NicaNotes: Stop US Aggression against Venezuela! / ¡Alto a la Agresión Estadounidense contra Venezuela!

October 23, 2025

NicaNotes

October 23, 2025

New Webinar on Oct. 26th!

Discover how Nicaragua saves lives before, during and after disasters and how nationwide drills train more than a million citizens.

Register for Nica Webinar: bit.ly/NicaOct26

Stop US Aggression against Venezuela! / ¡Alto a la Agresión Estadounidense contra Venezuela!

[The Nicaragua Solidarity Coalition—of which the Nicaragua Network/Alliance for Global Justice is a member—has released an important statement on Venezuela. You can also find it in both Spanish and English here.]

The Nicaragua Solidarity Coalition demands an end to US aggression against Venezuela, which is on the brink of outright war. Any escalation in the violence against Venezuela will cause more suffering and deaths in the South American country, destabilize the region, and endanger all countries seeking a path independent from US domination, especially Cuba and Nicaragua.

A sousaphone player at the No Kings rally in Tucson proclaims “No War on Venezuela!” Photo: Tanya Nuñez

US actions indicate a strike on Venezuela is imminent:

After the Trump administration designated international drug-trafficking groups as “foreign terrorist organizations” (FTOs), without any evidence, it accused Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro of being their ringleader. By July, a “secret directive” authorized military operations against FTOs at sea and on foreign soil.

In August, the administration raised its illegal “bounty” on President Maduro to US$50 million and launched a massive naval deployment off the coast of Venezuela, which includes nuclear capable submarines and jets and quickly grew to 10,000 troops.

On September 2, the US blew up the first of four or five alleged “drug” boats in international waters off of Venezuela, committing extrajudicial executions.

By mid-September, the Pentagon notified Congress under the War Powers Resolution that US forces were engaged in a “non-international armed conflict” with drug cartels.

On October 1, the Defense/War Department issued a “confidential memo” and told Congress that the US was engaged in armed conflict.

On October 6, Trump ended back-channel diplomatic contacts with Venezuela, which had been essential since the rupture of diplomatic relations in 2019. That same day, Venezuela informed the US of a thwarted plan by Venezuelan right-wing extremists to plant explosives at the US embassy in an attempted false-flag operation.

On October 10, Maria Corina Machado—a US-paid, violent, Zionist, extreme right-wing Venezuelan political opposition figure—received the Nobel Prize after being endorsed by Secretary Marco Rubio, in a clear a maneuver to manufacture consent for regime change in Venezuela.

We must not be fooled by this perversion of the peace prize or the countless unfounded accusations against Venezuela and its democratically elected president. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, and even the DEA, report that Venezuela is not a drug trafficking country, nor are Cuba or Nicaragua. Like its lies about migrants, the Trump administration has fabricated the “threat” posed by Venezuela. The real reason the administration is pushing for war against Venezuela is to regain control of its vast resources—including the world’s largest oil reserves.

We demand an end to US impunity and the withdrawal of US troops and war materiel from the Caribbean before the situation escalates any further. We vehemently object to the deployment of nuclear capable vessels in a region which, in response to the Cuban Missile Crisis, declared itself a nuclear-free zone in 1967, and which the US committed itself to respect in 1971. We demand respect for international law and the sovereignty of nations. The people of Venezuela and the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean must be allowed to live in peace with the form of government they have chosen.

Hands Off Venezuela! Venezuela is Hope! Venezuela is not a threat!

US Hands Off Latin America and the Caribbean!

ADDENDUM: Since this statement was issued, Venezuela Analysis reported that, on Oct. 15, the Trump administration authorized the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to carry out lethal covert operations in Venezuela. The US military also struck another boat in the Caribbean. A couple of days later, news reports described a US attack on a submersible that killed two more and had two survivors who were repatriated to Ecuador and Colombia. With at least two subsequent attacks, the Guardian has the total at 34 killed as of Oct. 22nd but its figures are confusing!

Please take this urgent action from the Alliance for Global Justice to STOP THE WAR on Venezuela:

There is a bipartisan effort to force a vote in the Senate that would require Congressional approval for military action against Venezuela. We urge people to send an email to their Senators as well as to call, visit, and demonstrate at Senate offices to demand NO WAR with Venezuela! Click below to send an email!

Demand that your Senators vote NO WAR with Venezuela!

Briefs

By Nan McCurdy

2026 Budget Guarantees Social Welfare and Development

The Sandinista government has allocated 65.4 percent of projected revenues in next year’s budget to programs and actions aimed at combating poverty. This represents US$2.99 billion, said Óscar Mojica, Minister of Finance and Public Credit. The bill establishes social and economic priorities, including public investment, social spending, strengthening the production chain, care for children and adolescents, gender policies, development of the Caribbean Coast, and citizen protection and security, among others. Mojica presented the 2026 General Budget bill to the National Assembly, which amounts to US$5.36 billion.

Social investment and the transportation sector account for 70.8 percent of the total budget. According to the official, revenues are projected to be in the order of US$4.7 billion. Of the total amount allocated to social investment, the largest share went to the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure and the Ministry of Education. This reaffirms Nicaragua’s commitment to the well-being of families and the social development of the country. (La Primerisima, 21 October, 2025)

State-of-the-Art Soccer Stadium Now Complete

Authorities announced that construction of the new Miguel “Chocorrón” Buitrago Soccer Stadium has been fully completed. The sports field was built to all the quality standards established by FIFA and its regional affiliate CONCACAF with the aim of hosting national and international children’s and youth tournaments. The stadium has seating capacity for 2,000 spectators, a FIFA PRO-certified artificial turf field, dressing rooms with bathrooms for players, changing rooms for referees, bleachers, boxes, a media booth area, and public restrooms. It also has cafeterias, artificial lighting, a professional sound system, areas for convenience stores, and ample parking for the public. See photos:

https://radiolaprimerisima.com/nuevo-es ... acionales/ (La Primerisima, 16 October 2025)

Sandinista Government to Give Vouchers to 63,000 High School Graduates

The Ministry of Education will give 63,000 vouchers to students graduating from high school in public schools throughout the country. The bonuses will be handed out by the presidents of the Federation of Secondary School Students (FES) and the municipal coordinators of the local 19 de Julio Sandinista Youth Organization during celebrations in all schools from November 24 to 27 in recognition of the efforts of each student preparing to enter universities and technical schools. The delivery of this grant reaffirms the will of the Sandinista government to bring improvements for Nicaraguan families. (La Primerisima, 16 October 2025)

Sandinista Government Sends Special Greetings to British Solidarity

On Oct. 18, the Government of Reconciliation and National Unity delivered a special greeting at the Annual Meeting of the Nicaragua Solidarity Campaign Action Group (NSCAG) in London. The message was delivered by the Co-Minister of the Exterior, Valdrak Jaentschke. Here are some excerpts from the message:

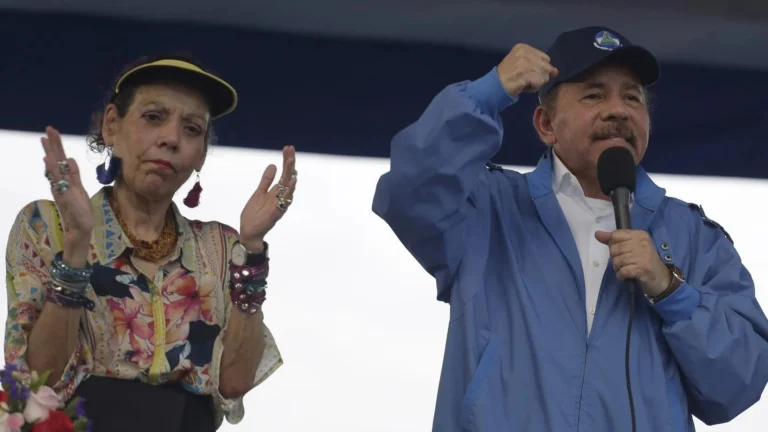

“It is a special honor for me to address you at this Annual General Assembly and to convey the Fraternal Embrace, as Revolutionary Sisters and Brothers, from our Co-Presidents Comandante Daniel Ortega Saavedra and Compañera Rosario Murillo Zambrana.… We want to express our gratitude for the solidarity, the affection and the constant work you have done for so many years to inform, clarify and defend the Sandinista Popular Revolution. You have remained firm and tireless, walking alongside the Nicaraguan People and the revolutions and progressive forces around the world, despite the systematic media campaigns to discredit our popular and anti-imperialist process, attempting to minimize the enormous and significant advances the Revolution has made in favor of the humble, working people of Nicaragua.

“Nicaragua demonstrated that a Popular Revolution is capable of improving the lives of its People by fostering development, restoring the rights that were taken away by the empire, the oligarchy and its neoliberal model, while remaining firm and loyal to the Sandinista Revolutionary political thinking from which it emerged. The fight against poverty is the central element of the National Human Development Plan, our Plan to Fight Poverty, which firmly upholds free health care and education as fundamental rights; access to basic services such as water, electricity, roads, hospitals, clinics and schools that reach rural communities, uniting the country. The country’s production and income increased year after year, while the rights of women, youth, workers, Indigenous and Afro-descendant Peoples, and the entire Nicaraguan People prospered under the leadership of the Sandinista Front….

“At this meeting, we remember, celebrate and express our gratitude for your firmness, perseverance and permanence on the side of the Popular Movement, on the side of the Sandinista Popular Revolution.

“With much love. With much gratitude. We continue building the Revolution. October 18, 2025. To see the entire message in English or Spanish:

https://www.el19digital.com/articulos/v ... -nicaragua To see you tube video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GM7lT7ipIDU&t=61s (El 19 Digital, 18 October 2025)

Evangelicals in Dominican Republic say Nicaragua Promotes Peace

On October 18, the Eleventh Congress on the Family and the Culture of Peace was held in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, organized by the Dominican organization Equity and Social Justice Foundation. Leaders from various evangelical churches gathered at the event in the Dominican Republic and highlighted Nicaragua as a country that promotes peace. Representatives from Nicaragua explained their country’s model of participation, faith, family and community. Pastor Feliciano Lacen, president of the Dominican Council of Evangelical Unity (CODUE), and Reverend Fidel Lorenzo, president of the Equity and Social Justice Foundation, highlighted the progress made in Nicaragua in terms of a culture of peace, noting that as a country that practices the solidarity taught by Christ, it is a model to be followed in the region. The event was attended by some 150 Dominican families, who applauded Nicaragua’s participation in the congress. (La Primerisima, 18 October 2025)

Fifth Gold Medal for Nicaragua in Central American Games

Candelaria Resano was crowned Central American champion in women’s shortboard surfing at the Central American Games in Guatemala. Shortboard surfboards are high-performance boards that generate maximum speed, grip, and maneuverability. They are reserved for experienced surfers and for waves of respectable size and power. See photos:

https://radiolaprimerisima.com/quinta-m ... mericanos/ (La Primerisima, 21 October 2025)

https://afgj.org/nicanotes-stop-us-aggr ... -venezuela

*****

Nicaraguan GDP To Expand In 2026

Nicaraguan currency. Photo: Canal 4.

October 23, 2025 Hour: 9:28 am

The Central Bank expects the exchange rate of the cordoba against the dollar to remain unchanged next year.

On Wednesday, Nicaraguan Central Bank President Ovidio Reyes anounced that his country’s economy will grow 4% in 2026, with an annual inflation range between 2% and 2.5%. Whilst for 2025, the expected growth of gross domestic product (GDP) remains between 3% and 4%.

Reyes noted that next year will be an extension of 2025 as economic growth will also be around 4%, and inflation could be slightly lower depending on global developments. He noted that the first half of 2025 showed a “dynamic” economy, with high demand in supply sectors and growth in most productive ones.

In the first semester, the fastest-growing activities were construction (10%), trade (8.3%), hotels and restaurants (7%), and financial intermediation (4.9%).

Concerning exports, Reyes underlined that Nicaragua has rebounded this year, “growing in both volume and level”, with exports expected to reach around US$8 billion by the end of 2025, which is a new record.

The text reads, “The 2026 budget prioritizes the fight against poverty and the well-being of the Nicaraguan people. The Government of Reconciliation and National Unity reaffirms its commitment to human development and social justice, allocating 65% of the 2026 General Budget of the Republic.”

Nicaraguan GDP increased by 3.9% in the first half of the year, exporting a total of US$3,9 billion in goods, 13.2% more than the same period in 2024, mainly due to the 8.8% increase in international prices.

In this sense, the Central Bank announced that the cordoba’s slide rate against the U.S. dollar will be 0% in 2026, meaning an official exchange rate of 36.6243 cordobas per dollar, supported by economic stability and low inflation.

Furthermore, domestic conditions have consolidated the stability of the financial system, highlighting the performance of lending activity, leveraged by the growth of public deposits, and showing improvements in profitability.

https://www.telesurenglish.net/nicaragu ... d-in-2026/

*****

Sandinismo, Class Dictatorship, and the Siege of a Revolution

Posted by Internationalist 360° on October 21, 2025

Prince Kapone

When the workers, peasants, and poor take state power and refuse to give it back, the oligarchy calls it tyranny and the empire calls it a crisis. We call it democracy from below.

The State Is a Hammer, Not a Halo

The liberals and their academic chaperones treat the state like a church—something holy, something to be judged by its hymns and not its history. They speak of “democracy” and “authoritarianism” as if these words float in the clouds, untouched by plantations, monopolies, or foreign banks. But anyone trained by struggle—and not by think tanks—knows the truth: the state is not a moral sanctuary. It is a weapon. Lenin reminded us that the state is “a special organization of force,” and force is never neutral. It answers to a class. It serves a camp. It bends its knee to one set of interests or another, but never to all. The question is not whether Nicaragua is democratic in the eyes of the New York Times or the European Parliament. The question is: whose hands are on the hammer, and whose skulls was it built to crack?

A Marxist cannot be confused here. There is no such thing as a state “for everyone.” There is no political system above class, above property, or above empire. If the ruling class owns the land, owns the banks, owns the press, and owns the guns, then it will also own the constitutional poetry that explains why this arrangement is “freedom.” Bourgeois democracy is simply the dictatorship of capital with better public relations. You get to choose the color of your chains, not whether you wear them. And when the oppressed dare to fight for power, suddenly the same ruling class that funded death squads from Guatemala to Angola begins weeping over “human rights.” Spare us the melodrama. We have seen this movie before. Every anti-colonial project that refuses to kneel is labeled a tyranny. Every revolution that arms the poor is condemned as a crime. And every leader who dares defy Washington becomes, overnight, a “strongman.” Funny how the vocabulary of moral outrage always aligns with the foreign policy needs of the State Department.

To understand Nicaragua, then, we start from a simple, unsentimental clarity: the Sandinista state is an instrument of class rule. It exists in a world system built on plunder, in a hemisphere patrolled by empire, and in a country whose oligarchy long treated the nation like a private hacienda. When the FSLN returned to office in 2007, it did not inherit a blank slate. It inherited the scars of a defeated revolution, the wreckage of neoliberal restructuring, and a popular class fragmented but not broken. The task before it was not abstract “good governance.” The task was to rebuild a material base for sovereignty, improve the lives of workers and peasants, and prevent the oligarchs and their Yankee patrons from retaking the machinery of the state. That is what governs Sandinista decision-making—not Instagram libertarian fantasies about “freedom,” not NGO checklists, and not the approval ratings of institutions that cheered the Contra war.

We judge a state by its class commitments, its class enemies, and its class outcomes. Who does it empower? Who does it dispossess? Who rises, who eats, who learns, who heals, who organizes—and who howls in rage when they lose their privileges? That is the only serious measure for anyone who claims the Marxist tradition. Everything else is sentimental décor. And by this measure, Nicaragua stands where it has stood since the first literacy brigades: with the poor, against the oligarchy; with the nation, against the empire; with the popular classes, against the comprador parasites who would rather sell the country than share it.

The Hands That Hold the Hammer

If you want to know who commands a state, don’t study the speeches—study the social forces that can shut down a port, paralyze a city, harvest a nation, or defend a neighborhood. Power is not a metaphor. Power is organized people, disciplined institutions, and class alliances rooted in material life. In Nicaragua, the backbone of that power is not the oligarchic salons of Managua, nor the NGO aristocracy funded from abroad, but the dense architecture of popular-class organization: the unions of the Frente Nacional de los Trabajadores (FNT), the health workers of FETSALUD, the teachers’ cadre of ANDEN, the peasant and small-producer base of UNAG, and the cooperative networks that bind land, labor, and community into a living political force. These are not spectators in the Sandinista process—they are its locomotive, its muscle, and increasingly, its administrators and legislators. Their fingerprints are on ministries, mayoralties, and parliamentary benches not because of charity from above, but because they represent the productive life of the country itself.

Look at the National Assembly and you do not see a parade of bankers, oligarch sons, or free-market technocrats trained by the IMF. You see doctors who once organised hospital floors, teachers who led strikes in the neoliberal era, union negotiators hardened in factory disputes, and community organisers who rose through the structures of the barrios and the countryside. The presidency of the Assembly itself is held by a former union leader from FETSALUD—Gustavo Porras Cortés, a physician and trade-unionist turned legislator. That is a fact which makes the old ruling class seethe, because it violates their preferred social order: the rich should rule, the poor should obey, and the worker should never sit at the head of the table. But history in Nicaragua has not been kind to oligarchic expectations.

The Sandinista bloc is not a rhetorical “people.” It is a material people, organized into sectors that form a coherent political subject. The unions—especially in health, education, energy, and public service—anchor the urban working class and supply a steady stream of cadre into the machinery of the state. In the countryside, cooperatives and small producers align with the process not out of superstition, but because electrification, credit, roads, and technical support have turned survival into possibility. Meanwhile, the women of the popular economy—through mass programs like Usura Cero—have become an indispensable pillar of the social base, transforming what the bourgeoisie once dismissed as the “informal sector” —the majority of Nicaragua’s workforce—into a loyal, mobilized, self-conscious constituency with real stakes in public policy,, strengthened by state programs administered through MEFCCA and initiatives such as Usura Cero. This is what a governing alliance looks like when it grows from the bottom instead of being engineered in embassy hallways.

And it is precisely this architecture that terrifies the oligarchy. Because a mobilized popular bloc is not just a voting base. It is a counter-class with its own institutions, its own leadership pipeline, and its own capacity to govern. It can fill plazas, defend territory, pressure ministries, produce food, and project force. It is a bloc in motion—with memory, discipline, and organization—which means it can win, survive, and rule. The oligarchs do not fear “dictatorship.” They fear dispossession. They fear that the people who sow, teach, heal, and build the country will no longer accept a political order where wealth writes the law and the poor bleed for the balance sheets of a few families. And so they cry “authoritarianism” the way a thief yells “police brutality” when the stolen goods are taken back.

To understand the Sandinista state, you must understand this bloc: workers consolidated through their federations, peasants and cooperatives rooted in land and production, public-sector professionals forged in social struggle, women of the popular economy pulled into political life at scale—all aligned, all organized, all present inside the state itself. This is not the sociology of a neoliberal republic. This is a different kind of class project, built by the very people capitalism had written out of history. And it is from this base, and for this base, that the Sandinista government governs.

The Masters Who Lost the Plantation

Every revolution creates two nations inside one border: the nation of those who gain a future, and the nation of those who lose their throne. In Nicaragua, the oligarchy once ruled like hereditary landlords of a private estate, passing the country between a handful of families, their bankers and business chambers, their bishops, and their friends in Washington. They never believed the workers or peasants were a political subject—only a labor pool to be disciplined, a flock to be preached to, or a market to be emptied. Their “democracy” was the freedom to loot, their “pluralism” was the right to own everything, and their “civil society” was the network of elite business associations and publisher dynasties that reproduced their class worldview. When the popular classes organized themselves into a governing force, the oligarchy did not suddenly discover a love for civil liberties. What they discovered was that history had flipped the script, and they were no longer the authors.

This is why the loudest cries of “dictatorship” come from those who once dictated. The business chambers—especially those aligned through COSEP—did not abandon the Sandinista process because of human rights, transparency, or institutional purity. They abandoned it when the state stopped treating them as the natural managers of national life—when policy shifted and foreign capital’s veto over the direction of the country began to weaken. Their revolt was not moral—it was material. When capital loses command it calls that loss “authoritarianism.”

U.S. imperialism functions here as the external wing of the same class. Washington is not offended by repression; it is offended by sovereignty. The same government that arms dictators from Tegucigalpa to Riyadh dares speak of democracy only when a nation stands up for itself. Through sanctions such as the NICA Act and the RENACER Act, through media warfare and NGO fronts, the United States seeks to restore the old colonial chain of command, where Nicaraguan elites take orders and the popular classes take the blows. They want to turn back the clock to the days when foreign capital planned the economy, USAID planned “civil society,” the clergy planned the morality, and the people planned nothing. U.S. policy documents show this logic plainly. Critical commentary identifies precisely the pattern of imperial coercion at play.

But their social base has shrunk. The oligarchs are not a nation, only a fraction: big agro-exporters rooted in 19th-century landholding patterns, bankers tied to transnational finance and external capital, media barons who treat oligarchy as a natural right, and the professional-managerial layer that depends on imperial tutelage for political relevance. This bloc can manipulate headlines, but it cannot harvest a field, electrify a village, or feed a population. It has money, embassies, and think tanks—but no people. And a class without the people may still sabotage, conspire, and destabilize—but as studies of Nicaragua’s elite make clear, it can no longer govern by consent or by production.

So the struggle in Nicaragua is not an argument between “authoritarianism” and “democracy,” as the imperial press pretends. It is a contest between two class projects: one rooted in land, labor, sovereignty, and mass organization; the other rooted in capital, dependency, and foreign tutelage. One fights to deepen the revolution; the other fights to restore the plantation. Everything else is decoration. To name the enemy clearly is not extremism. It is clarity. And clarity is the first duty of anyone who claims to stand with the oppressed.

The State with Calloused Hands

If the class character of a government is revealed by the people who wield its instruments, then the Sandinista state must be studied not through slogans, but through its cadre. Behind many ministries and senior posts is a social genealogy documented at the 2007 cabinet’s formation. The officials of this process did not graduate from the oligarchic finishing schools of the past; they were forged in teachers’ unions like ANDEN, peasant and cooperative leadership (UNAG/FENACOOP), literacy brigades, neighborhood committees, student fronts, and community struggles that long predate their titles. This is not a state staffed by heirs of coffee barons or by technocrats on loan from the IMF. It is a state built through the recruitment of teachers, health workers who rose into MINSA leadership, agronomists and farm-sector organizers appointed to MAGFOR, cooperative organizers, union militants, and barrio-level cadre whose political formation came from collective struggle, not elite mentorship. The bourgeoisie knows this—and it is why they insist on calling the government illegitimate. What enrages them is not tyranny, but trespassing. The poor have entered rooms once reserved for their betters, and they did not come to dust the furniture.

The National Assembly reflects this reality in living color. When the president of the legislature is a former trade-union doctor like Gustavo Porras Cortés, you are not looking at a country run by bankers and plantation heirs. You are looking at a state where people who once fought for wages, clinics, and classrooms now fight over laws instead of scraps. The official record in the Assembly’s roster and even reporting from unsympathetic observers show a legislature shaped by workers, teachers, health professionals, and grassroots organizers—not the usual wallpaper of CEOs and oligarch sons who write policy with one hand and count profits with the other.

The same is true of the executive ministries. In sectors like health, education, agriculture, family economy, and energy you can find major policy leaps after 2007—such as rural electrification via the Off-grid Rural Electrification (PERZA) Project and the Rural Roads Infrastructure Improvement Project. These ministries are staffed less by corporate technocrats and more by public-sector cadres, resulting in outcomes like roads to forgotten towns and clinics in remote areas. Bureaucracy in Nicaragua is not an aristocracy but in many cases a redeployed segment of the working intelligentsia tied to mass organization and popular service. When contradictions arise within the state—and they do—the terrain of struggle remains one where the popular classes have institutional footholds and ideological gravity.

Across many municipalities the pattern repeats. Mayors and local officials increasingly come from the social fabric of the communities they govern: educators, cooperative-organizers and local activists with roots in popular economy and community struggle. In 2022 the FSLN won all 153 municipalities in contests characterized by mass popular mobilisation. The trajectory of local officials echoes that of ministers: cadre emerging from education, health, cooperatives rather than oligarchic boardrooms. This is why the reactionary class hates municipal Sandinismo most of all. It is difficult to restore oligarchic rule when the local state does not answer to plantation owners or embassy clerks but to neighbourhoods, unions, women’s collectives and peasant assemblies that know their leaders personally and can mobilise in defence of them. Decentralised municipal governance in Nicaragua places elected local power in community hands. Reactionaries dream of a state that hovers above the people; Sandinismo has built a state that is tangled with them.

So when critics sneer that Nicaragua is a “one-party state,” they reveal only their own ideological shallowness. They mistake the consolidation of a class bloc for the suppression of pluralism. The truth is simpler: the popular classes have produced a governing apparatus with enough internal cohesion to defend sovereignty and carry out development, while the old ruling class has failed to produce a credible political alternative because it has no social majority to stand on. A ruling class that lost its mandate cries “authoritarianism”; a ruling class that keeps its mandate does not need to. The Sandinista state expresses the organized will of workers, peasants, and popular sectors who refuse to hand power back to the class that once treated them as tools. That is not dictatorship in the bourgeois sense. It is democracy in the Marxist sense: the self-organization of a people into a state that reflects their interests, their history, and their right to rule.

Every revolutionary process reaches the moment when persuasion is exhausted and the enemy reaches for the knife. In Nicaragua, that moment was 2018. What polite commentators in the North branded a “pro-democracy uprising” was, in material terms, a coordinated bid to break the popular bloc and retake the state. Opposition networks, backed by business, church, and foreign actors, escalated the confrontation through barricades, roadblocks, and armed actions that even multilateral observers acknowledged. The Truth Commission (CVJP) went further, documenting targeted killings, torture, kidnappings, arsons, and attacks carried out by opposition groups during the crisis. Foreign funding channels also played a role, as evidenced by publicly available U.S. democracy-promotion grants to Nicaraguan opposition organizations, while critical investigations such as Sefton’s “Nicaragua 2018: Uncensoring the Truth” traced coordination between local elites, media apparatuses, and external sponsors. Even NGOs critical of the government acknowledged the destabilizing nature of the crisis itself. This was not a spontaneous moral awakening—it was class war by other means. And once class war is launched against a popular process, the state cannot answer with poetry; it must defend itself or be destroyed.

The rupture with COSEP did not emerge from thin air. For a decade, the business elite tolerated the Sandinista government so long as they could shape policy and secure profits, a dynamic acknowledged even by establishment analysts and Brookings. But once the popular sectors consolidated real command—not only over elections, but over institutions, budgets, and development priorities—the alliance shattered. The oligarchy, unable to win at the ballot box and unwilling to accept a subordinate role, chose destabilization, a trajectory identified by critical observers NACLA. Washington, which has never accepted a sovereign Nicaragua, seized the opening to intensify pressure. Sanctions, including the NICA Act and RENACER, combined with an orchestrated media offensive and lawfare apparatus, functioned as instruments of hybrid war. The goal was regime change, not reform; dependency, not democracy.

Under these conditions, repression is not analyzed morally. It is analyzed structurally. A state confronted with a coordinated, externally backed destabilization campaign has only two strategic options: defend the process, or collapse into the fate of other nations targeted for regime change. Recent history offers the warning signs. In Chile, a democratic process was crushed and replaced with neoliberal terror under a U.S.-backed coup. In Honduras, a coup aligned with Washington paved the way for violent authoritarian rule and social disintegration. In Libya, foreign intervention destroyed a functioning state and unleashed national dismemberment. In Ukraine, foreign orchestration of the post-2014 transition was laid bare by the leaked Nuland–Pyatt call. Faced with these precedents, the Sandinista government chose survival.

The alternative would not have been Scandinavian pluralism. It would have looked like Nicaragua’s own neoliberal nightmare of the 1990s—mass privatizations, IMF tutelage, and the rollback of public systems—with familiar results: hunger, dispossession, and forced migration under capitalist “restoration.” And just as in 2018, Washington pursued regime-change pressure through sanctions, diplomatic coercion, and proxy instruments. Against such an offensive, the state cannot answer with poetry. When the choice is socialism or recolonization, survival is not only a right—it is a responsibility to the people who would pay the price of defeat.

The state that emerged from 2018 is more centralized, more disciplined, and less tolerant of enemy beachheads posing as “civil society.” This was not an accident. It was a strategic response to the recognition that hybrid war is not a season, but the new normal. When the empire finances your opposition, trains your NGOs, coordinates your media narrative, and writes your sanctions, pluralism becomes a battlefield, not a virtue. The popular classes learned through blood that their hold on power will be challenged again and again, and that only a state capable of closing its fist can defend the gains made by workers, peasants, and cooperatives. In this context, securitization is not the betrayal of democracy—it is the condition for its continuation.

The bourgeoisie calls this “dictatorship.” But from the standpoint of the oppressed, it is self-defense. Revolutions do not survive by allowing the old ruling class to conspire with foreign powers in the name of procedural niceties. They survive by recognizing the world as it is: violent, imperial, and governed by force. Nicaragua, surrounded by a hostile empire, cannot afford liberal fantasies. It can only afford clarity. And clarity demands that the state defend the social victories of the people with the same determination that the oligarchy defends its profits. That is the meaning of 2018. The fist did not close to silence the people. It closed to keep the people from being silenced forever.

Sanctuaries and Strikes: The Church, the Coup Plotters, and the State’s Counterstroke

One of the stranger ironies of 2018 was watching the altars turn into barricades and the pulpits transform into microphones for a rebellion that mixed legitimate anger from below with sabotage from above. Parts of the Catholic hierarchy—and some willing friends in the evangelical camp—opened their churches as sanctuaries, thundered against the state from the pulpit, and wrapped the opposition in a cloak of moral authority. In some moments, this saved lives and documented abuse in the chaos of street battles. But it also pulled the Church into the heart of an opposition bloc that sought not dialogue, but victory—political cover at home, and a megaphone abroad. The result was double-edged: a sanctuary for the wounded, and at the same time a political force helping to shape the narrative in the streets and in the headlines. The Church called this compassion; the oligarchy called it opportunity; and the empire, as always, called it useful.

The state responded by treating church-linked opposition networks as elements of a broader hybrid offensive. In 2023, the National Assembly revised the legal framework to permit denationalization of those deemed “traitors,” using measures such as Law 1145 and related provisions. That authority was then applied on a mass scale: 222 political prisoners were expelled to the United States and, shortly after, 94 more opponents were stripped of citizenship—with officials announcing that their properties would be seized—while broader counts put the total denaturalized at over 300. Officials presented these actions as legal self-protection; critics called them arbitrary punishment. The campaign unfolded amid sustained external pressure—U.S. sanctions and coercive statutes like the NICA Act and RENACER—designed to isolate the government. Under siege conditions, the state’s calculus was not liberal “pluralism,” but survival.

Western-based human rights bodies and some international monitors have denounced aspects of the crackdown — from arbitrary detentions to property seizures and the use of denaturalization as a political weapon. Those critiques are real and they must be recorded. At the same time, any left intervention that refuses to situate these events in the broader matrix of imperial coercion and domestic class struggle will be reduced to a sermon that does not help the people whose material stakes are at issue. We should condemn unlawful abuses and demand due process; we should also oppose sanctions and regime-change diplomacy that seek to reverse the accomplishments of popular organizing by any means necessary.

Finally: treason is a political category with consequences. Western “democracies” have incarcerated, exiled, and sometimes covertly eliminated those they judge traitors when their political objectives required it. That is not a programmatic endorsement of summary violence; it is a historical fact that the rules of politics change when foreign-backed forces seek to overturn a people’s hard-won gains. Our politics should demand legal clarity, public evidence, and proportionality — while standing unambiguously against foreign coercion, against the restoration of oligarchic rule, and for the right of the Nicaraguan popular classes to defend the project that they built.

The Right of the Poor to Govern

The entire quarrel over Nicaragua can be reduced to a single, irreconcilable question: do the poor have the right to rule, or must they always be governed by their betters? Everything else is camouflage. The oligarch calls it “authoritarianism” when his voice is no longer the voice of the nation. The empire calls it “tyranny” when a small country refuses to kneel. The NGO calls it “democratic backsliding” when foreign money can no longer shape domestic destiny. But beneath these slogans lies a simpler reality: the Sandinista process placed the hammer of state power into the calloused hands of workers, peasants, women of the popular economy, and patriotic cadres — and those who once ruled this country in their own image cannot forgive the crime.

A Marxist does not evaluate states by the adjectives they use to describe themselves, but by the classes they empower and the classes they suppress. In Nicaragua, the popular classes rose from the margins of history to become authors of their own future, organizing themselves into unions, cooperatives, neighborhood structures, and mass fronts capable of governing, defending, and transforming society. Opposing them is a comprador minority armed with foreign backing, nostalgic for a lost plantation, determined to restore a political order where sovereignty was a myth and the poor were a footnote. There is no “middle ground” between these projects. One must win. The other must lose. That is the law of class struggle.

2018 did not reveal the Sandinista government’s true nature; it revealed the true stakes. When the popular classes hold power, the reaction of capital, the clergy, and the empire is always the same: sabotage, sanctions, destabilization, and the manufacture of chaos. And when a revolutionary process defends itself, it is lectured about “democracy” by the same forces that toppled Mossadegh, strangled Allende, armed the Contras, and turned Libya into a graveyard. We owe these forces no moral legitimacy. The survival of a people is not negotiable, and the defense of sovereignty is not a crime. A revolution that refuses to fight for its life dies. A revolution that fights lives on — and evolves.

So let us be absolutely clear: Nicaragua today is a dictatorship only in the Marxist sense — a dictatorship of the popular classes, exercised against the oligarchy and against imperial domination. It is imperfect, contradictory, and unfinished, as all living revolutions are. But its trajectory, its social base, its class composition, and its enemies tell us exactly what side of the historical barricade it stands on. The task of the U.S. left is not to join the chorus of the empire, scolding a besieged nation from the comfort of imperial privilege. Our task is to oppose sanctions, expose regime change, reject NGO colonialism, and defend the right of the Nicaraguan people to build their future — without permission from Washington, Wall Street, or the Organization of American States.

The poor of Nicaragua have chosen their side. The oligarchy has chosen theirs. Empire has chosen its role. The only question that remains is what side we choose. History has already drawn the line. It is our duty to stand on the correct side of it, without apology, without illusion, and without fear.

https://libya360.wordpress.com/2025/10/ ... evolution/