The working class in Mexico, a first statistical approach

HÉCTOR MARAVILLO, MEMBER OF THE FJC POLITICAL BUREAU 18.Aug.14 Virtual library

Introduction

Nowadays it is common to find speeches according to which talking about the working class is an anachronism. Whether from the academy the death of the proletariat is theoretically argued, or from the? Left? talk about the "new emerging subjects", all agree in denying their existence and / or their revolutionary potential.

And yet the workers continue daily coming to their work and producing the material base of society; To paraphrase Galileo Galilei: ?? and yet they move ??. In this sense, the Slovenian philosopher SlajovZizek is right in exhibiting as a current phenomenon the need to remove the production process from the public eye, as if it were an? Obscene indecency? something to be done ?? underground ??. In this way, while Western countries can afford to babble about the "disappearing working class," there are "millions of anonymous workers sweating in third world factories". (one).

Although each of these discourses appears with different nuances and foundations, they tend to coincide on one or more of the following points:

?? The nonexistence of the working class or its tendency to disappear, in quantitative terms. For example, the theories of deindustrialization, outsourcing, the growth of the middle class, the increase of social mobility, etc.

?? The displacement of the capital-labor contradiction as the guiding and explanatory axis of the social economic system. For example the theories about ?? post ?? societies. (post-capitalist, post-industrial, post-Fordist), the knowledge economy. As Zizek would say, this is the postmodern way of rejecting the importance of class conflict (2)

?? The disappearance of the revolutionary capacity and political potential of the working class. For example, when talking about the "new emerging subjects", the struggle of the "citizen".

At other times there have been criticisms from Marxism-Leninism to the different positions that they try to ?? assassinate ?? theoretically to the working class. For example, the book by Peter Mertens (member of the Belgian Labor Party) The working class in the era of multinationals (3), where he criticizes the fallacies of Antonio Negri about the ?? disappearance of the working class ?? and it shows that the growth of the tertiary sector is not at the expense of the proletariat, as argued, but of the rural population. In a more limited sense, his article can be reviewed for the International Communist Magazine (4) or, in the case of Mexico, the article by comrades Jesús Saavedra and Miguel Kun from number 3 of El Machete (5). Following this line, in this little work,

To speak of the working class in its totalities, it is necessary to consider it in its opposition to other classes, because as Marx and Engels would say in The German Ideology? Different individuals only form a class as soon as they are forced to sustain a common struggle against another class. , because otherwise they themselves confront each other, hostilely, on the level of competition ?? (6). But this does not mean that subjective factors (?? class for itself ??) cannot be abstracted and focus only on their objective determinations (?? class itself ??); always considering them as indissoluble but analytically separate moments. Gramsci correctly describes these different moments or levels of the study of the class struggle under historical materialism in his text Analysis of Situations. Relationship of forces ??:

?? 1] A relationship of social forces closely linked to the structure, objective, independent of the will of men, and that can be measured with the systems of the exact or physical sciences. On the basis of the degree of development of the material forces of production, we have social groupings, each of which represents a function and occupies a given position in production itself. This relationship is, and nothing else: a rebellious reality; no one can modify the number of companies or their employees, the number of cities with the corresponding urban population, etc. This fundamental strategic division makes it possible to study whether the necessary and sufficient conditions for a transformation exist in society, that is,

2] A later moment is the relationship of political forces, that is: the estimation of the degree of homogeneity, self-awareness and organization reached by the various social groups. This moment can be analyzed in turn by distinguishing in it various degrees that correspond to the various moments of collective political consciousness as they have manifested themselves up to now in history. (??)

3] The third moment is that of the relations of the military forces, which is the immediately decisive one in each case. (??) two degrees can be distinguished, the military in the strict sense, or technical-military, and the degree that can be called political-military. ?? (7)

We would place ourselves at the first level, by carrying out an analysis of the working class in quantitative terms, based on the data offered by the latest state censuses in our country. Statistics are used here only to give an idea of the economic and quantitative importance of the working class, that is, to speak of it in terms of its potentiality according to its objective conditions; Well, as Lenin would warn ?? Statistics should illustrate the socio-economic relationships established with a complete analysis, and not become an objective in itself (8).

The development of the concept of the working class

The most general notion of the working class or proletariat is that given by Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifestoas the class of modern wage laborers, who, deprived of their own means of production, are forced to sell their labor power in order to exist? (9). This definition has its limits. Being the most general expression of the development and contradictions of capitalism, the existence of the other classes in transition that are supposed to be disappearing has been abstracted. But in our country this class structuring is not shown in its pure state - or anywhere else - but rather in a motley juxtaposition and mixture of situations that prevent us from seeing the working class at first. Keeping the initial definition in this context would only serve to hide the essence of the concept, and politically fall into serious errors of confusion. For example, could be reached the absurdity of considering soldiers or company managers as? proletarians? for the simple fact of being salaried workers, without analyzing the social function they fulfill.

Marx explains in the first volume of Capital that "from an economic point of view, he can only be called" proletarian ". the salaried worker who produces and values (capital) ?? (10). This adds a determination to the concept that you did not previously have. Not only is it enough to know its relationship with the means of production and the type of property it has, it is necessary to take into account the ?? position in the production process ?? What is it that defines how is the ?? articulation of society in classes ?? (11) In this way, following the characteristics that Lenin mentions to locate a social class, the workers are characterized by being:

?? Salaried workers. That is, they receive the part of the social wealth that corresponds to them through wages.

?? People ?? free ?? in two senses, free from all ownership of the means of production and free to sell their labor power for a living.

?? Direct producers, that is, they have ?? a more or less direct intervention in the handling of the object on which the work falls ??; Although depending on the degree of capitalist development, they do not need to have a direct manual intervention, it is enough to be part of the ?? organ of the collective worker, to execute any of its divided functions ?? (12).

?? Their place in the production system is that of being productive workers in the capitalist sense; that is, in addition to producing merchandise, they must (directly) produce surplus value for the capitalist (13). This excludes, for example, the production of goods by the artisan or production for self-consumption.

So far it is clear that the workers, technicians and assistants of the different branches generally considered as secondary sector, belong to the working class; we refer to mining (14), the production and distribution of electricity, water and gas, construction and manufacturing industries. However, there are a series of economic branches that are commonly considered to be of the tertiary sector, such as “services”, but that in a strict sense, are as capitalist as the previous sectors.

To explain this it is necessary first to understand the difference between the sale of labor power and a service. The difference lies in the fact that while in the first case, what the worker sells is his work capacity to integrate himself as a living factor into the production process; in the second case, what he sells is the product of his labor as action, but which is consumed as use value, not to be incorporated into the capitalist production process. The buyer is interested in the product or the execution of the specific work, and not in increasing his capital (15).

Strictly speaking, the production of surplus value, supposes the production of merchandise, and therefore the objectification of labor in? Products separable from the workers? that they exist independently of themselves as autonomous commodities? (16). However, it may be the case where the useful effect of a commodity is inseparable from its production process, it can only be consumed during it. This would be the case of the communications industry, which in Marx's time was the only one with economic importance, including the specific industry of transporting people and goods such as the mere transmission of news, letters, telegrams, etc. . ?? (17). Currently we could include the electrical industry, the telephone industry - telecommunications in general - or the hotel and restaurant industry.

This is the general definition of the concept of the working class. But so far we started only from the point of view of production, missing to consider the distribution process, and its dynamics as a whole, which ends up unfolding the concept. Furthermore, as Marx explained throughout Capital and mainly in the unpublished Chapter VI , capitalism is in constant change, therefore it is possible to historically locate different ?? phases ?? of capitalist development, for example, formal or real subsumption, which ends up modifying and contributing new elements to the concept of the working class.

Let's start with the first situation. Until now, the definition had only considered production, based on the contradiction between capital-labor, expressed in the relationship between industrial capital and the industrial worker. And it was assumed that this capital and the worker were in charge of all the necessary functions, that is, not only of production but also of the realization of capital. However, historically the different functions of capital tend to unfold to complete the other moments of the capital cycle and fulfill the functions of commercial capital and money-capital. Of these new functions, we are interested in knowing what happens to your new workers. In this sense, Marx tells us in Volume III that

?From one point of view, this commercial worker is a salaried worker like any other. In the first place, because his labor is bought by the merchant's variable capital and not by money spent as income, this means that it is not bought simply for the private service of the purchaser, but for capital appreciation purposes. Second, because the value of their labor power and, therefore, their salary, is determined, as in other wage-earning workers, by the cost of production of their specific labor power and not by the product of his work.

However, between him and the workers directly employed by industrial capital must necessarily mediate the same difference as between industrial capital and commercial capital and that which exists, therefore, between the industrial capitalist and the merchant ?? (18)

Commercial workers are those workers who are dedicated to capturing surplus value (produced by their colleagues the industrial workers). He agrees with the other workers in selling his labor power to capital and not the product of his labor (a service). But, the commercial worker does not directly produce surplus value, therefore the circulation expenses that appear for the industrial capitalist (in which they are accounted for) appear as dead expenses. For the merchant, on the other hand, they are the source of his profit, therefore for the commercial capital his expenses in these workers supposes a productive investment, are they? For him [for the mercantile or commercial capital], a directly productive work? ? (19).

The fact that commercial workers belong to the working class by the first condition described, allows this to translate into the possibility of a joint struggle between salaried workers in commerce and industrial workers, for example, in a struggle for generalized increase of salary. As they are not direct producers of surplus value, but simply its captors, their salary does not have a necessary relationship with the mass of profit that it helps the capitalist to realize. What it costs the capitalist and what he gets out of it are two different magnitudes? (twenty). This situation generates a series of problems that hinder the development of their class consciousness and the organization of this stratum of workers. For example, As they are the best paid workers, they tend to spring up unionist political positions or close to the petty bourgeoisie. On the other hand, the unnecessary relationship between the profit of commercial capital and the salary of the commercial worker, causes the contradiction between them, to be generally indirectly based on a series of mediations, and not frankly and daily as between the worker and industrial capital.

Now if we approach things from the historical point of view, it is observed that there are a series of economic activities in which the factors of production act under the direction of capital ?? in order to obtain more money from money ?? (21), but without being under the properly capitalist technical base. For example, the case of the production of books, pictures, and in general of artistic products, which Marx considered as a ?? form of transition towards the only formally capitalist mode of production ?? (22). In this sense, we could include professors and doctors who are under the direction of capital in order to increase it; and in an even more rudimentary sense, pedicab, taxi or minibus gangs, under relationships in transition to capitalism. These sectors, strictly speaking,

There is a division that crosses the entire working class according to the technological base (technical-organizational) on which the particular production process is sustained, which constitutes the expression of the forms and phases through which the development of the capitalism in the industry of a specific country ?? (2. 3). The main phases of this development are three: small mercantile production (small industries, preferably peasant ones), capitalist manufacturing and the factory (large machined industry). Marx explains these phases in the fourth section of Capital (chapters 11, 12 and 13), of which Lenin makes an excellent synthesis:

??Small mercantile production is characterized by a completely primitive manual technique that has not changed almost since time immemorial. (??) Manufacturing introduces the division of labor, which brings about a sensible transformation of the technique, turning the peasant into an operator, into a “worker who makes specific pieces”. But manual production is preserved, and on its basis the progress of the modes of production is inevitably distinguished by great slowness. The division of labor occurs spontaneously, it is also adopted by tradition as peasant labor. Only the great mechanized industry takes a radical path, jettisons manual art, transforms production on new, rational principles, systematically applies the data of science to production. (??) Small mercantile production and manufacturing are characterized by the predominance of small companies, of which only a few large ones are engaged. The large machined industry definitely displaces the small companies. In small industries too, capitalist relations are formed (in the form of workshops with wage laborers and commercial capital), but they are weakly developed here and do not crystallize in sharp contrasts between the groups of people involved in production. Here there are still neither large capitals nor vast layers of the proletariat. In manufacturing we see the formation of one and the other. The gulf between the owner of the means of production and the worker is already reaching considerable proportions. (??) But the multitude of small companies, the preservation of ties with the land, the preservation of traditions in production and throughout the life regime, all of this creates a mass of intermediate elements between the extremes of manufacture and slows the development of these extremes. In large machined industry all these brakes disappear; the extremes of social contrasts reach higher development. It seems as if all the shadowy sides of capitalism are concentrated: the machine gives, as is known, an enormous impulse to the extension of the working day without measure; women and children are incorporated into production; the reserve army of the unemployed is formed (and according to the conditions of factory production), etc. But the socialization of work, which the factory carries out to an enormous extent,?? (24).

To each of these phases of development, corresponds a particular type of worker, thus there would be artisan or manual, manufacturing or workshop and factory workers (25). In addition to these large sectors of the proletariat, subgroups of workers can be classified based on the technical and organizational characteristics required by the different industrial branches and their specific production processes, for example between agricultural proletariat and transporters (26).

This logical-historical unfolding of the concept of the working class leads us to its most developed form, the industrial or factory worker, which in turn corresponds to large mechanized industry. It is only from this highest form of the working class that the concept can be understood in its full extent. Marx would say referring to this methodological principle that ?? The anatomy of man is the key to the anatomy of the monkey. Consequently, the indications of the higher forms in the lower animal species can be understood only when the higher form is known. The bourgeois economy thus provides the key to the old economy, etc. ?? (27). It is only in large machined industry where all the social contradictions of capitalism reach their maximum development, therefore, the class of factory or industrial workers,

Finally, the emergence of large industry opens the way to a new stratum of the working class, the industrial reserve army, as the other side of the coin. Marx explained in Chapter XXIII of Capital, how capitalist accumulation implied a relative decrease of variable capital in the face of constant absolute growth of the working population, that is, the appearance of a relative overpopulation, a working population that was excessive for needs. means of exploitation of capital ?? (29) This relative overpopulation occurs in different ways. On one side is the contingent of workers unemployed fluctuatingly according to the needs of capital (of its cycles) in some branch or region. On the other hand, those workers who are active but with a very irregular work base are also included, with a standard of living and a minimum wage and maximum working hours; thus becoming docile instruments of capital exploitation (30). The other two forms in which the reserve army presents itself (latent overpopulation; and the ?? ragged proletariat ?? or ?? lumpenproletariat ??) although they are also the result of capitalist accumulation, their elements do not constitute part of the working class, rather, its origin is the impoverishment of other social layers.

Conformation of the working class in Mexico

In the last population census, 112.3 million inhabitants were counted in our country (31). Of these, approximately 25% are children under 12 years of age, so (abstracting the 850,000 boys and girls between the ages of 5 and 13 who worked in 2009) we can assume that they live at the expense of the other 75% (32). In turn, of this 75%, only half, that is, 42 million, is the employed population, while the other half lives on pensions, remittances, government or family support, or bank interests. Without looking at the data from the point of view of ?? position at work ?? provided by official statistics, we can get a very general idea of the size of the working class, starting from the first definition, since 68% of the employed population is reported as salaried workers (28.8 million people); versus 3% (1.2 million) of ?? employers ?? and 24% of self-employed workers (10.3 million).

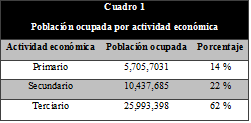

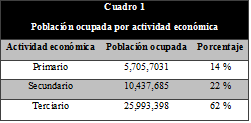

Regarding the workers producing surplus value (industrial workers), data are generally presented on the quantity and proportion of workers by large economic sectors to show the? Disappearance of the working class? and ?? outsourcing ?? economic, as in the following chart.

Under these data, it seems that the proportion of the working class is not very important, only a fifth. However, a study at this level tends to hide more than it reveals. It is necessary to go down in the analysis to the different economic branches to observe the importance of the different social groups of workers. In the following graph (33), the number of people employed by economic sector is represented, differentiating the role they occupy, either as workers and technicians (including subcontracted workers), as employees or as owners.

From here two issues are observed:

?? There are strictly industrial workers who are considered in the service sector by official statistics. For example, workers in the business support services sector. that mostly correspond to the branch? employment services ?? (outsourcing, outsorsing) which in turn are mainly found in the manufacturing industry; and a good part of the communication workers as mentioned above.

?? That service workers correspond to sectors that do not agree with the idea of "outsourcing the economy". For example, the sector with the most workers corresponds to ?? other services except government activities ?? and it has 2.6 million workers and technicians; of which 2 million belong to the branch ?? households with domestic employees ?? and about 300 thousand to the branch of ?? repair and maintenance of cars and trucks ?? (In this sector also highlights the branch ?? beauty salons, public baths and bolerías ?? with almost 200 thousand people employed). The other important sectors are the teaching profession, the bureaucracy, and health workers.

That is to say, that? Service society ??, of the ?? information age ?? or ?? postindustrial ??, would have its main representatives in the owners of grocery stores, workers in supermarkets or fast food chains, mechanics, repairmen of washing machines and irons or stylists.

From the data and the different characteristics of the strata of the working class considered in the previous section, we can build a first statistical approach of the number of people that each stratum groups.

In this way, at least 16 million people in Mexico (along with their families that we are not considering here) belong to the working class, which corresponds to 34 of the total employed population in 2008, and 43% of the total salaried workers in the country.

While its most developed nucleus, industrial workers represent 13% of the total number of employed persons. To these we could add other social groups that are on the borders of the working class:

Subcontracting (outsorsing): 2,062,009 million people (these may have been double counted by the elaboration methodology)

Teaching: 2,214,849 million people

Health, cultural and recreation workers: 1,133,157 million people

Industrial reserve army: more than 2.5 million people (35).

In total, these forms of transition or on the edge of the working class, add up to approximately 8 million people, that is another 17% of the total employed population.

Finally, from the point of view of economic importance, it stands out that production is the one that has the greatest contribution of value. For example, if industry is considered in its typical sense, as the sum of mining, construction, manufacturing and electricity, water and gas; It appears that it contributes 37% of the country's Added Value, and if transport and telecommunications are added to this, it reaches 45%. For its part, commerce only contributes 15% and banking matters (financial, insurance, real estate, corporate and professional services) reach 18%, while the rest of services add another 18%.

Concentration of industrial workers in the Valley of Mexico.

To illustrate what has been reviewed so far, the case of Mexico City and its metropolitan area can be analyzed; to show the importance and concentration of industrial workers.

The economic censuses register 560 thousand workers in the manufacturing industry, of which 317 thousand correspond to factory workers in companies with more than 101 employed persons. That is, 7% of all employed persons or 11% of salaried workers in the Valley of Mexico are factory workers in large companies, that is, at least 1 in 10 workers in the Metropolitan Area of the VM they are industrial-factory workers of the great machined industry.

But this is not all, not only do they represent an important proportion in terms of numbers, but also from the point of view of their economic contribution. For example, the large industry of the ZMVM (considered here, as a statistical approach, to companies with more than 101 employees) contributes 5% of the country's gross domestic product ($ 534,496 million); In other words, what is produced in the large industrial factories of Mexico City, exceeds the total gross production of states such as Guanajuato or Coahuila. This illustrates the degree of concentration of capital and workers there is with respect to the number of companies, where a small number of factories employ the majority of industrial workers and contribute most of the production of their branch.

Regarding the concentration of workers and industrial capital geographically, two maps are offered with the distributions by workplace and by housing area. This way you will be able to locate the regions of labor concentration, both those people who ?? do not see ?? to the workers they can go looking for them, as for those who commonly carry out political work with the workers know where to concentrate their batteries.

The first map represents the distribution of industrial factories (with more than 101 employed persons) as white points, which in turn assumes a distribution of workers by workplace. In turn, the bars by municipality and delegation reflect the type of company they are in. The black bars are the number of workers employed in factories with more than 501 workers, while the white bars are those in factories with 101 to 500 workers.

Based on the map and the information provided by the 2009 economic census and the Statistical Directory of Economic Units (DENUE), we know that:

?? The highest industrial concentration is found in the north of the city, followed by the east and south of the DF, and finally a dispersion of factories in the center and the southeast.

?? The northern zone is divided into three corridors that follow the transport routes, and stands out in branches of food processing, chemicals, plastics, automotive and electronic products. In the first place, the area constituted by the junction of the Tlalnepantla, Azcapotzalco and Naucalpan corridors (to a lesser extent the Miguel Hidalgo and Atizapán de Zaragoza delegation). In total there are 168 thousand industrial workers. This area is the one that contributes the most industrial added value in Mexico City and the one that concentrates the most industrial workers, having as its center the Pantaco railway terminal, the most important nationwide. Next, the corridor around the México-Querétaro highway that crosses the municipalities of Tultitlán, Cuautitlán Izcalli and part of Tepotzotlán and Cuautitlán stands out. This zone concentrates 23 thousand factory workers with more than 501 employed persons. Finally, there is the Ecatepec corridor, around the Vía Morelos, with the second place in added value of the ZMCM and with the highest concentration of industrial workers of more than 1001 employed persons (more than 9,000 thousand workers).

?? The East zone (Iztapalapa and Iztacalco) has several industrial parks, Iztapalapa being the territorial delimitation that concentrates the most industrial workers per workplace (more than 70 thousand), however most of the companies are medium or small in size. The predominant branches are food processing, textile factories and maquilas of metallic or electrical products.

?? The southern zone (Xochimilco, Coyoacán and part of Tlalpan) has a low concentration of workers working (24 thousand in the first two mentioned delegations), however a third of these are in factories with more than 1001 employed persons (8 thousand ). These companies are mainly pharmaceutical companies that are located around the Tlalpan Calzada Light Rail line and correspond to the second zone of the ZMCM that provides the most added value.

?? There are much smaller industrial zones around the highway to Toluca (Cuajimalpa) and around the highway to Puebla (La Paz, Ixtapaluca and linked to these in Chalco). These are presented as future poles of industrial growth, but for the moment they are insignificant compared to the other areas. In addition, there is a great dispersion of factories in the downtown area of the DF (Benito Juárez, Cuahutémoc) that correspond mostly to textile maquilas and printing companies.

Regarding the workers according to their place of residence, an estimate has been made represented in the following map. For this, the employed population by Basic Geostatistical Area (AGEB) was multiplied with the percentage of workers in each delegation with respect to the total of its employed population. It is based on the assumption that the proportion of workers per AGEB is homogeneous in each delegation; Although this is not necessarily true for all boundaries, it does allow us to get an idea of the areas where there is a greater concentration of workers.

Starting from the map, where the darker areas represent more workers per AGEB, and vice versa, a lighter gray corresponds to a lower number of industrial workers; the following observations can be obtained:

?? The areas with the highest concentrations are in the periphery. In the municipalities of the State of Mexico that surround the Federal District. And to a lesser extent in the inner periphery of the Federal District, forming a south arch and a north arch.

?? The areas where the greatest concentration of workers is observed in a smaller area is in Nezahualcóyotl-Chimalhuacán (160 thousand workers altogether) and in Ecatepec (163 thousand).

?? In second place, the areas of labor concentration on the outskirts of the city stand out. Mainly in the southeast (Chalco, Valle de Chalco, Ixtapaluca, 103 thousand workers) and various areas in the northeast of the Federal District, with an interval of between 33 thousand and 80 thousand workers per municipality (Nicolás Romero, Atizapán, Tlalnepantla, Cuautitlán Izcalli and Tultitlán)

?? Within Mexico City, the areas are more dispersed and with less density due to AGEB; mainly in Iztapalapa and Tláhuac (190 thousand workers). Then Azcapotzalco and Gustavo A. Madero (118 thousand), and finally a southern arch from Álvaro Obregón to Xochimilco (154 thousand).

Combining the observations of the analysis of the distribution of industrial workers by workplace and place of residence, the following hypotheses can be suggested:

?? The most strategic area in terms of labor concentration (in the two aforementioned senses) is the northeastern corridor, which begins in Azcapotzalco and ends in Tepotzotlán, around the road to Querétaro and with its respective branches. By concentrating workers in factories and in the colonies, it can be assumed that it is a space where a directly proletarian discourse crystallizes. Ecatepec has characteristics similar to the previous zone, only limited to a single municipality; therefore we can assume the same as for the previous point. We name this set of areas as the northern region.

?? On the other hand, the south-east region has a lower concentration and density of industrial plants (a pharmaceutical corridor in Coyoacán-Xochimilco, a concentration center in Chalco-Ixtapaluca and a dispersion of industrial parks in Iztapalapa-Iztacalco-Tláhuac). In turn, the concentration of population by place of residence has not been so marked (except for Nezahualcóyotl-Chimalhuacán), rather it is distributed throughout the delegation, this makes it difficult to carry out a work focused on certain areas. Therefore, we can suppose that in this region the popular urban discourse in the colonies and towns is more likely to have greater acceptance.

?? Finally, the central region of Mexico City is the one with the greatest dispersion of workers, which is why it is irrelevant in any planning of political work with the workers, compared to the other two regions.

Bibliography

(1) Zizek, S. (2000). Welcome to the desert of the real.

http://comunidadmecs.files.wordpress.co ... textos.pdf , 7-8.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Mertens, P. (2011). The working class in the era of multinationals. ?? Jaime Lago ?? Cultural Association,

http://www.jaimelago.org/sites/default/ ... nacionales. pdf .

(4) Mertens, P. (2012). The end of the working class ?, International Communist Magazine. 3,

http://www.iccr.gr/site/es/issue3/the-e ... class.html .

(5) Saavedra J. and Kun M. (2013) The end of the working class? A Study on the composition of the working class in the State of Mexico, El Machete, 3, 24-35.

(6) Marx, C. and F. Engels (1974) The German Ideology. Mexico: Popular Culture.

(7) Gramsci, A. (1981). Political writings (1917.1933). Mexico: XXI century, 346-349.

(8) Lenin, VI (1957). The development of capitalism in Russia. The process of the formation of an internal market for large industrialists. Buenos Aires: Cartago, 506.

(9) Marx, C. and F. Engels. (1978). Manifesto of the Communist Party. Moscow: Progreso, 30.

(10) Marx, C. (1999a). Capital: Critique of Political Economy I. 3rd ed. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 518

(11) Lukács, G. (1969). History and class consciousness. Grijalbo: México, 49

(12) Marx, C. (1999a), 425.

(13) ?? Within capitalism, only the worker who produces surplus value for the capitalist or who works to make capital profitable is productive. (??) The concept of productive work does not simply entail a relationship between the activity and its useful effect, between the worker and the product of his work, but also implies a specifically social and historically given relationship of production, which converts the worker into a direct instrument of capital appreciation. ”Ibid., 426.

(14) Although this sector produces an income, it also generates a production of surplus value.

(15) Vid. Marx, C. (1985a). Capital Book I Chapter VI Unpublished. 12th ed, Mexico: Siglo XXI, 80

(16) Ibídem, 78 y 85.

(17) Marx, C. (1999b). 50-51.

(18) Marx, C. (1959). Capital: Critique of Political Economy III. 2nd ed. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 256.

(19) Ibídem, 293-294.

(20) Vid. Ibid, 293: ?? This salaried worker does not pay the capitalist directly by creating surplus value, but by helping him to reduce the costs of realizing the surplus value, doing the work, partly unpaid, necessary for this ??

(21) Marx, C. (1985a). 54.

(22) Ibídem, 88. Own underlining.

(23) Lenin, VI (1957). 456.

(24) Ibid., 542

(25) Marx, C. (1999a). 373

(26) ?? For example Lenin for the situation of 1899 classified Russian wage workers into the following categories: 1) agricultural wage workers, 2) factory, mining and railway workers, 3) construction workers, 4) Laborers , loaders, workers in the lumber industry, workers in excavation and laying of railways, and 5) workers employed at home in a capitalist way? Lenin, VI (1957). 578-579

(27) Marx, C. (1985b). General Introduction to the Critique of Political Economy 1857. 13th ed. Mexico: XXI century, 55-56.

(28) Vid. Lenin, VI A great initiative.

(29) Marx, C. (1999), 533.

(30) Ibid, 544-545

(31) INEGI. (2010). Population and Housing Census 2010.

(32) INEG-I (2009). Child labor

(33) The data from the Input Product Matrix carried out by INEGI in 2008 has been used, and not the data from the Economic Census of the same year. While the MIP-2008 does not work with ?? real data ?? but with the estimate of the number of workers that the branch employs per year. Its advantage lies in considering temporary, subcontracted and informal workers, therefore its total number (47.4 million) is closer to the 42 million employed persons registered by INEGI in its 2010 Population and Housing Census. 2009 Economic Census, although it works with real values of employed personnel, its own methodology restricts it to only 20 million employed persons, leaving a bias of 22 million unaccounted for.

(34) Workers are considered to be those who are classified in the statistics as? Technical workers? and ?? staff supplied by another company name ??. As for industrial workers, the following sectors are included: Mining. Electric power, water and gas. Manufacturing Ind. Transport, mail and storage ?? except freight auto transport-. Information in mass media.

(35) The National Survey of Employment and Employment estimated 2.5 million unemployed people and 5.9 million people ?? not economically active ?? but available, that is, the week before the survey they were neither working nor looking for work.

(36) Marx, C. (1999b) Capital: Critique of Political Economy II. 3rd ed. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 50-51

(37) Marx, C. (1999a) .373.

Texto completo en:

http://elcomunista.nuevaradio.org/la-cl ... tadistico/

http://elcomunista.nuevaradio.org/la-cl ... tadistico/

Google Translator