU reveals that, with regard to the topic under discussion, party members were divided into two categories: for those whose program was a simple policy document demanding recognition (often in words), and for those whose program was a laconic expression of Marxist-Leninist theory (with the actual program supplemented by the leaders' programmatic documents). What was the primary purpose of the program as a document for true communists? Propaganda! A communist, program in hand, went to the masses to clearly demonstrate the fundamental conclusions of the class struggle, its goals, and its prospects.

Thus, in scientific centralism, the program's function has shifted toward propaganda. The program should not be the only thing that unites party members. Unity must be ensured by a correct understanding of the program, that is, a unified tract theory, dialectical theory . The program remains a powerful propaganda weapon.

A. Mashin, with the participation of A. Redin

, 09/30/2025

https://prorivists.org/109_programm/

The program of a Marxist party must be more than just a document, but a living guide to action, defining the strategic and tactical goals in the struggle for communism. It serves as the ideological core, cementing all the multifaceted activities of a working-class party, subordinating organizational development, strategy, and tactics to the ultimate goal—the construction of a communist society.

The program must be a theoretical continuation and development of the "Manifesto of the Communist Party," the "Critique of the Gotha Program," and other programmatic works by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. It must also be a continuation and development, in a broad sense, of the Lenin-Stalin program. And, of course, it must exclude everything that led to the collapse of communism in the USSR.

And the modern experience of the CPC and the WPK demonstrates that without a scientifically based and principled program, the party cannot be a unified, monolithic organism capable of consistently defending its line in the face of a constantly changing situation and fierce class struggle.

The modern era, characterized by a deepening general crisis of capitalism and new challenges to communism, confirms Lenin's enduring truth: the struggle for the purity of Marxist-Leninist theory has been and remains the decisive condition for the success of the working class. It is the program that accumulates in clear, verified formulations everything that has been theoretically substantiated, summarized, and tested by the practice of class struggle, including both historical experience (the USSR) and contemporary achievements (the Workers' Party of Korea, the Communist Party of China, the Communist Party of Vietnam, and other parties in power). Every idea in the program must be formulated to serve the communist struggle and motivate forward movement.

The party program is not dogma, but it is inviolable. It is a concise formulation of theory. The specific objectives of a given stage of the class struggle lose their urgency as they are resolved, so the program evolves. If changes in reality are not adequately reflected in the program, it is effectively supplemented by decrees of governing bodies and speeches by leaders. This was the case under Stalin, when the formalism of democratic centralism, coupled with the objective political complexities of the pre-war, wartime, and post-war periods, hindered the program's updating.