Amilcar Cabral and the South Africans

Posted by INTERNATIONALIST 360° on JANUARY 25, 2023

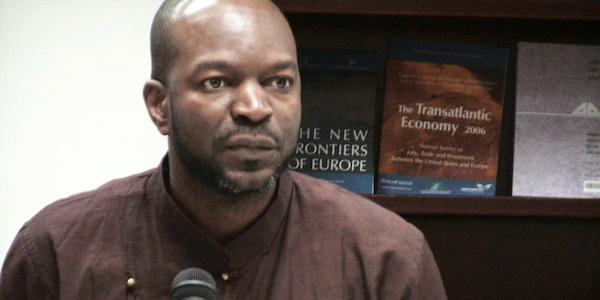

Phethani Madzivhandila

Amilcar Cabral’s influence stretched far beyond the Portuguese colonies, profoundly influencing the political struggle in South Africa, past and present.

In 2021, the South African government was provided with funding of around €700 million (ZAR13 billion), from the German government to decommission its coal-based power stations in order to transition to green energy. True to their hypocritical nature, the Germans quickly reverted back to coal-fired plants when Russian president Vladimir Putin stopped supplying Russian gas to the rest of Europe. This dynamic is terribly familiar to countries of the global south. The Guinea-Bissauan revolutionary, Amilcar Cabral, already said in 1971: “Imperialism—as you know better than myself—is the result of the gigantic concentration of financial capital in capitalist countries through the creation of monopolies, and firstly of the monopolies of capitalist enterprises.”

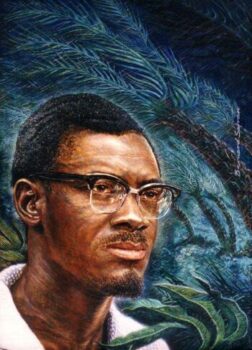

Cabral was assassinated, in January 1973, by fascist Portuguese just months before the PAIGC (Guinea Bissau’s anticolonial movement) succeeded in achieving Guinean independence. His influence at the time reached beyond Portugal’s colonies in Africa (he had a hand in the formation of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, MPLA, and the Liberation Front of Mozambique also known as FRELIMO). He also inspired other liberation movements which combined mass and armed struggle in Southern Africa, especially in South Africa. There, the Pan-Africanist Congress and African National Congress of South Africa were contemporaries of the PAIGC and fashioned themselves in the same image, though not with the same success. Cabral also influenced the Black Consciousness Movement, led by Steve Biko.

At the time of Cabral’s murder, Yusuf Dadoo, a leading ANC ideologue, wrote about Cabral’s life lessons for the ANC and its allies. “Cabral saw the task of the national liberation movements as not merely to usher in Black rule replacing white faces with black ones; it was not only to raise a different flag and sing a new anthem but to remove all forms of exploitation from the country.” Dadoo added, “ Cabral was careful to distinguish the color of men’s skins from exploitation and repeatedly emphasized that the struggle was against Portuguese colonialism and not against the Portuguese people.”

Biko, who emerged as a political leader around the time Cabral was murdered, would himself die at the hands of apartheid police in 1977. Drawing parallels between these two anti-colonial thinkers one cannot help but notice how their insistence on using culture as a tool of anti-colonial mobilization was a key component of their political thinking. For Cabral it was vital that for people to free themselves of foreign domination they must first understand their own culture and that of the oppressor. Biko, in turn, argued that culture must be defined in concrete terms. “We must relate the past to the present and demonstrate the historical evolution of modern Africa. We must reject the attempts by the authorities to project an arrested image of our culture.”

These days, it is clear that the kind of cultural revolution desired by Cabral and Biko is less straightforward and fraught with appropriation. As the Angolan anthropologist Antonio Tomas puts it, Cabral’s life and work illustrates the striking gap between “revolutionary hopes and postcolonial realities.” In post-1994 South Africa the comprador bourgeoisie in the ANC have betrayed the people’s sacrifices and aspirations for their own material benefit. This present class of leaders plays the intermediary role between the first world and the third world—they facilitate oppression on behalf of their masters in the first world. At the same time, they are also bound to co-opt revolutionary ideals in service of their own economic advancement. South Africa’s energy minister, Gwede Mantashe, has described the worldwide pressure to decarbonize as a colonial, anti-fossil fuel agenda. It’s one thing to take aim at the double-standards of global elites, but it is another thing—as Mantashe has—to call opposition to land dispossession for extractivism by rural communities “apartheid and colonialism of a special type.”

As the academics Maurice Taonezvi Vambe and Abebe Zegeye summarize, what Cabral sought through cultural renaissance was “first and foremost a people’s renewal.” Unless culture sinks its roots into the creative humus of people’s experience, the discourses of Africa’s renaissances that are authored by Africa’s elite will surely wilt.

This is a key postcolonial dilemma: how to cultivate a truly mass, national culture. It was arguably #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall that first challenged the post-apartheid cultural order by exploding the myth that the new South Africa had brought equality and opportunity. The ideology of rainbowism that founded this myth was imposed from on high. But, as Cabral emphasized, “Culture is not a superstructure, but is deeply rooted in the economic and social reality of a people.”

The question, therefore, cannot be answered in the abstract, and has to be grounded in the real struggle for emancipation waged by the people. Franz Fanon, just like Cabral, would later predict that the leaders of national liberation movements on assuming power would seek to fill the shoes of colonial masters and oppress the rest of the population. Still, Cabral believed that the post-independence role of the petty-bourgeoisie leadership holds the key to the potential of successful revolutionary socialism in the continent.

Any serious electoral politics from the African left must confront this terrain. Much as the labor movement and social movements are the bread and butter of successful left-wing political organizations, the precarious middle classes on the continent are an important constituency to target. It is this group that has the most reason to be disgruntled with the vagaries of neoliberalism, having originally been promised that the integration of Africa into global capitalism would issue steady economic growth and furnish all with opportunity for security and flourishing.

Yet it is precisely this that renders the petty bourgeoisie contradictory: on the one hand, disillusioned with the promise of individual success made by contemporary capitalism, and on the other, allured by it. In Cabral’s words, it is “a vacillating class, with one foot in the camp of the bourgeoisie and the other foot in the camp of the proletariat.” The #FeesMustFall moment planted the seeds of revolutionary consciousness across the burgeoning, professional managerial class, but these were quickly snuffed by the pressures to join the labor market and adopt individual strategies of pursuing upward social mobility. Fees Must Fall activist Lufefe Sopazi, notes that it was Cabral’s legacy and dedication to liberation that inspired them to remember that the struggle for liberation was not over and it was betrayed as the lives of the majority of the African people in South Africa were not liberated.

Nonetheless, the task of a revitalized left in Africa is to appeal to the middle class squeezed by neoliberalism. In Africa, the working class lacks the sufficient numbers to constitute a formidable political force. A counter-hegemonic coalition requires the vast ranks of the unemployed and under-employed, as well as progressive wings of the middle class. As junior partners of these broad-based coalitions, enthusiastic youth can bolster movements with their energy, capacity, and technical skills, as Cabral did in Guinea-Bissau.

For South Africa, 29 years after democracy, the question of post-apartheid remains an illusion, reinforced and spurred by native elements controlling political or state power. It remains an illusion because the ruling class as predicted by Cabral in Tell No Lies, Claim No Easy Victories is subjected to the whims and impulses of imperialists. This pseudo bourgeoisie, however, strongly nationalist during the struggle for liberation, cannot fulfill a historical function; “it cannot freely guide the development of productive forces, and in short, cannot be a national bourgeoisie.” Evidence in South Africa today points to the inevitable destiny of another failed state, as we have witnessed in the past few years the total collapse of state owned enterprises such as PRASA (the passenger rail service), SAA (the national carrier) and Eskom (the state power utility).

For Cabral, national liberation is the restoration of a people’s historical personality through the eradication of imperialist domination. In South Africa, this has not yet been realized. He argued that only when the national productive forces are entirely liberated from all forms of dominance can there be national liberty. National liberation must acknowledge the right of the people to have their own history because imperialism usurps it via violence.

Any liberation organization that ignores this is undoubtedly not engaged in national liberation. That is the challenge for South Africa now.

https://libya360.wordpress.com/2023/01/ ... -africans/

Empire by Invitation: Pax Africana or Pax Americana?

Posted by INTERNATIONALIST 360° on JANUARY 25, 2023

Samar Al-Bulushi

(Photo by OLIVIER DOULIERY / AFP) (Photo by OLIVIER DOULIERY/AFP via Getty Images)Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, left, and U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, right, attend a welcoming ceremony before talks at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 15, 2022.

AT A WIDELY anticipated summit hosted by the Biden administration in Washington, D.C., last month, African leaders called for more support from the U.S. government for counterterrorism efforts on the continent. Aware that the Biden administration has woken up to the geostrategic significance of Africa in the context of Russia’s war with Ukraine, a number of the heads of state in attendance approached the gathering as a political marketplace in which loyalties are bought and sold. All signs indicate that elite pacts in the name of “security” will continue to dominate U.S.-Africa relations, with ordinary people caught in the crosshairs of newly emboldened U.S.-trained security forces.

Forty-nine African leaders convened in Washington for the U.S.-Africa summit, the first such gathering hosted by the U.S. since 2014. At the Peace, Security, and Governance panel on December 13, Presidents Filipe Nyusi of Mozambique, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud of Somalia, and Mohamed Bazoum of Niger joined African Union Chair Moussa Faki Mahamat in appealing for more U.S. security and counterterrorism aid.

The speeches delivered by each of these leaders poignantly illustrated what some might refer to as “empire by invitation,” wherein ostensibly sovereign leaders reproduce colonial power relations by inviting a more expansive role for imperial actors in their own affairs.

This is clearest in Somalia, where Mohamud recently asked the U.S. to loosen restrictions on its drone strikes targeting al-Shabab, despite documentation of, and lack of accountability for, the rise in civilian deaths due to drone strikes. “Not only does AFRICOM utterly fail at its mission to report civilian casualties in Somalia,” Amnesty International noted in 2020, “but it doesn’t seem to care about the fate of the numerous families it has completely torn apart.” While the Biden administration initially went to great lengths to suggest that it would curb former President Donald Trump’s lenient approach to drone warfare in Somalia by imposing more restrictions on the U.S. Africa Command, it continues to grant the military considerable leeway and has yet to publicly reject Mohamud’s request.

In the midst of a catastrophic food crisis, Mohamud has declared war on the Somali population by calling on all civilians to leave al-Shabab-controlled territory, warning that they risk becoming collateral damage if they do not physically distance themselves from the group. Mohamud’s approach amounts to a form of collective punishment, as his government is holding the entire population responsible for the actions of a small minority. Given that so many have already been displaced by drought and war, the assumption that further relocation is even possible shows a callous disregard for the challenges confronting ordinary Somalis.

The Somali president’s privileging of military solutions aligns perfectly with the primary interest of the Biden administration: addressing what it perceives to be threats to national and international security. Panelists such as Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, and Samantha Power of the U.S. Agency for International Development approached political dynamics in Africa — whether in the form of hunger, unemployment, outward migration, popular protest, or coups — through the lens of risk and instability, rather than as the product of a longstanding scramble for African resources and a market-oriented global economy that has exacerbated marginalization and inequality.

The overarching message was that economic desperation and political frustration should be understood as threats that call primarily for one kind of solution: containment, and, if necessary, the use of violent force. None of the speakers on the Peace, Security, and Governance panel acknowledged that, particularly since the establishment of AFRICOM, the U.S. has in many ways contributed to the very instability it claims to want to solve, with the rise of al-Shabab in the aftermath of the 2006 U.S.-backed Ethiopian invasion of Somalia a case in point.

(Photo by SAUL LOEB / AFP) (Photo by SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images)

Members of the National Guard block the streets near the site of the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit in Washington, D.C, on Dec. 13, 2022.

Pax Africana or Pax Americana?

IN HIS REMARKS at the summit, Mahamat highlighted the efforts made by the African Union to establish its own security architecture. Noting that the continent’s national armies are “underequipped,” he stressed the importance of having permanent special forces at the continental level that would be “more flexible” and “more offensive” in their approach.

Mahamat was referring to the African Standby Force, a mechanism that has yet to become fully operational. Championed for its potential to offer “African solutions to African problems,” the extent to which such a force will in fact be African-led is the source of considerable debate. At a time when the U.S. is wary of the costs associated with its own direct intervention — whether in dollars, lives, or legal and political blowback — the Pentagon’s Africa Command increasingly relies on a growing number of African security forces to assume the burden of counterterrorism missions on the continent. Partnerships with elite African military units allow U.S. forces to rely on proxies in cases where America is not officially at war and where the very presence of U.S. troops is likely to raise eyebrows. For their part, African states’ readiness to deploy their own troops to the front lines has been critical to their continued ability to access development assistance and foreign aid.

The idea for a U.S.-trained, all-African military force was first proposed by the Clinton administration in the 1990s. Referred to at the time as the African Crisis Response Force, the Clinton plan came in the wake of the U.S. military’s painful exit from Somalia in 1993, which precipitated a shift in U.S. strategy away from a boots-on-the-ground approach to military intervention. Instead, the U.S. sought to cultivate partnerships with African militaries that could be trained and equipped for security operations, all while protecting U.S. interests. In the words of Nigerian scholar Adekeye Adebajo, “Africans would do most of the dying, while the U.S. would do some of the spending to avoid being drawn into politically risky interventions.”

At the time, some of the continent’s most vocal leaders were circumspect. Presidents Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Nelson Mandela of South Africa rejected the notion of such a force on the basis that Africans had not been consulted about the proposal. President Muammar Gaddafi of Libya saw the writing on the wall, presciently anticipating what would eventually become AFRICOM. At a 1999 summit of the Organization of African Unity (the predecessor of the African Union), Gaddafi instead proposed the creation of a continental army that would explicitly serve the purpose of protecting Africa from the meddling of external neocolonial powers.

In doing so, he rekindled an older proposal by Ghana’s anti-colonial leader and eventual president, Kwame Nkrumah, who in the 1960s called for the creation of an African Military High Command to protect African states in the face of interference from Western powers. Despite formal declarations of independence across the continent at the time, Nkrumah was mindful of the potential for new forms of colonialism to compromise African sovereignty, contributing to the rise of client states and of “exploitation without redress.” As he wrote in 1965: “For us, the best or worst shout against imperialism, whatever its form, is to take up arms and fight. This is what we are doing, and this is what we will go on doing until all foreign domination of our African homelands has been totally eliminated.”

An archival photo shows a pin-back button promoting the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party, founded by Kwame Nkrumah in 1968.

Ultimately, neither Nkrumah’s nor Gaddafi’s visions came to fruition. In the early days of independence, many African leaders worried about the potential for such a force to challenge the sovereignty of their newly independent states, and many held differing viewpoints on the question of intervention during the crisis in the Congo, which became a battleground for influence between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

In the early 2000s, the African Union did establish its own security architecture, but in doing so, it abandoned the principle of noninterference long upheld by its predecessor, the Organization of African Unity. In an amendment to Article 4(h) of the Constitutive Act of the African Union, the union now has the right to intervene in member states when there is a “serious threat to legitimate order” for the purpose of restoring peace and stability.

What explains the shift away from Nkrumah’s preoccupation with external (neocolonial) aggression to the African Union’s seemingly open-ended embrace of intervention in the name of protecting “legitimate order”? Perhaps the first and most obvious answer is that both Nkrumah and Gaddafi were removed from power, and Gaddafi was killed by NATO-backed Libyan forces.

In 1966, one year after Nkrumah wrote about the need for Africans to arm themselves in the struggle against ongoing foreign domination, he was deposed in a military coup orchestrated by the CIA. According to the U.S. State Department at the time, Nkrumah’s “overpowering desire to export his brand of nationalism unquestionably made Ghana one of the foremost practitioners of subversion in Africa.” These events sent a clear message to other African leaders, many of whom had assumed power just a few years prior.

The potential operationalization of an African Standby Force comes with an important set of questions, including whether such an entity can constitute a form of pan-African cooperation that is by and for Africans, or whether it functions as a cover and a tool for militarism and endless wars that serve imperial interests.

Despite the summit’s rhetorical emphasis on democracy and open societies, the U.S. continues to view the continent through the lens of threat and great power rivalry — particularly as it faces increasing competition from China, Russia, Turkey, and the Gulf states. Looking ahead, we can expect that AFRICOM will continue to rely heavily on its African partners to function as militarized extensions of U.S. power on the continent, even as it rehashes the myth that instability in the region remains a “local,” Africa-specific problem. The extent to which African leaders at the summit displayed their readiness to serve as alibis for this charade is cause for deep concern.

https://libya360.wordpress.com/2023/01/ ... americana/

**************

Targeting Eritrea and Ethiopia: The Warmongering Campaign of Disinformation

The National Council of Eritrean-Americans NCEA 25 Jan 2023

2022 Conference of National Council of Eritrean Americans (Photo: Eritrean Ministry of Information)

Washington think tanks are home to the propagandists who help guide US foreign policy decisions. The National Council of Eritrean Americans highlights the words of one individual who uses his position as a think tank fellow to repeat disinformation regarding Eritrea. He and others like him make the case for interventions and interference around the world.

United States plans for aggression and disruptions abroad are developed by current and former officials whose names may not be well known. They often leave government positions to become fellows at a plethora of think tanks that are connected to high level policy makers. It is important to know what they are saying, as their words have an impact on US foreign policy decisions.

Michael Rubin is currently a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) , the rightwing think tank in Washington, DC, that mostly disseminates a neoconservative interventionist agenda, and where Rubin spends his time churning out misleading information and lies about the Red Sea State of Eritrea and the Horn of Africa. Rubin was a Pentagon staffer from 2002 to 2004, and an advisor to the Coalition Provisional Authority during America’s disastrous invasion of Iraq in 2003. He also claims to have spent time with the Taliban before 9/11. The misinformation and disinformation in both cases cost the lives of many Americans and led to a disastrous foreign policy for people in those nations. Since the Tripartite Agreement of Comprehensive Cooperation between Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia was signed on 5 September 2018, Rubin seems to be obsessed with the Horn of Africa.

It’s this Michael Rubin who is now leading a concerted campaign of disinformation against Eritrea. Rubin was among the American neoconservatives who pushed the US into war in Iraq in 2003 based on a series of lies. He is also a man with a “bounty of three million Turkish lira , or nearly $800,000, placed on his head” in connection with the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt for "supporting and committing offenses for the Fethullahist Terror Organization,'' an Islamist movement led by Fethullah Gülen. He exemplifies the links between official Washington and think tanks that masquerade as neutral observers.

Presently, Rubin as representative of those Western forces who are targeting Eritrea for sanctions and “regime change”, has found it expedient “to kill three birds with one stone” in the Horn of Africa region: regime changes in Eritrea as well as Ethiopia and keeping Somalia in a state of perpetual chaos. Though he has written many lies about Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali and Somalia’s ex-president Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed “Farmaajo”, his worst vitriol is reserved for Eritrea and its President Isaias Afwerki. He is obsessed with ageism when it comes to the Eritrean leader. While the current president of the US is an octogenarian, and about 10% of US senators are 76 years old or higher, Rubin loves to harp on about President Isaias’s age, and repeats TPLF’s lies and ill-wishes about President Isaias, who is in good health.

Michael Rubin is a representative of those who don’t want to see peace in the Horn of Africa, whether between Eritrea and Ethiopia or within the Somali nation as it struggles to emerge from decades of chaos and state collapse. Here is what he wrote about the former:

“Indeed, it is not certain Abiy’s détente with Eritrea will last, nor that Ethiopia itself will remain stable and unified. Alas, Abiy appears to have let the [Nobel peace] prize go to his head and, in doing so, may have forgotten an important rule of peacemaking: timing matters. Sometimes rushed reconciliation regardless of the good intentions behind it can lead to disaster.”

To Rubin and others who work to influence US policy, a peace deal between Eritrea and Ethiopia after twenty years of war and hostilities is considered “rushed.” In fact, at one time, he encouraged the Tigrayan terrorist group, TPLF, to invade Eritrea and as he did in Iraq twenty years ago, he promised them they would be received with flowers in Eritrea. His own words :

“The question now is whether Tigray Defense Forces will enter Eritrea to end a regime that was as much an aggressor against Tigray as Ethiopia’s Army but with even less legal justification. Isaias is old and in ill health. His people are demoralized. The rapid defeat of Eritrean forces in Tigray shows his weakness. Should the Tigray Defense Forces enter Eritrea or, more likely, organize and support Eritrean opposition forces, Isaias may find his own conscript army will dissolve and defect.”

Rubin also condemned the news of peace between the two Somalias:

“It has now been almost 30 years since Somalia descended into state failure. … Abiy, however, has decided that his Nobel mantle gives him a mandate single-handedly to reunite Somalia. Last week, Abiy brokered the first-ever meeting between Muse Bihi Abdi, Somaliland’s president, and Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed Farmaajo. Abiy likes Farmaajo for the same reason Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan and U.S. Ambassador Donald Yamamoto do: because he is not known for an independent intellect and is pliable to their needs.”

Since February 2019, Rubin has written over 40 articles maligning and openly calling for regime change in Eritrea. His articles covered subjects ranging from accusations against the Eritrean president of considering “attacking Somaliland in order to gain a port on the Red Sea” and maligning the Ethiopian Prime Minister stating he intends to “keep Ethiopia in a state of perpetual crisis” to maintain power. In addition to his sinister intentions relating to Eritrean and Ethiopian people and their leaders, these statements expose his ignorance of the area . First, Somaliland doesn’t share a common border with Eritrea; second, it is not located on the Red Sea coast but along the western side of the Indian Ocean.

As Rubin knowingly recycled and regurgitated discredited stories about Eritrea as a panelist at a conference on “Reshaping Africa’s Narratives: The Media in Perspective” in Kigali, Rwanda, on 14 May 2021. Dr. Frederick Golooba-Mutebi, a Ugandan Professor Extraordinarius at the Archie Mafeje Research Institute at the University of South Africa had this rebuke to the likes of Michael Rubin:

“Everything that I knew about Eritrea came from the western media. I read a lot about Eritrea in all the major western newspapers and I never heard or read a single positive thing about that country … [So], I decided to go to Asmara and see Eritrea, talk to Eritreans, and talk to Eritrean leaders and try to understand what kind of country Eritrea is. I can tell you that I came out of Eritrea feeling extremely angry. I was angry about all the stuff I had read about Eritrea and believed. … There are so many things that happen in Eritrea which I think are very good things that the rest of us in Africa should know about, but which no one tells us about, absolutely no one.”

[Dr. Golooba-Mutebi visited Eritrea in 2018 and you can read what he wrote for The East African about what he found in Eritrea:

Eritrea, the 'police state' where there are no cops to be seen (September 7, 2018)

https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/op ... en-1401900

Ignore the naysayers, Asmara is not reclusive and is open for business (October 1, 2018)

https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/op ... ss-1403636

You can see of what he said at the Reshaping Africa’s Narratives: The Media in Perspective panel starting at the 35:45 minute mark at

https://youtu.be/I7eJgT47m1s .

Rubin, however, didn’t care to take Mutebi’s eyewitness warning into consideration. Instead, he set out to promote Eritreans like Ahmed Chalabi to help him fabricate stories like what he did with the nonexistent “WMDs” in Iraq. Ahmed Chalabi was the Iraqi quisling who was the disinformation agent feeding the “WMD” and other lies to his US handlers in order to create pretext for US invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Along with these Eritrean Chalabists, Rubin is recycling an old, discredited story of “slavery in Eritrea.” Of course, there is no slavery in Eritrea. It is Eritrea’s National Service that Rubin is maliciously misrepresenting as “slavery.” A national service that doesn’t spare the president’s or ministers’ children from serving their nation is twisted out of context and labeled as “slavery." If an honored service to one’s country and people is referred to as slavery, then millions who serve their countries around the world under national service programs are “slaves." National Service is not unique to Eritrea; nearly one-third of world nations have some form of national service. Furthermore, calling Eritrean National Service as “slavery” whitewashes the heinous crimes of slavery and minimizes the genocide that was committed on Africans during the Middle Passage and in the hands of slave owners in the Americas.

The battle for Africa is raging, with the US, China, Russia, Europe, and other countries vying to influence the many resource-rich countries of the continent. The US, in particular, has also been engaged in dangerous militarization of the continent through its Africa Command, AFRICOM, which has now established military bases in some form or the other in all the African countries except Eritrea. Unfortunately the barrage of misinformation and disinformation have been used as pretext and excuse to impose sanctions on Eritrea. Destabilizing Eritrea based on lies and misinformation will not benefit the people of Eritrea or the world. Rubin and others of his ilk have influence in Washington; US foreign policy will inevitably repeat the same aggressions it has committed in the past.

Rubin and AEI exemplify how imperialist think tanks work hand in hand with the US government, be it in Iraq, Iran, South Caucasus, Turkey, Syria or Yemen. They are now frantically attempting to derail peace efforts in the Horn of Africa. Our hope is that this cycle of interventions will end, and that these campaigns of disinformation about Eritrea and its neighboring countries will end too.

https://www.blackagendareport.com/targe ... nformation

AFRICOM Watch Bulletin #44

US Out of Africa Network 25 Jan 2023

January 8, 2023 ceremony where U.S. presented $9 million in military supplies to the Somali National Army (Photo: courtesy AFRICOM Facebook page)

The Black Alliance for Peace AFRICOM Watch Bulletin discusses the first session of the UN Permanent Forum on People of African Descent and provides updates on the latest news from the African continent.

This article was originally published in the Black Alliance for Peace website.

The United Nations recently held the first session of the Permanent Forum on People of African Descent in Geneva, Switzerland. From December 5-8, more than 600 delegates from UN member states, UN structures, and civil society took the floor to call for global recourse and the institutional protection of human rights for Africans all over the world.

Established in August 2021, during the 7th year of the UN International Decade for People of African Descent—spanning 2015 to 2024—the Permanent Forum will act as an advisory body to the UN Human Rights Council. The UN General Assembly declared the Forum also will serve as “a consultative mechanism for people of African descent and other relevant stakeholders” and “platform for improving the safety and quality of life and livelihoods of people of African descent.”

The convening consisted of international and virtual pre-events and side events that discussed the human rights situation of Africans on the continent, as well as Africans in Europe, and what we call “Nuestra América,” the landmass encompassing what is now known as Canada to the tip of Chile. Representatives from the Black Alliance for Peace (BAP) and BAP’s U.S. Out of Africa Network (USOAN) attended the December convening to:

*engage in political struggles around the establishment of this forum—which are discussed in this month’s interview;

*reach out to and build international structures (significant numbers of folks from the global South were in attendance); and

*focus on issues of militarization and its impact on African people.

BAP and the USOAN emphasize the increased militarization of the African continent and Nuestra América, as well as its implications for resistance efforts by local communities and activists, as a key part of the war on African people. We seek to build the mass movement necessary to defeat it.

U.S. Out of Africa: Voices from the Struggle

AFRICOM Watch Bulletin speaks with Mama Efia Nwangaza, who is the Founder/Director of the Malcolm X Center for Self Determination, member of the Black Belt Human Rights Coalition Criminal Punishment System Sub-Committee as well as the Black Alliance for Peace, and a veteran of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC):

AFRICOM Watch Bulletin: What are your thoughts on the Permanent Forum?

Efia Nwangaza: The Permanent Forum on People of African Descent, December 5-8, 2022, Geneva, is the United States’ and other European countries’—former colonizers and enslavers—effort to control today's Bandung-like global reparations-centered freedom movement, as evidenced by the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action (DDPA). The Forum, as presently constituted, is a mechanism designed to waylay, blunt and bury the DDPA with hand-picked gatekeepers and the racist slur of “anti-semitism.”

In Durban, South Africa, the world—meaning governments and civil society—reached a consensus and issued the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action (DDPA). The world declared colonialism, slavery, apartheid, and genocide crimes against humanity, without statute of limitations and [with] a basis for reparations.

In 2001, the United States, led by then-Secretary of State Colin Powell, walked out of the Durban World Conference Against Racism. The U.S. and other European countries—former colonizers—worked to prevent the global consensus that was reached and, having failed, continue to work to undermine and bury it.

AWB: Who are the main players in the Permanent Forum?

EN: The Forum is composed of 10 members; five nominated by states and five by the president of the Human Rights Council, “in consultation with civil society.” Here, “civil society” is not limited to people of African descent, as is the case with the members of the [United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues].

While the U.S. described how it pressured governments to vote for its pick, Justin Hanford, little or nothing else is known about the rest's appointment. It is located in Geneva, in the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), instead of the more accessible New York, under the more appropriate Economic and Social Council.

The chair, Epsy Campbell-Barr, is a former vice president of Costa Rica, one of the world's smallest countries and [containing] an even smaller number of people of African descent; little more than 400,000. The vice chair is Alice Ange'le Nkom of Cameroon. She is the first woman admitted to practice law in Cameroon and is president of the Cameroonian Association for Defence of Homosexuality, co-chairperson of the Central Africa Human Rights Defenders Network, and a member of the National Democratic Institute International Working Group. The rapporteur [an independent human rights expert whose expertise is called upon by the United Nations to report or advise on human rights from a thematic or country-specific perspective] is Michael McEachrane, of Sweden, who calls himself a “mixed race, academic and activist.” As of 2016, there were 110,758 citizens of African nations residing in Sweden.

Justin Hansford, U.S. member/Pan-Euro representative is director of the Howard University Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center. He, like Clarence Thomas, enjoys the good will that comes from the use of Thurgood Marshall's name. Hansford, presenting himself as a Black “liberator,” dismissed the DDPA saying, “I was 16 years old when it was written.” He reportedly “believes he can get a better deal;” apparently under the ruse of “Sustainable Development Goals.”

AWB: What were your contributions to the convening?

EN: I publicly reprimanded Justin Hansford for trying to gaslight me and others when the chair attempted to refuse to take floor responses to McEachrane's attempt to limit DDPA relevance in his “interim” summary of the Forum's future work. “The DDPA will be applied to the extent it applies to people of African descent,” he said. His opening statement is attached.

I challenged Forum participants—in-person and virtually,—to read the DDPA. Admonished them to not let fancy, obscure language, lack of information, age, experience, and a short-term promise (Sustainable Development Goals [SDG]) of an immediate bowl of porridge cause us to betray our peoples. All were challenged to fully claim, affirm, and assert the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action as our human right of self-determination.

I reminded them, “The Durban Declaration and Programme of Action is the heart and soul of this Forum, without the DDPA this is nothing more than a free trip and a talk fest. The Durban Declaration and Programme of Action is our lifeline and that of generations unborn. HOLD ON TO IT—BLACK POWER! BLACK IS BEAUTIFUL! BLACK POWER! BLACK POWER to BLACK PEOPLE!!! ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE!!!” The crowd roared and gave two standing ovations. Black Power and the call for fidelity to the DDPA rang out throughout the remaining days.

AWB: Thank you for your insights and analysis!

https://www.blackagendareport.com/afric ... ulletin-44

*****************

France recalls ambassador and will withdraw military forces from Burkina Faso

By Joseph Ataman, CNN and Reuters

Published 6:35 AM EST, Thu January 26, 2023

A soldier of the French Army patrols a rural area during the Barkhane operation in northern Burkina Faso on November 9, 2019.

Michele Cattani/AFP/Getty Images/FILE CNN

—

Following a formal request from the Burkina Faso government to do so, the French military mission will end a month after receipt of that written demand, the ministry said.

Since 2018, the French and Burkina Faso governments have had an agreement allowing the presence of French troops on Burkinabe soil. French troops have been deployed in West Africa since 2013 to fight jihadist groups in the Sahel.

This withdrawal is the latest step back for France’s military footprint in the Sahel region, after the 2022 withdrawal of French forces from Mali following a military coup in the country and the eventual breakdown in relations with the Malian government.

People hold a sign as they gather to show their support to Burkina Faso's new military leader Ibrahim Traore and demand the departure of the French ambassador at the Place de la Nation in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso January 20, 2023. The sign reads : "France's army get out from our country". REUTERS/Vincent Bado

Burkina Faso's military government demands French troops leave the country within one month

The French Armed Forces declined to comment on the composition of the mission in Burkina Faso, adding that it also did not have a comment on how the withdrawal will affect French operations in the Sahel region.

The French foreign ministry said on Thursday it was recalling its ambassador to Burkina Faso, citing “the context of recent developments”, a day after Paris announced it would withdraw its troops from the African country.

“We have decided to recall our ambassador in Paris, to conduct consultations on the state and perspectives of our bilateral cooperation”, the ministry said in a statement.

Protests by opponents of the French military presence have surged in Burkina, partly linked to perceptions that France has not done enough to tackle an Islamist insurgency that has spread in recent years from neighboring Mali.

https://us.cnn.com/2023/01/26/africa/fr ... index.html

****************

Who is responsible for Ghana’s debt crisis?

Ghana has approached the G20 to restructure its external debts, the majority of which are held by private lenders. The process is necessary to unlock a $3 billion IMF bailout that will see severe austerity measures imposed on the Ghanaian people

January 24, 2023 by Tanupriya Singh

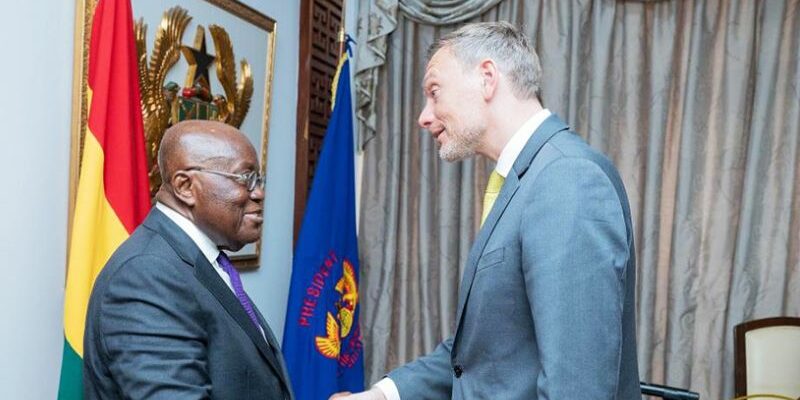

IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva meets with Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo (Photo: @KGeorgieva/Twitter)

On Wednesday, January 18, 26 civil society and aid organizations penned an open letter calling on international creditors to cancel Ghana’s debt. Ghana’s public debt stood at over 467 billion cedis ($46.7 billion) by the end of September, 2022, of which 42% was domestic debt. In December, Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta announced that interest payments on debt were taking up between 70 to 100% of the government’s revenue, and that the ratio of the country’s public debt to its GDP had exceeded 100%.

Based on the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics, 64% of Ghana’s scheduled foreign currency external debt service, which includes principal and interest amounts, between 2023 and 2029 is to private lenders. 20% of the debt is to multilateral institutions and 6% to other governments. Notably, while mainstream reporting on Ghana’s debt scenario tends to emphasize China as the country’s “biggest bilateral creditor,” only 10% of Accra’s external debt service is owed to Beijing.

Approximately $13 billion of Ghana’s external debt is held in the form of Eurobonds by major asset management corporations including BlackRock, Abrdn, and Amundi (UK) Limited. “Ghana’s lenders, particularly private lenders, lent at high-interest rates because of the supposed risk of lending to Ghana,” the open letter read.

“The interest rate on Ghana’s Eurobonds is between 7% and 11%. That risk has materialized… Given that they lent seeking high returns, it is only right that following these economic shocks, private lenders willingly accept losses and swiftly agree to significant debt cancellation for Ghana.”

A weak debt relief infrastructure

In early December, the government announced a domestic debt exchange program under which existing bonds would be exchanged for new ones with a longer period of maturity.

On December 19, the Ghanaian Finance Ministry announced that it was suspending debt service payments on the majority of its external debt, including commercial and bilateral loans. The country was expected to default on the first such payment, a $41 million interest payment due on a $1 billion Eurobond, on January 18.

On January 16, the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, confirmed that Ghana was seeking to restructure its debt under the Common Framework initiative of the G20 countries, becoming the fourth country to do so following Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia.

The Common Framework was one of two debt treatment schemes announced by the G20 in 2020, the first being the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), under which debt payments were to be temporarily suspended, giving poor countries space to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Speaking to Peoples Dispatch, Tim Jones, the head of policy at Debt Justice, explained: “At the start, the DSSI was meant to lead to a suspension of debt to government lenders, to private lenders, and also determine how to do the same for multilateral institutions. However, multilateral institutions and private lenders both refused to take part.”

“So in the end only government lenders suspended payments, which meant that only 23% of debt payments were actually suspended for countries which had applied for the scheme. However, even if the scheme had worked as intended, the problem was that it was just a debt suspension, with the debts still due to be paid years later.”

While the DSSI ended in 2021 with very limited success, the Common Framework had the opportunity to provide a broader debt cancellation, involving private creditors alongside bilateral lenders in the process to ensure that countries’ debts became sustainable.

“But very little was done to outline the details of how that would work. While the G20 stated that government and private lenders would be included in the scheme, however, multilateral lenders were excluded,” Jones said.

“They did not give any new mechanisms to countries to negotiate a reduction in their debt owed to private creditors, leaving it to the debtor governments to say ‘If you want debt cancellation from governments, you have to negotiate the same deal from private creditors.’ But they did not offer any tools to help indebted countries to do that.”

Chad became the first country to reach an agreement under the Common Framework in November 2022, after the process had been delayed and blocked for nearly two years by Swiss commodity trading and mining company Glencore, which held nearly the entirety of Chad’s debt to private creditors, itself comprising one-third of the country’s external debt.

Even after the delays, the agreement did not yield any meaningful debt relief for Chad, merely a postponement of payments.

On January 19, an official from the Paris Club told Reuters that all members of the G20 were in favor of restructuring Ghana’s debt, and that members of the Paris Club were ready to take the initial steps towards forming a creditor committee.

It is possible that Ghana might enter these debt negotiations with a relatively strong position compared to Chad, given that, similar to Zambia, it has suspended its debt payments.

Advocacy groups have demanded that the G20 guarantee that Ghana will be “politically and financially supported to remain in default on any creditor which does not accept the necessary restructuring.” Importantly, they have highlighted that Ghana’s foreign currency bonds are governed by English law, which means that the UK parliament can take the necessary steps to provide legal safeguards for Ghana and rein in private lenders.

As this process plays out at the international level, the necessity of debt cancellation for Ghana is underscored by the fact that living conditions for millions of people in the country have steadily worsened.

Ghana goes to the IMF… again

By December 2022, Ghana’s consumer inflation had soared to 54.1%, the highest in over 20 years. According to figures published by the country’s statistics office on January 11, the prices of housing, electricity, water, and gas and other fuels rose by 82.3% year-on-year by the end of last year.

Meanwhile, the cedi, which had lost 54.2% of its value against the US dollar by November, was termed the year’s “worst performing currency.” These conditions sparked repeated protests in 2022, alongside trade unions struggles against a drastic decline in wages in real value terms.

In an interview with Peoples Dispatch, Kwesi Pratt Junior, the general secretary of the Socialist Movement of Ghana (SMG), said, “Why is Ghana’s economy in such dire straits? For one, while Ghana is heavily endowed with natural resources such as gold [being the 6th largest producer in the world], these resources are not owned by our people or exploited for our benefit.”

“The other part of the problem is that the US dollar has become the currency of preference in international trade. The US owns the dollar, its debt is in dollars, so all it has to do is reprint more dollars. Our [Ghana’s] debt is in dollars too, how are we supposed to pay?”

In July 2022, the government announced that it would approach the IMF for a bailout, in what would be Ghana’s 18th arrangement with the institution, in a stark departure from its earlier vocal opposition to seeking assistance from the IMF.

Also read: Ghana’s unions and left reject bailout talks with the IMF as economic crisis spirals

On December 12, the IMF announced that a staff-level agreement had been reached with Ghana’s government for a three-year, $3 billion dollar arrangement under an Extended Credit Facility (ECF).

“The Ghanaian authorities have committed to a wide-ranging economic reform program,” the Fund said in a statement, adding that the “fiscal strategy relies on front loaded measures to increase domestic resource mobilization and streamline expenditure…”

Such language of “structural reforms” is indicative of one thing—more austerity, similar to Ghana’s previous engagements with the IMF and their disastrous impacts, and the signs of which are already visible in the country’s 2023 national budget.

By the second quarter of 2022, Ghana’s unemployment rate stood at 13.9%. In a country where the civil service is the largest employer, the government has now implemented a hiring freeze in the public sector. Tax measures including a 2.5% increase in the Value Added Tax (VAT) rate, which disproportionately impacts poor people, have been announced.

The government has also imposed a “cap on salary adjustment of State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) to be lower than negotiated base pay increase.” While the government and trade unions have reached an agreement to increase the salaries of all public servants by 30% in 2023, the increase will still not meet the rate of inflation.

The Ghana Trades Union Congress has also accused the government of defaulting on its contributions to the pension schemes of over 600,000 public sector workers since February 2022.

These anti-poor austerity measures are being implemented in pursuit of an IMF loan that is still pending approval—which is in turn conditional on the restructuring of Ghana’s debts to a level deemed sustainable.

Watch: Kwesi Pratt Jr.: Nobody believes IMF deal will solve Ghana’s crisis

“The IMF is unfortunately central to how debt is managed in the global system. In theory, there is no structured process of dealing with a government debt crisis, there is no way for governments to declare bankruptcy,” Jones said.

“So the IMF rules the system that exists in its place. When countries get into a debt crisis they turn to the Fund to seek more loans, and often the IMF grants these loans, which enables previous creditors to keep being paid while the IMF insists on austerity.”

The Fund determines the contours of debt relief—how much debt can be restructured, what does this restructuring look like, whether it is in the form of simply moving payments into the future or actual debt cancellation—in a package, Jones added, which also includes deciding the extent of austerity.

Rescuing Ghana from the imperialist debt trap

Ghana’s debt crisis has been attributed to a continued dependence on commodity exports—rooted in colonialism—which are susceptible to volatile prices, as well as irresponsible lending and borrowing practices. The present debt crisis also shares key similarities with the debt crisis that had affected much of the Global South in the 1980s and 1990s.

“The decade following the 2008 financial crisis saw a big increase in lending, the biggest driver of which are high interest loans from private lenders,” Jones stated. “A similar boom in lending had taken place in the 1970s. At the start of the 1980s, there were a series of economic shocks, commodity prices fell and interest rates went up. Even then much of the debt was owed to private lenders.”

However, in the 1980s and 1990s, the IMF and the World Bank lent more money, which allowed private lenders to keep being paid. As a result, “there was a transfer of debt from private lenders to multilateral institutions. This proved disastrous for countries who had to pay back these loans whilst implementing austerity.”

When some debt cancellation did take place in the 2000s, it was the multilateral creditors who were affected, and had to pay, instead of the original lenders. “This incentivized these lenders to keep acting recklessly, and is one of the reasons we have another crisis now.”

Ghana’s debt fell significantly between 2003 and 2006 following debt cancellation under the IMF and World Bank’s Heavily Indebted Poor Countries and Multilateral Debt Relief initiatives. Ghana witnessed major economic growth in the following years as the prices of gold and cocoa, two of the country’s main exports, began to increase. This also led to a rise in lending—between 2007 and 2015, Ghana had $18.2 billion in external loans and $8.7 billion in debt payments.

Between May 2007 and February 2015, the IMF and the World Bank assessed Ghana to be at moderate risk of debt distress. This classification meant that Ghana was eligible to receive 50% of the support from the World Bank in the form of grants and the other 50% as loans. However, analysis has revealed that 93% of the Bank’s funding to Ghana during this time was in the form of loans.

In March 2015, Ghana was declared to be at high risk of debt distress, qualifying the country to access 100% of the support in the form of grants. However, the World Bank still agreed to give the country $1.16 billion in loans.

Between 2013 and 2014, commodity prices fell, as did the value of the cedi. As a result, the relative size of Ghana’s external debt and debt payments increased. The government was forced to take on new debts in the form of bonds in 2013, 2014, and 2015, all with high interest rates ranging from 7.9% to 10.75%.

The crisis was taking the shape of a new debt trap. Speculators now stand to rake in massive profits unless there is substantial debt cancellation for Ghana.

In 1987, the president of Burkina Faso and Marxist Pan-Africanist revolutionary, Thomas Sankara, had raised a rallying call for a “united front against debt”—“debt is neo-colonialism,” he had stressed, “controlled and dominated by imperialism, debt is a skillfully managed reconquest of Africa.”

35 years later, Sankara’s words still ring true, as Western private lenders continue to reap obscene profits off the very debt that is pushing people in countries such as Ghana further into poverty.

“These debts are simply unpayable not just because of the unfair international economic order. They are also unpayable because a lot of these loans serve the foreign policy interests of imperialist powers,” Kwesi Pratt Junior told Peoples Dispatch.

“The best example of this is Zaire (present day DRC) under Mobuto Sese Seko. Everybody knew that he was richer than his country, they knew that the loans that were being given to Zaire could not be repaid and yet they kept pumping in loans, because they wanted to hold up Zaire as a bastion against the expansion of communism.”

Pratt further added, “we are in the current condition because our economy is still modeled on colonialism. One of the best ways to understand this is to look at Ghana’s railway network—it always starts from areas of wealth, the mining areas of bauxite, gold, and diamonds, and ends up at the ports. These minerals do not move towards the centers of production, the factories, but they go to the ports to be exported out of the country.”

“This typifies the relationship between Ghana and the colonial metropolis,” he emphasized. “What does it mean when Ghana signs a foreign exchange retention agreement with mining companies allowing them to keep 98% of the total value of minerals exported from the country. In actuality, only about 2% of the value of what is mined in Ghana comes back to its economy. This has to change.”

For the SMG, the way out, not just for Ghana but for all of Africa, is through a fundamental restructuring of the economy and a return to the agenda of the independence movement—for the people to be able to determine their own political destiny and to own and use their natural resources for their own benefit.

“We need to build an economy that responds directly to the needs of the people, to restructure it in a way that will make land available to the tillers, and that will ensure that people have access to services such as healthcare and education,” Pratt added.

https://peoplesdispatch.org/2023/01/24/ ... bt-crisis/