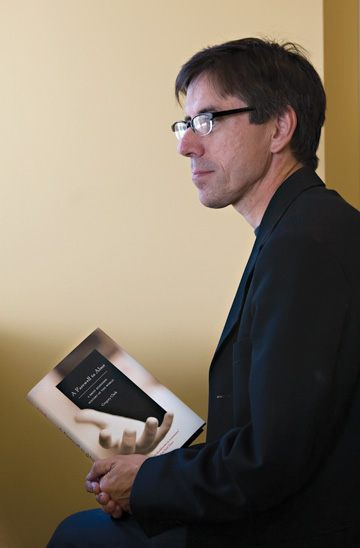

Came across this odious pustule yesterday while browsing the public library and thought I must share.

Why are some parts of the world so rich and others so poor? Why did the Industrial Revolution--and the unprecedented economic growth that came with it--occur in eighteenth-century England, and not at some other time, or in some other place? Why didn't industrialization make the whole world rich--and why did it make large parts of the world even poorer? In A Farewell to Alms, Gregory Clark tackles these profound questions and suggests a new and provocative way in which culture--not exploitation, geography, or resources--explains the wealth, and the poverty, of nations.

Countering the prevailing theory that the Industrial Revolution was sparked by the sudden development of stable political, legal, and economic institutions in seventeenth-century Europe, Clark shows that such institutions existed long before industrialization. He argues instead that these institutions gradually led to deep cultural changes by encouraging people to abandon hunter-gatherer instincts-violence, impatience, and economy of effort-and adopt economic habits-hard work, rationality, and education.

The problem, Clark says, is that only societies that have long histories of settlement and security seem to develop the cultural characteristics and effective workforces that enable economic growth. For the many societies that have not enjoyed long periods of stability, industrialization has not been a blessing. Clark also dissects the notion, championed by Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs, and Steel, that natural endowments such as geography account for differences in the wealth of nations.

From the Inside Flap

"What caused the Industrial Revolution? Gregory Clark has a brilliant and fascinating explanation for this event which permanently changed the life of humankind after 100,000 years of stagnation."--George Akerlof, Nobel Laureate in Economics and Koshland Professor of Economics, University of California, Berkeley

"This is a very important book. Gregory Clark argues that the Industrial Revolution was the gradual but inevitable result of a kind of natural selection during the harsh struggle for existence in the pre-industrial era, in which economically successful families were also more reproductively successful. They transmitted to their descendants, culturally and perhaps genetically, such productive attitudes as foresight, thrift, and devotion to hard work. This audacious thesis, which dismisses rival explanations in terms of prior ideological, technological, or institutional revolutions, will be debated by historians for many years to come."--Paul Seabright, author of The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life

"Challenging the prevailing wisdom that institutions explain why some societies become rich, Gregory Clark's "A Farewell to Alms" will appeal to a broad audience. I can think of nothing else like it."--Philip T. Hoffman, author of Growth in a Traditional Society

"You may not always agree with Gregory Clark, but he will capture your attention, make you think, and make you reconsider. He is a provocative and imaginative scholar and a true original. As an economic historian, he engages with economists in general; as an economist, he is parsimonious with high-tech algebra and unnecessarily complex models. Occam would approve."--Cormac Ó Gráda, author of Jewish Ireland in the Age of Joyce

"This should rapidly become a standard work on the history of economic development. It should start whole industries trying to test, refine, and refute its explanations. And Gregory Clark's views on the economic merits of imperialism and the fact that labor gained the most from industrialization will infuriate all the right people."--Eric L. Jones, author of Cultures Merging and The European Miracle

"While many books on the Industrial Revolution tend to focus narrowly either on the event itself, or on one explanation for it, Gregory Clark does neither. He takes an extremely long-run view, covering significant periods before and after the Industrial Revolution, without getting bogged down in long or detailed exposition. This is an extremely important contribution to the subject."--Clifford Bekar, Lewis and Clark College

Countering the prevailing theory that the Industrial Revolution was sparked by the sudden development of stable political, legal, and economic institutions in seventeenth-century Europe, Clark shows that such institutions existed long before industrialization. He argues instead that these institutions gradually led to deep cultural changes by encouraging people to abandon hunter-gatherer instincts-violence, impatience, and economy of effort-and adopt economic habits-hard work, rationality, and education.

The problem, Clark says, is that only societies that have long histories of settlement and security seem to develop the cultural characteristics and effective workforces that enable economic growth. For the many societies that have not enjoyed long periods of stability, industrialization has not been a blessing. Clark also dissects the notion, championed by Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs, and Steel, that natural endowments such as geography account for differences in the wealth of nations.

From the Inside Flap

"What caused the Industrial Revolution? Gregory Clark has a brilliant and fascinating explanation for this event which permanently changed the life of humankind after 100,000 years of stagnation."--George Akerlof, Nobel Laureate in Economics and Koshland Professor of Economics, University of California, Berkeley

"This is a very important book. Gregory Clark argues that the Industrial Revolution was the gradual but inevitable result of a kind of natural selection during the harsh struggle for existence in the pre-industrial era, in which economically successful families were also more reproductively successful. They transmitted to their descendants, culturally and perhaps genetically, such productive attitudes as foresight, thrift, and devotion to hard work. This audacious thesis, which dismisses rival explanations in terms of prior ideological, technological, or institutional revolutions, will be debated by historians for many years to come."--Paul Seabright, author of The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life

"Challenging the prevailing wisdom that institutions explain why some societies become rich, Gregory Clark's "A Farewell to Alms" will appeal to a broad audience. I can think of nothing else like it."--Philip T. Hoffman, author of Growth in a Traditional Society

"You may not always agree with Gregory Clark, but he will capture your attention, make you think, and make you reconsider. He is a provocative and imaginative scholar and a true original. As an economic historian, he engages with economists in general; as an economist, he is parsimonious with high-tech algebra and unnecessarily complex models. Occam would approve."--Cormac Ó Gráda, author of Jewish Ireland in the Age of Joyce

"This should rapidly become a standard work on the history of economic development. It should start whole industries trying to test, refine, and refute its explanations. And Gregory Clark's views on the economic merits of imperialism and the fact that labor gained the most from industrialization will infuriate all the right people."--Eric L. Jones, author of Cultures Merging and The European Miracle

"While many books on the Industrial Revolution tend to focus narrowly either on the event itself, or on one explanation for it, Gregory Clark does neither. He takes an extremely long-run view, covering significant periods before and after the Industrial Revolution, without getting bogged down in long or detailed exposition. This is an extremely important contribution to the subject."--Clifford Bekar, Lewis and Clark College

Genetically Capitalist? The Malthusian

Era, Institutions and the Formation

of Modern Preferences.

3 March 2007

Before 1800 all societies, including England, were Malthusian.

The average man or woman had 2 surviving children. Such

societies were also Darwinian. Some reproductively successful

groups produced more than 2 surviving children, increasing their

share of the population, while other groups produced less, so that

their share declined. But unusually in England, this selection for

men was based on economic success from at least 1250, not

success in violence as in some other pre-industrial societies. The

richest male testators left twice as many children as the poorest.

Consequently the modern population of the English is largely

descended from the economic upper classes of the middle ages.

At the same time, from 1150 to 1800 in England there are clear

signs of changes in average economic preferences towards more

“capitalist” attitudes. The highly capitalistic nature of English

society by 1800 – individualism, low time preference rates, long

work hours, high levels of human capital – may thus stem from

the nature of the Darwinian struggle in a very stable agrarian

society in the long run up to the Industrial Revolution. The

triumph of capitalism in the modern world thus may lie as much

in our genes as in ideology or rationality.

Gregory Clark

University of California, Davis, CA 95616

Era, Institutions and the Formation

of Modern Preferences.

3 March 2007

Before 1800 all societies, including England, were Malthusian.

The average man or woman had 2 surviving children. Such

societies were also Darwinian. Some reproductively successful

groups produced more than 2 surviving children, increasing their

share of the population, while other groups produced less, so that

their share declined. But unusually in England, this selection for

men was based on economic success from at least 1250, not

success in violence as in some other pre-industrial societies. The

richest male testators left twice as many children as the poorest.

Consequently the modern population of the English is largely

descended from the economic upper classes of the middle ages.

At the same time, from 1150 to 1800 in England there are clear

signs of changes in average economic preferences towards more

“capitalist” attitudes. The highly capitalistic nature of English

society by 1800 – individualism, low time preference rates, long

work hours, high levels of human capital – may thus stem from

the nature of the Darwinian struggle in a very stable agrarian

society in the long run up to the Industrial Revolution. The

triumph of capitalism in the modern world thus may lie as much

in our genes as in ideology or rationality.

Gregory Clark

University of California, Davis, CA 95616

Section Widget

Section Widget